Back when I was a professor in Political Science in the mid-1990s, I used to teach a course called “American Politics since 1930.” I remember how amazed students were at how much both the Democratic and Republican parties had changed. What is perhaps even more amazing is how much they have changed since the mid-1990s, especially the Democratic party.

I could have gone all the way back to 1776, but that would have left me unable to focus on recent politics. On Substack, I can go back as far as I want.

Today I will give a very broad overview of American politics since the Founding. I will focus on a few key areas:

Key elections that heralded major changes in the competitive balance between the two major parties.

Which party was the dominant party on the federal level

The policy preferences of the two major parties

The demographic groups who supported each party

It is not about class

Most people understand American politics as a clash of economic classes or a struggle between elites and the people. In some ways, they view American politics as a sort of a non-violent version of Karl Marx’s doctrine of class struggle. While there are some cases when this viewpoint is illuminating, it gives a misleading view of American political history.

Identity politics is nothing new

I often hear those on the Right complaining about identity politics, and in particular politics that assumes a zero-sum struggle based upon race, gender, or gender identity. They then make the claim that goes like “Identity politics is bad.”

The problem is that American politics has always been to some extent based on sub-national identities. The difference is that the identities have changed. And I doubt many of those conservatives would object to an ideology based on American patriotism, which is a form of national identity.

American political history has always been dominated by:

ethnicity

religion

region

Rather than a vertical struggle between classes, American politics was a horizontal struggle between people living in different sub-regions. Yes, local and regional elites were happy to present themselves as representing “the people,” but that was a rhetorical technique to win elections in their district.

I am going to divide American history into a number of what political scientists call “party systems” to show how ethnicity, religion, and region are far more helpful in understanding American politics than class.

Mega-trends in American political history

Before I start, I want to point out that American political history has been dominated by a few mega-trends:

The establishment of regional sub-cultures by the original immigrants from Britain, including:

Puritans immigrating from East Anglia to what is now New England.

Cavaliers immigrating from southwest England to what is now Virginia.

Quakers and other Protestant sects immigrating from northern England and Rhineland Germany to what is now eastern Pennsylvania.

Scotch-Irish immigrating from Lowland Scotland, the extreme north of England, and Northern Ireland to the Appalachian mountains.

Plantation owners from Barbados immigrating to what is now South Carolina.

The forced migration of African slaves into the Southeast.

The Westward movement of each of those cultures, essentially expanding their cultural domain to new states.

Subsequent waves of immigrants largely integrated into those regional sub-cultures, although the Irish, Germans in the Midwest, and the Mexicans in the Southwest were large enough in numbers to create new regional sub-cultures.

The continuing clustering of ethnic, religious, and racial groups in dense concentrations. Except for British Protestants and maybe Germans, no minorities span the entire nation in large numbers.

A constitution is almost entirely based on elected officials representing a very small geographical domain. The President is the only elected official who represents the entire nation.

Federalism, which gave each of these regional sub-cultures the ability to largely govern themselves (with the obvious exception of Blacks before 1965).

A two-party system that encouraged leaders of each sub-culture to form alliances of convenience with leaders of other sub-cultures to form governing coalitions on the federal level.

A weak federal government that gradually grew in power, particularly during the Civil War, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Great Society.

The reality of all this is that there was no elite that was running national affairs. The closest approximation of this was rich British Protestants who politically dominated the Northeast and finance and industries in New York City and Chicago. They were relatively powerful, but local and state elites in the South, Midwest, West, and rural areas banded together to resist this regional elite. And even in the big cities of the Northeast Irish politicians were more than able to hold their own.

Now let’s start our tour of American political history.

The Revolutionary era (1763-1787)

This period was not a party system because there were no political parties, but it played a sizeable role in determining all the above factors. The history of this period is dominated by squabbles between the five regional cultures and their gradual realization that they needed to figure out a way to work together to win independence from the British Empire and establish a viable Republic.

The first attempt, the Articles of Confederation, was a failure because it gave too little power to the federal government, and any one regional elite could veto all legislation. The Founder feared that this would lead to dissolution or foreign invasion by predatory European empires.

The second attempt resulted in the Constitution that we know today. It was an attempt to increase federal power just enough to enable effective self-rule, while still not enabling it to become a threat to newly won liberties.

Among its core concepts were:

Indirect election, particularly in the Senate and the Presidency. This enabled an educated elite to check the passion of the masses, which all the Founders were in favor of.

Federalism, which allowed the maximum amount of local self-governance while enabling the federal government to defend the nation and prevent restrictions on trade.

All federal elected officials, except the President, represent a small geographical area, which gave each locality representation in the federal government.

A balance between the power of the big states and the small states in the House and Senate.

A check on the growth of the power of the federal government by the Senate, which was elected by state legislatures. Note that this check no longer exists.

Separation of church and state. This enabled religious minorities, which all of them were, the right to worship without restrictions from the majority.

A Bill of Rights which restricted the power of the federal government to violate individual liberties. This was later extended to the states as well by Civil Rights legislation.

The reason why all these principles were baked into the Constitution is that all five regional minorities wanted to govern themselves and were terrified that a majority in Congress would destroy their liberties. Since they could not rule, they wanted to ensure that no one could rule over them.

The result has been an amazingly durable Constitution. While it is fashionable to focus on its limitations, the fact that it has endured almost unchanged for over 230 years is nothing short of extraordinary given all the changes that American society has undergone since then.

The First Party System (1792-1824)

The biggest mistake of the Founders, other than not finding a way to abolish slavery in all the territories instead of just the Northwest Territories, was not understanding the importance of political parties. This should not be surprising as there were no political parties anywhere in the world at the time, though Britain was increasingly dominated by the Whig faction and the Tory faction. In some ways, the Founding Fathers can be seen as Radical Whigs.

The Founders thought of political parties as dangerous factions that undermined enlightened individuals making decisions for the good of the nation. As should not surprise any modern observer, the nation split between George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton on one side and Thomas Jefferson and James Madison on the other side.

Eventually, this rivalry consolidated into the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. Note: some historians consider the Democratic-Republican party to be the first version of the subsequent Democratic party that was officially established in the 1830s.

The division was not based on class or elites versus people. It was based on the five sub-national cultures. The Puritans and Quakers supported the Federalists, while the other three cultures supported the Democratic-Republican parties. We can see this is the voting behavior of the 1800 Presidential election when Jefferson first won.

The dominant issues of the period were:

whether to ally with Britain or France in their many European wars

whether to support Alexander Hamilton’s policies promoting industrial development through tariffs and a financial system using the US bank.

Eventually, the Federalist party collapsed, and the “era of good feeling” essentially eliminated partisan conflict.

The Second Party System (1828-1860)

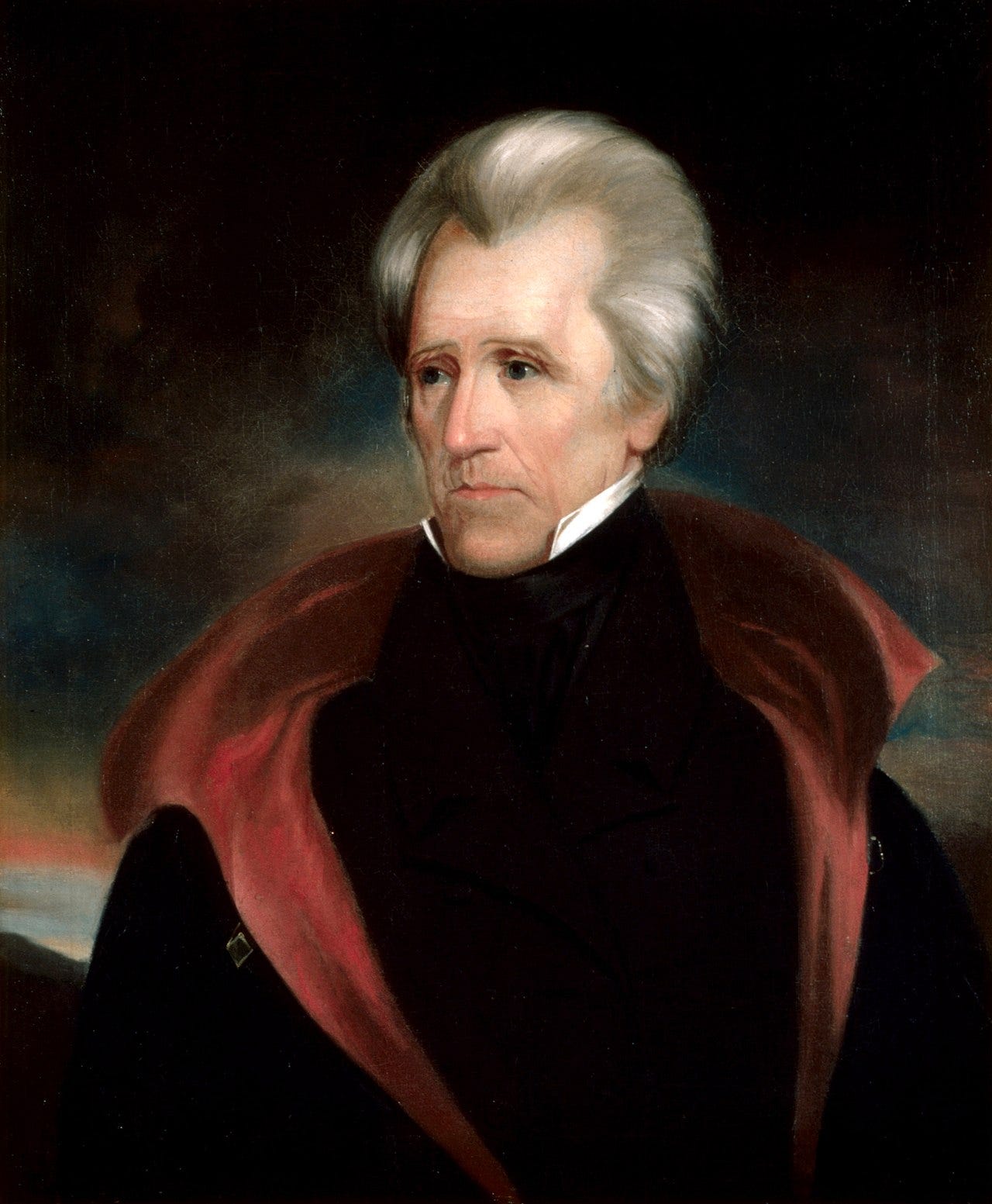

With the rise of the charismatic general Andrew Jackson, the sleepy era of good feeling was overcome by populist rhetoric. While I do not want to push the allegory too far, but Jackson strongly resembled Donald Trump. Andrew Jackson was the original American “populist” and he was famous for inviting crowds with muddy boots to trounce through the White House during the inauguration.

American politics quickly devolved into a pro-Jackson Democratic party and a ferociously anti-Jackson Whig party. The Whig party was essentially a rebirth of the old Federalist party, but it expanded the idea of industrial and financial development to include constructing a transportation system in Western states. But the core of the party was still in the urban Northeast, while the core of the Democratic party was in the South.

The core issues of the period were not class-based. They were:

Support or opposition to Andrew Jackson. Just as today’s Democrats believe Trump will abolish democracy, the Whigs thought Jackson would make himself king.

A related competition as to whether the Presidency or Congress should dominate the federal government.

The Whiggish American system, which was essentially an updated version of Alexander Hamilton’s policies.

Expansion of the powers of the federal government to implement the American system or the preservation of state rights.

Slavery (although mainly in the later half of the period)

During this period, a flood of Irish Catholic immigrants came to the Northeast and settled in the major cities. This horrified the Protestant Whig natives. The Irish defended themselves by joining the Democratic party and establishing urban political machines.

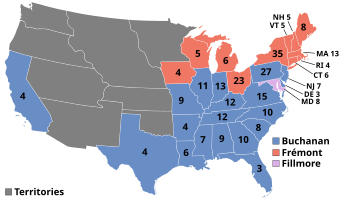

Ultimately, the Whigs failed to control the federal government, partly because its presidential candidates kept dying in office. The Democrats dominated this era, and their pro-slavery policies eventually led to the Civil War. By the 1850s the pro-slavery Southern Whigs and the anti-slavery Conscience Whigs were practically two separate parties who represented two different regional minorities.

The Third Party System (1860-1896)

Following the rise of the anti-slavery Republicans and the increasingly pro-slavery Democrats, the United States collapsed into Civil war. The period can be nicely split into two periods:

The Civil War and Reconstruction (1860-1876) where the Republican party dominated and forced the abolition of slavery and establishment of black political and civil rights by military occupation

A return to greater competitive balance (1876-1896)

The issues that divided the parties were very similar to the previous era:

The Republicans continued to support the American system, although often with less gusto. Tariffs were the biggest remaining issue.

Expansion of the powers of the federal government to implement the American system or the preservation of state rights.

Black rights (although almost entirely in the first half of the period). By 1876, the Republicans gave up trying to impose Black rights on Southern Democrats.

After 1890 silver versus gold coinage became a major issue, with the Democrats adopting the Populist pro-silver position.

In both periods, the Republican coalition included Protestant New Englanders, German Midwesterners, and Blacks (where they were allowed to vote). The Democrats were dominated by white Southerners and Irish Catholics. The establishment of Jim Crow laws after the end of military occupation and monolithic support of the Democratic party gave white southerners de facto home rule.

On the federal, however, the Democratic party rarely had governing majorities. Northern politics were primarily divided on religion (Protestant Republicans versus Irish Catholic Democrats), while Southern politics were overwhelmingly divided on race (white Democrats versus black Republicans whom rapidly lost their right to vote).

The Fourth Party System (1896-1932)

This party system was almost identical to the previous one. The biggest difference was the enormous wave of immigration from non-Irish Catholic nations which gave Irish urban machines more pliable voters. World War I and the Immigration Act of 1924 effectively ended mass immigration until 1970.

The Fifth Party System (1932-1968)

Here is where things start to get more interesting. The biggest changes were the Democrats becoming the dominant party on the federal level, and the Democratic coalition expanding to include trade unions, most of whose members were descendants of Catholic and Jewish immigrants.

The primary issues of the period were:

Whether to expand social insurance programs such as Social Security.

The degree to which the federal government should intervene in the economy. The parties largely flipped on this issue with the Democrats now favoring intervention and the Republicans abandoning their traditional support of the American system.

In the late 1940s and 50s, whether to form a multinational coalition against the Soviet Union and how much to spend on the military. This may surprise modern readers, but it was the Democrats who favored an aggressive foreign policy and increased military spending. Republicans had a large isolationist and small-government wing until the 1960s.

From 1948 to 1965 Civil rights and voting rights for blacks in the South. This may surprise modern readers, but this was not a partisan issue. Southern Democrats and Northern Democrats were the strongest on each side of the issue. Republicans were largely supportive of black rights, but they cared less than the Democrats on either side.

The Sixth Party system (1968-??)

Here is where things get very complicated and subject to interpretation. I am going to be writing much more on this time period, so I will be keeping it short here.

The 1966 midterm elections and the 1968 Presidential elections brought an end to Democratic dominance on the federal level, although they maintained sizable Congressional majorities. That did not end until the 1994 midterm elections, which one might claim, started our current era. One might also say that Democratic dominance on the federal level ended in 1980 with the election of Ronald Reagan and a government majority for the Conservative majority (Republicans plus moderate/conservative Southern Democrats).

But between 1968 and 1988, Republicans won five of six Presidential elections. Moderate and conservative Southern Democrats often worked with Republicans to create de facto conservative majorities in Congress.

Voting coalitions changed dramatically from the previous era. Now the Democratic coalition was composed of:

Young white, college-educated Baby Boomers

Blacks

Union members and other members of the white working class.

Starting in the 1990s, the children of Mexican immigrants began to become an important group of voters, but they are far less influential in leadership positions.

Over the period, the first group grew rapidly until it is now the dominant wing of the Democratic Party. Virtually the leadership positions, activists, campaign donors, and primary voters within the party are now controlled by the first two groups.

At the same time, the third group aged out or dropped out of the party. Many members of the white working class defected from the Democrats temporarily or permanently and supported George Wallace, Ronald Reagan, and Ross Perot. They are now very weak within the party and have little influence outside of a few Rust Belt states.

The Republican coalition largely consists of everyone else, though many of them are Independents who lean Republican in their voting behavior.

So when did the Sixth party system end? Or are we still living within it? Did the 1994 or 2008 herald a new party system? Is another realignment on the way?

I have no idea.

And I know that I am leaving out the entire 21st Century, but that will have to wait for another article.

Read more articles on American political history.

One important aspect that is frequently left out of these kind of histories is how the administrative positions worked.

Jackson instituted the so-called "spoils system" whereby most of the civilian administrators would be appointed by the president and replaced when the presidency changed.

Starting during the Fourth Party System this was replaced with a professional technocratic civil service

This bureaucracy was greatly expanded during the Fifth Party System by Wilson, FDR, and LBJ until it effectively has more power than the elected government.

Some further reading to your point about the distinct identities and cultures inherited from early British settlers: https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/04/27/book-review-albions-seed/