Can increased wind/solar retire Asian coal plants?

It seems unlikely, but fortunately there are other options...

Except for wood, coal is by far the worst violator of carbon emissions, air pollution, and human health. If Greens are to achieve anything like their stated goal of global Netzero in 2050, it will require a complete elimination of coal-burning plants throughout the world.

In previous articles I:

Argued that there is a better alternative to Green energy policies for both the economy and the natural environment.

Challenged Greens to give me one example of solar and wind fully replacing electricity from coal-burning power plant

Explained why Asian nations choose coal as their primary means to produce electricity

Argued that increased wind and solar are very unlikely to decommission American coal-burning power plants at scale

Explained why Greens should stop obsessing over carbon emissions in wealthy Western nations and instead shift their focus on coal-burning plants in China and the rest of Asia.

If you are skeptical about any of those points, I would recommend that you read the linked articles before proceeding to read this article.

This graphic (and the one at the top) depicts the problem that the Greens must confront. Quite simply, if you do not have a plan for Asian coal, then you do not have a plan for getting to Netzero by 2050!

Note that I focus on coal in this and other articles listed above, rather than other energy sources because:

Coal is the worst carbon emitter, except wood.

Replacing natural gas plants will do very little to reduce carbon emissions and air pollution, plus solar and wind need natural gas peaking plants to load balance.

Replacing nuclear plants with solar and wind makes no sense from either an economic or environmental perspective (even though Germany and Spain are trying to do it!).

Replacing hydro plants with solar and wind makes no sense from an economic and only it only makes sense from an environmental perspective if you value fish more than fighting climate change.

Replacing internal combustion engine transportation with solar and wind is impossible without radical new car designs or an extremely expensive deployment of grid-scale batteries (article on this upcoming).

See also my other posts on Energy:

Can increased wind/solar retire Asian coal plants?

This topic matters because East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia:

Is inhabited by more than half of the world’s population (more on this later).

The region is far more dependent on coal power than any other region.

Between 2000 and 2021 China built 81.6% of all new power plants constructed in the entire world. The vast majority of these were coal-burning.

And there is no sign that this trend will stop. As of July 2022, China has officially announced, pre-permitted, permitted, or is in the middle of construction of coal plants that will emit an estimated 44,000 million tons of carbon dioxide over their lifetime.

In 2023, Asia made up a full 53% of all global carbon emissions

Asian carbon dioxide emissions are expected to grow faster than any other region. It is very conceivable that carbon emissions in Asia will grow in greater absolute amounts than the total cuts in wealthy Western nations.

Since 1970, the region has experienced the fastest economic growth. Particularly since 2000, Chinese economic growth alone has led to a terraforming of:

The geographical distribution of carbon dioxide emissions

The location of global manufacturing

Global supply chains

Global capital flows

Availability and location of raw materials

Location of raw material processing (i.e. China went from being a non-player to being the dominant power in raw material processing)

Future economic growth within the next 20 years seems likely to be concentrated in:

South Asia (particularly India and Bangladesh)

Southeast Asia (particularly Vietnam and Indonesia)

The only mitigating factor is that Chinese economic growth is likely to be much slower (and perhaps even negative) in the next 20 years compared to the previous 20 years. This, however, is unlikely to decommission a large percentage of coal-burning power plants.

Solar and Wind are in the wrong places

In my previous article on the possibility of increased solar and wind fully replacing the electricity from coal-burning power plants in the United States, the problem comes down to:

Regions with high amounts of solar and wind energy are:

geographically limited and

typically distant from population centers.

Solar and wind do not produce electricity in anything like the times when demand for electricity requires it.

All technologies (grid-scale batteries and electrical transmission lines) that can overcome the above two problems are:

Very expensive at scale

Takes decades to construct

Have their own negative consequences on the natural environment.

The problem is much, much worse in East Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia because:

There are very few regions with either:

Large amounts of reliable solar energy

Consistent and strong onshore winds

Those few that have the above are very far from population centers, and they are all in China

The idea that China will construct a solar/wind-powered electrical grid that can support East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia is fanciful.

Geography trumps good intentions

First let’s take a look at a population density map of China, which is by far the largest consumer of coal in the world.

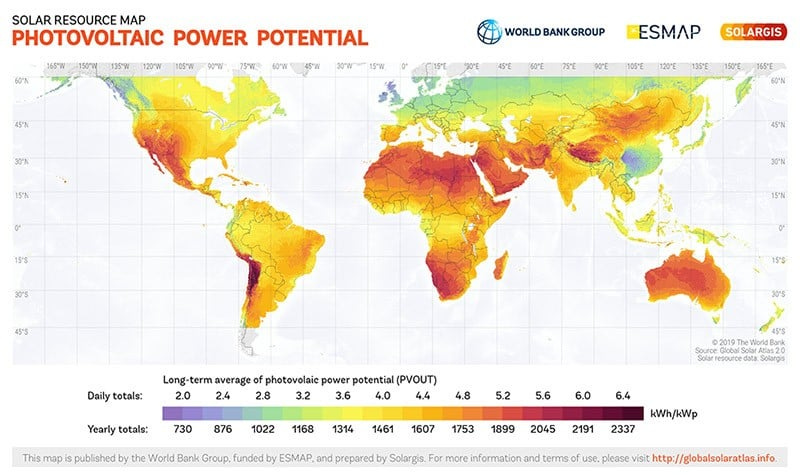

Now let’s take a look at solar radiation on a global scale. Dark red areas have large amounts of potential solar energy. Notice, that most of East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia is either blue, green, yellow, or light orange. The two biggest exceptions are the southern edge of the Himalayas (by far the least accessible geographical area in China) and the Gobi desert.

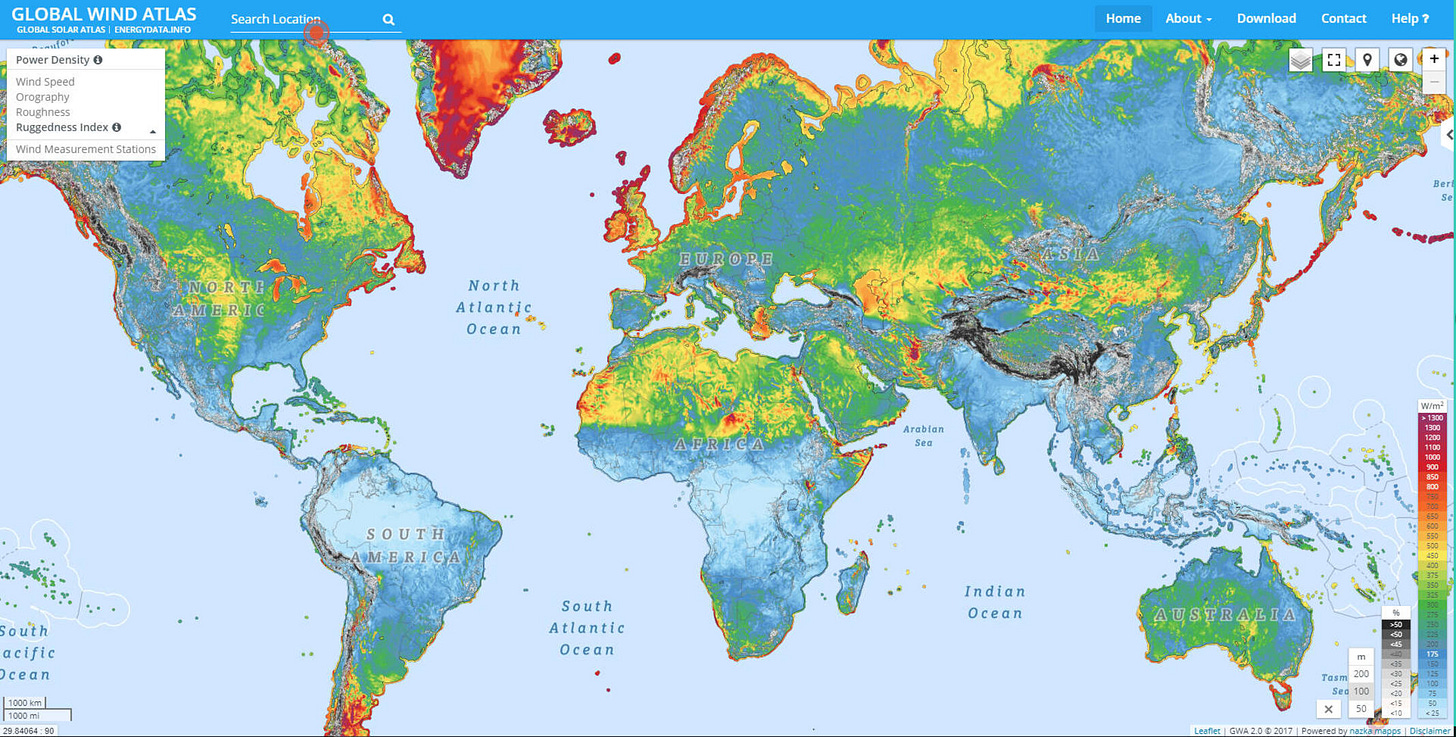

Unfortunately, the global wind map looks even worse for East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Except for scattered regions in the Gobi desert in China, there are basically no onshore locations with steady and strong wind resources:

Now let’s take a look at a zoomed-in view of Asia:

I don’t notice much yellow, orange, or red. As with solar, there is some wind resources in the Gobi desert, but this is not where the population is concentrated. The vast majority is blue.

Now let’s take a look at a zoomed-in view of solar resources in China. Note that all the densely populated areas within China have very low or extremely low levels of solar radiation. In fact, southeastern China may be the single worst area for solar power in the entire world. Meanwhile, central-eastern China is also below the world average.

Given the distance and huge mountain range in the Himalayas, the Gobi desert that borders Mongolia is the only cost-effective site for solar installations. While some portions of this region are within a few hundred kilometers of Beijing, the vast majority of Chinese cities are thousands of kilometers from solar regions.

Can technology trump geography?

Now it is technologically possible to install vast electrical lines to connect to all the major cities, but it will be extremely expensive and each additional kilometer in cabling loses a greater percentage of electricity.

Geography alone puts a serious upper bound on Chinese solar power.

Can giga-watts of electricity be produced in the Gobi desert as well as connecting electrical lines? Yes, and the Chinese are doing it now.

Can that electricity make it possible to decommission Chinese coal plants at scale? No, not without an additional massive investment in utility-scale batteries.

So realistically, to make a real dent in Chinese coal plants, the Chinese government needs to construct:

A massive set of solar installations in the Gobi desert

A massive network of electrical lines connecting each solar installation to a hub.

A massive network of electrical lines running from the hub to each city in China (many of which are 2000+ km miles away).

A massive network of utility-scale batteries (at one end or both of the electrical lines) to store power for night-time.

I will assume that China already has an electrical grid within each metro area to distribute that electricity.

What about the other 6 months per year?

And note that the massive investments that I mention above only produce a viable amount of electricity for about 6 months each year (summer, late spring, and early fall). Since the Gobi desert is relatively far north, the region will generate far more electricity in the summer than in the winter, so it is not clear that solar power is even a four-season solution with all of this infrastructure.

The significance of Chinese solar installations

There is absolutely no doubt that the Chinese government has undertaken a massive project to build up solar and wind resources in the Gobi desert. The question that we need to ask ourselves is:

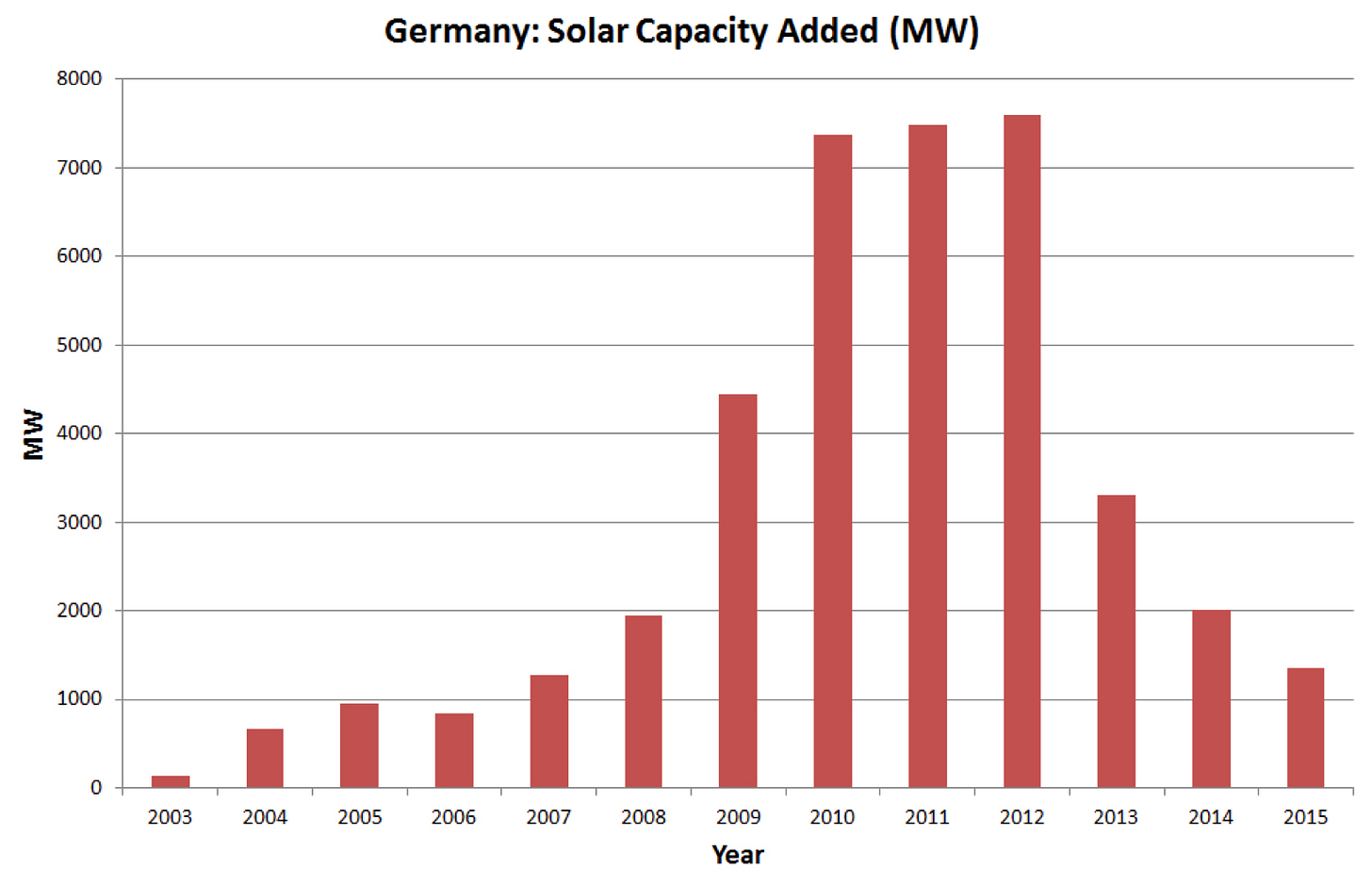

Is this a temporary spurt in domestic production like we saw in Germany and other European nations (due to starting and ending of subsidies), or

Is this the beginning of a massive shift in Chinese energy production that leads to a phasing out of coal?

Typically what happens is that a national government gets very excited about “cheap” solar and then passes massive subsidies and mandates to start construction. Then a few years later, that same government realizes that:

The increase in solar production is not generating enough electricity to phase out fossil fuels

Increased intermittent electricity is causing serious problems for the stability and cost of the grid

Electricity prices are skyrocketing, causing political problems.

The subsidies are not financially sustainable.

The result is that the government phases out or significantly decreases subsidies, so new construction crashes. We have seen this pattern repeat itself in many nations.

Is this real construction?

Given the recentness of this massive Chinese solar build-up, I have my doubts about the long-term sustainability of this program. First of all is the cycle that I mentioned above. Second, similar cycles of production subsidies have been a key part of the Chinese economy for the last 20 years.

The Chinese economy has been a continuing cycle of debt-financed infrastructure projects. The type of infrastructure is constantly shifting, but the overall strategy remains the same. We have seen this investment cycle in high-speed rail, housing, and other sectors.

To be more specific, Communist China has gone through a repeating cycle of:

The Chinese central government encourages local governments to build massive amounts of infrastructure through regulations and subsidies (often via government-controlled banks).

Local governments go crazy with a massive number of infrastructure projects

The World is impressed, and so are the Chinese people.

The central government wants to keep everyone impressed, so it does not listen to internal experts who are worried about signs of over-building.

Continued subsidies cause local governments to construct way beyond the needs of the people.

The initial benefits of increased production lead to diminishing returns for the Chinese economy.

Finally, central government shifts to a new type of infrastructure to promote.

Local governments stop offering subsidies.

Construction collapses and empty infrastructure sits dormant. The debt is still left over for future generations.

The cycle continues in another domain.

Can we be so sure that the same thing is not happening with solar and wind?

While I am sure that some amount of useful electricity will come out of these projects, I am also waiting for China to get to step #7 above. I think the geographical limitations will be too difficult to overcome with any amount of investment.

What about the rest of Asia?

So far, I focused mainly on China because they are the largest Asian economy and the one with the most coal plants. Now let’s briefly focus on the rest of Asia with over one-quarter of the world’s population. India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and other Asian nations are rapidly constructing coal-burning power plants. All those nations have:

No regions with plentiful solar radiation

No regions with strong and steady onshore wind

An antagonistic or at best neutral relations with Communist China.

Given all the above it is inconceivable that the rest of Asia will increase solar and wind production at levels enough to phase out coal-burning power plants. Most likely, they will continue to increase coal consumption.

And the idea that China will build up a solar/wind-based electrical grid to share its electricity with the rest of Asia in the near-term is laughable. Forget the cost, just the geography, demography, and geo-politics make this near impossible.

Just one example of the problem: Gansu wind farm

After writing this article, I ran across a great video that illustrates the problem of replacing Asian coal with wind and solar. It is about the largest Gansu Wind Farm in the Gobi Desert. Its total capacity is a colossal 20 GW, making it by far the largest wind farm in the entire world. In fact, the Gansu Wind Farm surpasses the total capacity of wind production for all but 8 other nations in the world.

The maker of this video is obviously very supportive of the project, but if you look at the numbers, it is not at all clear that the project will lower Chinese coal usage.

A few key negatives mentioned in the video:

The wind farm is larger than the size of Belgium!

The wind farm is very far from urban areas that need the electricity.

The electricity produced is almost double the cost of electricity produced by coal, so there is no economic incentive to purchase it (7.5 cents per kWh versus 4.2 cents).

About 40-50% of the electricity being produced by the project is not used due to the lack of transmission cables to the urban areas (which are huge projects unto themselves).

Assuming a capacity factor of 30% (which is optimistic), this colossal project produces as much electricity as about six large coal plants. China has 1142 coal plants in total.

So even with the most optimistic assumptions, the project can decommission roughly 0.5 percent of Chinese coal plants. And remember, this is by far the biggest wind farm ever constructed.It is not clear whether the project includes utility-scale batteries, but to replace one coal plant, they would need to be massive. A 1GW coal plant generates roughly 20-24 GWh of capacity. This would be roughly 8 times larger than the biggest energy storage system in the world.

Based on the above, it is safe to assume that the bulk of the electricity being generated by the Gansu Wind Farm will be in addition to coal, not instead of coal. And I am skeptical any nation but China will pull off such a large renewable project within the next few decades.

The Verdict

So the idea that Asia can ramp up solar and wind to phase out their coal-burning power plants by 2050 is Science Fiction. Yes, they can produce electricity from solar and wind, but it will be in addition to coal, not instead of coal.

There is another option

Fortunately, there is another option that is both good for the economy and good for mitigating damage to the natural environment. We can replace coal-burning power plants with a blend of natural gas, nuclear, and hydro. The exact blend will vary by geography and local cost structure. And the United States can help make it happen, but not through Green energy policies.

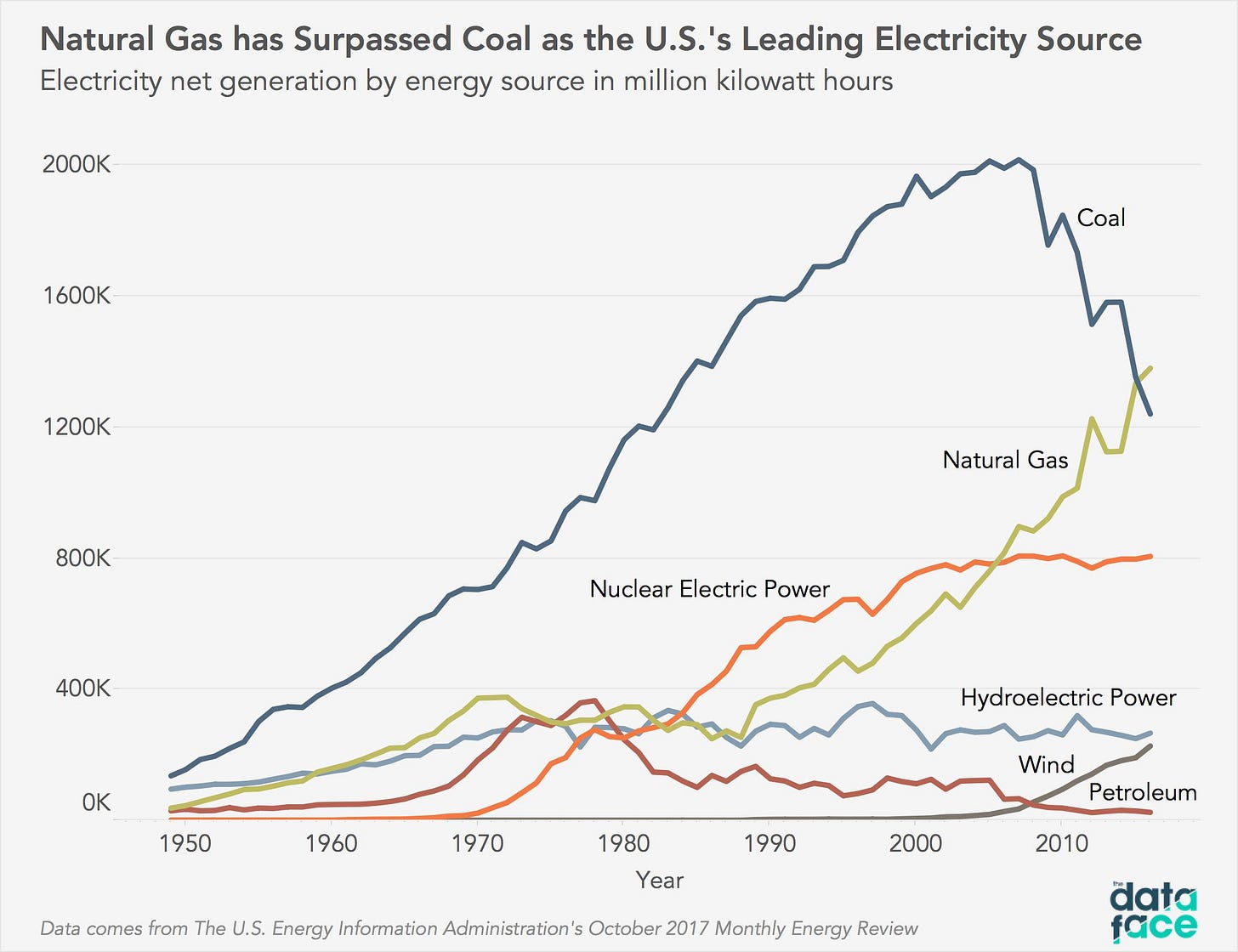

In the United States, natural gas is by far the most cost-effective option. This is exactly why it has been decommissioning coal-burning power plants in the United States over the last 20 years. With a strong push, we could complete the job in only 5 years. After that, the United States can help the rest of the world make the same transition.

See also my other posts on Energy:

Anyone who falls for climate emergency, overabundance of CO2 or NetZero bullshit with “renewables” as a viable option needs a rectocranial eversion surgery.

Why are you pushing for a coal tax instead of a simpler carbon tax? Governments and businesses the best way to reduce their carbon emissions. I don't really care about how they go about doing this.