The term “The Top 1%” is not used as often as it was around the year 2010. Typically, when people refer to the Top 1%, they mean:

the top 1% in any given year based on income or

the top 1% in any given year based on wealth.

The connotation of this term is that there is a small, exclusive group whose political influence is far greater than regular voters.

I think that it is absolutely true that a relatively small group of people have an inordinate amount of political influence, but their influence is not based on income or wealth.

Their real source of their political influence comes from their political activism. Most people, regardless of their income or wealth, do not participate in politics very much. The vast majority of people vote in general elections and occasionally discuss politics but rarely go beyond that level of political activity.

The real influence comes from those who vote in party primaries for federal, state, and local positions. This group is:

surprisingly small as a portion of the total population, and

it is extremely unrepresentative of the ideological beliefs of the rest of the population.

Now, you might think that the total number of these primary voters is far more than 1% of the population, but bear with me. Once you really analyze the numbers, you see how few people really matter in American politics.

Below is a map that is useful for this exercise. It is the 2023 Cook Political Report Partisan Voting Index (PVI) that uses general election results from the 2020 and 2016 Presidential elections to create a single number that represents the partisan tilt of each US House district (typically between D+20 (the district is 20 percentage points more Democratic that the average for the rest of the nation) and R+20 (the district is 20 percentage points more Republican).

Let’s start with a few observations:

There are only two parties with a realistic chance of winning an election: the Democratic party and the Republican party.

With the exception of the Presidency, all elected officials represent a very narrow geographical area. Even the Governors and Senators of California, the most populous state in the Union, only represent about 10% of the total US population. The vast majority of elected officials represent far less than 1% of the total US population.

Democratic and Republican voters are highly differentiated by geography. This means that virtually no states or electoral districts are representative of the entire United States. The vast majority of electoral districts are very different from the national average.

Despite low voter approval of Congress, incumbents are regularly elected 95% of the time. Voluntary retirement is the most likely reason for an incumbent not to be reelected. In the US Senate, the incumbent reelection rates are over 80%.

US House reelection rates; Source The vast majority of general elections are uncompetitive, so we know which party will very likely win long before the candidates are even selected.

In the US House, for example, about 87% of general elections are won by a 10% margin or more. The average margin of victory in the US House general elections in 2020 was 28.8%, and it was 18.1% in the US Senate. This leaves roughly 60-80 competitive US House elections each year at most.

State and local elections are typically even less competitive. And those uncompetitive seats are stable over time.The nominees of each major political party are elected by primaries.

Because of the above two factors, it is the primary of the majority party in the district that is the “real” election. In 85+% of elections, the general election is a foregone conclusion. Whoever wins the primary of the majority party almost inevitably wins the general election.

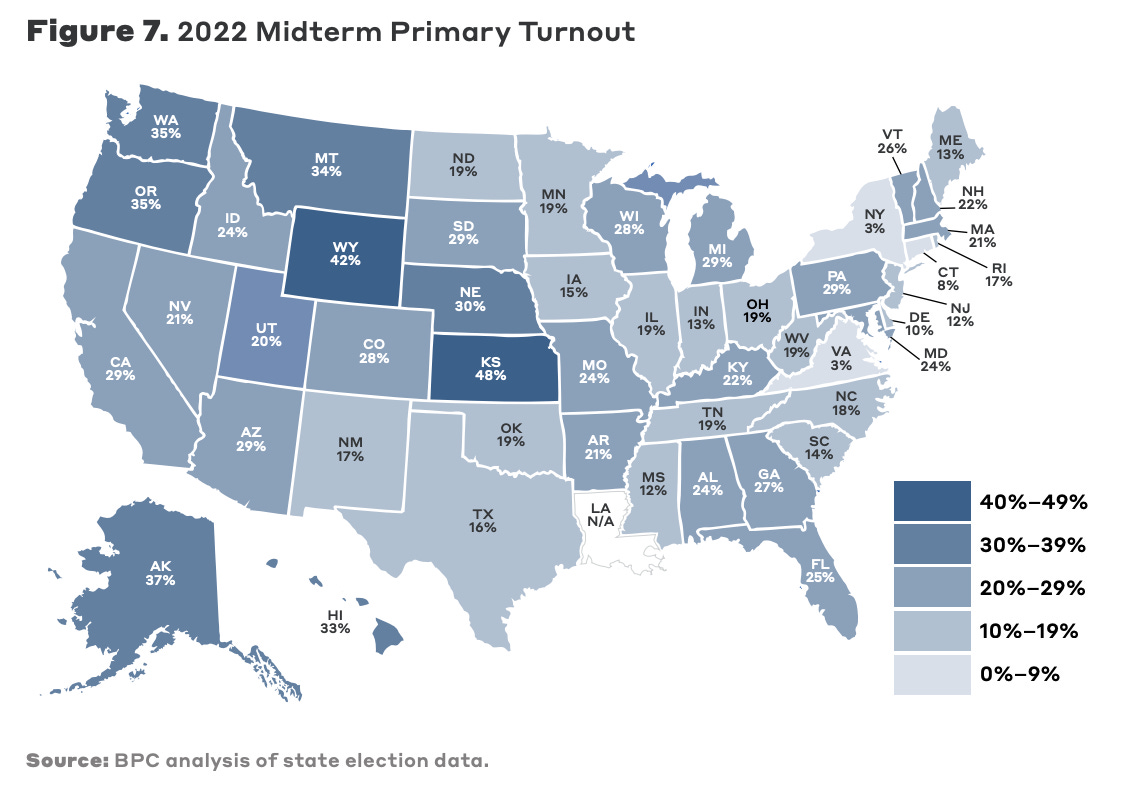

Turnout in primaries, with the exception of Presidential primaries, is extremely low. Single-digit percentages of the adult population are the norm.

Note: official turnout percentages are very deceptive as they are measured as a percentage of registered voters, not as a percentage of the total adult population.In 169 of 380 safe US House seats had only one candidate on the ballot (almost always the incumbent). This leaves 100 million voters without a meaningful choice.

In 22 states, only registered party members are allowed to vote in party primaries. This excludes 23 million registered Independents and another 4 million minor party voters.

Registered voters of the minority party in the district are either excluded or choose not to participate because they have not candidate to support.

Voters in party primaries have more extreme ideological views than:

the American people.

typical voters in their district

even typical party voters within their district.

The above is particularly true for primary voters in the majority party.

In other words, Democratic primary voters in San Francisco are extremely unrepresentative even of other Democratic voters throughout the nation. Republican primary voters in rural Wyoming are extremely unrepresentative even of other Republican voters throughout the nation.Competitive primaries within the majority party are often have three or more viable candidates because they offer easy access to the corridors of power. This means that the victor of competitive primaries for the majority party often wins far less than 50% of the vote.

Within both Congress and state legislatures, 80+% of the seats are controlled by elected officials from uncompetitive districts, where they only have to worry about being “primaried” by ideological activists within their own party. For this reason, again except for Presidential general elections, both parties can ignore 60+% of the ideological spectrum (moderates and voters of the opposing party).

Those same elected officials from uncompetitive districts are free to select legislative leaders and party leaders without input from the opposition party and moderates within their own party. With the exception of the Speaker of the House, these leaders are elected by majorities within the majority party.

Elected officials in competitive districts have an incentive to “run towards the middle” in order to win the general election, but they are also the most likely to lose in subsequent general elections. This means that moderates with both major parties are always more vulnerable to “Tide” elections favoring the other party than party stalwarts. This keeps elected officials from uncompetitive districts solidly in control of their party.

So the real question is: What is the size of the electoral majority (i.e. 51%) for the major party primaries in uncompetitive districts which make up 80% of the districts?

That works out to about 1% of the US population:

0.5% of all adults are Democratic primary voters in Democratic-dominated districts (this makes up about 40% of the total number of districts or a little under 80% of the seats that Democrats need to achieve a governing majority in the US House).

0.5% of all adults are Republican primary voters in Republican-dominated districts (this makes up about 40% of the total number of districts or a little under 80% f the seats that Republicans need to achieve a governing majority in the US House).

Let’s go through the numbers, and see how I came to that number.

If you are interested in this article, you might want to read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See my other articles on Electoral Reform:

The calculation

Primary election turnout

The key metric is turnout in the primary of the majority party in competitive districts, not overall turnout. It may seem easy to determine US House primary election turnout in uncompetitive districts, but unfortunately, it is not.

Official US House primary election turnout is roughly 20%:

This figure ignores that the Democratic and Republican primaries are effectively separate elections with differing voters. This cuts the actual turnout down to roughly 10%:

The official turnout percentage varies greatly by geography. In general, competitive seats have far higher turnout than the 80+% of uncompetitive districts:

Official data greatly overstates actual turnout, because:

It is typically calculated as a percentage of registered voters, not total adults or voting-eligible population (VEP).

Official primary election turnout data does not differentiate between:

Primary election turnout in competitive districts (which is much higher than the average).

Primary election turnout in Democratic primaries for Safe Democratic districts (which is 50% of the key metric). In those districts, the turnout for the Republican party primary is irrelevant.

Primary election turnout in Republican primaries for Safe Republican districts (which is the other 50% of the key metric). In those districts, the turnout for the Democratic party primary is irrelevant.

Because of the above, there is no one good data point that tells us:

The percentage of American adults who vote in Democratic primaries in Safe Democratic districts.

The percentage of American adults who vote in Republican primaries in Safe Republican districts.

A few years ago, I calculated a ballpark figure based on official data, but unfortunately, I cannot find the source of the raw data that I based my estimate on.

My estimate is that:2.5% of the total adult population within the district vote in Democratic primaries in Safe Democratic districts.

2.5% of the total adult population within the district vote in Republican primaries in Safe Republican districts.

Democrats

Roughly 40% of the House (or 180 seats) is composed of Democrats elected from safe Democratic districts. Exact numbers vary between elections.

In those seats the general election does not matter, because the Democratic nominee will virtually always win.

In those seats the Republican primary does not matter for the same reason.

To win 51% of the vote in those Democratic primaries in those districts requires:

1.28% of the district’s adult population, or

0.52% of the nation’s adult population.

Note that turnout is higher in the rare competitive primaries for the majority party when the incumbent retires, but this tends to attract many candidates, so less than 51% of the vote typically wins. So higher turnout does not actually increase the total number of votes needed by much.

This means that those 180 seats will be selected by roughly 0.52% of the nation’s adult population. The representatives elected from those 180 seats will always control the Democratic party, and particularly its leadership and most experienced members.

Republicans

Roughly 40% of the House (or 180 seats) is composed of Republicans elected from safe Republican districts.

In those seats the general election does not matter, because the Republican nominee will virtually always win.

In those seats the Democratic primary does not matter for the same reason.

To win 51% of the vote in Republican primaries in those districts requires:

1.28% of the district’s adult population or

0.52% of the nation’s adult population.

This means that those 180 seats will be selected by roughly 0.52% of the nation’s adult population. The representatives elected from those 180 seats will always control the Republican party, and particularly its leadership and most experienced members.

The Grand Total

So combined together, 1.04% of the adult population is choosing 80% of the US House seats. The other 98.96% of adult Americans have little or no impact on that outcome.

Do those 1% really control Congress?

No, that is an exaggeration, but not by much.

It is more accurate to say that:

40% of Representatives from uncompetitive districts control the Democratic party within the US House. That 40% is chosen by roughly 0.52% of the nation’s adult population. Democrats in Congress can largely ignore the other 99% of American adults unless they suddenly show up in the primaries.

40% of Representatives from uncompetitive districts control the Republican party within the US House. That 40% is chosen by roughly 0.52% of the nation’s adult population. Republicans in Congress can largely ignore the other 99% of American adults unless they suddenly show up in the primaries.

The other 98.96% of adult Americans are excluded because of one or more of the following reasons:

They are not registered to vote.

They do not live in the “right” district

They are not allowed to vote in a closed primary because they are either:

Registered to the minority party

Registered Independent

Registered to a minor party.

They, for whatever reason, choose not to vote in party primaries.

The rest of the voters have very little influence on the US House unless they happen to be voters in swing districts (which is less than 15% of the total population).

Swing seats

Now, of course, there are still another 10-20% of US House seats that are competitive enough that either party can sometimes win the general election. The outcome of 60-80 seats almost always determines which party controls the US House.

Realistically, the actual number of competitive seats is far smaller in each individual election. In a “Blue Tide” election where the electorate is swinging toward the Democrats, most districts that lean Democratic will not be competitive. The same goes for districts that lean Republican in “Red Tide” elections.

These Swing seats will tend to have:

Competitive general elections in most years. Off-year general election turnout is roughly 37.8%.

This means that the winning coalition in swing districts is roughly 19.3% of all adults. This is almost twenty times the level of turnout as in typical primaries in non-competitive seats.

Realistically, the incumbent Representative will face little or no competitive within their party primary unless they did something that really angered party primary voters.

The party primary to select a challenger will likely be quite competitive and turnout will be much higher, but still nowhere near 10% of the adult population

Because of the above, most candidates in competitive swing districts will have an incentive to “run toward the Center” in the general election campaign. The problem is that the winner of these competitive elections:

Is very likely to be relatively inexperienced (because competitiveness leads to short careers) and

Is very likely to have little influence within the party.

Will be very vulnerable to defeat in the next election.

Will be very unlikely to have a long enough House career to reach Congressional leadership or committee leadership positions.

Will be under tremendous pressure from party Whips to vote the party line regardless of campaign promises.

But what about rich donors?

I am sure that many people are wondering: “But what about rich donors? Are they not the really influential people in American politics? Why do you ignore them?”

Yes, rich donors who make very large financial donations to the parties and candidates are very influential, but I would argue that they are a subset of the Top 1%. A very significant amount of campaign funding comes from small donors. And those small donors are exactly the same people who vote in primaries (although many of them will be from out of district).

I see no evidence that campaign donors are divergent in their ideological views from activists who turn out in primaries. At most, they are just “more of the same.” They might be able to push one specific issue, but if that issue really conflicts with what primary voters believe, their candidate will not win.

Quite simply, if a candidate cannot get the support of primary voters, it does not matter what mega donors think. Yes, large campaign donations enable a candidate to run a viable primary campaign, particularly when running for President, but their ability to appeal to primary voters is a fundamental precondition for political success.

American politics is littered with candidates who had huge amounts of money but failed miserably in party primaries. And American politics is littered with candidates who ran on shoe-string budgets raised from small donors but galvanized party primary voters.

Ideally, a candidate has both, but primary voters are more important than campaign donors.

In fact, a critical factor enabling a candidate to convince big donors is showing that they have the ability to win the primary. New candidates typically have to get by on small donations and enthusiastic activists until they have proven their viability to the large donors. Then the big donations can come in. So the big donors tend to reinforce the preferences of party primary voters.

For very expensive campaigns like for the President, Senators, and Governors of populous states, large donors become much more important. These races, however, are typically dominated by candidates who have already proven themselves in lower offices, so they have already proven themselves with party primary voters and small donors. In these higher-profile campaigns, big donors are typically looking to support the candidate from their favored party who they think can win. That means big donors care what primary voters think. It is only in competitive general elections that primary voters become less important.

Some exceptions to the rule

Now, I want to stress that there are important exceptions where the Top 1% has far less influence over election outcomes:

Presidential general elections are very different.

And, of course, the President has a great deal of power, particularly in foreign affairs. Presidential general elections are:national in scope,

attract huge amounts of media coverage

have far higher turnout and

are typically competitive.

Presidential primaries where the party does not have an incumbent are also far more competitive, but realistically a relatively small number of early state primaries filter down the number of candidates very quickly. Those states include Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and maybe a few other states.

Turnout in those states is significantly higher than in other primaries, but people living in other states with far less influence on the outcome, so turnout declines quickly.Senate and Gubernatorial elections in competitive Purple states also fit those characteristics, and the winner of those elections in any given year may gain a majority in the US Senate. But the party majority and the party leadership will be overwhelmingly composed of party stalwarts from uncompetitive states.

Moderates will be forced to conform to the dictates of the party to have a viable political career. Just look at what happened to Joe Manchin and Krysten Sinema. They were harassed relentlessly until they left the party.

Governors are a little different as they can set their own agenda and potentially push legislation that their party would not otherwise support. It is not a coincidence that many of the most talented and moderate politicians have been Purple state governors.About 20% of US House districts are fairly competitive, and the winner of those will gain a majority in the US House. Those elected in those districts will suffer from the same constraints as I listed above.

In general, state and local elections are far less competitive and have lower turnout than federal elections. Some are officially non-partisan.

While these competitive high-profile Presidential and Purple state governor/senate elections receive the lion’s share of media attention, it is important to note that they are only a tiny percentage of the total number of elections. Uncompetitive elections dominated by party primary voters are far more common. I would argue that the collected power of the offices that are heavily influenced by party primary voters is far more than the list above.

Do you have a better electoral system?

Yes, I do. Thank you for asking.

No electoral system is perfect, but I think the reform proposal outlined this article is far superior to what we have now. And this article explains how we can get this done.

If you are interested in this article, you might want to read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See my other articles on Electoral Reform:

Bravo! I teach public choice economics at the University of Virginia, Wise campus. We spend a week thinking about voting and and its foibles. Rank-order, instant-run-off voting is staunchly resisted by both political parties. Why? You and I know why; it's because the primary system keeps power where the politicians want it.

Will any reform overthrow Michels’ Iron Law of Oligarchy? That is doubtful. Also, reform doesn’t mean we will get good ideas. Libertarianism seems to be the better long-term solution rather than romantic ideas about democracy.