Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

And why they did not generate progress

Agrarian societies are a type of society that produces the majority of its calories from either:

Farming domesticated plants (using animal-driven iron plows) and

Raising domesticated animals.

Because of the unique character of these types of food and the production techniques used for them, Agrarian societies were very different from other types of societies. Agrarian societies differed from earlier Horticultural societies which farmed using far less efficient hand tools. This difference does not seem important, but the long-term impact on those societies was profound.

Agrarian societies dominated recorded history from 3000 BCE until modern times. Pretty much every pre-industrial society that you read about in history books falls into this category. Famous examples of Agrarian societies include the Babylonians, Sumerians, Persians, Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, Greeks, Romans, Spanish, Portuguese, Germans, and Russians.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my other articles on Society Types and related topics:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Agrarian societies (this article)

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)

Take a look at the above graphic, which I explain in greater detail here.

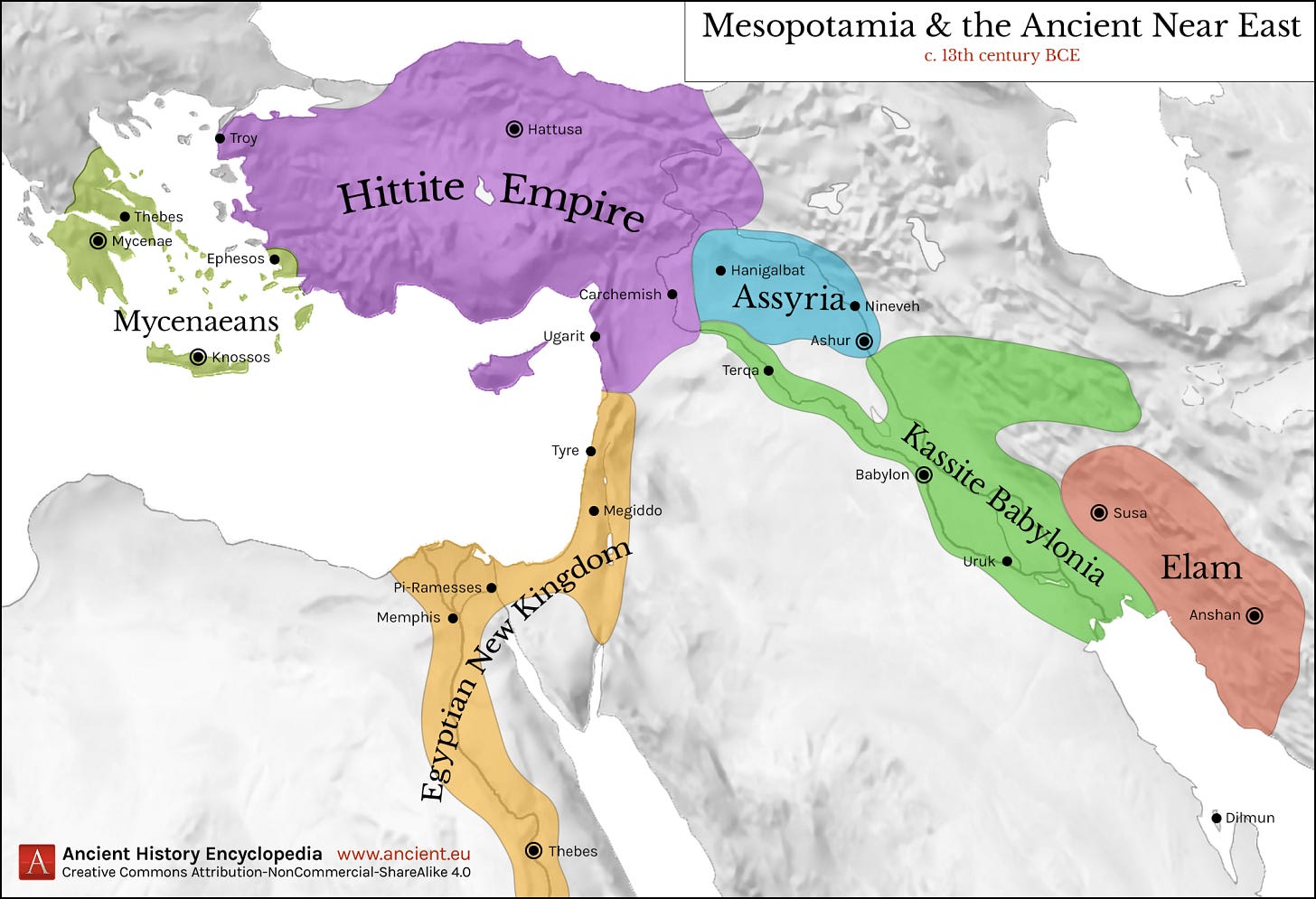

Agrarian societies evolved out of Horticultural societies sometime around 3000 BCE in the Tigrus-Euphrates river valley. Inhabitants of local Horticultural societies gradually learned how to invent new technologies and processes that increased the productivity of land and individual farming families. This increased food surpluses, which in turn had a cascading effect on the rest of society.

Among the most important innovations that enabled the establishment and spread of Agrarian societies were:

Animal-driven traction plow (typically pulled by oxen, water buffalo, or later horses)

Irrigation that spreads river water to a much wider area

Alphabet and numeric systems that enable scribes to keep track of taxes and document law.

Cities (which I am loosely defining as villages that grow to a population of over 10,000 inhabitants)

Military organizations (i.e. organized armies full of conscripted soldiers or mercenaries)

Extractive institution (which focused on extracting the food surplus from farmers and dispersing them to centralized political, military, and religious organizations that were dominated by elites that owned most of the land)

Soon after the food production technologies diffused to the Nile River valley, so Ancient Egypt came to resemble the Agrarian regimes of the Tigrus-Euphrates river valley

As the population increased in Horticultural societies, humans were under constant pressure to innovate more efficient means of producing, preserving, storing, and distributing food. In a few major river valleys around 3000 BCE, animal-driven scratch plows evolved that increased agricultural productivity far beyond the level possible with simple hand tools.

By substituting more powerful animals (usually horses, oxen, or water buffalo) for human muscle power, these societies created far larger food surpluses. At first, these societies were dependent upon irrigation to grow crops, but some farmers learned how to use plows in more arid regions. This key enabling technology gave birth to Agrarian societies in the Middle East and later throughout much of Eurasia.

Agrarian societies dominated recorded history up until the 19th Century. Such societies, including the Babylonians, Sumerians, Hittites, Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, Indians, Greeks, Macedonians, Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Ottomans, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Germans and Russians almost exclusively monopolize our pre-modern history books.

These Agrarian societies produced large cities, powerful armies, sprawling empires, impressive architecture, beautiful art, compelling religions, and most of all a written record of all of these achievements. Sadly, though, Agrarian societies did relatively little to benefit the vast bulk of their inhabitants.

Key technologies enabled Agrarian societies to do the following:

Dramatically increase the productivity of their agriculture (using draft animals to pull iron plows)

Store information and communicate at long distances (using the alphabet, numerals, writing, and printing)

Extract the food surplus from peasants (using centralized extractive institutions)

Wage war against other societies (using armies and navies equipped with iron weapons and armor and later gunpowder)

While Agrarian societies had a vast number of cultural differences, they had many common characteristics. Most importantly, they produced the majority of their food calories from animal-driven plows. The plows evolved over time. Starting from simple scratch plows that used a wooden post to just scratch the surface of the soil, iron shares were gradually adopted. This gave the plow far greater strength to break tougher soil, expanding the area that could be cropped.

The animals used to pull the plow also varied. East and South Asia generally used water buffalo, while the Mediterranean and Europeans used oxen and later horses. Both are pathetically slow and weak compared to modern tractors, but compared to hand hoeing, they were a huge time-saver. By plowing land faster, peasants could then work larger plots of land, leading to greater grain production and more mouths to feed.

All Agrarian societies relied predominantly on one staple food: the Middle East, Mediterranean, and Europe relied mainly on wheat, while East, Southeast, and South Asia relied mainly on rice (although the early Chinese societies first relied on millet, before switching to rice). Rice and wheat both produce seeds that are packed full of carbohydrates, as well as some protein and vitamins.

These grains were easily harvested, stored, and transported. This made it possible for Agrarian societies to accumulate the huge stores of food that are necessary for building cities and armies. Without rice and wheat (both of which are grasses), none of this would have been possible.

Because of the bounty from these simple grasses, Agrarian societies all had large, dense populations compared to other simpler societies. Productive agriculture meant more people. Unfortunately, population size quickly expanded beyond the level that the local land could support, so there were always hordes of potential settlers eager for new land. Some found those lands by draining swamps, building irrigation to extend rivers into arid lands, or cutting down forests. The desire for land and the food that could be produced on it was never-ending.

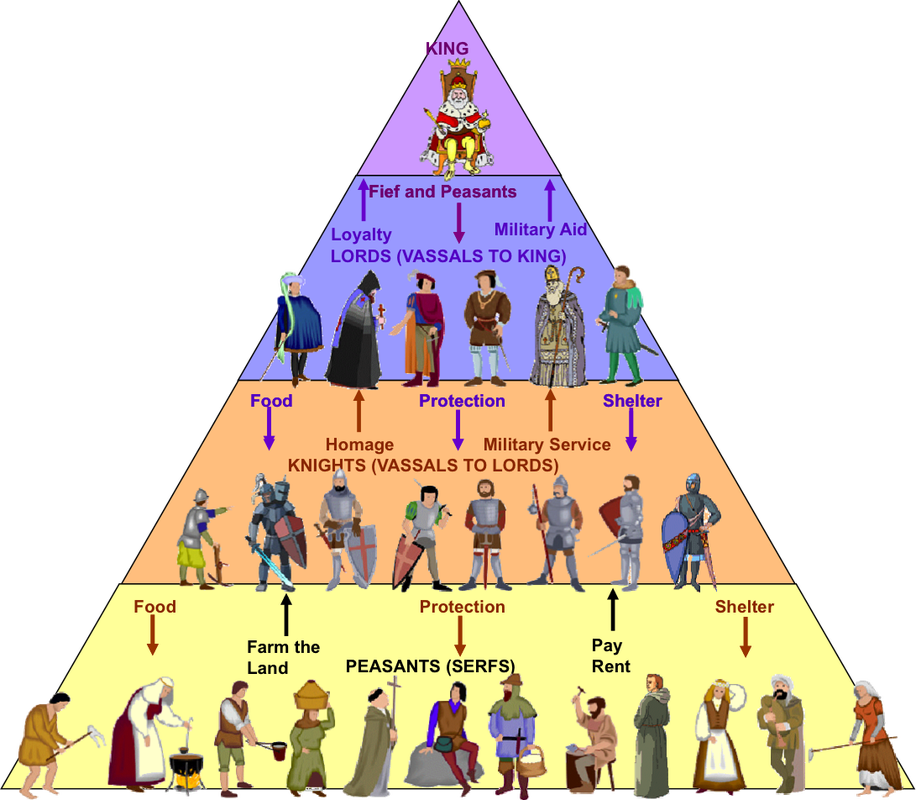

Agrarian societies had an extraordinary level of social stratification. Each had a highly developed system of classes, orders, or castes. Each group separated people based on how they earned a living. Peasants were invariably at or near the bottom. The king or emperor was invariably at the top of the social order. Beneath him were royal bureaucrats, titled nobility, landowners, religious leaders, and military officers. Merchants and artisans were invariably near the bottom, sometimes even below the peasantry, for example in China.

Elites in Agrarian societies were obsessed with status. Each class was denoted by its unique way of dressing, mannerisms, hairstyles, spoken accent, architecture, and more. All of this communicated the message that the membership of each class was closed, immortal, and not subject to questioning. Many Agrarian societies closely tied these classes to religious beliefs that gave the hierarchy even greater legitimacy.

Agrarian societies were similar to Horticultural societies in that both were heavily reliant on agriculture for their food. Agrarian societies were distinct, however, in having large cities with workers specializing in a wide variety of skills. The combination of large food surpluses and specialization of skills enabled a wide variety of political, economic, military, and educational institutions to emerge for the first time.

These institutions concentrated power in the hands of a small elite in huge capital cities: Beijing, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, and Baghdad. This elite acquired their wealth by extracting resources through taxation and land rents. The conspicuous consumption of these elites, a means of flaunting their social status, had the side benefit of supporting large numbers of scribes, artisans, and traders.

Agrarian societies were not the type of societies that would appeal to many modern readers. The peasants did all the work, while the elites extracted the benefits of that work. The few people in between were entirely dependent upon finding favor from elites to get their little piece of those extracted resources.

Because of their dependence on agricultural production, Agrarian societies were extraordinarily rural. Typically, 97 percent of the population lived in rural areas, hamlets, or small villages with a population of under 10,000. The remaining three percent of the population tended to live in one large capital city or one of the regional capitals.

Expansion of Agrarian Societies

One of the most important institutions in Agrarian societies was the military. In previous society types, every able-bodied young man served as a warrior. In Agrarian societies, warriors gradually morphed into a specialized warrior class and finally into professional soldiers and officers.

Armies with bronze, and later iron weapons and armor could conquer large swaths of land that were conducive to animal-driven plows. Except in Tropical regions that could not support plow-based agriculture, a handful of very powerful Agrarian empires absorbed a constellation of smaller Horticultural societies. Only in the Andes, Mesoamerica, New Guinea, and Sub-Saharan Africa were Horticultural societies able to survive, aided mainly by their geographical isolation.

By conquering new lands, Agrarian societies enabled settlers who were hungry for land to migrate into these new territories. Sometimes they settled in previously unused land, while sometimes they used violence to push the previous inhabitants out. But wherever they migrated, the settlers brought with them their genes, technologies, skills, values, and social organizations.

Unlike less complex societies, Agrarian societies could expand into the periphery of neighboring biomes because they had complex military organizations that could support long supply chains. Even if Agrarian societies could not grow crops in a region, they often coveted other critical natural resources, giving them a strong incentive to conquer and colonize less complex societies.

This is particularly true of:

Adjoining Highlands and Deserts with low population densities and valuable mineral resources.

Horticultural societies, which are highly vulnerable to being turned into a dependent laboring class by Agrarian societies, as Horticultural societies have already established a large sedentary population that is conditioned to hard physical labor, but they lack the large armies capable of defending themselves.

(particularly after 1450) Distant coastlines and islands that can be transformed into imperial capitals, trading outposts, and transportation hubs.

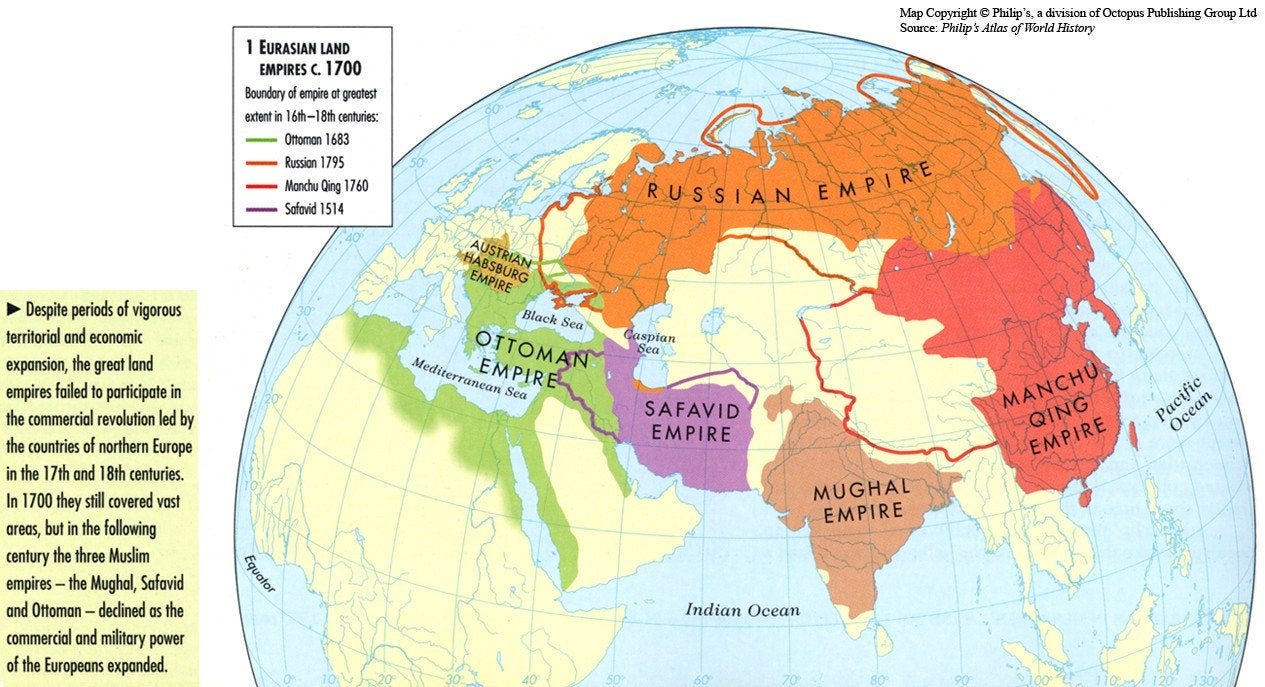

This meant that Agrarian empires were able to conquer large swaths of land that were not suitable for plow-driven agriculture. By the year 1 Agrarian empires had conquered and settled a huge swath of the Eurasian continent stretching from China, through India, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and parts of western Europe. After 1450, Western European Agrarian empires began to expand overseas in Africa, Asia, North America, and South America.

The Legacy of Agrarian Societies

If we assume that a generation lasts 20 years and Agrarian societies emerged in 3000 BCE, by the year 1000 up to 200 generations had lived in an Agrarian order. Two hundred generations of people living where taking was more beneficial than creating had a profound effect on how people thought. People assumed that it was better to accept their fate and resist change because change would likely be bad. Peaceful cooperation between strangers for mutual benefit did not play a role in how these people saw the world.

While the legacy of previously discussed Society Types towards the promotion of progress was quite negative, the legacy of Agrarian societies is more mixed. It is striking that none of the early leaders in innovation and progress (Northern Italy, Flanders, the Netherlands, Southeast England, and the United States) were Agrarian in the year 1500. Agrarian societies, while they inherited a large base of technology and large cities, tended to stifle innovation.

On the other hand, it is also interesting how many of the nations that have been able to industrialize within the last 150 years were previously Agrarian societies. These include Germany, France, Russia, Japan, South Korea, China, and India as well as large swathes of the rest of Europe and Asia.

While no society or minority that is a descendant from Hunter-Gatherer, Fishing, Herding, or Horticultural societies in the year 1500 has been able to achieve rapid growth in wealth without the aid of extracting fossil fuels, dozens of Agrarian societies have been able to do so. Immigrants from societies that were Agrarian in 1500 have been able to prosper throughout the globe (Chinese, Indians, Jews, Lebanese, Germans, and Japanese).

In my next post on this series on the impact of society types on human history, I will explain Herding societies.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my other articles on Society Types and related topics:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Agrarian societies (this article)

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)

Great article! Very interesting 🙌

"On the other hand, it is also interesting how many of the nations that have been able to industrialize within the last 150 years were previously Agrarian societies. These include Germany, France, Russia, Japan, South Korea, China, and India as well as large swathes of the rest of Europe and Asia."

Great write-up here. I am working on a few essays regarding the agricultural revolution as well.

I am not 100 percent certain, but it seems to me that the list below contains countries that went through some kind of significant land reform before they industrialized.

Perhaps a one-time “reset” was needed to overthrow the extractive agrarian regimes?