I believe that there have been four great transitions in human history:

The advent of anatomically modern humans and the invention of the Hunter-Gatherer lifestyle.

The invention of agriculture, which created Horticultural societies.

The evolution of Commercial societies, which invented human material progress.

The Industrial Revolution

Today, I am going to talk about the second transition and the society type that came out of it. Horticultural societies are a type of society that produces the majority of its calories from either:

Farming domesticated plants (using hand tools)

Sometimes also raising domesticated animals.

You can think of Horticultural societies as “Gardening” societies because many of the tasks of modern backyard gardening were very common in Horticultural societies. Famous examples of Horticultural societies include the Aztecs and Incas. This type of society has dominated the regions of South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea for millennia.

Because of the unique character of these types of food, Horticultural societies were very different from other types of societies.

See also my other articles on Society Types and related topics:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Horticultural societies (this article)

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. It is part of a series of excerpts that I am publishing on Substack. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Horticultural Societies

As Peter Bellwood and many others argue, one of the greatest innovations in human history was learning how to cultivate grain. Humans can consume a remarkable range of plants. We consider approximately 7000 plant species to be edible.

Despite this diversity, the majority of the calories consumed by humans throughout the last few millennia have been from a very small list of staple crops: rice, wheat, corn, and potatoes. If one adds in a few more related cereals like oats, rye, barley, and millet, a slightly longer list of foods has supplied over 80% of global food needs.

Except for potatoes, all of these crops are closely related to each other. They are all cereals from the Poaceae family, more commonly known as grass.

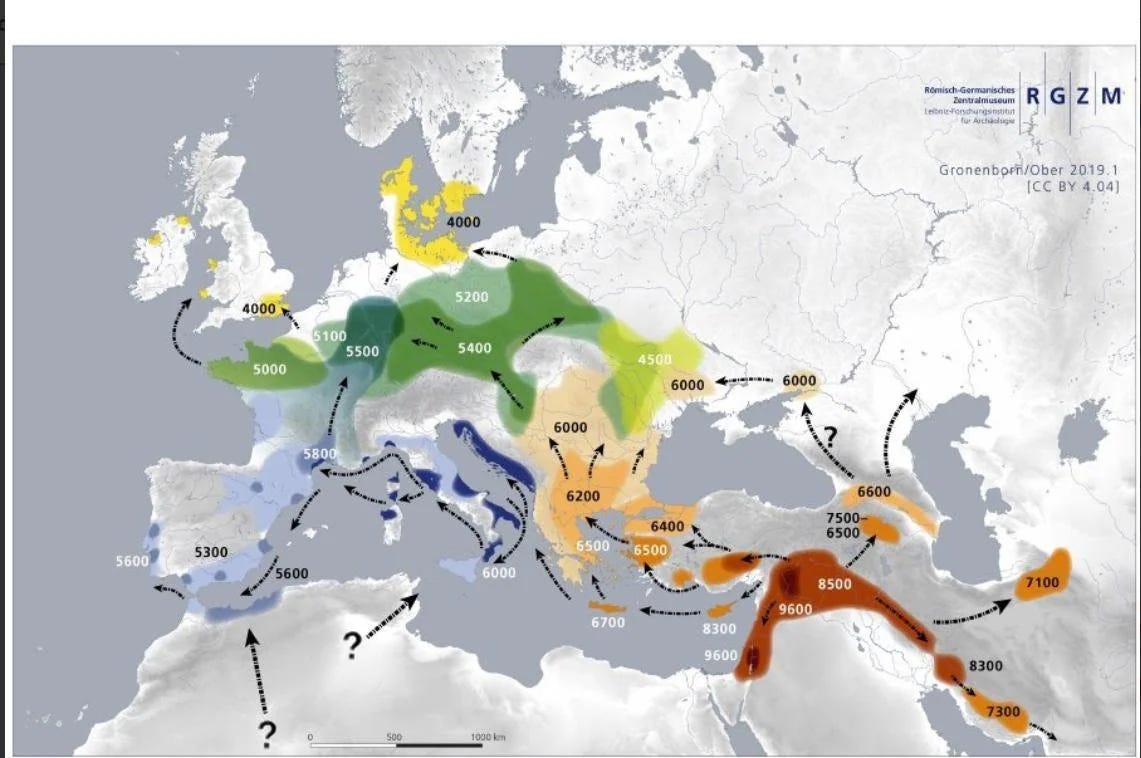

It seems highly likely that Hunter-Gatherer societies had always gathered wild grain where it was available. Unfortunately, outside of Temperate Grasslands, most ecosystems lacked this crucial energy source. Around ten thousand years ago in the Hilly Flanks of modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Southern Turkey, some societies began to experiment with harvesting wild grain (such as wheat and barley) on a much larger scale.

These grasses packed far more energy per unit of labor and grew across far wider swaths of land than any existing food sources, so many people sought to harvest these wild plants. As the scale of production increased, these societies shifted consumption heavily towards these plants and invented new technologies to cultivate and store these grains.

The people of the Hilly Flanks (the upland edges of the Fertile Crescent) also played an important role in domesticating cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep. These animals were highly important to survival, as they possessed the ability to digest cellulose, the dominant portion of grains. While humans could neither eat nor digest the cellulose that was all around them, they were able to eat the cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep that could do so. In this way, humans innovated a means for turning a very widespread natural resource into food.

The people of the Hilly Flanks devoted more and more time to cultivating grasses and domesticated animals, forcing fundamental genetic changes in both the grasses and themselves. Most importantly, these behavioral changes forced people to evolve the ability to digest glucose and build up biological resistance to diseases transferred from domesticated animals. People domesticated the grasses and herd animals, but the grasses and farm animals also domesticated the people.

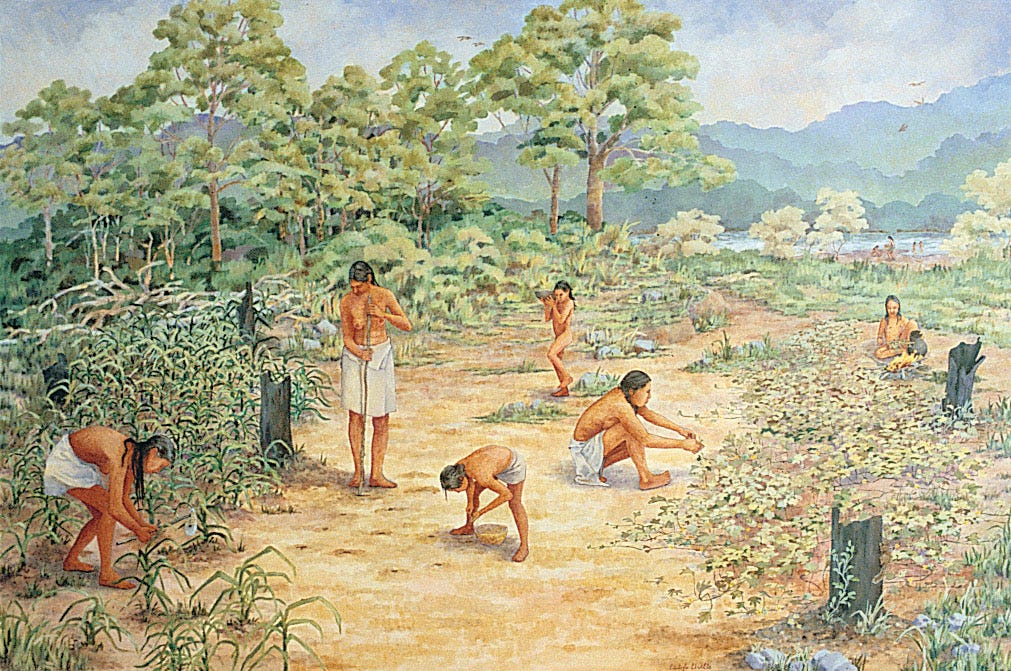

Eventually, the Horticultural society evolved, in which the bulk of people were engaged in harvesting domesticated grasses, animals, and other staple crops. Unlike later Agrarian societies, they lacked animal-driven plows, so all of the work had to be done by simple hand tools. You can think of these people as gardeners, who used methods very similar to what people today use in their backyard gardens.

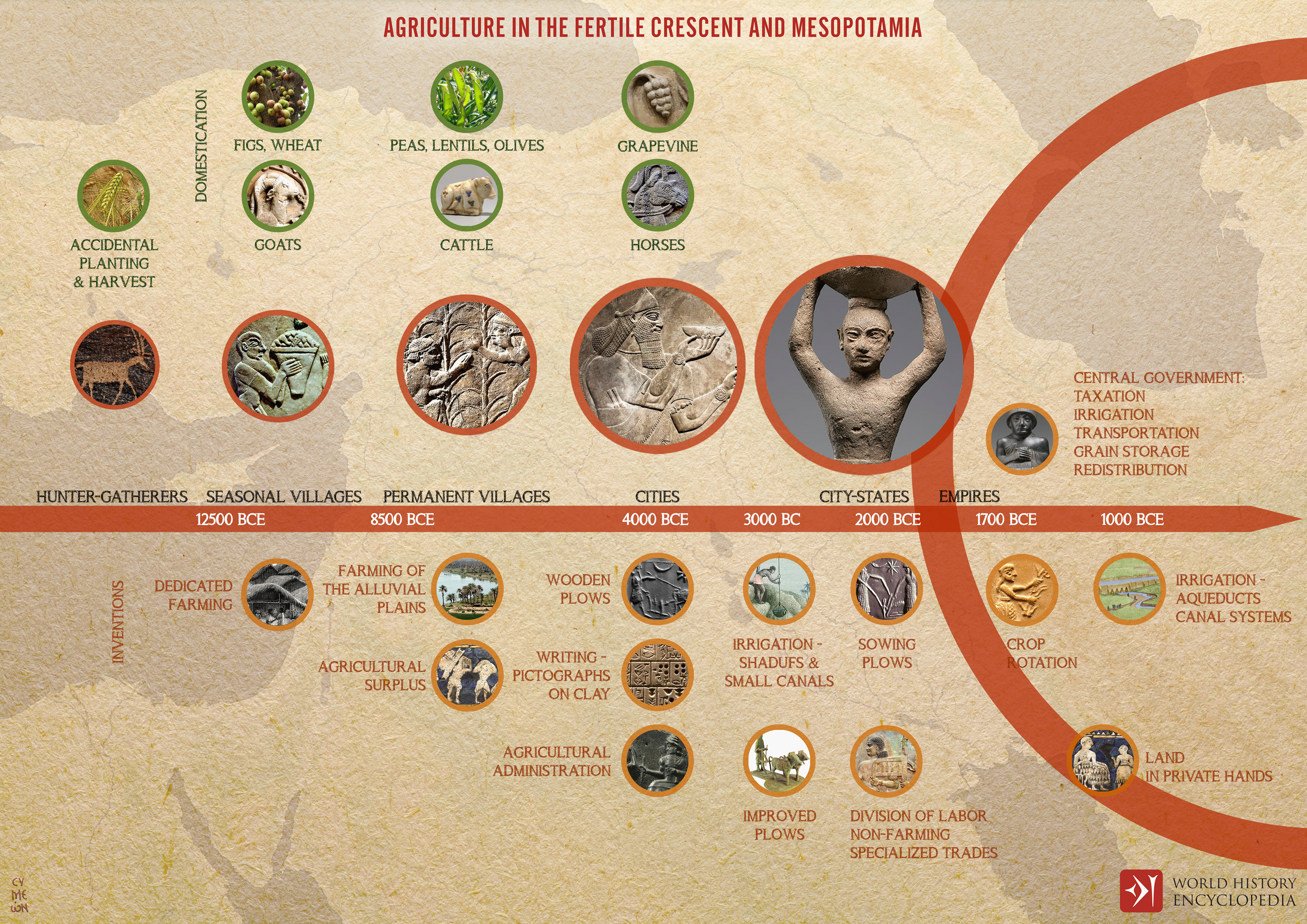

Take a look at the above graphic, which I explain in greater detail here.

Horticultural societies evolved out of Hunter-Gatherer societies sometime around 7000 BCE (i.e. roughly 9000 years ago) in what was likely a Mediterranean biome on the Hill Flanks. Key technologies enabled Horticultural societies to do the following:

Domesticate wild grains, particularly rice, wheat, sorghum, and millet (using a spade, hoe, and other hand tools)

Domesticate wild herbivores, particularly cows, goats, pigs, and sheep.

Store and transport their grain (using pottery and granaries)

Wage war against other humans (using bronze weapons and armor)

This suite of new subsistence technologies for growing, storing, and transporting domesticated grasses created such a large energy surplus that much of it could be used to support the earliest cities and towns.

Horticultural societies generated far more calories per human than Hunter-Gatherer societies, and they were not restricted to rivers and coastlines as Fishing societies were. This meant that Horticultural societies could expand far beyond their original borders.

Horticultural Societies Migrate

Except in regions along large rivers or where the soil was very rich, Horticultural societies practiced slash-and-burn hand tilling that ruined the local soil productivity within a few generations, so farmers always had an incentive to move to new areas. With simpler technology and much smaller population sizes, neighboring Hunter-Gatherer societies were at a distinct military disadvantage. Migration by farmers in search of fertile soil gradually forced Hunter-Gatherer societies to retreat until they fell back to regions that were less hospitable to slash-and-burn gardening.

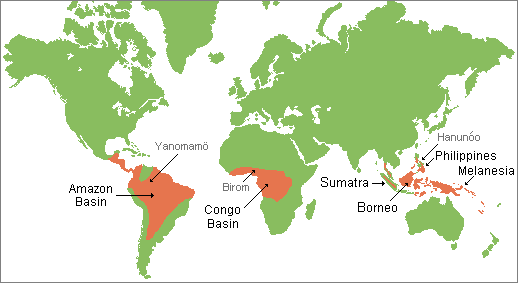

Horticultural societies eventually spread to most regions within the Mediterranean, Temperate Forest, Tropical Forest or Tropical Highland biomes. This created a broad belt of Horticultural societies running from East Asia to Europe, as well as a few isolated areas on other continents such as New Guinea, the African Sahel, Mesoamerica, Amazonia and the Andes.

The populations of these Horticultural societies became particularly large and dense along large river valleys, such as the Nile, Tigris/Euphrates, Indus and Yellow Rivers. The rest of the world, however, still lived in Hunter-Gatherer and Fishing societies, because these people lived in environments that could not sustain Horticultural societies.

By the year 1000, most Horticultural societies in Eurasia had already transformed into Agrarian societies. Wherever the environment enabled animal-driven iron plows, purely Horticultural societies had gone extinct.

The bulk of the Horticultural societies in 1500 were in Eastern North America, Central America, South America, Africa, New Guinea and mountainous parts of Southeast Asia. All of these areas lacked the wild ancestors of horses, cows, and water buffalo that were used to pull iron plows.

So the invention of agriculture was one of the greatest innovations of human history, but did it lead to progress that benefitted the masses? It certainly increased their ability to produce additional calories. It also enabled the growth of large cities and expanded the technology base. For the first time, a portion of humanity could focus on solving problems other than producing food.

Unfortunately, the biggest impact of this increased food surplus was to have more babies, which created more mouths to feed. So in the long run, the increased wealth led to a larger population size rather than a wealthier population. In addition, political leaders, religious leaders, and warriors probably expropriated the bulk of the food surplus. Even worse, diseases transmitted from domesticated animals were a constant threat.

The Horticultural era resulted in progress for the elites, but it is difficult to find much evidence of progress for the masses. The formation of cities undoubtedly accelerated the rate of innovation and made it much easier for those innovations to diffuse throughout urban populations, but it is clear that the benefits were largely enjoyed by the elites.

By the Metrics

Compared to earlier Hunter-Gatherer and Fishing societies, Horticultural societies had:

Sedentary population (although early versions practiced slash-and-burn once soil loses its fertility)

The very first cities. Capitals of great empires could grow to an enormous size. Examples include:

Jericho (in modern-day West Bank)

Catalhoyuk (in modern-day Turkey)

Byblos (in modern-day Lebanon)

Erbil (in modern-day Iraq)

Damascus (in modern-day Syria)

Ur (in modern-day Iraq)

Nojpeten (capital of the Itza Maya empire in modern-day Mexico)

Monte Alban (capital of the Zapotec empire in modern-day Mexico)

Tenochtitlan (capital of the Aztec empire in modern-day Mexico)

Cusco (capital of the Incan empire in modern-day Peru)

Each region was based on a very small number of staple crops:

Rye, barley, oats, wheat (Middle East, Europe, and Indus river valley)

Millet and later rice (East Asia)

Rice (Southeast Asia and Ganges river valley)

Maize and beans (Meso-America)

Potatoes (Andes region)

Sorghum and yams (Africa)

Cassava (Amazonia)

Very high rates of warfare (as tribes and kingdoms fought over arable land and women)

Governance is typically by:

Higher levels of technological complexity

Higher levels of long-term food storage once granaries were invented.

Much higher levels of population

Much higher population density, particularly where the soil was fertile and rivers were nearby

Much greater levels of economic and political inequality (political leaders who controlled the food storage were common)

Increasing specialization of elites:

Political leader (big man, chief, clan leader)

Warriors

Priests

Much higher rates of forced labor (slavery was common)

Were restricted geographically by biome, soil type, and altitude.

Polygamy was often the most common form of family

Highly developed religions that often left behind impressive monuments

All of the above were the direct outcome of the much higher energy density of grains and root vegetables compared to other plants. It is important to note that later Agrarian society types surpassed Horticultural societies on almost every metric listed above

Examples of Horticultural societies

Examples of Horticultural societies in history include:

The original agriculturalists in the Fertile Crescent.

Incans of Andes mountains

Yanomami of Amazonia

Bantu peoples of Western and Central Africa

African Sahel

The Legacy of Horticultural Societies

The legacy of Horticultural societies still lives with us today. The ancestors of Horticultural societies in the year 1500 (i.e. just before the European conquests) have struggled to prosper.

Native Americans in both North and South America, Sub-Saharan Africans, New Guinea, and the mountainous parts of Southeast Asia are all either very poor nations or relatively poor minorities within more prosperous nations. To the best of my knowledge, no significant ethnic group descended from Horticultural societies in 1500 is above average in income or social status within their nation.

In my next post on this series on the impact of society types on human history, I will explain Agrarian societies.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. It is part of a series of excerpts that I am publishing on Substack. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my other articles on Society Types and related topics:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Horticultural societies (this article)

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)