Why you need to know about Society Types

Because you are what you eat.

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

In previous articles on the Substack column, we have seen that human societies have gradually overcome the constraints to progress by innovating technologies, skills, and organizations for turning the energy of the sun into useful technologies. But how did this happen? How did human societies evolve from small bands roaming the African savanna into complex societies capable of harnessing enormous amounts of energy and complex technologies?

To explain how humans escaped the traps created by constraints to innovation and progress, we must briefly overview human history. In the distant past, change, let alone progress, was not part of anyone’s experience. A person’s daily life was pretty much the same as their parents, their grandparents, and their great-grandparents.

The most important changes within a person’s lifetime were sudden and negative: droughts, crop failures, famines, wars, and epidemics. Once the effects of these deadly events wore off, life returned pretty much to the way it had been… at least for those who were lucky enough to survive.

Traditional Chinese concepts of history understand history as a cycle. Change occurs, sometimes even something resembling progress, but then the cycle reasserts itself to reset things back to the way they were. I think this view adequately represents most of the world up until the 20th Century.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

You might also be interested in reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See also other posts on related topics:

Why you need to know about Society Types (this article)

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)

Society Types

Human societies have not been the same across the globe and across history. Mainly because of geographical variation, very different types of societies evolved in different parts of the globe.

While they each had important cultural differences, it is most convenient to categorize societies into what anthropologists and sociologists call “society types.” The concept of society type enables us to overview human history without going into all the details that were only relevant in the short term.

A society type is a category for how a society organizes itself to transform energy and other natural resources into food and other useful technologies. This is most easily measured by how people acquire a majority of their calories. If, as they say, “you are what you eat”, then the society type concept emphasizes that “we are how we acquire what we eat.”

When viewed from the highest level, there are only a small number of means through which a society can acquire enough calories to survive and reproduce. The following is a list of society types and how they acquire the majority of their calories:

Hunter-Gatherer societies: Hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants.

Fishing societies: Fishing, hunting sea mammals, and gathering shellfish.

Horticultural societies: Farming domesticated plants (using hand tools) and sometimes also raising domesticated animals.

Agrarian societies: Farming domesticated plants (using animal-driven iron plows) and raising domesticated animals.

Herding societies: Herding domesticated animals on the wild range.

Commercial societies: Selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the market (but with limited use of fossil fuels).

Industrial societies: Selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the market and widespread use of fossil fuels.

Note: I also find it useful to use the following categories:

Agricultural societies = Horticultural + Agrarian societies.

Traditional societies = All society types except Commercial and Industrial.

Complex societies = Agrarian + Commercial + Industrial societies

Some researchers also use the term “Foraging societies” to mean Hunter-Gatherer and Fishing together, but I think that this causes more confusion than clarity.

Origins of the Concept

While they did not use the term, the concept of Society Types first became popular during the Enlightenment in the 18th Century. Early thinkers on the subject widely believed that human societies naturally progressed from simple to complex. This created a very linear view of human history. This way of thinking is sometimes called the “unilineal evolution of societies.”

For example, most Enlightenment thinkers believed that all societies started as Hunter-Gatherers, then at some point transitioned into Herding societies, and then at a later date, they transitioned into Agricultural societies.

Adam Smith (whose statue at the top of this article) and some thinkers within the Scottish Enlightenment added a fourth type of society, Commercial societies, to explain the transition going on at that time. Adam Smith thought all societies would transition through all the other society types until they inevitably transitioned into modern Commercial societies. In fact, Adam Smith's classic work, The Wealth of Nations, came directly out of his desire to understand how Commercial societies function.

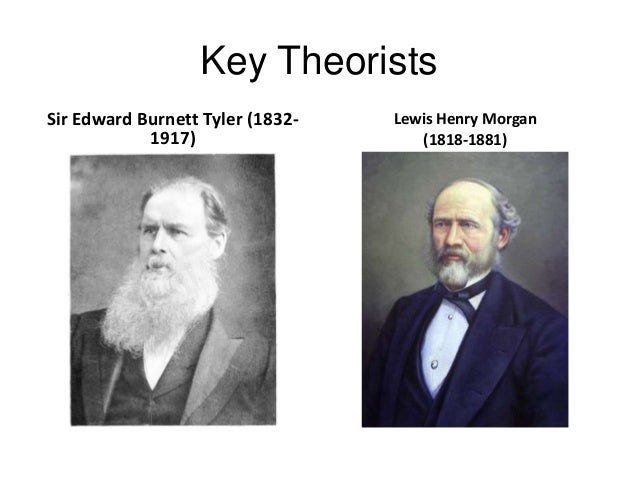

Later in 19th Century, thinkers such as Henry Home, Edward Burnett Taylor, Lewis Henry Morgan developed more complex versions of the theory. In the 20th Century, Julian Seward and Gerhard Lenski further developed the concept. At one time, Society Type was a dominant paradigm in anthropology and sociology, but it has lost favor within those fields.

Let’s not throw out the baby with the dirty bath water

I believe this is an overreaction to the overly simplistic application of early versions of the concept. If we apply an evolutionary perspective, we can see that just as animals adapt to their natural environment, humans adapt to their social environment (i.e. Society Type), which in turn is an adaptation to their natural environment.

None of these adaptations are inherently superior to the others. Specific adaptations promote survival and reproduction in a specific environment. Those same adaptations may not work particularly well in a different environment.

Virtually all energy in human societies ultimately derives from the sun. Societies use different technologies, skills, and social organizations to transform solar energy into food that is fit for human consumption. In this way, large groups of people can survive and reproduce. How they do so, however, varies greatly between societies.

It All Comes Down to Food

But why is food consumption so important that we can categorize entire societies by it? The reason is that until very recently, by far the most time-consuming task in people’s daily lives was in acquiring food. Other than sleep, the bulk of people’s time has been allotted to producing, preserving, storing, distributing, preparing and eating food. And much of the time left over has been devoted to building and repairing tools necessary for those tasks.

Because so much time and energy was needed to acquire food, entire societies were forced to organize themselves around the optimum means of doing so within their local environment. Because of environmental limitations, the limited number of skills that any one person can acquire, and the need for people to cooperate within social organizations, societies must specialize in one specific means of acquiring food.

For example, a group of people in one geographical area cannot simultaneously specialize in both fishing and farming. In any one geographical area, one of these means of acquiring food generates more calories of food per unit of work than others, so most people will naturally focus their efforts on that type of food.

This does not mean that an individual human can only focus on producing one type of food. A farmer, for example, may go fishing in the local stream at a time when farm work is not needed. That individual may even specialize in fishing and provide extra protein for the entire village. But the overall consumption of the village and surrounding region would be largely from domesticated plants and animals.

A very large polity may have different regions specializing in different means of subsistence, but each region must specialize in the means that is most effective at generating calories of food per unit of work. The level of technology, available energy and natural resources determines which means of subsistence is most effective.

The vast majority of societies throughout history fit comfortably into one of the types listed above (although polities often span multiple society types). The exceptional societies that cannot be fit into a type have had relatively little impact on history. Societies do not persist on the edges of a type for long (i.e. 55 percent of calories from one type of food and 45 percent of calories from another).

Again, each society must focus its efforts on the most productive means of acquiring food that the environment can provide. To do otherwise threatens the ability of the group to survive and reproduce.

The Usefulness of the Concept of Society Type

While many historians and anthropologists would undoubtedly bridle at such a gross over-simplification of each society, I believe that Society Type is a useful concept for the following reasons.

Almost all bodies of human knowledge use classifications to promote our understanding. Geologists group clusters of years into eons, eras and periods; Chemists group types of atoms into elements on the Periodic Table; Biologists group individual plants and animals into domains, kingdoms, phylum, classes, orders, families, genus and species.

All of these classifications simplify by categorizing individual items into groups based upon relevant characteristics. All are open to the charge of over-simplification, but all these categorizations have stood the test of time because they are useful. They are useful because they focus on differences that matter while ignoring less important differences.

The concept of Society Type is useful because with one simple label we can communicate a large number of important characteristics about any given society in history. We will cover these characteristics in much greater detail later, but for now, it is sufficient to say that each type has common levels of:

population size

population density

political structure

economic structure, and

rates of innovation.

And these characteristics differ from societies of other types.

The concept of Society Type enables us to understand why some groups of people evolved culturally at vastly different rates than other groups of people. This is because the society type is to humans what the natural environment is to animals: the critical environmental factor that drives evolutionary change. Among animals, that evolutionary change is entirely genetic. Among humans, that evolutionary change is genetic, cultural and technological.

Humans adapt to their society type through changes to their genes, culture, technology, skills and social organizations. Any factors that fundamentally conflict with survival and prosperity in their society type will be under substantial pressure to change.

With adaptation via innovation and diffusion, each generation is slightly better adapted for surviving, reproducing, and prospering in that society type than the previous generation. Within a single lifetime, the changes can seem trivial, but when viewed from the perspective of centuries, these changes can be dramatic.

The concept of Society Type enables us to understand why some nations today are much wealthier than others. Hunter-Gatherer societies are uniformly poor by the standards of any other society. Horticultural, Agrarian, Commercial, and Industrial societies were step-by-step wealthier than the previous society, although before Commercial societies the masses did not material benefit from that wealth. And the gulfs between societies of different types were usually vast in size.

The concept of Society Type also enables us to understand why different ethnicities within the same country are much wealthier than others. People whose ancestors were recently from Hunter-Gatherer societies have had a very difficult time prospering in other society types. Immigrants who descend from peoples that lived in Horticultural societies have also struggled to adapt to living in more complex societies, despite the greater opportunities. People from Commercial and Industrial societies have prospered wherever they have immigrated.

The concept of Society Type enables us to understand the daily lives of most people within a society. We have already seen that until the Industrial era, the overwhelming majority of people in all societies did the bulk of their labor acquiring food. And the processes that they developed to grow, distribute, and store food played a powerful role in structuring the entire society. For this reason, food production should define how we categorize societies.

The food production system largely determines the amount and type of energy that a society can consume. This energy can then be used to innovate new technologies, skills, and social organizations that solve key problems.

With relatively inefficient food production, very little energy can be devoted to innovation. Virtually all of it is consumed by survival and reproduction. But as the food production system becomes more efficient, then greater amounts of energy can be devoted to the innovation of new technologies, skills, and social organizations.

Society Types Are Not Moral Judgments

One of the most common arguments against the concept of society types today is that the concept confers a supposed moral superiority of some societies over other societies due to them being more advanced. While many thinkers during the Enlightenment and the 19th Century thought some human societies were morally more advanced than others, there is no reason to do so today.

This moralistic framework is categorically false. Society types are about the survival and reproduction of entire societies. A society is either adapted to its natural environment and the people living within them or it is not. Members of that society may be perfectly adapted to living within that type of society, but when they go to another type of society or another geographical environment, they will literally become “fish out of water” (i.e. in grave danger of not surviving).

Rather than using terms such as “advanced” and “primitive”, I use the terms “complex” (i.e. with a great deal of internal differentiation and sub-groups) and “simple” (i.e. with relatively small amounts of internal differentiation). This way, there is no moral judgment conferred, no more than when chemists talk of simple or complex compounds of chemical elements.

As I will explain later, Commercial and Industrial societies have an internal dynamic that creates progress. I believe that this progress leads to such immense material benefits for humanity, that they are morally preferable to other society types.

But even that argument makes no moral judgments between Agrarian, Horticultural, Herding, Fishing, and Hunter-Gatherer societies. These different types of societies are just different adaptations to a specific natural geography given the technology that had existed at the time.

Society Types Are Adaptations

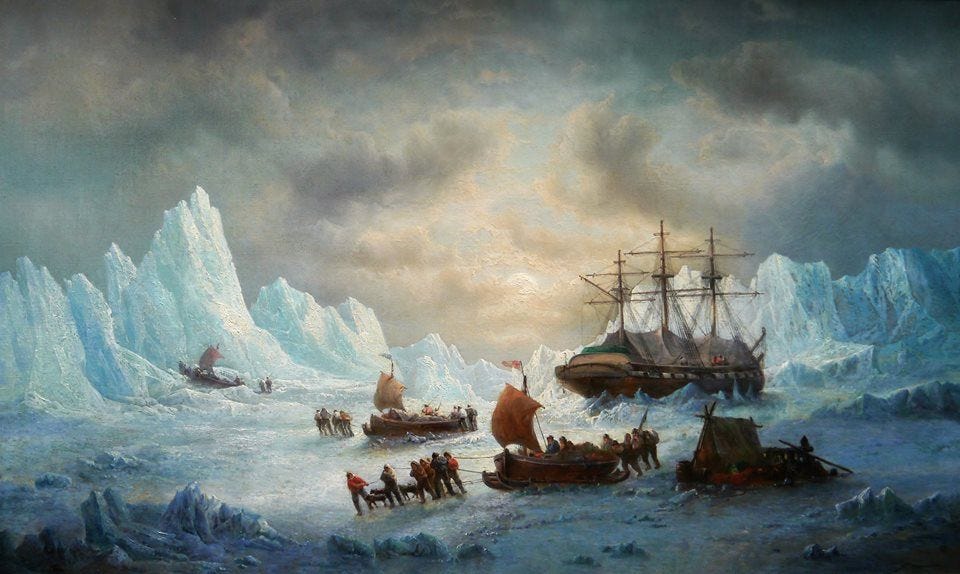

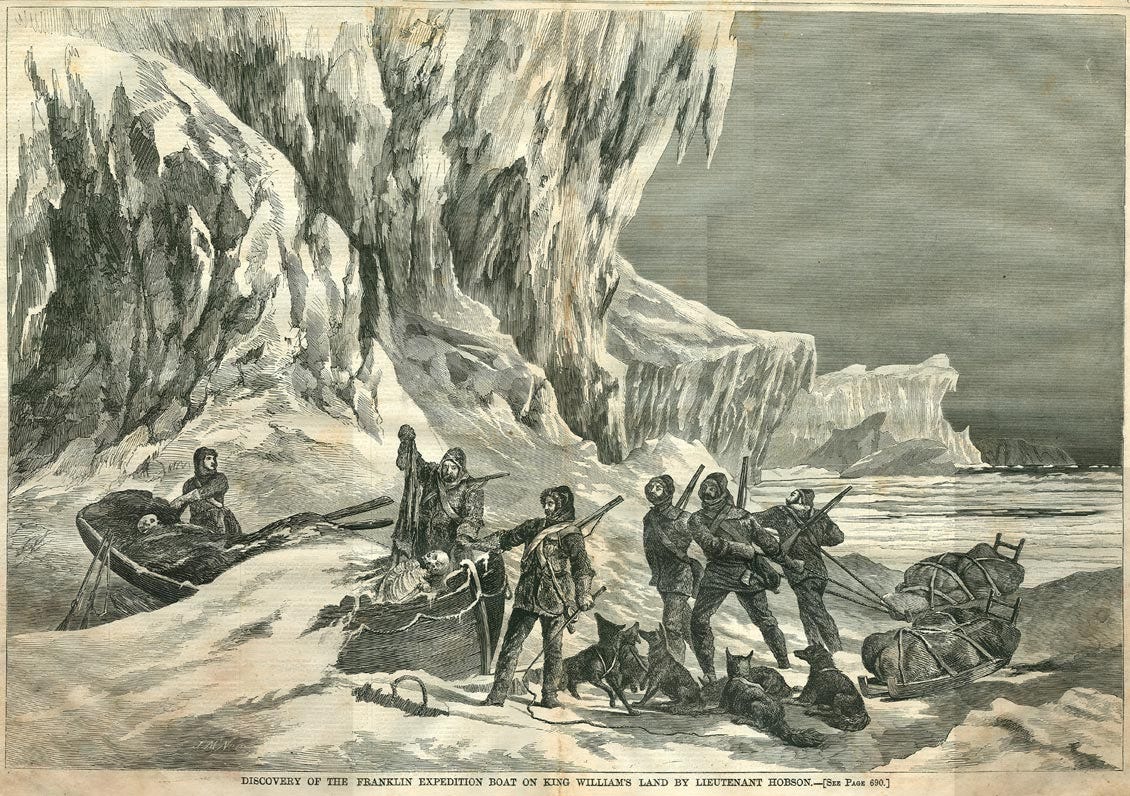

In his outstanding book The Secret of Our Success Joseph Henrich gives a compelling example of how difficult it is for people living in one society type to transfer their success to another environment. In 1845, two British ships searching for the Northwest Passage were shipwrecked on King William Island in northern Canada. No one knows their full story, but we do know that none of them survived.

The sailors on the ship were members of the richest and most technologically dynamic society at that time. Their ancestors had innovated an incredible number of technologies, learned new skills and cooperated in highly complex organizations.

The British at that time were at the pinnacle of human achievement. But the skills, technology, values and organizations that enabled the British to prosper in London or onboard ships were almost useless to survive on an island in northern Canada. None of the crew of 129 survived the ordeal.

At first impressions, this should not be a surprise. Northern Canada is a very hostile environment. No one could survive such a hostile environment without help from outside.

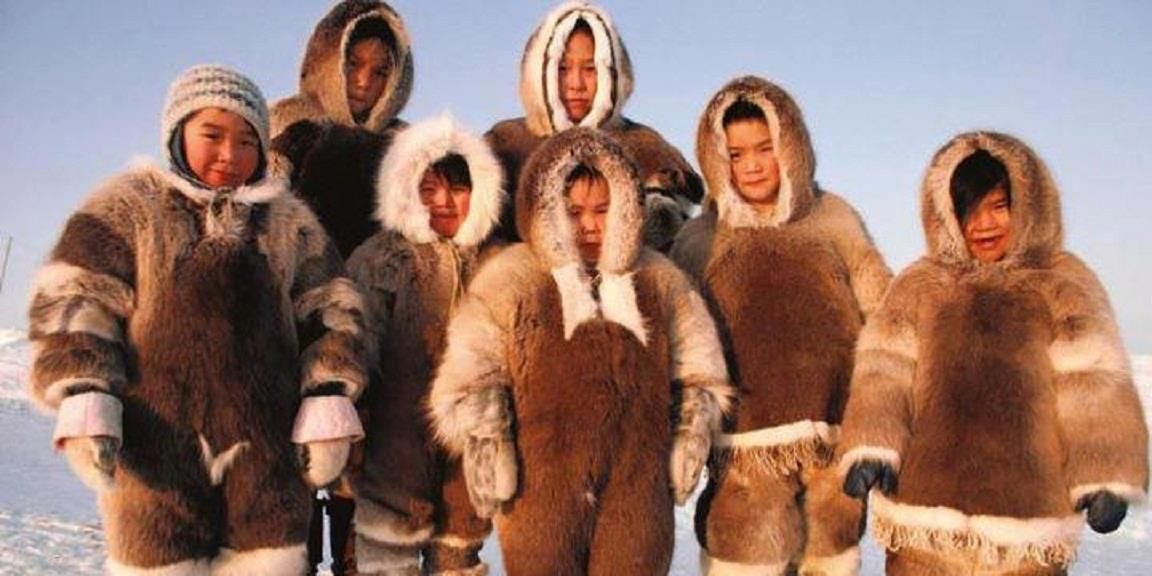

One might think so, but the local Inuits had survived and prospered in that land for about 800 years. The technologies, skills, social organizations and values of the Inuits were very simple in comparison to what the British had innovated, but that did not matter.

What mattered is that the Inuit technologies, skills, social organizations and values were perfectly adapted to that polar environment. Inuits were neither inferior nor superior to the British. If Inuits had suddenly been transported to Britain, they would have struggled as well. Perhaps they would have been able to survive better than the shipwrecked British crew, but it is doubtful that they would have done as well as a typical British person.

Every Inuit child was taught from birth the skills, social interactions and values needed to survive and reproduce in that polar environment. This made each child the benefactor of centuries of trial-and-error experimentation by their ancestors that led to key technological innovations such as kayaks, snow houses and cold-weather clothing.

Inuit boys were taught by their fathers how to hunt seals, build and repair kayaks and spears, predict the weather and a myriad of other skills. Inuit girls were taught how to preserve and prepare food and tailor cold-weather clothing. Both girls and boys learned how to cooperate in the types of social groups necessary to survive in the polar environment.

Over the generations, Inuits built Fishing societies adapted to survive in environmental conditions that would terrify most other people. This did not make them superior, just better adapted to a specific local environment.

If forced to live in a very different natural or social environment, the Inuits would have had a very difficult time surviving. Even if they somehow were able to survive and thrive, it would be because they were able to rapidly copy members of a society that were already better adapted to the new environment.

See also other posts on related topics:

Why you need to know about Society Types (this article)

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

Commercial societies (which invented modern progress)

If you want a much deeper dive into the concept of Society types, I would recommend reading these posts on my online library of book summaries:

“Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology” by Nolan and Lenski

“Economic Systems of Foraging, Agricultural, and Industrial Societies” by Frederic Pryor

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

You might also be interested in reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Good to have a review opportunity a year later.

Thinking about the society categorization along food production lines, with energy modes available as a close parallel support role, I was wondering if you or others had also considered the role of information communication, transfer, and learning as a parallel vector or alternative mode of categorization.

When I think about those videos of some researcher developing the skills to make stone tools by hammering one stone against another, with a piece of leather on his knee or lap, I can see that even that "primitive" development required considerable experimentation, patience, mechanical skills and dexterity, etc. But also once a "production" technique was established, then a real "business" in suitable flint stone sources or locales could be mined and used for trade with other groups. [Based on my 1990 visit to the display of such a mine exhibit at the British Museum :-) ]

What is tricker to understand is why such stone tool advances were so few and infrequent over very extended periods. [Perhaps this recent analysis of suggested genetic mixtures between smarter and less smart hominid groups is involved: www.razibkhan.com/p/homo-with-a-side-of-sapiens-the-brainy Probably still pretty conjectural at this stage. Plus, possibly use of wood, bone, etc. for tooling did not survive long enough to show up? ]

On the commercial vs. industrial groupings, I can expect that early commercialization was pretty much fabricator to customer type markets [or "faires"], but did they evolve to using brokers and warehousing as middle men in the distribution, presumably for trade via shipping, etc.? Or is that aspect still only showing up with greater "capital" requirements and industrial level output?

Great set of categories, based on availability of food and the work effort required to obtain it. Such a top level and over arching viewpoint seems reasonable to me - but as you say, honest (tactful, respectful) critique can lead to enhanced understanding.

Are there any metrics of such energy expenditure per capita or per man-hour that might support your thesis, presumably with at least a modest if not appreciable step function over the previous threshold?

I suspect even SWAGs would be educational and illustrative (with suitable caveats).

Unfortunately it appears that there are 5 or 6 different ways of expressing energy and power within the English and the metric measuring systems. Hard to remember all of the conversions, etc.