Can a Land Value tax make housing affordable?

Change the incentives of landowners by changing the tax code.

In previous excerpts (here and here) I made the case that unaffordable housing is one of the Western world’s biggest problems, and it has emerged only recently due to bad government policy. In another excerpt, I made the case that YIMBYs are only 50% correct, because they view urban sprawl as something to be fought against and urban density as something to aspire to.

In my previous post, I listed some incremental policy reforms that will help to make housing more affordable. In this post, I will get more radical, by George…

In the late 19th Century, Henry George (shown above) was one of the most influential men in America. His political views were what appears today to be a bizarre blend of left-wing radicalism and right-wing libertarianism. George believed that industrial progress and capitalism were good things, but the benefits of that progress were overwhelmingly going to landowners who contributed little to economic growth. The focus on land instead of capital or labor may seem old-fashioned, but it is far more relevant than you realize.

Let’s see why land prices are still central to many of our housing problems today.

Most of the following is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

Can a Land Value tax make housing affordable? (this article)

It Is All About Land Prices

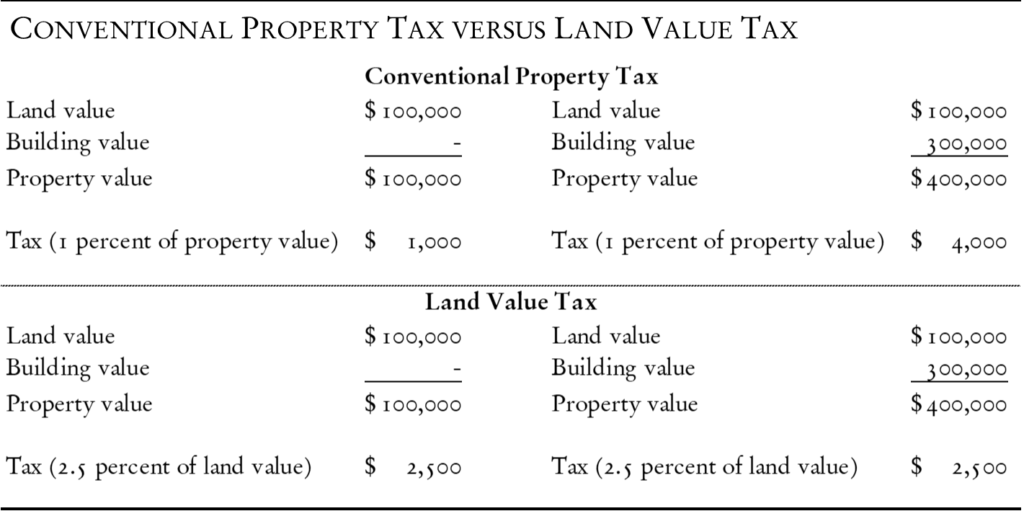

Currently, property taxes are a major source of revenue for local and state governments. Property taxes are based on the assessed value of both the land and all structures on that land. This means that owners of empty plots of land pay much lower taxes than owners with buildings on their land. In metro areas where the price of land is going up, landowners increase the value of their portfolio by doing nothing. This creates a strong incentive for land speculation.

What is effectively happening in many major metro areas is that entrepreneurs, engineers, and other workers create wealth that benefits all of society. Unfortunately, because of the artificial scarcity of land in that metro area, a highly significant proportion of the wealth creation goes to those who own land near those industries. Those rentier landowners need to do absolutely nothing to experience massive increases in wealth. Meanwhile, the young, poor, and working class must deal with ever-increasing housing costs, which sap their ability to enjoy the benefits of living in a productive economy.

If you do not believe me, check out the housing prices in California, Hawaii, Seattle, Portland, New York City, and Boston. Expensive houses, right? Well, no: expensive land under the housing!

Take a look at the American Enterprise Institutes Land Share Indicators for 2012 and 2020. The share of the cost of land in all those cities listed above is over 60% of the total cost of houses. For Los Angeles and San Francisco it is over 70%. In comparison, most metro regions have land shares of 25-53%.

And the overall land share is increasing over time. In 2012, land made up 38.2% of the total value of all residential real estate. In 2020, land made up 54.7% of the total value. Given that real estate values increased overall during that period, this is an enormous increase in the cost of land. And that land inflation is concentrated in a few dozen expensive metros.

Increased Inequality of Wealth

The widespread inflation of land values within cities that have urban containment zones has had a huge effect on the distribution of wealth. Indeed, Matthew Rognlie makes the compelling argument that increased inequality in wealth over the last few generations is entirely due to housing inflation (or more accurately the inflation of the cost of land under that housing). Ironically, the liberals who complain the most loudly about inequality are the ones who created the problem and are the main beneficiaries of this trend (Rognlie).

Because residential real estate makes up a very substantial portion of all wealth in American society and variations in the value are largely determined by policy, homeowners in metro areas on the Pacific coast and Northeast have enjoyed huge increases in personal wealth over the last few decades. And they have enjoyed those increases of wealth, not by increasing their wealth via work or innovation, but by extracting wealth from land ownership.

While some of this wealth goes to members of the working class and retirees who were lucky enough to purchase homes before the big inflation started, the benefits overwhelmingly go to the professional class. And the pain goes overwhelmingly to the poor and young people who cannot afford to buy houses.

The professional class in these metro areas is strikingly similar to the old extractive elites of Agrarian regimes. For both of those classes, their primary source of wealth comes from owning very expensive land and government policies that drive up the value of those lands. While they each use different methods and the old elites were far more deliberate in their extractions, the results are the same.

Both groups are what economists call “rentiers.” Rentiers are persons who gain wealth, not by creating it, as people who work in free markets do, but by extracting wealth created by others. Government policies are what enable them to do so.

Henry George’s solution

To solve the problem, Henry George advocated a land value tax. A land value tax is similar to a property tax, except that it only taxes the value of the land. Land value taxes do not tax the value of any buildings on that land. The logic behind George’s proposal is that landowners did not create the land, but they did create the buildings on that land. George believed that we should not tax productive assets created by human beings, only land created by God.

While a property tax seems similar to a land value tax, it creates radically different incentives for landowners in or near metro areas. Currently, a landowner has a strong incentive to hold onto empty plots of land as long as possible to get the maximum possible amount of money at the point of sale. They can do this because their property taxes are relatively low.

The land value tax, however, gives landowners a strong incentive to develop or sell their empty plots of land. If landowners decide to lease their land, they have the incentive to develop the land as much as possible to maximize their returns. The more the development benefits society, the more valuable the land becomes, so the incentives of the landowner are aligned with societal interests.

What is even better is that increasing the value of that single plot of land will also increase the value of the surrounding land. So, if a metro area has a high-value-added export industry that creates wealth for the city, landowners will have a strong incentive for building the infrastructure to house workers for that industry and others. This will increase the value of the land and the taxes raised from that land.

In the Decentralizing Political Power chapter of my book, I made the case for radical decentralization of political power from federal government to the state governments and the creation of new states. If this were implemented, this would require a massive new funding source for states to fund programs that are currently being run by the federal government.

I believe that this new tax should be a land value tax. While most taxes directly or indirectly undermine progress by taxing productive wealth or income, the land value tax creates incentives to build infrastructure that helps to create progress. This makes a land value tax far superior to property taxes, sales taxes, state income taxes, and state corporate taxes.

Ideally states would abolish all their state and local taxes, except for user fees, and replace them with one, simple land value tax. Less radical would be to replace current property taxes with land value taxes that raise a similar amount of revenue.

An even much more targeted strategy would be to replace the current property tax with a land value tax in states and metro areas that have an Affordability Index of over 4. This would mainly be in states in the Northeast and Pacific coast. Implementing a land value tax would not immediately lower housing prices, but it would give a strong incentive for landowners to construct some sort of housing on their land.

There are good reasons for liberal Democrats to favor a land value tax. They want a progressive tax system that taxes high-income earners at a higher rate than either the middle class or the poor. They also want to tax wealth.

Most proposed wealth taxes are completely unworkable because most wealth is so mobile. A sizable wealth tax would only drive capital out of an area, causing the economy serious damage. Land, however, is a unique source of wealth that is not mobile. And the total value of land is highly concentrated.

There are also good reasons for conservative Republicans to favor a land value tax. Republicans have long wanted to decrease or eliminate income taxes, property taxes, corporate taxes, and sales taxes. They are also opposed to taxing the kinds of wealth and income that generate economic growth. Land value taxes give them an option to do so.

Republicans might also enjoy the fact that the increased tax bill would be largely paid by property owners in the wealthy neighborhoods of metro areas in the Northeast and Pacific coast, all of which are liberal strongholds. Rural and metro areas in the Midwest and South would see little change in their tax rates. If liberals want to increase taxes, conservatives might say, let them pay the bill themselves.

In general, there is a pretty close association between geographical areas that want a more expansive welfare state and those areas that have over-priced land. It makes sense to tax that land to pay for these expansive social programs. Land value taxes in other geographical areas would generate fewer revenues, but those areas also tend to have less of a desire to tax and spend in the first place.

I believe that the combination of a land value tax, the abolition of urban containment zones, and a radical streamlining of zoning and building codes would have a profound effect on land usage in and near major metro areas. Landowners with empty lots, lightly developed or agricultural land would have a strong incentive to develop it. And they would have a strong incentive to choose the types of development that are most valued by society. In particular, empty lots on the outskirts of metro areas would be rapidly developed.

Granted, it will take a long time for the price of land to fall enough so that housing becomes affordable in the major metro areas in the Northeast and Pacific Coast. However, in combination with domestic migration to more affordable cities, particularly by youths, we can mitigate the problem quickly and bend the housing curve to greater affordability.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

Can a Land Value tax make housing affordable? (this article)

While there are practical limitations to LVT, all taxes have limitations. LVT is simply the “least bad” of many alternatives. Imagine a future of semi-sovereign charter cities. They raise revenue primarily via LVT with no deadweight loss, no burden on incomes, and affordable housing.

Further, with LVT, the incentives are properly aligned…to raise more revenue, the government must raise land values (not tax rates). Doing so requires policies that make the charter city a place people and businesses want to be in. How cool is that?

Instead of extracting wealth, the goal becomes to create more and more of it.