The Second Key to Progress: Trade-based cities packed with a large number of free citizens possessing a wide variety of skills. These people innovate new technologies, skills and social organizations and copy the innovations made by others.

Wealthy nations currently have very high urbanization rates. They also have robust infrastructures in the domains of water, sanitation, electricity, transportation, communication, police, and fire. On the face of it, it is difficult to see how the issues addressed by the second Key to Progress could be improved.

One very bad trend within cities in wealthy nations, however, is unaffordable housing. Affordable prices are one of the key foundations of prosperity. Nowhere is this truer than in housing.

In general, change in per capita GDP is a useful high-order measurement of progress. Per capita GDP measures the amount of money that people have, but what is far more important is what people can buy with that money. Affordable prices, particularly for necessities, are also a key metric for measuring progress. Nowhere is this more important than housing. Without housing, cities simply cannot exist.

Most of the following is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

his post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

How housing became unaffordable (this article)

The Importance of Affordable Housing

Housing is crucial to people’s overall standard of living, because it takes up such a large portion of their budgets. According to the Consumer Expenditure Survey in 2019, the typical household spends around 19.3% of their spending on mortgage or rent. They spend another 13.5% on other housing-related expenditures, such as utilities, maintenance, and furnishing. In all, just under one-third of a typical household budget is spent on housing. This is far more than any other category (CES).

Housing prices particularly impact lower and middle-income households. Low- and middle-income households spend a significantly higher proportion of their income on shelter than upper-income households. Households in the lowest 10% of income spend 25.8% of their income on mortgage or rent, while the top 10% spend only 17.7%. Middle-income households range between 19 and 23%.

This figure understates the significance of housing to monthly budgets. Many retirees have paid off their mortgage, so, for the remaining citizens, housing makes up a higher proportion of their spending. Some people are still paying off a mortgage for a house that they purchased when housing prices were more affordable, but many have bought more recently at higher prices.

Housing Affordability Before 1970

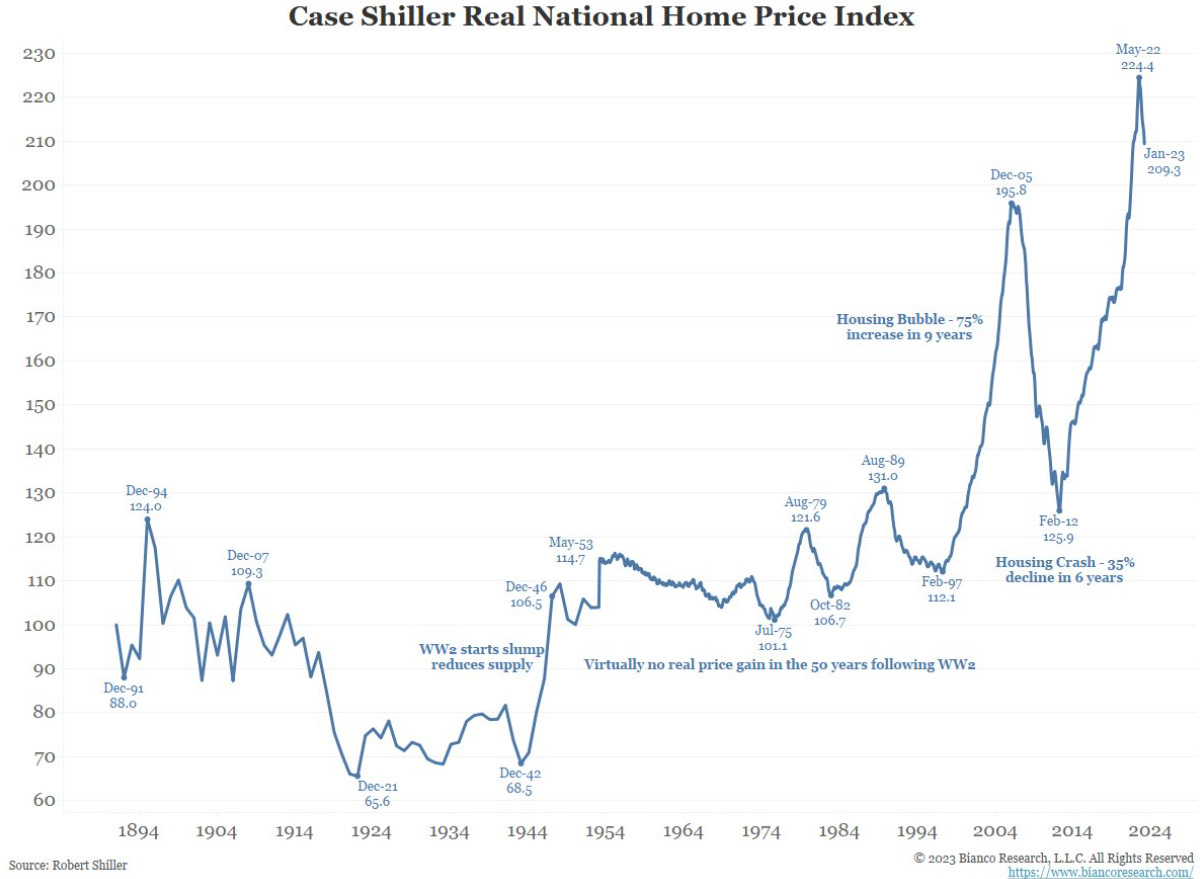

Housing inflation is a relatively new phenomenon. Until 1970, housing prices did not vary much from the core rate of inflation. This made housing affordable across the nation.

A useful means of measuring housing affordability is the ratio between the median cost of a house and the median family income within that metro. In 1969, virtually every metro in the United States had a ratio of 3.0 or less. The national average was 1.8 (Antiplanner, 2020). The below graphic is based on average earnings, rather than median, but it gives a pretty clear historical trend.

At that point, housing in the United States was affordable everywhere, even in the wealthiest cities. Though we do not have good housing price data from before that time, there is every reason to believe that this had been the case throughout American history.

Then, in the 1970s, something began to change radically. In a few key metro areas, housing prices began to increase far more rapidly than median family incomes.

The affordability numbers were quite similar in Europe, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. It was partly down to simple supply and demand. When the population grew in a metro area, builders built more houses. And they typically built single-family residences on the outskirts of the metro area, where land was relatively cheap. Housing prices would vary with the level of income for the metro, but housing affordability would stay roughly the same.

Failure Since 1970

Government policy over the last 50 years has been an abysmal failure at promoting affordable housing. In fact, government policy has been extremely effective at making housing unaffordable in many metro areas.

Since the 1970s, many metro areas have experienced inflation of housing prices that have been far beyond the base rate of inflation. More accurately, it is an inflation of the price of land under those houses. The actual houses themselves are not increasing in cost at anywhere near the rate of land prices. Almost all geographical variation in housing prices is due to the price of land, while variations in labor and materials are not very large in comparison (Antiplanner, 2020).

People living in these metropolitan areas take it for granted that home values will continually move upward, as if by magic. Few stop to think about what causes this inflation. Far more people just enjoy the rapid increase in their wealth that is a result of this land inflation.

This has led many urban areas to have far less housing than their local demand. At the current housing construction rate, it will take decades to make up the difference and the population will likely increase in the meantime.

This housing inflation has impacted the large urban areas of the Northeast and Pacific coast of the United States, Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Housing inflation has become such a part of modern life that we take it for granted as if it is normal. It is anything but normal. It is caused by very bad government policies.

New Deal Democrats Promoted Sprawl

Today, “sprawl” is perceived as a bad thing, particularly by those on the Left. Sprawl is typically defined as the spreading of urban developments onto undeveloped land near the city. This trend is almost universally derided by those on the Left as a bad thing that undermines our quality of life and our natural environment. Promoting density and limiting sprawl is now considered one of the most critical goals of urban design.

Ironically, we forget that it was Democrats who actively promoted the very suburban developments that are so derided today. In the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, New Deal Democrats actively promoted home construction and ownership on the outskirts of urban regions. They also founded institutions – the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Fanny Mae, and Freddy Mac – that made it easier for working-class families to purchase those homes. The federal government allowed (and still allows) workers to deduct the interest on their mortgage payments from their taxes. This is a substantial stimulus on home ownership. Most importantly, the federal, state, and local governments erected few barriers to building homes.

These policies were particularly important because America was experiencing a post-war Baby Boom. All these new families needed someplace to live, and new housing construction on the outskirts of metro areas was deemed the best solution to the problem.

During the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, the suburbs popped up like mushrooms in the forest. The result was a fantastic increase in the standard of living of the American working class from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. Certainly, a growing economy, strong trade unions, and limited foreign competition played important roles, but one should not underestimate the importance of affordable housing.

Rather than being cramped up in small, urban apartments, young working-class families could buy new, much larger single-family residences in brand-new suburbs. The government encouraged suburbanization by constructing new freeways to make transportation to and from those suburbs easier, faster, cheaper, and safer.

Integration of Ethnicities in Suburbs

Suburbanization played a key role in promoting ethnic and religious integration. World War II and the following post-war economic boom witnessed a profound change in the geographical dispersal of American ethnic groups. Before World War II most ethnic groups were highly concentrated geographically.

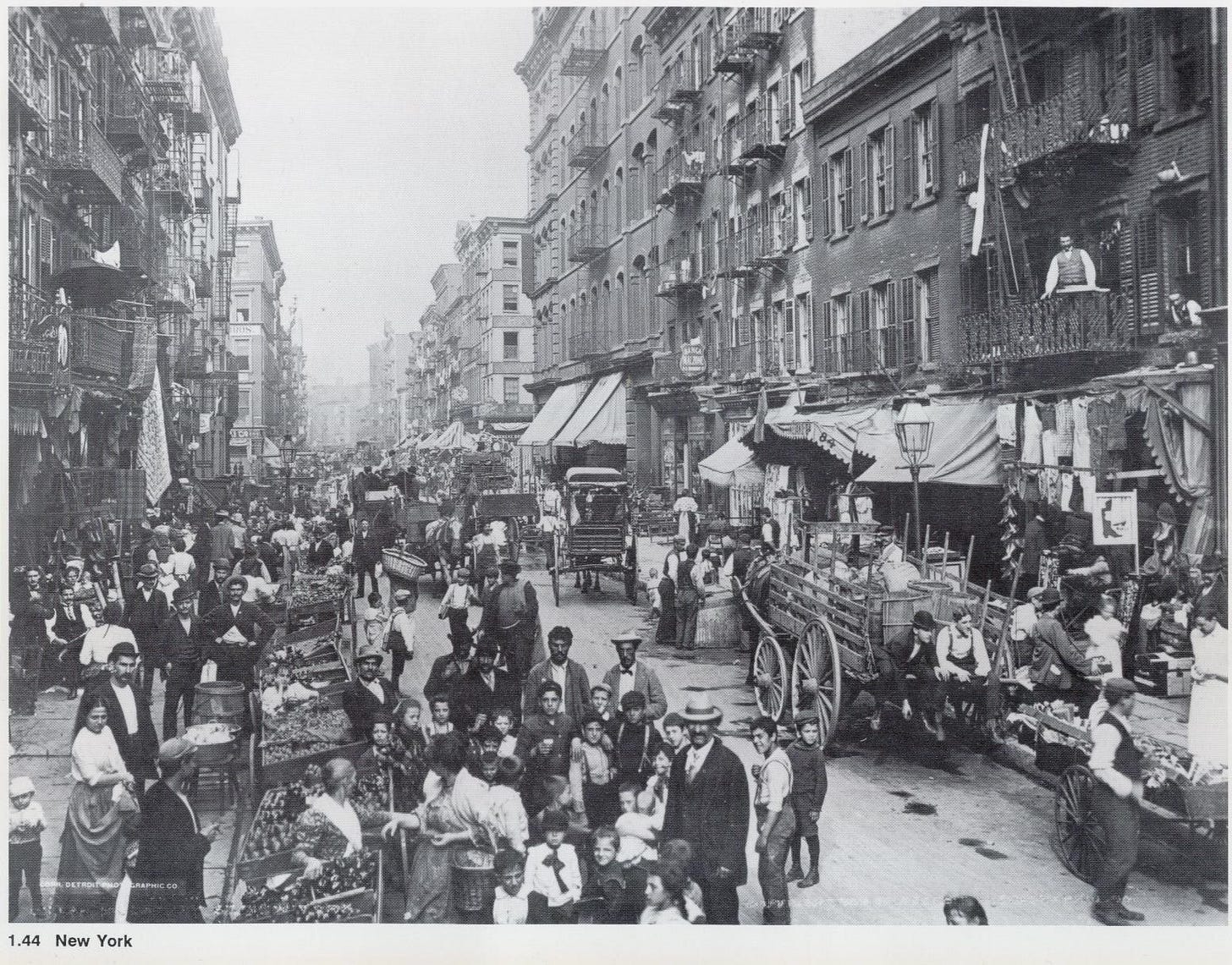

Today many people think of Americans as being divided up into four large racial groups: Whites, Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics. Before World War II, however, most people outside of the South thought in terms of ethnicities and religions, rather than race. There were no White Americans; there were Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, German Americans, Norwegian Americans, Polish Americans, and Irish Americans. Outside of the Deep South, people did not even think in terms of race. Each of these ethnic groups was heavily concentrated geographically.

Northern New England had a British majority with a strong French-Canadian minority, particularly near the Canadian border. Southern New England had a British majority with a strong Irish Catholic minority in the cities. And each neighborhood was clearly either British or Irish. Few lived in the “wrong” neighborhood.

The New York City region was even more divided. While one might look at the overall composition of the city and declare it “diverse,” any individual neighborhood was nothing of the sort. A neighborhood was either British, Italian, Irish, Black, Jewish, or one of the dozens of other ethnic groups that lived in the region. At the national level, America was extremely diverse. At the regional and neighborhood level, America tended to be ethnically homogeneous.

The rural regions stretching westward from Pennsylvania through the Middle West were heavily German. The northern tier of the rural Midwest was heavily Norwegian, Finnish, Swedish, or Danish. The industrial cities of the Midwest were similar to New York City with a wide variety of ethnically homogenous ethnic groups, primarily from Eastern Europe. The only region that was stratified by race was the Deep South with its classic White/Black divide.

Just as important, many of these ethnic groups were divided internally by religion. This was particularly true of the two largest minorities: the British and Germans. Americans of British descent often identified themselves as Methodist, Baptist, Mormon, or Episcopalian. Germans were divided into Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. Each group kept to themselves socially and rarely socialized outside their religious group.

What this effectively meant was that ethno-religious groups were highly segregated until World War II. If those levels of ethno-religious segregation had continued during the post-war economic boom, it would have produced great inequalities between groups.

Ethno-religious groups living near factories would have prospered, while those living far from the factories would have missed out on much of the progress. The massive amounts of construction of single-family residences on the outskirts of growing metro areas ensured that this did not happen.

After World War II, young families from previously ethnically-segregated neighborhoods in the cities moved to brand-new houses in the suburbs. All the people from those segregated urban neighborhoods suddenly lived together in the same suburban neighborhood. Not surprisingly, many of them fell in love with each other, got married, and had children. After a few generations of this process, ethno-religious diversity and segregation among whites melted away. Just as important, those young families enjoyed the benefits of strong economic growth.

Genetic and cultural mixing meant that all these ethnic and religious minorities fused until they became what we now call “Whites.” American unity and integration were stronger than ever. Without the growth of the suburbs, ethnic and religious segregation would have persisted.

Tragically, in most parts of the country, Blacks were left out of this process of integration, so legal and cultural racial segregation remained (while Asians and Hispanics were still relatively small in number). Only with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, did racial segregation in housing begin to diminish.

For all Americans, though, the period between World War II and the early 1970s was one of widely-shared prosperity. Affordable housing played a key role in that widely-shared prosperity.

Housing Is Both a Product and an Investment

Housing is unlike any other type of market. In most markets, if prices become more affordable, everyone benefits (except for producers). In housing, however, prices are more of a zero-sum phenomenon. Some people benefit from affordable housing, while other people lose (at least in comparison to the current situation).

Housing is unusual because it is both a consumer product and an investment. Most products that you buy on the market depreciate rapidly after the initial purchase. This makes them extremely poor investments.

When a person buys a home, however, they are not only purchasing a place to live. They are also purchasing an investment that can potentially accrue more value over time. For many homeowners, their house is their most substantial investment. For some, it is their only investment.

This places the financial interests of homeowners in direct conflict with those who do not own homes. When the price of housing goes up, rents go up with them. So renters have to spend an increasing portion of their income on rent. Aspiring homeowners also have to save up a larger deposit and pay higher prices for the same house. Meanwhile, homeowners are making money (though, of course, they do not fully realize the increased value until they sell their house).

When housing prices stay affordable, homeowners fail to gain wealth from their most important investment. While renters and young people need affordable housing, homeowners want a steady upward trend in the value of their houses. Such a situation is vulnerable to political influence.

Urban Containment Zones

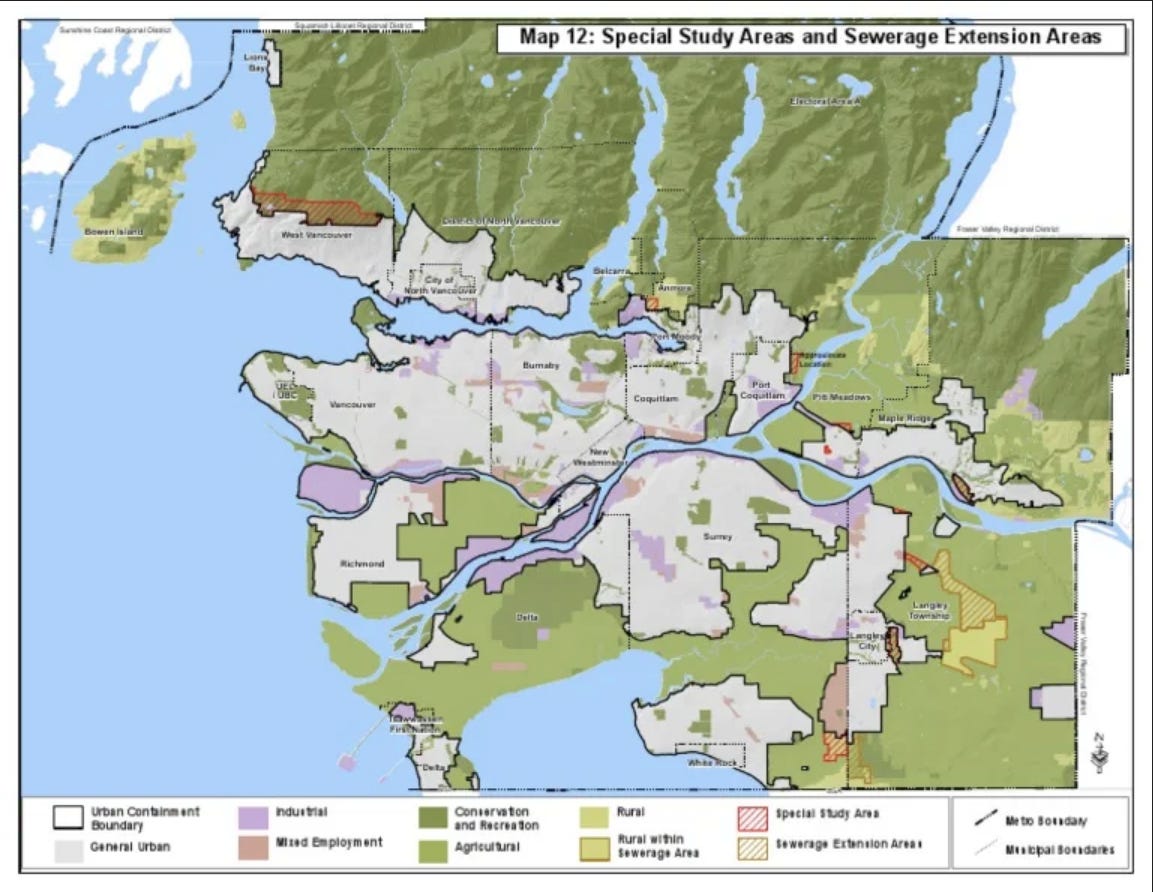

Take a look at a list of metro areas that have seriously expensive housing in the United States: San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, San Diego, Portland, Seattle, Boston, New York City, and Washington DC. All of these cities have two things in common: robust economic growth and urban containment zones. Most people are very aware of the first factor, but they have never even heard of urban containment zones.

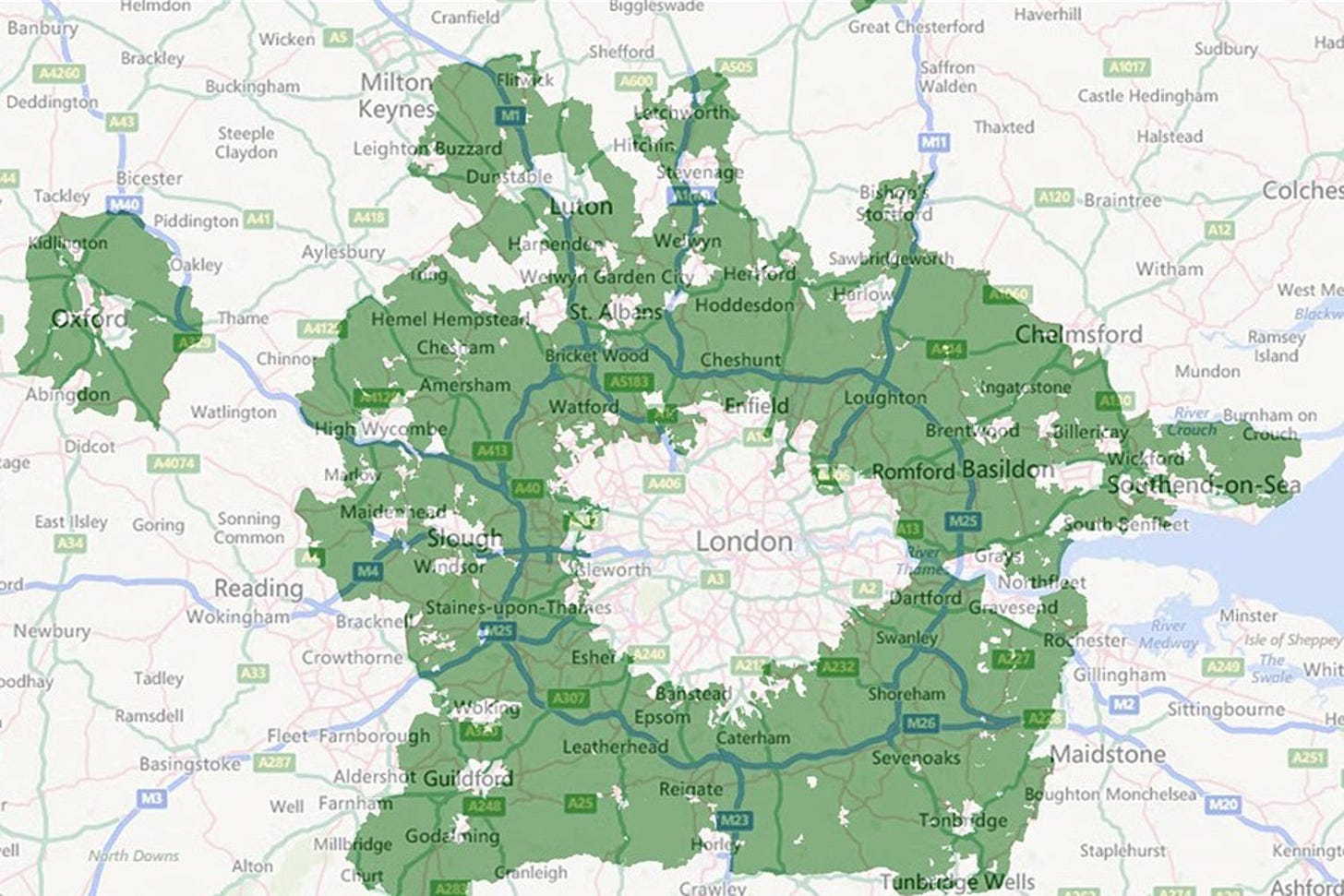

Urban containment zones (sometimes called “green belts”) are areas immediately adjoining metro areas where builders are placed under serious restrictions on building new homes. Often these zones completely encircle entire metro areas, effectively prohibiting builders from expanding outward as demand for housing increases. Sometimes urban containment zones work in conjunction with natural geographic barriers, such as oceans, lakes, or mountains, to have the same effect.

Ironically, the walls that surrounded cities during the medieval period have been reconstructed as green walls today. While these green walls are pleasant respites from urban congestion for a lucky few who live near them, the negative consequences for the rest of society are massive and widespread.

The world’s first urban containment zone was created in London in 1947. The area immediately outside the edge of the London metro area is called the Metropolitan Green Belt. The idea spread rapidly through the community of urban planners because it appeared to protect natural habitats and farms while having no costs to society.

Hawaii enacted the first urban containment zone in the United States in 1961. The state designated all land in the state as either urban or rural. Land designated as rural had serious restrictions on development enacted.

In 1963, California enacted strict growth-management laws, followed rapidly by Oregon, New Jersey, Maryland, Washington, and all the New England states. Florida did the same but then repealed those laws in 2011. Some cities, such as Minneapolis, Denver, and Salt Lake City did so at the local level. In total, about 45% of the nation’s population lives in cities or states with strict growth-management laws (O’Toole, Eicher).

Take a look at a satellite photo of any of these urban areas. You will notice very abrupt changes between dense urban development and green, blue, or brown areas with very limited development. Sometimes this will be due to oceans, lakes, or mountains, but often it is not. This is the urban growth boundary. An example is in the photo above.

The long-term negative consequences that these laws created for housing affordability as the economy grew were hidden for decades. Now, everyone can see the symptom of the problem, unaffordable housing, but they cannot all see the cause of the problem itself.

Of course, having parks and wildlands in and near urban areas is a valuable amenity. No one, least of all myself, wants to do away with them. The issue here is not whether cities should have parks and wildlands. Of course, they should.

The issue is whether we should deliberately construct green walls to entirely encircle urban areas and cut off all future home construction on the outskirts of metro areas. The greenery of these belts was an accidental side-effect of the main urban planning goal; to build walls around cities outside which houses cannot be constructed.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

A lot of the issues of housing can be solved by implementing a Land Value Tax and reducing property taxes. Taxing land more heavily would:

1) Reduce the purchase price of land

2) Force land use to be productive (fewer parking lots and golf courses)

3) Remove the punishment that developers received when build housing

It's like that tax reform would naturally force land use and zoning reform and allow more housing to be built to meet demand.

Didn’t the car industry have a lot to do with sprawl? I’ve heard lobbying pushed development outward to rely more on roads. I think a lot of issues society faces regarding cost of living would be solved by designing a more walkable society.