Nations that experienced transformative economic growth

The list is longer and goes further back in time than most people realize

In this article, I examine nations that have experienced long periods of sustained economic growth. Some of these examples are quite famous, while others are not so well known.

I will use a few rules:

The data comes from Angus Maddison’s estimates of per capita GDP going back to the year zero (!). Given that they are estimates, they are subject to error, but for our purposes, the error is not big enough to matter.

The geographical regions for Maddison’s estimates correspond to present borders, not the borders at the time. Therefore, we must supplement the data with our knowledge of the region at hand.

The frequency of estimates varies greatly by how far one goes back in history. After 1830, the estimates are for each years, but they are far less frequent in earlier eras.

I look for long periods of growth, typically over 20 years without a downturn.

I exclude Western Europe after World War II, as this is a well-known case that swamps all the other examples.

I also exclude Middle Eastern nations whose economies were dominated by energy exports.

I calculate the average growth rate with a simple total growth divided by the number of years, which is not accurate, but it is a good ball-part figure.

So let’s get started.

Economic growth before 1000

Zip. Zero. Nada. (Well, maybe Ancient Greece was an exception).

The roughly 100-200,000 years before the year 1000 CE (or what historians used to call AD) have no evidence of economic growth that benefitted the masses. Every society was stuck at or near subsistence levels (roughly $450 income per year). The only way to get ahead was to steal from others through forced taxes or military conquest.

Depressing, but true. This sad state of affairs should always be our point of reference.

Early Commercial societies (1000-1500)

Some time after 1200 things began to change. Unfortunately, the period between data points in Maddison’s estimates is very long. Maddison made estimates for the year 1000 and then again for the year 1500. For virtually the entire world, the estimates are almost identical. Every society but two (Northern Italy and Flanders in modern-day Belgium) was stuck at subsistence levels (roughly $450 income per year).

To be clear the regions that Maddison uses are actually the modern borders of Italy and Belgium. Given that we know from the historical record that Northern Italy was much wealthier than Southern Italy and that Flanders was much richer than Wallonia, it is fair to say that the regions “Italy” and “Belgium” actually correspond to Northern Italy and Flanders. Both were Commercial societies.

We also know from the historical record that Northern Italy started growing first (probably sometime after 1200), and then Flemish growth was much closer to 1500. Northern Italy invented modern progress, and Flanders copied the Northern Italians.

Note that the economic growth of these two societies was excruciatingly slow by modern standards, less than one-third of one percent between 1000 and 1500. This level of economic growth, however, was stellar compared to all other societies up until that time. Given that the historical record is clear that economic growth in both societies started well after the year 1000 (particularly for Flanders), economic growth rates were likely close to one percent per year.

Late Commercial societies (1500-1820)

Now we are looking at what we might call modern pre-industrial economic growth. A few more societies added themselves to the list of nations that experienced material progress. All three were Commercial societies.

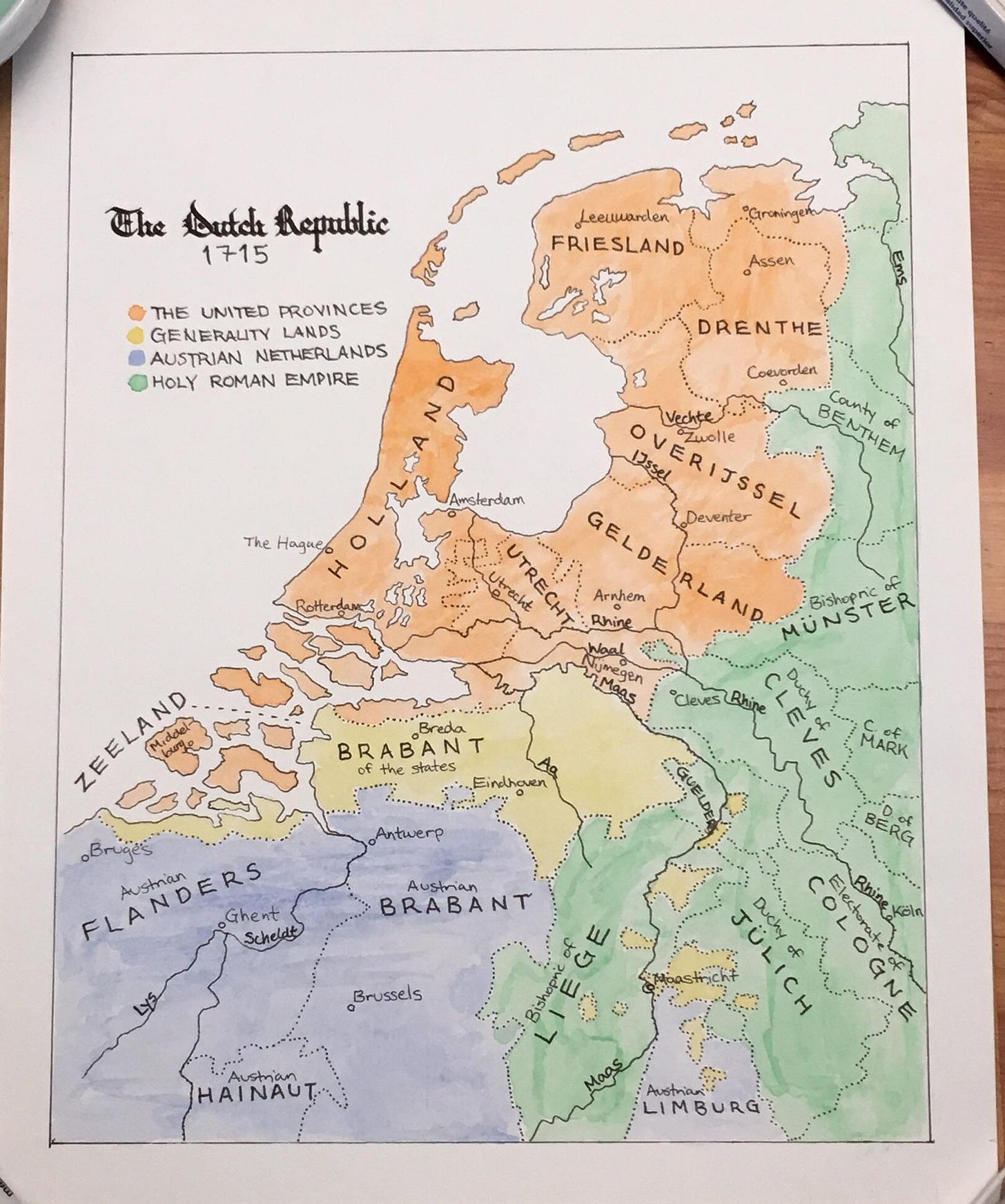

Netherlands

The rates of economic growth in the Netherlands between the years 1500 and 1700 were stellar (close to 1% per year). This was during the height of the Dutch Republic. Given that the Dutch were waging a war for survival with the Spanish Empire, this is quite extraordinary. And then after 1670 the Dutch were engaged in a struggle for economic survival against the French and British empires. The Dutch lived in a tough neighborhood.

It seems quite likely that the Dutch Republic in the late 17th Century had the highest standard of living of any pre-industrial society (estimated at $2130). Even today, there are about 40 nations with lower levels of economic development!

Pre-industrial England

Now we come to pre-industrial England. I say England, instead of the United Kingdom, because southeast England was far richer than the rest of the British isles. The exact period when the UK industrialized is one of the most controversial topics in economic history, but I think one should note that British economic growth did not show a major uptick until the 1840s (during and a little after the railroad boom).

Economic growth from 1500 to 1840 was a smooth upward trend with overall levels of economic growth at 0.43%. There were breaks in economic growth for the English Civil war and the Napoleonic wars, but there were no signs of increased economic growth anywhere in this period. This does not mean that the famous textile boom of the 18th Century did not matter, only that it did not change overall rates of economic growth.

As I see it, Britain from 1500 to 1840 was a Commercial society that:

Experienced economic growth that was no greater than previous Commercial societies (Northern Italy, Flanders, and the Netherlands)

Its “bleeding edge” technological innovations were automating textile production using water power. This was merely the next iteration of highly productive textile industries based on water and wind power that had previously existed in Northern Italy, Flanders, and the Netherlands.

As of 1820 the textile industry was still not large enough to fundamentally change the trajectory of national economic growth. Economic growth rates in the 1820s were not substantially different from the 16th Century.

Coal was still mainly used for home heating. Water, wind, and animal power were still the dominant energy sources until the invention and scaling up of the railway.

Coal, though critical to later economic growth, was still a very labor-intensive industry.

Pre-industrial America

In some ways, the per capita economic growth of British North America and the early United States was even more impressive than England’s growth. American per capita economic growth rate was:

higher than any prior nation and

its overall population was growing at a phenomenal rate due to high birth rates and high levels of immigration.

It is important to note that American economic power was well in evidence long before the Industrial Revolution.

The UK industrializes (1842-1856)

Now we come to industrial Britain. While most economic historians would claim an earlier starting date, most agree that the industrialization of Britain is where modern economic growth began. The industrialization of Britain is clearly one of the great breakthroughs that spread progress throughout the globe, I believe, however, that Britain accelerated progress that was already in existence rather than starting it.

I think most economic historians understand this, but they have not fully integrated that fact into how they present modern economic growth. Most economic historians see:

Pre-industrial societies

Industrial societies with the Industrial Revolution in Britain being the critical dividing line.

My view on history is that there were three phases:

Agrarian societies (along with other society types outside Europe)

Commercial societies which invented human material progress

Industrial societies, which radically accelerated progress and spread it to regions where it was impossible with pre-industrial technologies, skills, and organizations.

Getting back to Maddison’s estimates, starting around 1842 British economic growth suddenly increased from less than one percent growth to over three percent growth. That is more than triple the previous rate. Those growth rates were sustained for the next 17 years.

While the British economy slowed down after 1852, British growth rates remained well above pre-industrial rates for generations. This period of British history was a radical transformation largely caused by the innovation of new technologies that applied fossil fuels to transportation, agriculture, communication, and manufacturing.

I am going to be writing much more on the Industrial Revolution in Britain, so I will say no more here.

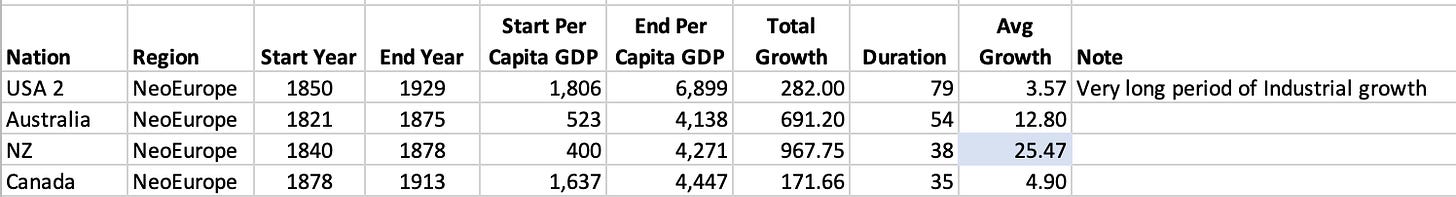

The Anglo world industrializes

One of the most underestimated economic transformations in history was the:

Migrations to colonies within the British empire

Industrialization of the Anglo world.

Of course, American industrialization gets all the focus, but Australia, New Zealand, and Canada were fundamentally transformed as well. Though much of it was driven by the expansion of pre-industrial technologies, such as agriculture and services, these nations experienced even stronger economic growth than industrial Britain.

And when combined with mass migration from Europe, industrialization helped the United States transform into a global economic and military Super Power.

Continental Europe industrializes

Now we come to a bevy of smaller European nations that industrialized soon after the United Kingdom. Note they were dominated by societies that had earlier been either Commercial societies or Free Peasant societies. Germany is the only former Agrarian society that experienced rapid economic growth in the 19th Century and that did not occur until after 1880.

Note that after World War II almost all Western European nations experienced rapid, sustained economic growth. During that period, however, there are no nations that really stand out for their levels of economic growth, except West Germany from 1946 to 1973. It was truly a regional economic growth, perhaps for the first time in world history.

I am also including Spain and Ireland on this list, both of which were on the periphery of Western Europe and industrialized after World War II.

Much of Asia industrializes

Now we come to the industrialization of Asia. This economic growth really comes in three phases:

Japan and Hong Kong starting in the 1870s and and continuing until World War II.

Japan and the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea) starting at various times in the decades immediately after World War II.

A much larger take-off in the more populous Asian nations (China, India and Indonesia)

The third phase was something like the regional growth rate of Western Europe after World War II. This growth occurred to one extent or another in most nations in East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, though China, India and Indonesia were the most important.

Note: I did not include economic data in this study after 2008.

A few other fast growers

There are also a few geographical outliers that do not quite fit the mold. Each story was impressive in its own right. Most of them have received very little attention from economic historians. Botwana’s economic growth is particularly impressive because the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa has been noticeably missing from the list of fast-growing economies.

Nations that experienced temporary growth

There are also several nations, primarily in Latin America, that experienced:

Strong long-term economic growth

Followed by long periods of stagnation or decline.

Each nation’s economic growth rates were very impressive in their day, but they each failed to permanently transform their economies as Europe, North America, and East Asia has.

A few observations

Long-term economic growth did not start with the Industrial Revolution. It started in Northern Italy sometime between 1000 and 1500.

That economic growth then spread to Flanders, the Netherlands, and England.

The economic growth rates of pre-industrial Commercial societies appear to be close to one percent. This is slow by modern standards, but extremely fast by pre-industrial standards.

The Netherlands 1500-1700 likely had the longest and strongest sustained growth before the Industrial Revolution.

UK 1842-56 had much faster growth (3+%) than any previous economy; this period can be considered the high point of the Industrial Revolution. Before 1842 UK growth was strong but nothing unusual compared to previous Commercial societies

The rates of economic growth have increased dramatically over time. Particularly in Asia since 1990. double-digit growth rates have not been unusual. This is presumably because the distance to catch up with the leading economy increases over time, as well as the ability of trailing nations to copy lead nations.

Rapid economic growth is highly regional. Economic growth started in Northwest Europe, shifted to regions settled by Europeans, and then East Asia.

Each region had a “lead dog” that started regional economic growth:

Northern Italy, then the Netherlands, and then the UK in Northwest Europe

USA in North America

Japan in Asia.

Based on early growth rates in India and Indonesia, South Asia and Southeast Asia seem ripe for very strong growth in the upcoming decades.

Nice compressed history lesson. It seems political, economic, and technological threads are interweaved from the 1500's to the 1880's in ways that are difficult or subtle to unravel and explore as separate influences/ concepts. And given the comments about Germany, Ireland, and later European and non-European growth, we have to keep our wits about us to understand that the mass benefit results you are exploring did not spring up everywhere as rapidly as our modern news cycle and internet exposure might influence our thinking. A lot of social and physical infrastructure (and human and money capital) has to be established to get these things off the ground in a major way.

Having been born in St. Louis, I was surprised to see the USA map for 1820 showing such a concentration of population around that whole area. It seems it was an even earlier and larger springboard for settlers going North and West from there than I had appreciated. I had left the state long before they built the Gateway Arch so maybe I would have learned more details of that historical contribution if I had been local when it was built.

Per Ober, the classical Greek merchant city states such as Athens were as prosperous as Golden Age Holland with extremely high population densities, and this lasted for centuries. Goldstone suggests Song China and Tokugawa Japan also qualify.

I think Goldstone's term "efflorescence" of notable pre-IR escapes from Malthusian forces captures this better than “progress." Obviously a gray line separates the two concepts, but Goldstone also suggests that fossil fuel energy is the distinguishing factor, with Holland being an especially interesting border case due to peat.