I have written several articles about Commercial societies. My focus so far has almost entirely been on the city/states of Medieval and Early Modern Europe in:

Northern Italy (roughly 1200-1500)

Flanders (roughly 1400-1550)

The Netherlands (roughly 1500-1800)

Pre-industrial England (roughly 1500-1800)

Already several readers have asked me about the city/states of Ancient Greece.

So far, I have deferred to giving a clear answer because I did not feel that there is enough economic and demographic to give a clear-cut answer. Fortunately, one of my readers mentioned that I should read The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece by Josiah Ober, which is part of the excellent Princeton History of the Ancient World series. The book is the best overview of Ancient Greek economy that I have seen, so I am ready to take on the question: “Were Ancient Greek city/states Commercial societies?”

Some very strong similarities

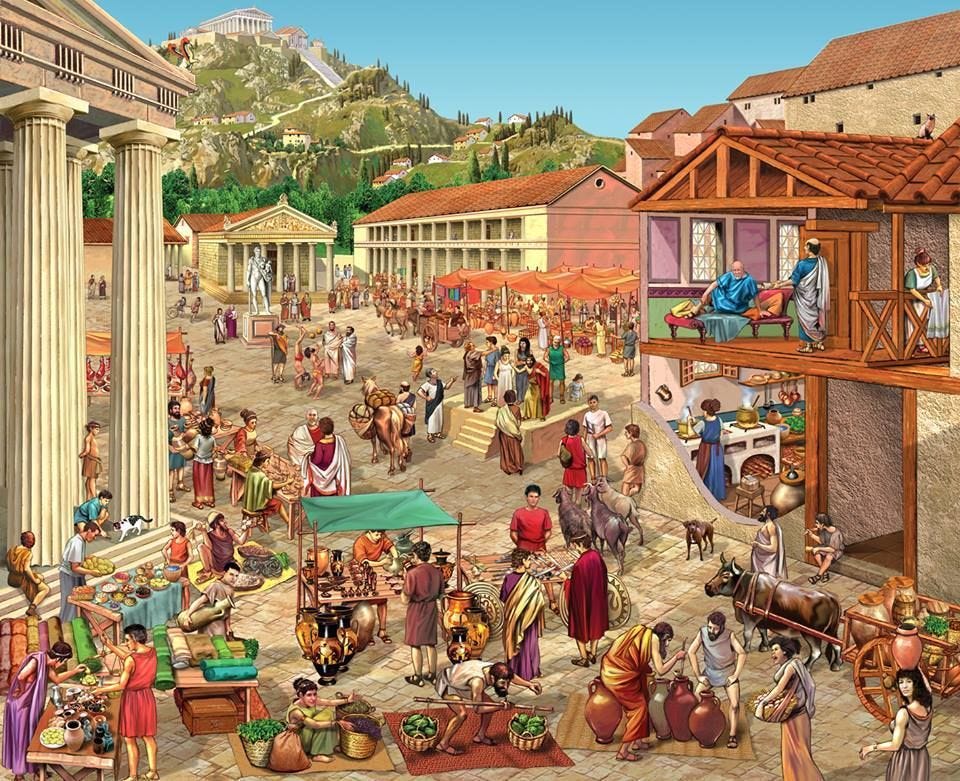

Leaving aside the definition itself, it is very clear the Ancient Greek city/states had strong similarities to later Commercial societies. By the Classical period the Ancient Greek city/states:

Were highly urbanized compared to other societies at the time, though it is not clear how much.

Had decentralized and market-based economies for many goods, including food.

Had a decentralized political structure that included elected officials and direct democracy.

Had a diversity of competing religions, or at least Greek Gods that had their own worshipers

Had dynamic export industries in silver, olive oil, wheat, and other goods.

Had citizen militias and navies

Had large numbers of immigrants, though most were ethnic Greeks

Had an incredibly dynamic society in art, philosophy, science, history, and just about every field of intellectual inquiry at the time. Indeed, the Greeks virtually invented most of those fields.

It would also be very convenient for me to claim Ancient Greek city/states as Commercial societies as those societies are widely believed to be the originators of Western culture. If my theories can explain those extraordinary dynamic societies, then it makes my theories even more enticing.

Defining Commercial societies

Let me start, by reviewing my working definition of the Commercial society. First of all, the concept of a Commercial society goes back to the Scottish Enlightenment. Much of their work, particularly in economics, was specifically to understand the inner workings of their own society, as well as England.

The ultimate outcome was Adam Smith’s masterpiece “The Wealth of Nations.” This book is widely considered to be the beginning of modern economics (or more accurately “Classical economics.”).

As far as I know, Adam Smith and other members of the Scottish Enlightenment never strictly defined the term “Commercial society” so that a specific society can be categorized as either a Commercial society or not. That is why I created my own definition based on how humans acquire food calories. The idea of linking society types to food production was common in the 19th Century (Henry Home, Edward Burnett Taylor, and Lewis Henry Morgan) and well into the 20th Century (Julian Seward and Gerhard Lenski), so I think that I am only on solid ground with the following:

Commercial societies are a type of society that:

Produces the majority of its calories from people selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the marketplace.

Without widespread use of fossil fuels (which differentiates it from modern Industrial societies)

There is absolutely no evidence that Ancient Greece widely used fossil fuels, although they did invent Greek Fire as a weapon of war. So that leaves how people acquire their food.

Reasons for my hesitancy

My biggest concern with Ancient Greece being a Commercial society was the:

Productivity of its agriculture

Its widespread use of slavery

I already have an article documenting the very low productivity of Ancient Farming practices. Ancient Farming practices were roughly 50% as productive as Medieval Farming practices and 25% as productive as Commercial Farming. That would leave very little food surplus for feeding cities.

There are very clear historical records of grain imports in Ancient Greece, particularly from the Black sea, but it is not clear what percentage of their total diet came from those imports. And it is not clear that other regions could have generated much of a surplus for the exact reason that the Greeks could not.

Slavery is closely related to this issue because it is often thought that Classical slavery was a way to overcome the low productivity of agriculture by having adult male slaves work hard in the field while not having to support wives and children. The adult male slaves are essentially the same as domesticated animals that work in the field, such as horses and oxen.

I think the question comes down to:

How urbanized was Greek society?

How market-based was food production and consumption? And since wheat, barley, and olives/olive oil were by far the largest source of calories, we are basically talking about the trade in those products.

Were the average citizens wealthy enough to afford to buy their food in the marketplace?

If Greece was very urbanized, then we know that they got their food from somewhere, and it seems unlikely that all the citizens of the cities trudged out to the field every day (although perhaps their slaves did). The use of horses and horse-drawn wagons was not common in Greece, so walking was likely the only means of transport. There is only so much food that Ancient Farming practices could have grown within walking distance of cities.

The second question goes along with the first. Ancient Rome had government imports of wheat from the Nile river to the city of Rome, and likely other major cities. That enabled the city of Rome to grow to a population of about one million. I have read no evidence of similar government-sponsored wheat distribution programs in Ancient Greece. So urbanites must have purchased the bulk of their calories on the market.

The evidence

Acquiring solid economic and demographic about a society that disappeared almost 2500 years ago is not easy. I believe that Josiah Ober’s The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece is the most thorough analysis that we have so far. Ober concludes:

“The ancient Greek efflorescence was exceptional in premodern world history. While ancient Greek economic growth fell far short of the growth rates experienced by the globe’s most highly developed countries since the nineteenth century, the ancient Greek efflorescence was distinctive for its duration, its intensity, and its long-term impact on world culture… While wealth and incomes remained unequal in those communities, a substantial part of the Greek population experienced relative prosperity. The growth of the Greek economy was driven, at least in part, by the ability of an extensive middle class to consume goods and services at a level well above mere existence.”

Ober presents a number of facts to that seem relevant to whether Ancient Greek city/states were Commercial societies:

Per capita consumption was up to twice subsistence levels, or $1000 annual income). This is on par with estimates for the city/states of Medieval Northern Italy and Flanders, though about half the average income for the height of the Dutch Republic and pre-industrial England.

This material standard of living was significantly higher than in the Persian, Egyptian, Roman, and other Ancient empires. Most likely, virtually all citizens in those societies lived at close to subsistence levels (roughly $500 annual income).

The authors estimate “Greek per capita growth during 800–300 BCE was probably about 0.15%”

Based on the size of houses, income was quite equally distributed. The late-classical Athenian level of wealth inequality is roughly comparable to that of the United States in 1953–1954 (Gini coefficient of 0.71).

Land was distributed even more equally. The Gini coefficient was 0.382–0.386, which is far lower than most Agrarian societies.

The authors conclude: “On the basis of the available evidence, classical Athens appears to be one of the very few known societies in the period 1800 BCE–1300 CE in which daily wages were substantially above the subsistence-level “customary wage range.”

The authors estimate that 32% of Greeks lived in cities, slightly higher than Britain in 1800 (though lower than the 45% for Holland in 1651).

At its height Ancient Greece consisted of 1100 states (!) with a total population of 8.25 million. About 200 of these had populations of over 10,000 (the minimum necessary for urban historians to consider it a city).

Three of those cities had a population of at least 100,000 residents (Athens, Sparta, and Syracuse).

Population densities were about 44 persons per square kilometer, similar to Holland in 1561 (45.3 persons) and England/Wales in 1688 (44 persons).

Each polis was either on or near a port. They were often not directly located in the Mediterranean for defensive purposes. Pretty much every location with a Mediterranean climate (for growing wheat, barley, and olives) and near the sea was occupied by a Greek colony.

Each polis was politically autonomous, although some were sister colonies that looked to their mother polis for leadership.

In each polis the adult males were citizens, not subjects.

Political power was highly dispersed among institutions with wide-spread and rotating offices held by regular citizens.

While many polis started as oligarchies, they gradually became more democratic.

About half of the population of each polis lived within the city walls. The city itself was surrounded by small towns, villages, and farmsteads.

Each Greek colony had its own city walls, public square, and marketplace, just as later Commercial cities did.

Every male citizen was a member of the militia, as was also typical in later Commercial cities.

Each Greek colony tended to have:

Specialization in exports (i.e. each polis exported different goods). This was typically based on natural resources that were unique to the locality

Internal specialization by trade and skills

Exports were both to other Greek cities as well as Egypt Persia, Thrace, and Scythia.

Non-Greek societies primarily paid for their goods with food and slaves.

Each polis had widespread horizontal specialization with many workshops and artisans, but very little vertical specialization using factories.

Each polis competed strongly with all the other polis in both economics and military. Wars were just as common as trade.

Transaction costs were kept low with innovations such as:

Silver coinage (mainly from Athens)

Standard weights and measures

Market regulations

Legal mechanisms for resolving disputes

Transaction costs were also kept low by a common language and a common culture.

The Verdict

Until we have more definitive economic data, particularly regarding how Ancient Greeks acquired their food, we cannot be definitive about whether they were Commercial societies. Having said that, Ober’s data gives clear indications that at the very least, the largest Greek city/states, were Commercial societies. It seems likely that a sizable percentage of the other 1100 city/states were also as well.

So, yes, I would say that Commercial societies existed in the Ancient Greek world. However, it is not clear how widespread Commercial societies were within the 1100 city/states. It might be that they all qualify, or more likely that only some of them did. Further research is needed.

My biggest hesitancy is the very sizable percentage of humans living in Greek society who were slaves. It is possible that Ancient Commercial required widespread slavery to be able to urbanize while using Ancient Farming techniques. This does not necessarily disqualify them from being Commercial societies, but it makes them very different from later Commercial societies that lacked slavery (except in overseas empires). It also makes Ancient Commercial societies different from modern capitalism in two ways (fossil fuels and slavery).

It is also quite possible that food imports were far more important than slavery in overcoming the limitations of Ancient Farming techniques, and slavery was just a “bonus.”

Given the above, it seems prudent to divide Commercial societies into two broad categories:

Ancient Commercial societies (with domestic slavery)

Medieval and Late Modern Commercial societies (without domestic slavery)

Were there other Ancient Commercial societies?

It is also possible that the Phoenicians and Carthaginians were also Commercial societies. Both had a strong resemblance to the Greek city/states and lived in very similar natural environments (in natural ports within the Mediterranean biome). But given the paucity of economic and food consumption data, I am hesitant to declare them as such. Other possible Commercial societies are the original city/states of the Middle East, Central Asian cities on the Silk Road, and the Mayans.

Did the Ancient Greeks experience material progress?

This is a separate, but related question. Commercial societies have a natural dynamism, but we should not assume that this leads to the “the sustained improvement in the material standard-of-living of a large group of people over a long period of time.“

If Ober’s data is anywhere near accurate, the answer must be “Yes” for at least a sizable percentage of the Ancient Greek world.

“ it seems prudent to divide Commercial societies into two broad categories”

This seems very reasonable.

One notable point is that during the Peloponnesian war, Pericles' plan was to pull all the Athenians inside the city walls and reply on imports for food. Unfortunately the overcrowding lead to plague, but economically the plan worked.