Before I present my proposal for overhauling the American welfare state, we need to understand the contours of the present system. Though we all live within and are affected by the American welfare state, very few of us have more than a vague understanding of how it works.

Rather than going into all the exhausting details of how each program works, let’s start by sorting them into categories of programs that work similarly. When viewed from a high-level perspective, there are three types of social programs in the United States: social insurance programs, means-tested programs, and tax expenditures. Each has different methods of solving social problems. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Social Insurance Programs

The first type of social program is “social insurance.” These programs give benefits to persons based upon a specific characteristic without regard to their income. Some examples of American social insurance programs are:

Social Security

Medicare

Unemployment Insurance, and

Disability Insurance.

The idea behind social insurance programs is that we are all potentially affected by bad events that undermine our ability to earn a decent income in the workforce:

old age

unemployment

sickness, and

disability.

Therefore, we should each pay a little bit of our income into a system, so we can receive help when the worst occurs. There is no separation between payers and beneficiaries. We all chip in, but we also all receive benefits.

Social Security gives benefits to a very high proportion of senior citizens. In general, if you are over 65 and you worked at least a few years in the private sector, you are eligible for Social Security. Unlike programs that are focused on fighting poverty, you do not have to be poor or near-poor to be eligible for Social Security benefits.

Social insurance programs are the most common type of social program in the Western world. Most European nations base their welfare states upon social insurance. Social insurance programs tend to be very popular because they benefit large swathes of the population.

Social insurance programs create the impression that everyone is paying into the system via taxes, but those same people are also receiving benefits at different times in their lives. So everyone feels like they are getting something.

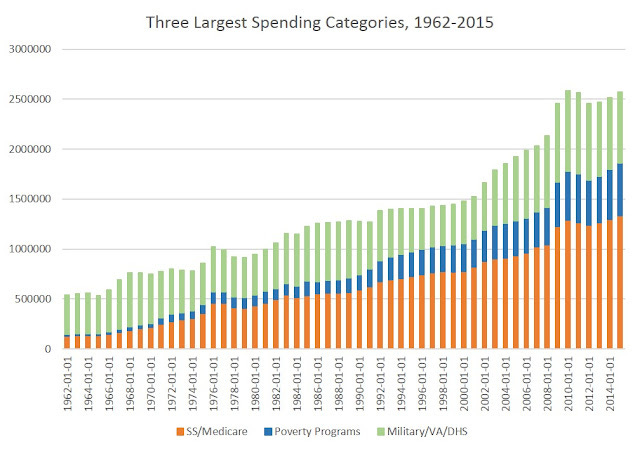

Social insurance programs, however, have two big problems. The first is that they are very expensive. Look at the budget of virtually any industrialized nation and you will see very sizeable portions of government spending devoted to social insurance programs. Because they are so expensive, social insurance programs require a very broad tax base. It is impossible to fund social insurance programs simply by taxing only the rich. One must also raise significant amounts of revenue from the middle and working class.

This leads to the second problem with social insurance programs. In general, social insurance programs are paid for via payroll taxes and value-added taxes (which function something like a sales tax), both of which hit middle- and lower-income people harder than the rich. In other words, social insurance takes money away from the same people that they give benefits to later.

This makes social insurance programs somewhat like a giant money-recycling system. Everyone pays higher taxes, and they get higher benefits in return. This leads to the logical question: Why not just let citizens keep their money and spend the money as they choose?

The primary counter-argument from their supporters is that social insurance programs place a floor below which no one in society can fall. Everyone pays more in taxes to ensure that no one is impoverished by old age, unemployment, sickness, or disability. It is for this reason that social insurance programs have been the bedrock of welfare states in Western nations.

Means-Tested Programs

The second type of social program are “means-tested programs.” Means-tested programs are “need-based” programs that deliberately focus their benefits on the poor and near-poor. While there is enormous variation among means-tested programs, they all include having low income as an eligibility criterion. Most Americans think of these programs as “welfare.”

Some examples of American means-tested programs are:

Medicaid

Food Stamps

Public housing.

While there is a huge diversity of means-tested programs, they all use income as a critical test for need. If a person has an income that exceeds a certain level, they do not qualify for benefits. Many programs have a gradual phase-out of benefits, so as not to produce a “cliff” of falling benefits once someone loses eligibility due to higher wages.

In general, the income level below which is needed to qualify for benefits is low enough that the vast majority of citizens do not qualify. The logic is that at a certain level of income, a person does not need help from the government, so it is better to focus funding on those who do need help (because they have a low income).

Means-tested programs have two big benefits. Compared to social insurance programs, they are relatively inexpensive. This is mainly because means-test programs completely exclude the rich, middle class, and working class from benefits. Except for Medicaid, means-tested programs are far cheaper than Social Security and Medicare.

The other advantage of means-tested programs is that they focus their benefits on those people who are most in need of help. While social insurance programs distribute huge amounts of money to people of average and above-average incomes, means-tested programs deliberately target the poor and near-poor.

A critical problem with means-tested programs, however, is that they tend to be politically unpopular. Means-tested programs inherently create two different groups in society:

those who receive benefits and

those who pay the taxes for those benefits.

Particularly if those two groups tend to be from different racial or ethnic groups, this inherently creates resentment. The strongest resentments tend to come from people who work hard at lower-wage jobs and they see beneficiaries who do not work but have a standard of living similar to their own.

An even bigger problem is that means-tested programs reward failure and penalize success. If a person takes all the right actions to build a successful life, they will likely have an income too high to qualify for benefits. If a person devotes little effort to improving their circumstances, they will likely qualify for higher benefits. Since most of the people who pay for the programs realize this, this incentive structure undermines political support to an even greater degree.

While Americans take means-tested programs for granted as a normal part of a welfare state, they are very rare in the rest of the world. Except for Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, welfare states in the rest of the world are dominated by social insurance programs. The American focus on means-tested programs sets itself apart from most welfare states in the rest of the world.

Tax Expenditures

The third type of social program is tax expenditures, more commonly known as “tax loopholes.” Tax expenditures are essentially the government deciding that certain types of consumer or corporate spending should not be taxed. These exclusions are generally made because that type of spending is considered socially desirable. Some of the most common tax expenditures are:

home mortgage deduction,

charitable donation deduction, and

business expense deductions.

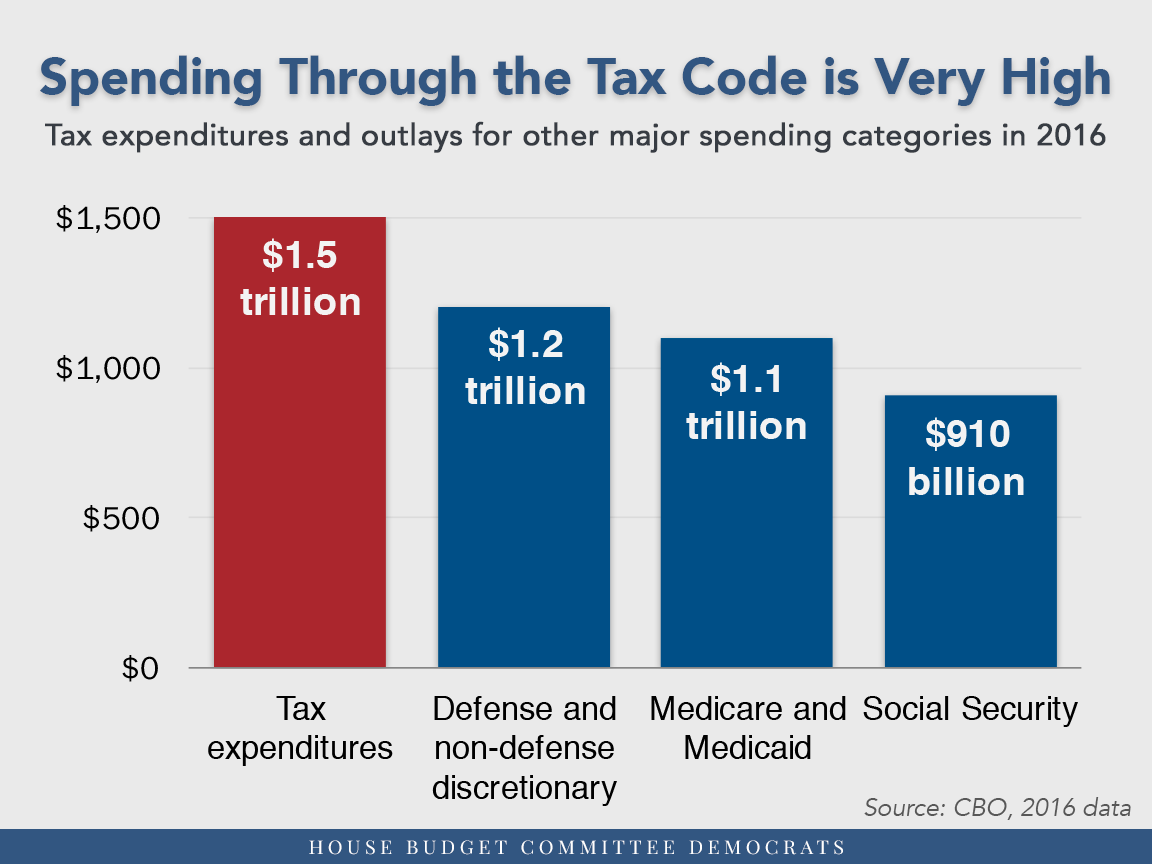

Tax expenditures have the benefit of appearing to be free. By that, I mean that this type of expenditure does not show up on the government’s budget, so these programs completely sidestep the entire budget process. Most people do not think of tax expenditures as a social program at all.

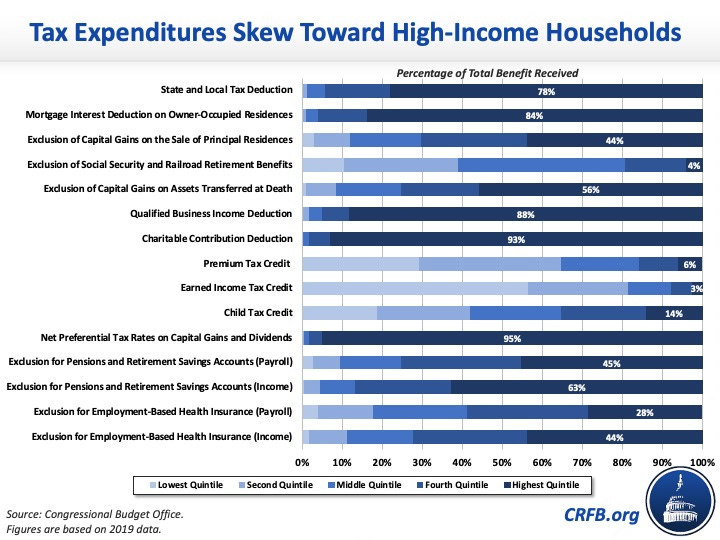

Tax expenditures have one huge drawback in that they primarily benefit upper-income persons. Because income taxes are progressive (i.e. high-income persons pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than low-income persons), any income that is deducted is worth more to a high-income person than to a low-income person.

In some ways, tax deductions function as a reverse means test. Persons with low income generally do not benefit from tax expenditures for the simple reason that their income is too low to pay much in taxes. Only persons with fairly significant tax bills, i.e. upper-income persons, get significant amounts of money from tax expenditures. This “feature” of tax expenditures was not the original intention, but it is the result.

The other drawback of tax expenditures is that they make our tax system extraordinarily complicated. With thousands of tax expenditures that are changing each year, federal taxes have become so complicated that even qualified accountants do not understand all the intricacies. Tax expenditures exist in all nations, but the United States has far more than any other.

So when we look at the American welfare state in its entirety compared to other nations, the United States looks very unusual. Most developing countries have little to no welfare state. The welfare state of virtually all other wealthy Western nations is dominated by a few large social insurance programs, such as pensions, and health care. Means-tested programs and tax expenditures are far less common. The United States, in comparison, spends far more money on means-tested programs and tax expenditures.

It is far from clear that this strategy is getting positive results.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Great piece. I did not know that means-tested welfare is rare outside of the US. Is this true? I could spend all day discussing this topic, for I agree that the welfare system is fundamentally broken. I see evidence all around me that means-tested programs are not working; they trap people under an arbitrary line that officials have labeled as “poverty.” And yes, they do breed resentment because they do not properly discern who “needs” help from those who don’t.

If I send my child to daycare, it will cost me $1000s per month, yet there are parents going to the same facility that need to pay less than $25.00 for the same thing…why?

What gives the government the right to reach into my pocket and hand my money (essentially my time on Earth) and give it to someone else who has not been willing to make the same sacrifices that my wife and I make?

A minor quibble though, a VAT tax, as I discussed here, is not as regressive as it appears: https://www.lianeon.org/p/in-defense-of-the-vat

To be clear, I think some safety net is a good thing, so long as it doesn’t create a tangled ball of debt that we cannot escape from, and incentivizes people to work hard and better themselves. I don’t see any reason the government cannot, for example, set aside one’s income for them in a retirement account or HSA for their personal benefit as I suggested here: https://www.lianeon.org/p/rethinking-social-security

My model of welfare spending is thus:

1) Politicians want to win 51% of votes.

2) They have limited resources to spend.

3) They try to buy votes as cheaply as possible to reach 51%.

4) People with low incomes are potentially cheaper votes, because a marginal dollar of welfare is worth more to them.

5) Hence the retired, single women, and the underclass.

6) You can "double dip" on this spending if it takes the form of professional services, because it can be a way of buying off both the receiver of the benefit and the provider (doctors, nurses, social workers, teachers, etc).

7) There is a strong demand for "social insurance", that is insurance that the private market can't perform cost effective underwriting for. But it's easy to mix this in with cross subsidy and welfare. This is very common in health insurance.

8) Social insurance is also easier to implement in societies that are largely equal to start with (Nordics, Asians) and hard to implement if you have a significant underclass (USA).

9) People with more income are easier to sell ideology too. Having fulfilled their basic needs, they want to be told a story, and they are willing to pay taxes to hear it. If you can sell them ideology you can divide the votes of the taxed class.

10) Add to all that common issues of groupish voting, propensity to vote, status quo bias, coalition politics, etc.