The period between 1947 and 1965 marked a time of tremendous Upward Mobility for the American working class and poor. While many researchers compare the increases in the standard of living for the American people today unfavorably to this period, few analyze the past to find out why. They usually skip right to policy prescriptions to improve the current situation. But if one does not understand why the period between 1945 and 1965 had so much upward mobility, then one cannot create policies with a high chance of success.

Read more of my articles on American Progress and Upward Mobility:

You might be interested in reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Limited government social programs

One key difference between today and the period between 1947 and 1965 was that the American welfare state was far more limited than it is today. Let that sink in for a moment. During the period when the working class and the poor were experiencing far higher rates of upward mobility, government programs designed to help those people were far less in extent.

Before 1965:

There were essentially no government health care programs, except for veterans. Medicare and Medicaid did not exist until 1965,

Social Security benefits were much lower than today

Disability Insurance was just getting started, and eligibility requirements were much tighter than today.

More importantly for our discussion, means-tested programs (i.e. programs for the poor and near-poor) were almost non-existent. The vast majority of those programs were enacted during the Great Society in the mid-1960s. Aid for Dependent Children existed, but the beneficiaries were composed almost entirely of widows with children.

In 1951 only 3.8% of people received some sort of public aid. By 2012 the proportion had grown to more than eight times that level: 32.3%. This was despite people having a drastically lower standard of living in the previous era.

The result was a dramatic difference in incentives for poor and working-class families compared to today. Everyone knew that the only way they could survive was to get a job or get help from their families. There was simply no other option.

Strong Economic Growth

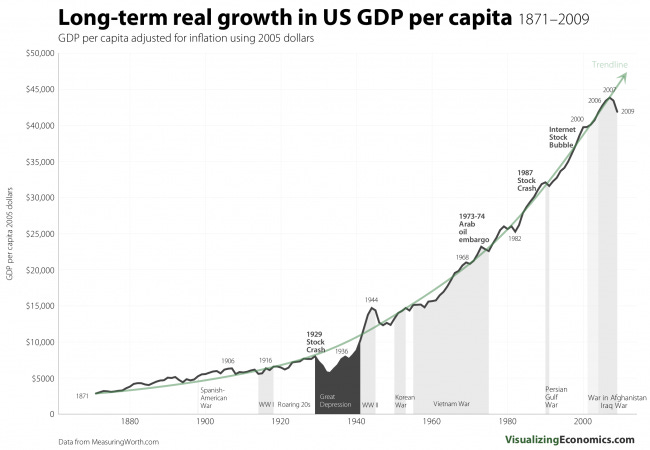

The single biggest reason for the upward mobility of the American working class between 1947 and 1965 was strong economic growth. In some ways, this economic growth was caused by unusual historical conditions that are unlikely to be repeated. If one looks at economic growth over the past few centuries, a very clear trend line emerges, but the period between 1929 and 1946 departs from this trend.

The Great Depression was the greatest economic crisis in American history, and it dragged on for more than a decade. Then during World War II, American economic effort was channeled into the military.

From the start of the Great Depression in 1929 until just after the end of World War II, consumer demand was very weak. Throughout the Great Depression, most workers were more concerned with getting food and shelter rather than buying consumer goods.

Even after the Great Depression came to an end strong war-time rationing held back demand throughout most of the 1940s. For a full 17 years between 1929 and 1946, American consumer spending had been kept far lower than in previous eras.

Starting with the pre-war recovery in 1947 and then carrying through until the oil embargoes of 1973, American consumer spending surged. Americans bought huge amounts of every consumer item that was available at the time. Due to the enormous innovative capacities of the American industry, more consumer goods were coming online each year. The result was a full generation of strong economic growth.

For many economic historians, this period was a golden era of American economic growth. The period certainly saw stunning economic growth, and the benefits of that economic growth were disproportionately gained by the working class. It is easy to see why egalitarians can view this period in a very positive way.

I have some doubts, however, whether the conditions of this period can be repeated. At its core, the economic growth from the period was due to two unusual factors. The first was the post-war economic recovery from the devastation of the Great Depression and World War II. Europe and Japan lay in ashes in 1945. The United States stood triumphant economically, but its entire industrial base had to shift from military production to consumer production.

Second was the implementation and diffusion of key energy and transportation technologies invented in the period between 1867 and 1914: fossil fuels, the electrical grid, electric motors, the internal combustion engine, automobiles, trucks, tractors, marine diesel-powered ships, and airplanes.

All of these very complex technologies took generations to work out and integrate with the rest of the economy. The Great Depression and World War II interrupted this process, so once the economy returned to normal economic growth, the Americans had a huge reservoir of technologies to diffuse through the economy. Once the skills and designs related to these technologies were mastered and consumers had the money to purchase those technologies, economic growth soared.

This does not mean, of course, that we cannot improve our current level of economic growth. Far from it. It does mean, however, we have to be careful of looking back to the economic growth of the period between 1947 and 1973 as normal. Most likely, economic historians of the 22nd century will look back on that period as decidedly unusual.

Little Foreign Competition

Another key factor in the period between 1947 and 1965 was that the American economy faced very little foreign competition. During World War II the economies of Western Europe and Japan were devastated. While their economies did recover sharply starting in the late 1940s, Europeans exported relatively few goods to the United States. And imports from East Asia were even less.

While Japan was slowly ramping up the level of its imports to the United States during this period, it had relatively little impact on American society. The idea that American workers should be concerned about foreign competition was just not something that occurred to anyone during this period.

The combination of strong consumer demand, a huge backlog of technological innovation, and limited overseas competition was a boon to American industry. As long as a product was somewhat of an improvement over what had existed previously, it would fly off the shelf.

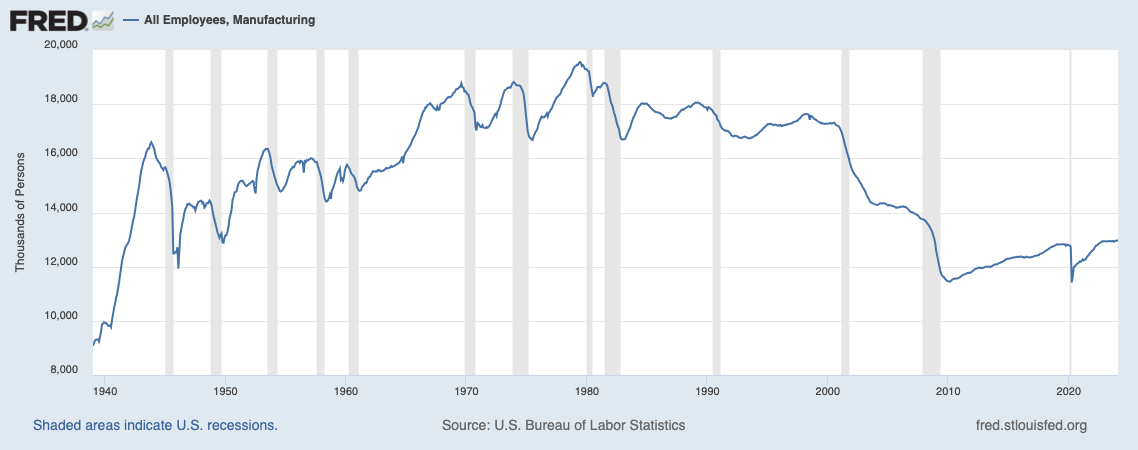

Large Manufacturing Sector with Limited Domestic Competition

The American economy from 1947 to 1965 was dominated by the manufacturing sector. And this manufacturing sector provided huge numbers of jobs. In many regions, a young male could drop out of high school and be assured of getting a steady job in a factory until his retirement.

While factory jobs paid very poorly compared to today’s salaries were tedious and dangerous, they seemed like good opportunities at the time. More importantly, those wages increased almost every year giving everyone confidence that the positive trend would continue in the long term.

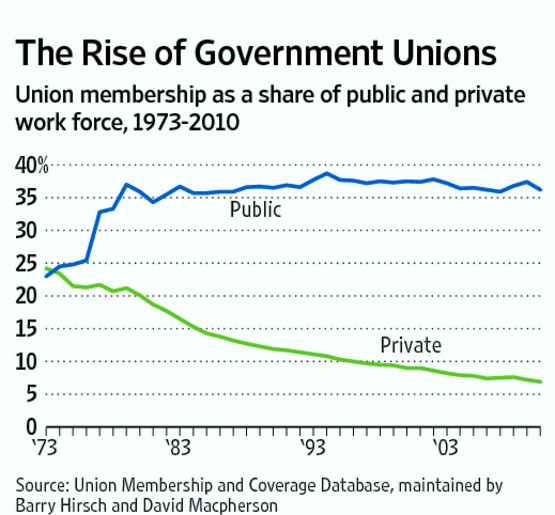

Trade Unions

A key reason why the working class benefited from the economic growth from 1947 to 1973 was widespread private-sector trade unions. While today private-sector trade unions are a relatively minor portion of the workforce, between 1947 and 1965 they played a very important role in the economy.

In the 1950s about one-third of the private sector workforce were union members. This compares with only 6% in 2020. The combination of little overseas competition, a manufacturing sector with limited competition, and strong trade unions put workers in a strong bargaining position. They could demand higher wages and benefits without worrying that it would lead to significant job loss (Brookings 2019).

In previous periods, employers fought hard against unionization and strikes. Some even used violence. But with the combination of New Deal Democrats, who were strongly pro-union, and robust economic growth gave American employers a strong incentive to buy labor peace. The pie was growing in size so fast that there was no point in getting into a life-or-death struggle with trade unions. By the 1950s most manufacturing companies were unionized to one extent or another.

It is important to note, however, that public-sector unions (i.e unions for government workers) were much weaker than today. While one-third of government workers are unionized today, back in the 1950s the level was in the single digits. The reason is simple: while New Deal Democrats were strongly supportive of private-sector unions, they were generally opposed to public-sector unions. This would change after the 1960s (Brookings 2019).

Because manufacturing companies generated very high profits from strong economic growth, limited domestic competition, and virtually no foreign competition, they agreed to union demands for constantly increasing pay, benefits, and job security. Particularly for the least educated American workers, this drastically increased their standard of living.

A high school dropout born in 1930 who lived in an area with many factories could realistically expect to work in a secure job with constantly increasing income and benefits. Most likely he expected his sons to be able to do the same.

Very Low Rates of Immigration

The period between 1947 and 1965 in the United States had unusually low rates of immigration. While the period between 1820 and 1914 saw historically high rates of immigration, this was not true of the post-war period.

Starting in 1820 and then increasing throughout the 19th Century, immigration rates to the United States were very high compared to any previous society. This created a constant stream of cheap labor to work in American factories and farms. High rates of immigration to the United States peaked around 1910. According to the U.S. Census, a full 14.7% of the population were immigrants in that year. And these immigrants were heavily concentrated in industrial cities with lots of low-skilled factory jobs.

During World War I immigration declined precipitously. Just as rates of immigration began to recover after the war, the Immigration Act of 1924 drastically curtailed levels. This act banned immigration from Asia, except the Philippines, and capped immigration to two percent of the total population of each nationality in the 1890 census.

Since most of these nationalities were European nations with relatively few potential emigrants, overall levels of immigration declined precipitously. This state of low rates of immigration remained until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The result of this decline in annual immigration was a precipitous decline in the percentage of Americans who were immigrants. According to the U.S. Census, the percentage of Americans who were immigrants dropped to 4.7% in 1970, less than one-third of the levels of 1910. This was the lowest level on record.

Without a massive influx of cheap immigrant labor to cut working wages, American employers had no choice but to constantly increase wages for low-skilled workers. Low rates of immigration placed labor unions in a strong negotiating position. The strong profits from economic growth and limited competition gave employers the surplus revenue to channel towards increased wages, benefits, and job security.

Higher Rates of Geographical Mobility

Another key factor promoting upward mobility between 1947 and 1965 was very high rates of geographical mobility. As I explained in my book, From Poverty to Progress, progress is always highly localized. Due to geography, technological innovation, and other factors, the regions that experience economic growth are constantly changing. This means that the ability and the desire of people to relocate to booming economic regions is key to upward mobility.

Between 1947 and 1965 working class and poor families frequently relocated to different neighborhoods and metro regions in the search for affordable housing and job opportunities. The combination of very low levels of means-tested government spending, affordable housing, affordable transportation, and a booming economy gave people a strong incentive to relocate.

Today relocation is more typical for professional-class families than working or poor families. Between 1947 and 1965 rates of relocation were higher for working or poor families.

Particularly for Blacks

Low levels of immigration of cheap labor particularly benefited African Americans. As agriculture in the Deep South mechanized in the early and middle 20th Century, there was less need for cheap labor in the region. Modern transportation and communications made it easy for African-American sharecroppers to jump on a train and move to the booming industrial cities of the Midwest and Northeast.

The period from World War I until the 1960s saw one of the most dramatic internal migrations in American history. Indeed, it is probably one of the greatest migrations in world history. From 1917 until 1965 African-Americans effectively played the same role as previous generations of immigrants from Europe: a cheap source of labor for factories. The result was just the same as for immigrants: upward mobility for African Americans.

Affordable Housing

A key factor in that increasing income translating into a higher standard of living was the abundance of affordable housing. Between 1947 and 1965 there was a tremendous boom in the construction of single-family residences. The vast majority of that construction took place on the outskirts of major metropolitan areas. The modern suburb was born during this period.

Today residents of the major metropolitan regions of the Northeast and Pacific Coast take rampant housing cost inflation for granted. In these areas plus a few others, housing inflation has been going on for so long that it is difficult for people to imagine anything else.

Hard as it is to believe today, changes in housing prices closely matched income between 1947 and 1965. Perhaps even harder to believe is the fact that hardly anyone noticed. Housing prices stayed pegged to 1.8 times the median family income, and there was very little variation between metro areas. Richer areas had more expensive houses, and poorer areas had less expensive houses, but the ratio between median housing costs and median family income varied little.

The cause of this stability was nothing mysterious: homebuilders constructed single-family residences roughly as fast as families wanted to buy them. And they built most of those houses on the outskirts of metro areas where land was cheap. The fact that home builders could keep up with demand in the middle of the Baby Boom is a testament to the power of market forces.

With constantly increasing incomes and affordable homes, Americans had plenty of money left over for consumer purchases. And each year, except for a few mild recessions, their incomes grew. This further fueled the post-war expansion.

Integration of Ethnicities in Suburbs

World War II and the following post-war economic boom witnessed a profound change in the geographical dispersal of American ethnic groups. Before World War II most ethnic groups were highly concentrated geographically.

Today many people think of Americans as being divided up into four large racial groups: Whites, Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics. Before World War II, however, most people outside of the South thought in terms of ethnicities and religions, rather than race. There were no White Americans; there were Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, German Americans, Norwegian Americans, Polish Americans, and Irish Americans. Outside of the Deep South, people did not even think in terms of race. Each of these ethnic groups was heavily concentrated geographically.

Northern New England had a British majority with a strong French-Canadian minority, particularly near the Canadian border. Southern New England had a British majority with a strong Irish Catholic minority in the cities. And each neighborhood was clearly either British or Irish. Few lived in the “wrong” neighborhood.

The New York City region was even more divided. While one might look at the overall composition of the city and declare it “diverse,” any individual neighborhood was nothing of the sort. A neighborhood was either British, Italian, Irish, Black, Jewish, or one of the dozens of other ethnic groups that lived in the region. At the national level, America was extremely diverse. At the regional and neighborhood level, America tended to be ethnically homogeneous.

The rural regions stretching westward from Pennsylvania through the Middle West were heavily German. The northern tier of the rural Midwest was heavily Norwegian, Finnish, Swedish, or Danish. The industrial cities of the Midwest were similar to New York City with a wide variety of ethnically homogenous ethnic groups, primarily from Eastern Europe. The only region that was stratified by race was the Deep South with its classic White/Black divide.

Just as important, many of these ethnic groups were divided internally by religion. This was particularly true of the two largest minorities: the British and Germans. Americans of British descent often identified themselves as Methodist, Baptist, Mormon, or Episcopalian. Germans were divided into Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. Each group kept to themselves socially and rarely socialized outside their religious group.

What this effectively meant was that ethno-religious groups were highly segregated until World War II. If those levels of ethno-religious segregation had continued during the post-war economic boom, it would have produced great inequalities between groups.

Ethno-religious groups living near factories would have prospered, while those living far from the factories would have missed out on much of the progress. The massive amounts of construction of single-family residences on the outskirts of growing metro areas ensured that this did not happen.

After World War II, young families from previously ethnically-segregated neighborhoods in the cities moved to brand-new houses in the suburbs. All the people from those segregated urban neighborhoods suddenly lived together in the same suburban neighborhood. Not surprisingly, many of them fell in love with each other, got married, and had children. After a few generations of this process, ethno-religious diversity and segregation among whites melted away. Just as important, those young families enjoyed the benefits of strong economic growth.

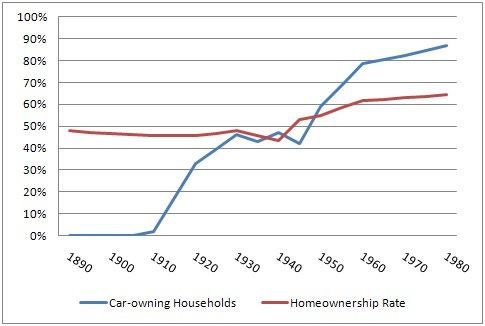

Affordable Transportation

Those new ethnically mixed suburbs could not have flourished without access to jobs. Since factories and offices were located far from the suburbs, this meant that families needed affordable transportation to get to those jobs. Highways and cars provided a solution.

The Federal Highway Act of 1956 paid for an enormous amount of highway construction that lasted well into the 1970s. The highways authorized by this bill made transportation faster, safer, more fuel-efficient, and less time-consuming than traditional roads. Most importantly, it radically expanded the employment and shopping options for urban dwellers.

The original intention of the bill was to connect metro areas for national defense, but their more profound results were to knit together neighborhoods within each metro area into one economy. Workers could now live anywhere within the metro area and still have access to jobs in factories or businesses in distant neighborhoods.

Just as important as highway construction was a dramatic increase in both the purchasing and driving of cars. Without cars, people could not take advantage of the new highways being built. Car ownership increased from under 45% in 1945 to over 80% in 1970. The automobile went from a luxury affordable only available to the affluent to a necessity affordable to all but the poor.

The rapid expansion of both cars and highways gave American workers a level of daily mobility that was unparalleled in human history. Whereas previously people rarely moved more than 10 miles from home during their lifetime, now millions of Americans are doing it every day.

Affordable Energy

Buttressing this entire transportation network was vast amounts of domestic energy production. During this period the United States was energy independent. Coal, oil, hydropower, and later natural gas and nuclear power were all domestically produced. More importantly, all of the energy derived from these sources were affordable.

Between 1947 and 1972 energy prices increased slower than the overall rate of inflation. Given that lower-income people pay a significantly higher percentage of their total spending for energy, this greatly helped their standard of living. Commuting to work from suburban homes, heating/cooling homes, and running electric appliances was accessible to the vast majority of Americans.

Then between 1973 and 1981 two separate OPEC oil embargoes caused oil prices to increase far higher than the overall rate of inflation. Since then energy prices have been volatile with periods of price declines followed by periods of rapid price increases.

Affordable Health Care

Health care was far more affordable between 1947 and 1965 than today. This might surprise some as Medicare and Medicaid did not exist, and employer-covered health insurance was far less generous in coverage. While we do not have comprehensive data on the topic, in 1960 about half of all medical spending was paid for in cash. One might think that this made health care unaffordable to all but the rich, but the result was the opposite.

Now it is important to point out that the medical care that we have today is far superior to what existed between 1947 and 1965. The medical miracles that we take for granted today simply did not exist during that time. Not surprisingly, rates of neonatal mortality and adult longevity were much worse than today.

The key point for our purposes is that the medical care of that period was much cheaper. Few people ran into financial problems trying to pay for medical care. Most had no trouble paying in cash. That is a far cry from the situation today.

Much Higher Rates of Male Labor Force Participation

The predictable result of all the above was a far higher labor participation rate than today. In 1964 only 6% of all non-institutionalized men were not working or looking for work. In 2012, that number had almost tripled to 17%.

It is important to point out that married women with children had significantly lower rates of labor force participation than today. Single women and married women without children had relatively high rates of labor force participation, but as soon as they had children they dropped out of the labor force. What made this possible without increasing poverty were very high rates of marriage.

Very High Rates of Marriage

A key cause of the upward mobility between 1947 and 1965 was the very high rates of marriage. Families with children during this period were almost invariably married couples who were the biological parents of their children. The exceptions were usually widows whose husbands died young and members of the extended family who took care of children when their parents could not.

Divorce rates were low (except for a brief spike immediately after World War II), and single mothers having children without getting married were even rarer. It is important to understand that these factors were not unique to this period. It was an extension of how things had been for centuries.

The result of very high rates of marriage was a strong foundation for children. In particular, fathers could teach sons skills, habits, and values that would enable them to be successful adults. Compared to today, a child living without their biological father was rare. And for those children who did, the cause was usually early death by the biological father. So while the father died, the idea of the father did not.

As would be expected, this resulted in lower rates of crime and a faster transition of young men from school to employment to family.

Read more of my articles on American Progress and Upward Mobility:

Books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Thanks Michael.

Around the mid 60s everyone just kind of decided they should have things they want without paying for it, and that somehow it would work out.

Free love and easy divorce without it affecting family formation.

Drug use without social dysfunction.

Gov spending without taxes, or at least with other peoples taxes.

A war in Vietnam where rich kids get deferments.

Fed money rather then balanced budgets.

Loose on crime laws without getting more crime.

Solving racial divisions not by changing hearts but government dictate.

Labor unions wanting better and better terms even as the products they were making were getting worse and worse.

Just an incredible explosion of lack of responsibility.