Was the fall of the Roman empire necessary for modern progress?

Or was it the failures of all other European empires?

In my book series and Substack column, I focus on the concept of the Five Keys to Progress. I believe that the Five Keys to Progress is an essential unifying concept for understanding human material progress. They are critical because they are the necessary preconditions for a society changing from a state of poverty to a state of progress, and they are actionable in today’s world. In other words, the concept not only helps to understand the world but also how to make it better.

The third key is Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. It is of particular importance that elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses. This also allows citizens to freely choose among institutions based on how much they have to offer to each individual and society in general.

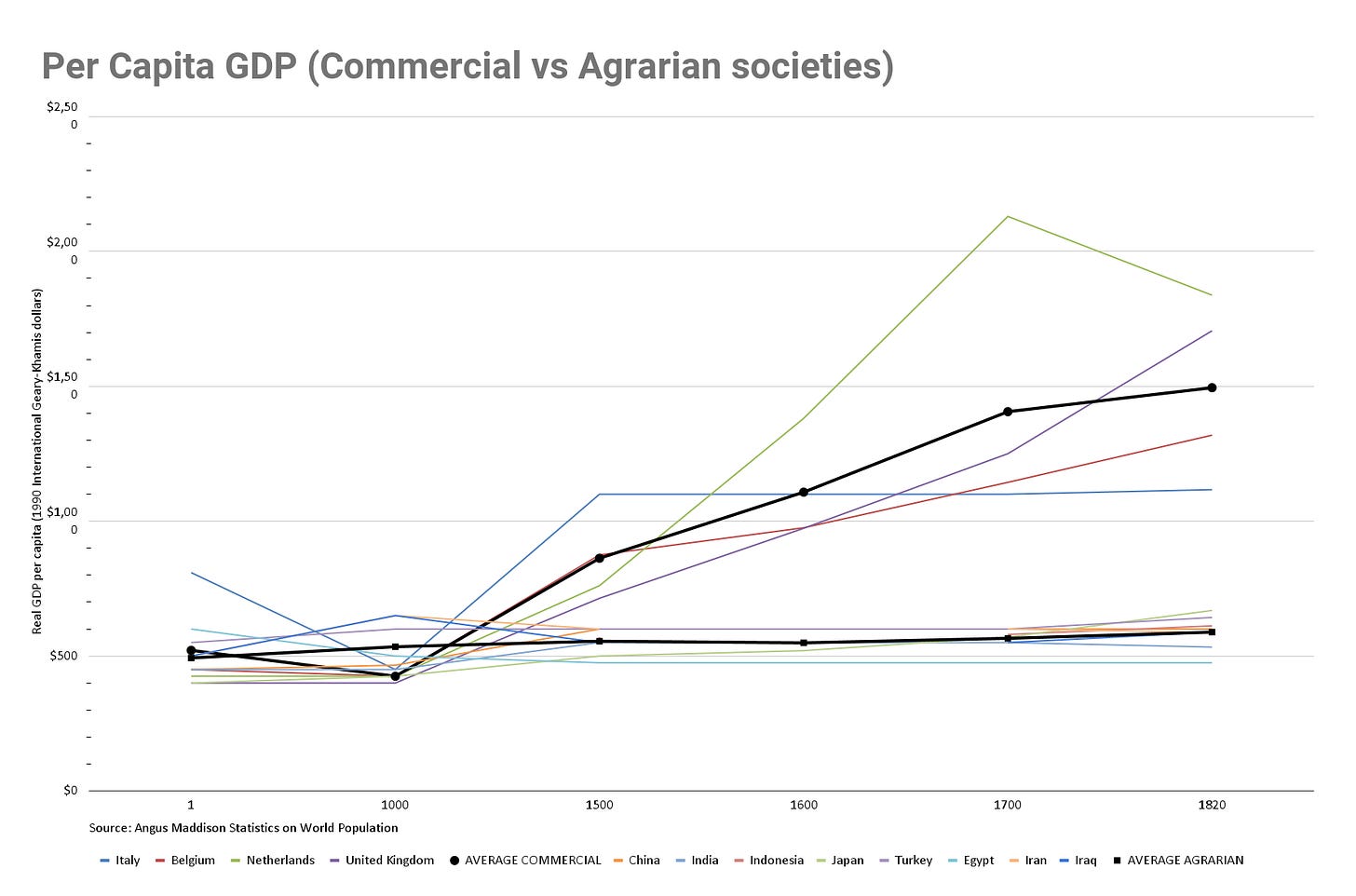

Unfortunately, Agrarian societies typically evolved into large empires that suck up all the resources from their region. The food surplus from agriculture (the first Key) that could have been used to feed trade-based cities (the second Key) was instead redirected to enhance the wealth, power, and prestige of the landed elites who dominated Agrarian empires. The Roman Empire and the Chinese Empire are just two of the most well-known examples.

If one looks from a very high level at the history of Agrarian regimes on the Eurasian continent, one can see a cycle of:

Predatory empires grow through military conquest.

Predatory empire collapses due to defeat in war, civil war, or failure to produce a legitimate male heir.

The Old Predatory empire is replaced by a newer and more dynamic predatory empire that produces a more effective military.

the cycle continues….

Chinese history is where this is most obvious, though similar cycles appear throughout Eurasia. Except in one region: Europe.

Europe certainly had more than its fair share of predatory empires, including:

Macedonians

Romans

Byzantines

Carolingians

Spanish (in the 16th and 17th Century)

French

German (in late 19th and 20th Century)

Russian and Soviets

What was unusual was that none of them established a continent-spanning empire for more than a brief period. The only real exception was, of course, the Roman Empire. which dominated the European continent for more than five centuries. Its collapse, or more accurately the collapse of the Western half of the Roman empire, is widely considered to be one of the most important events in European history.

What was unusual, however, was not the collapse of the Roman empire. It was the fact that it was never replaced by a hegemonic empire. Despite many attempts, no one society every dominated the European continent.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

This article is one article in my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

The Holy Roman Empire was an incubator of Progress

Was the fall of the Roman Empire necessary to Progress? (this article)

The Legacy of the Fall of the Western Roman Empire

As Walter Scheidel argued in his book Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity (summary here), Europe differed greatly from the rest of Eurasia in its formation of empires. While most of Eurasian history was dominated by a succession of empires, once the Roman Empire collapsed, European history was not. While the Franks, Carolingians, Spanish, French and Germans all tried to create continent-spanning empires, they all failed. Instead, Europe was fragmented into many competing kingdoms. This was a very different outcome from the rest of Eurasia.

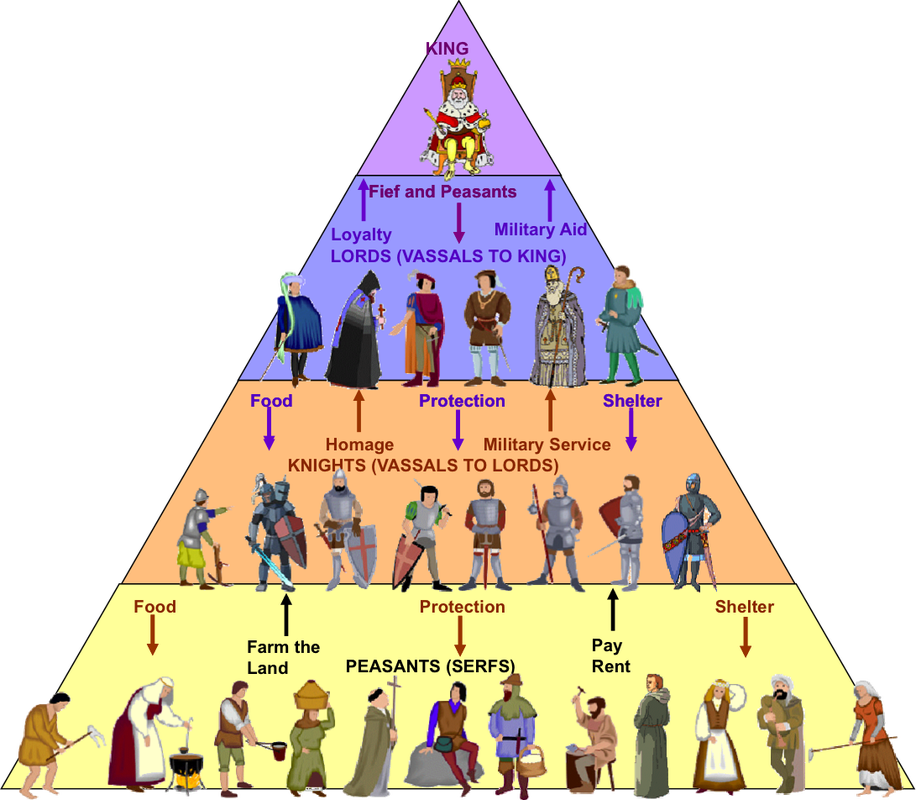

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Northwestern Europe experienced a radical decentralization of the political, economic, and religious power called feudalism. While the rest of Eurasia evolved strong centralized governments with powerful extractive political and economic institutions, Northwestern Europe was highly fragmented by feudalism.

From the fall of the Roman Empire until the consolidation of nation/states in the 16th century, Europe was fragmented into tiny domains run by individual nobles or bishops. To give you an idea of how small these polities were, take a look on the map at the size of the few that still remain: Monaco, San Marino, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg and Andorra. Of course, there were larger Duchies and Counties, but few of them approached the size of modern-day states.

This political and institutional fragmentation enabled the rise of Commercial societies in Northwest Europe. Most cities and towns inhabited but a portion of these small political units. Sometimes by fighting for independence, but more often by bargaining with their lords peacefully, trade-based Medieval cities gradually carved out a level of political autonomy that was unheard of anywhere else in the world. Some of these cities evolved into independent polities, but most won a de facto autonomy on economic and political issues conditional on paying a communal tax to their lord.

Many lords found that by granting their cities and towns exemptions from feudal dues, they could generate greater revenues. Other lords offered autonomy to encourage settlers to move into their more sparsely settled regions. Because cities and towns created so much more wealth than even the most productive countryside, savvy nobles could make more money with a light touch.

Let me be clear. Commercial societies did not emerge in feudal realms. Commercial societies required free labor, while feudalism required serfdom.

But because feudalism was inherently decentralized, there were often small regions where serfdom and feudal lords were absent or weak. If those regions had geographical factors that favored the growth of trade-based towns, those towns had a real chance to grow into societies that were completely different from the surrounding feudal societies. Commercial societies evolved where both feudalism and centralized Agrarian institutions were weak or absent.

And it was Commercial societies that created human material progress.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

This article is one article in my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

The Holy Roman Empire was an incubator of Progress

Was the fall of the Roman Empire necessary? (this article)

How humans learned to transform food surplus into Progress (upcoming)

Another way of looking at pre-Industrial England (upcoming)

Economic growth before the Industrial Revolution (upcoming)

How European settlers spread progress (upcoming)

The significance of the Industrial Revolution (upcoming)

Was the Industrial Revolution inevitable? (upcoming)

The Great Power conflicts of the 20th Century (upcoming)

Progress since 1991 (upcoming)

> The third key is Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. It is of particular importance that elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses.

Thinking about it, this requires extremely specialized circumstances. Political, economic, religious, and ideological power must be decentralized, while military power is just centralized enough to stop the elites from resorting to violence in their competition, but not centralized enough to centralize the other types of power.

I think there is some truth to this. As others have noted, the failure of any single nation to conquer and hold Europe made it harder to persecute intellectuals.

If the printing press was not welcome in one country, the inventor need only move a short distance to another and bring the invention with them.

European rulers eventually learned that if they persecuted those with new ideas, sometimes those ideas would end up in the hands of their enemy. Thus, a culture of tolerance gradually emerged.