Medieval European cities

How they gained independence from their local lords and helped to create modern progress

In my book series and Substack column, I focus on the concept of the Five Keys to Progress. I believe that the Five Keys to Progress is an essential unifying concept for understanding human material progress. They are critical because they are the necessary preconditions for a society changing from a state of poverty to a state of progress, and they are actionable in today’s world. In other words, the concept not only helps to understand the world but also how to make it better.

I have already written several articles explaining how Northwest Europe achieved the first Key: A highly efficient food production and distribution system. This enables societies to overcome geographical constraints to food production so that large numbers of people can focus on solving problems other than getting enough food to eat.

Essentially, Northwest Europe went through a series of major transformations in its farming system, each more productive than the other:

The Ancient farming system, which was the system used during the times of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and the Dark Ages

The Medieval farming system, which was unique to Northwest Europe. It was invented sometime between 700 and 900 and lasted until the 19th Century.

The Commercial farming system, which laid the foundation for Commercial societies.

But farming by itself does not create material progress; it is merely one precondition. Progress actually happens in the cities. Farmers create the food surplus, while cities create the progress. But to do so, cities need to have a certain amount of autonomy. A city that is dominated by land-owning elites is unlikely to be innovative. All of its citizens will cater to the whims of landed elites. Such was the fate of almost all cities in Agrarian societies.

Medieval European Cities

Northwest Europe, however, was lucky enough to see the development of relatively autonomous trade-based cities. Most historians view this as a key reason why Europe grew in wealth and power long before the Industrial Revolution. One note: historians typically use a population of 10,000 as a cut-off between a village and a city. By today’s standards, almost all Medieval cities were small towns. It is also important to not that Eastern Europe and Mediterranean Europe had very different types of cities, so here we are mainly talking about Northwest Europe plus Northern Italy.

Medieval cities had a few key characteristics that made them unique in world history:

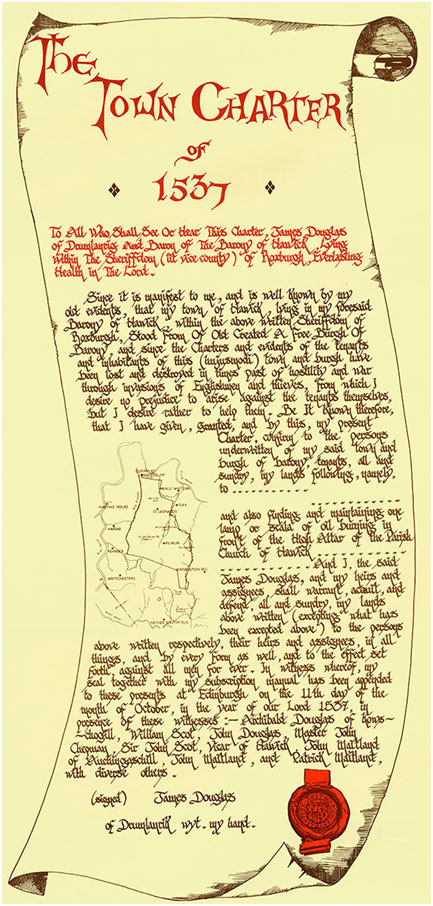

They had a town charter that was signed by the local lord and the city notables at the time of its formation. The town charter typically gave the city de facto internal autonomy on the condition that the city paid the lord an annual tax. That tax was typically collected by the city government in the manner of their choosing.

Its own criminal and civil judicial and tax system. In return for regular taxes, the local lord gave up his rights to be the de facto judicial and tax system. This gave medieval cities unheard-of autonomy compared to other cities in Agrarian societies.

No serfdom or other forced labor. While Medieval countryside was dominated by serfs who were tied to the land and were completely dependent on their lords for law, order and defense, Medieval cities had no serfdom. The importance of this cannot be understated. While most agricultural societies were dominated by one form of forced labor or another, Medieval cities were dominated by free labor. This made Medieval cities a microcosm of modern societies.

A militia where most able-bodied men served. Being an autonomous town did not release the town from military obligations to the king, emperor, or other lords. They still had the obligation to defend themselves and conduct offensive campaigns at the king’s pleasure. Town militia typically consisted of archers and heavy infantry and lacked knights and armed serfs. This made them very different from typical medieval armies.

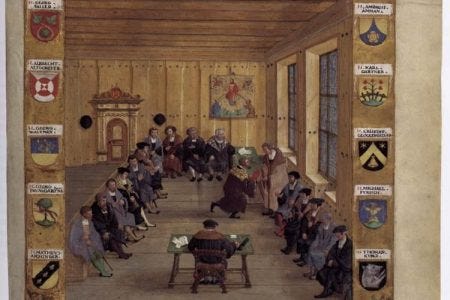

A town hall. The beating heart of the Medieval city was the town hall. It symbolized its autonomy from the feudal countryside. It is where the town notables gathered to make all important decisions as well as daily governance.

A town council, usually consisting of merchants elected by their peers. Typically, the town also had a mayor, although sometimes the town council functioned as a collective executive. The town council administered the judicial, fiscal, and military affairs.

City walls to separate the jurisdiction of the city government from the local countryside which was run by the local lord. Typically, artisans, merchants, and the laboring poor lived within the city walls, while serfs lived outside the walls.

The city walls became essential during times of invasion, as they gave small armies the ability to stop much larger invading armies long enough for the king to rally a defending army.Had few, if any titled aristocrats or gentry, living within its own borders. Outside the city walls, the land-owning aristocrats and gentry were the ruling class, but in most cases, they had no power within the city walls.

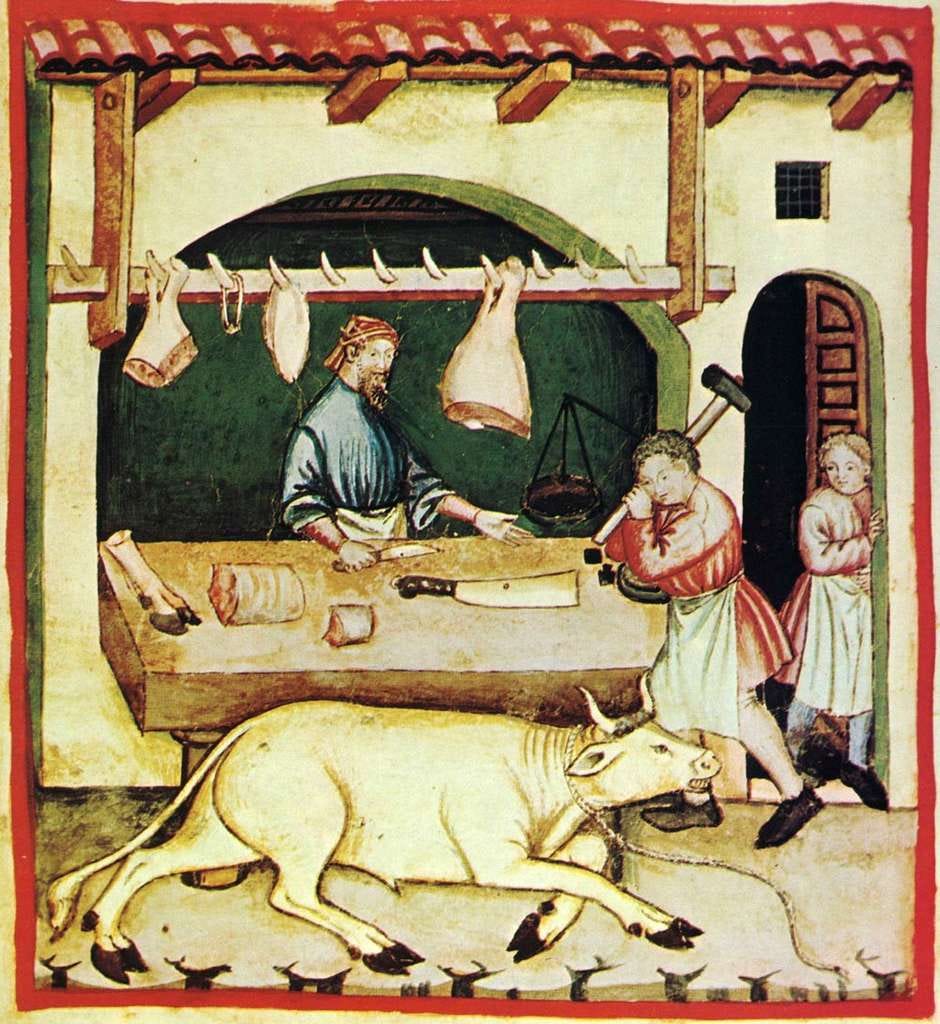

A large number of merchants and artisans. While the countryside was dominated by serfs, a tiny number of artisans in villages, and lords running the show, medieval cities were dominated by merchants and artisans. The artisans manufactured the goods, while the merchants distributed them.

A market for trading agricultural goods from the local countryside and locals crafts made within the city. The market was probably the most important location in the medieval city. It functioned as the distribution system for food and goods within the local area. Farmers typically brought their surplus agricultural goods via horse-drawn wagons to the weekly market. This enabled city dwellers to buy their food for the week, and farmers to buy tools and traded goods. This is the origin of today’s “Farmer’s Markets.”

A port to facilitate water transportation over rivers and oceans. While not all Medieval cities were on a river, the largest were. Before the invention of the railroad, shipping was by far the most cost-effective means to transport goods. The port was the medieval city’s link to the rest of the European economy.

A bridge and roads to facilitate land transportation. Large and middling cities were typically sited in locations where the river was wide enough to permit shipping, while still narrow enough to build a bridge across it. This enabled the city to become a hub for both water and land transportation.

Guilds (something like a labor union for artisans). Along with the markets and merchants, the guilds were key economic institutions. Typically artisans within one occupation were organized into guilds. The guilds regulated prices, enforced quality standards, facilitated training of apprentices, and provided a safety net for its members. The leaders of guilds often played an important role in the town council.

A constant stream of peasant immigrants from the local countryside looking for employment.

Despite being centers of economic dynamism and innovation, medieval towns were death traps. With no sanitation facilities and little knowledge regarding curing or preventing diseases, medieval cities had very high death rates even compared to serfs in the countryside. Without a steady stream of peasants immigrating into the city, the population would have spiraled downward.

Medieval cities functioned as underground railroads of their day. The peasants had a strong incentive to flee their farms because their lord had no powers within the city walls. Most cities had rules that escaped serfs became free within a certain amount of time (typically one year plus one day). This was particularly appealing to young men without land, as they could become day laborers in the city and perhaps get an apprenticeship with an artisanal master.

”City air makes you free” Wherever prosperous cities emerged, feudal obligations tended to be reduced. This process occurred long before the serfs were officially freed by the government.

So we can see from all the above that Medieval cities were completely different from the surrounding countryside. Medieval cities were little islands of modernity within the oceans of Medieval Europe.

So why did the lords agree to this?

You might ask yourself, why would lords allow these Medieval cities to be established if they negated his power and encouraged his serfs to escape? The answer is simple: money. Local nobles found these charters to be expedient because they could raise more revenue from a prosperous city than from a stagnant rural area.

There is only so much taxation that a feudal lord can get from Medieval farming practices. Once Medieval farming practices reached a tipping point, trade became more profitable.

As we have already seen, Medieval farming practices roughly doubled farming productivity. Since the amount of food that a farmer’s family needed to eat was relatively stable, this radically increased the food surplus. By about 1000, the food surplus was large enough to facilitate trade in the food surplus.

Medieval cities in Europe were usually established by a charter (or town constitution) from the local noble between 1000 and 1250. Very few were established after 1350. Not by coincidence, this was when Medieval farming practices were reaching their peak. Lords gradually learned that they could get more revenues from urban trade than taxing their local lands. In order words, they learned that getting a tiny cut of Medieval trade was better than a much bigger cut from the food production from their own land.

So Medieval lords decided to allow the formation of an autonomous city within a tiny portion of their lands in return for a much higher taxes each year. From 1000 to 1250, this was a great deal for feudal lords, so the practice spread rapidly. It started first in Francia, the heart of Medieval farming, and then spread to much of Northwest and Central Europe.

Medieval cities created competition

But as the practice spread, the feudal lords learned that they needed to offer the best terms possible. Merchants, artisans and farmers could pick the city that gave them the best offer. This was particularly true in Central Europe, where the local lords needed to lure in German immigrants to settle sparsely-populated areas. So under serfdom, the lords made competition illegal, but when Medieval cities got going, the lords accidentally created intense competition between towns and lords.

The situation got really bad for feudal lords during the 1300s. A massive wave of wars, famines, and epidemics wiped out a huge portion of the peasantry. Suddenly, feudal lords did not have enough farmers to farm their fields. At the same time, cities with their promise of freedom dotted the countryside. Under these conditions, lords had no choice but to compete with each other to lower feudal obligations to their serfs. Feudal lords gradually dismantled their own privilege, though the process was very incomplete well into the 19th Century.

The Empire Strikes Back

An even larger danger came from monarchs who leveraged the new technology of cannons and their taxing power to create powerful royal armies. European history from 1400 to 1800 was dominated by the struggle between centralizing monarchies and aristocrats/gentry who struggled to maintain their power.

By 1800, the centralizing monarchs won in almost every kingdom (with Poland and Britain being notable exceptions). The monarchy ultimately won power by integrating formerly independent lords into:

Centralized royal bureaucracy

Royal army

The Church (which most kings had the power of appointment over)

In return for giving up their autonomy, the monarchy promised the lords to maintain the feudal obligations of peasants to their lords. The lords chose money and status over their freedom (though the king’s artillery trains helped persuade them).

By 1700 the once-dominant feudal land-owning class were now dedicated servants of the king. But those feudal lords left behind a legacy of autonomous Medieval cities that transformed European society and world history. A tiny minority of these Medieval cities grew into full-fledged Commercial societies, which invented human material progress.

For that, we can thank the Medieval lords who were just trying to make a buck.

Want to learn more?

If you are interested in learning more about Medieval European cities, I recommend that you read the following summaries in my library of online book summaries:

You can also read more articles on related topics:

These essays are fabulous, thank you! I learn something in every one of them.

Would you consider doing an article on any of the following topics -

1) History of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Export Processing Zones (EPZs) in Asia and their role in promoting investment and industrialisation.

2) If a startup wants to build a charter city in the 21st century, what will be their minimum viable product?

3) Potential impact of new transportation technologies on existing and new cities. Technologies include EVs, self driving vehicles, remote work, eVtols, airships and underground delivery networks etc.

4) Could charter cities undermine the authority of the clans and their chiefs in Sub Saharan Africa as it did for feudalism in Europe?