Over the past year, I have read many media and academic predictions that “2024 is the year that we could/will hit Peak Coal.” Here is just one example. You can easily find more with a quick internet search.

As someone who has followed the energy industry for decades, this brings back memories of false predictions of “Peak Oil” and “Peak Natural Gas.” All of those predictions seemed plausible at the time, but then the energy industry broke new records in production.

Most of these predictions were based on similar assumptions to Hubbert’s Peak. M. King Hubbert was a highly respected geophysicist who devised a theory for predicting when a nation’s crude oil production would peak. He successfully predicted crude oil production peaks in many nations. Because my father is a petroleum geologist for the US Geological Survey and we have often spoken about energy issues, I was very familiar with Hubbert’s Peak. For a long time, I thought that Hubbert was correct.

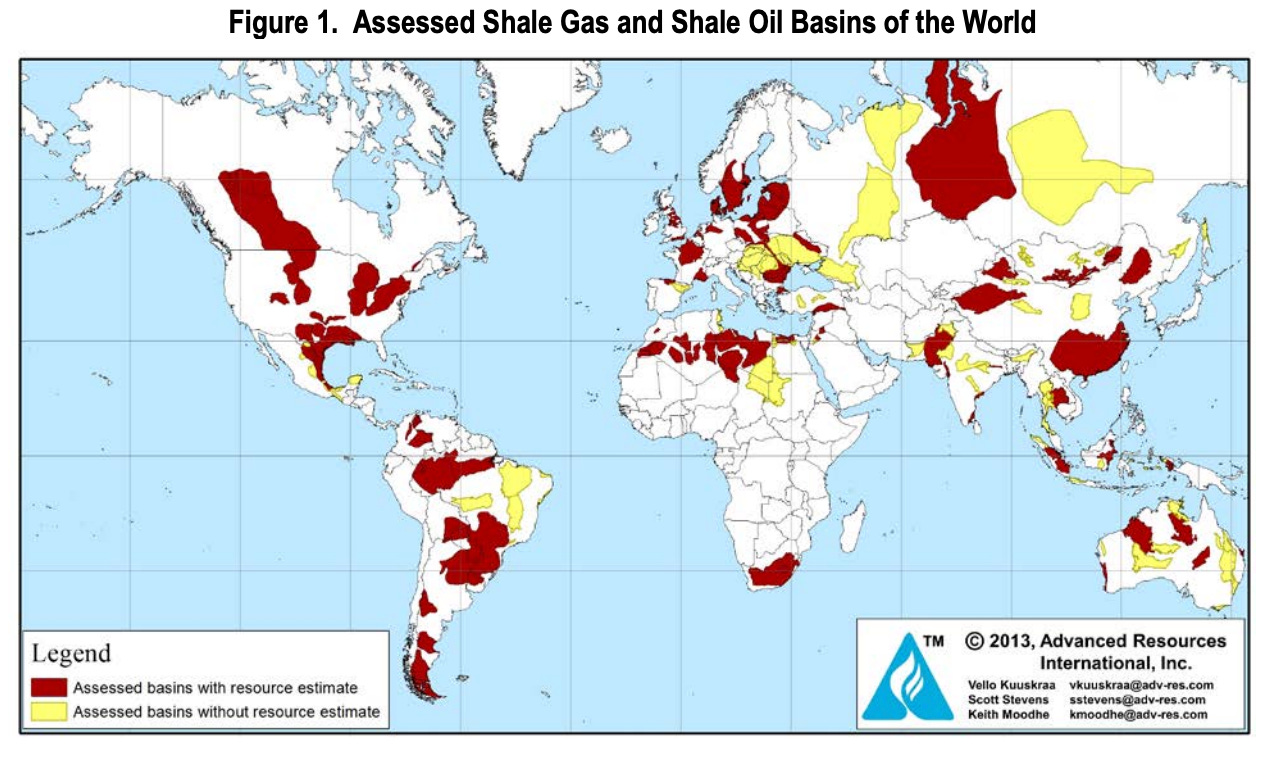

If you had asked me back before 2005, I would have agreed with those predictions of Peak Oil within a few years, but then the Shale boom blew those predictions out of the water. Now I realize that transformative energy technologies can make long-existing trends obsolete.

For Shale drilling, those technological innovations were:

horizontal drilling

multilateral drilling

hydraulic fracturing

micro-seismic imaging

sliding sleeves

3D computer modeling

polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) drill bits

The combination of those technologies made the impossible possible. You can learn more about the Shale industry in my other article.

While global fossil fuel consumption keeps increasing at a rapid rate, it is possible that we are at or near “Peak Coal” (by that, I mean gross annual global coal consumption tops out). Just because past predictions of “Peak Oil” and “Peak Natural Gas” were incorrect does not mean that current predictions of “Peak Coal” are also incorrect.

Here are a few pieces of evidence that we might have be at or near “Peak Coal.”

Global coal consumption has been relatively flat since about 2009

North America, Europe, and Australia are rapidly phasing out coal.

Latin America and Africa have relatively low levels of coal consumption and that does not seem likely to change (unless those regions experience transformative economic growth).

Outside of Asia there are very few new coal plants being constructed.

The Chinese economy (by far the biggest coal consumer in the world) has experienced far slower economic growth rate since the start of the Covid pandemic. This seems likely to be a permanent decline in their economic growth rate.

Chinese coal plants are running at lower capacity (i.e. many coal plants are shifting from 24/7/365 baseload production to rapidly starting and stopping coal plants to balance electricity supply and consumer demand).

The Chinese population is clearly in decline.

Given their fertility rate, it is very likely that China’s demographic decline will accelerate in the coming decades.

China has embarked on a vast expansion of solar and wind production. This opens the possibility that solar and wind will reduce coal consumption, or at least reduce its increase.

See also my other posts on Energy:

You might also enjoy reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

While I think it is quite possible that global coal consumption will not increase in the future, I am very skeptical that this will lead to a substantial decline (say 30-50% in the next 20-30 years). Here are a few indicators that make me skeptical:

China is still constructing new coal-burning power plants at a rapid rate. While it is possible that they will never actually combust coal in them, this seems unlikely. The reason why China might never combust coal is because so many previous Chinese industries have vastly overproduced consumer demand (real estate and high-speed rail are just two examples) - a problem with debt-financed expansion.

India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Turkey, and other Asian nations are constructing 1085 (!) coal-burning power plants (that number includes China). Coal consumption is extremely likely to rise in those very populous nations.

My guess is that South Asia and Southeast Asia are going to experience transformative economic growth in the coming decades. Essentially, for both national security and industry shifting to nations with cheaper labor, the center of global manufacturing seems likely to shift from China to South Asia and Southeast Asia.

This economic growth in South Asia and Southeast Asia will require a massive increase in energy, particularly electricity.

The combined population of these two regions is roughly double China’s alone, so it will have a serious impact on global coal consumption.

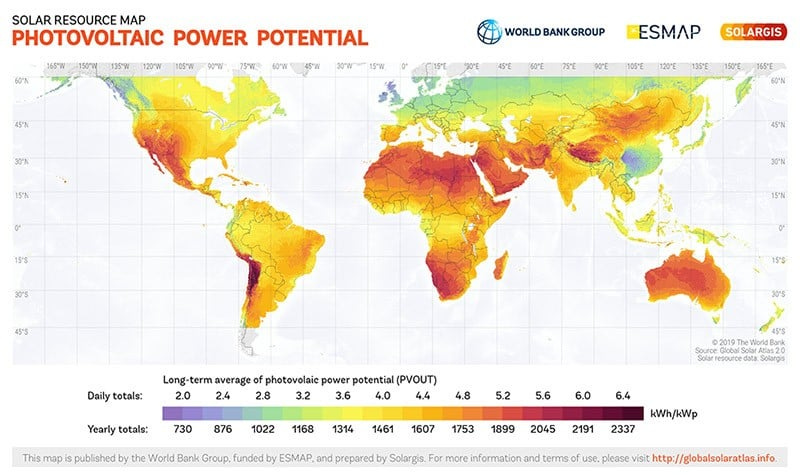

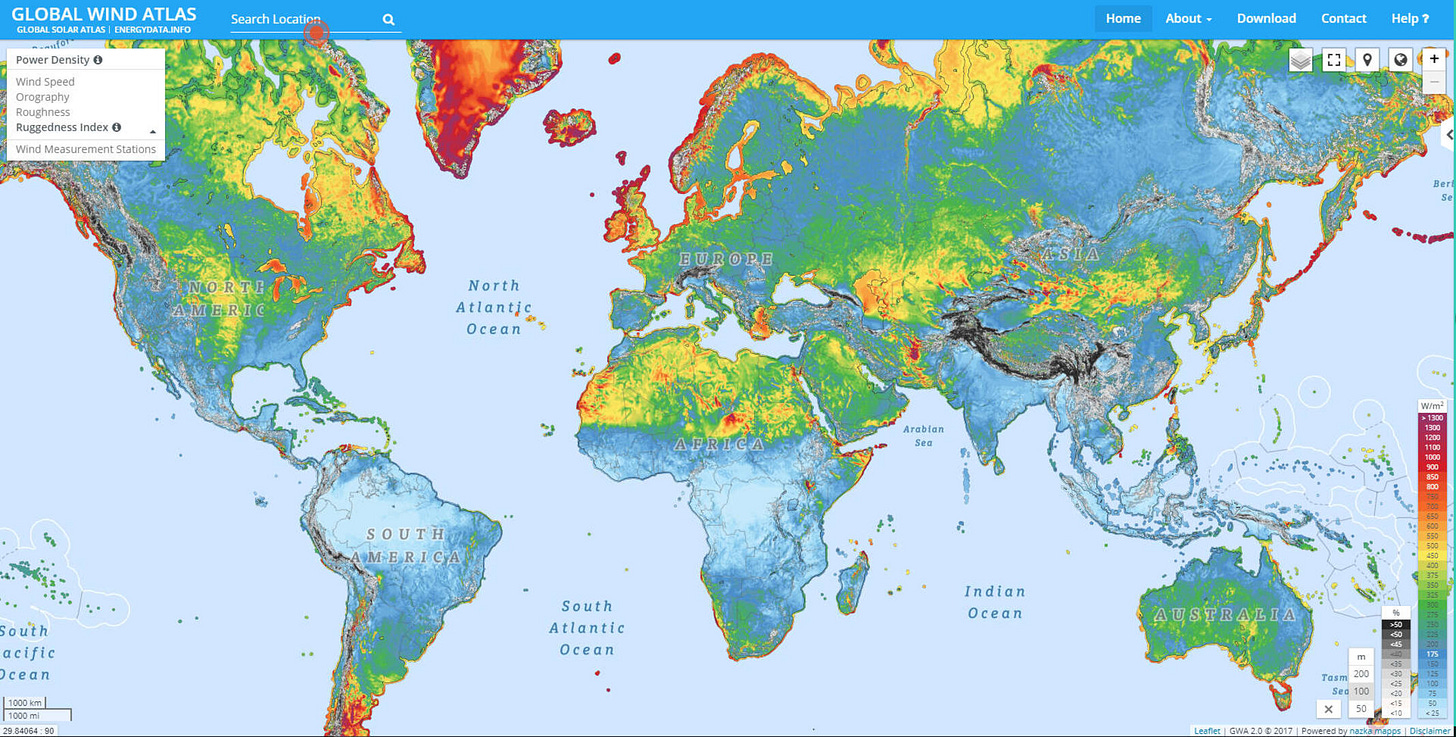

South Asia and Southeast Asia will have few alternative energy sources to coal. Those regions have very low wind or solar resources, and likely cannot afford to construct nuclear power plants at scale. Increased hydroelectric will probably play an important role, but likely far less than coal.

While South Asia and Southeast Asia nations can construct solar and wind plants, those structures will generate relatively little electricity, and the amount of electricity generated will vary greatly over time. This means that the electricity generated will not match consumer demand. These regions cannot afford to construct utility-scale batteries to store that electricity for later use.

So, realistically, these nations must choose between coal, hydro and natural gas for their electricity needs. And oil will be used for transportation unless electric cars drop dramatically in cost.

While these regions have significant amounts of Shale fields that yield oil and natural gas, these nations currently do not have the organizations and skills to exploit those fields. Without assistance from the United States, it is far cheaper to burn coal in South Asia and Southeast Asia than natural gas or hydroelectric.

So the big question is:

Will increased coal consumption in South Asia and Southeast Asia (and maybe China), offset declining or absent coal consumption in the rest of the world?

To be honest, I really do not know. We have three powerful and opposing energy trends (China, South/Southeast Asia, and the rest of the world), and it is difficult to predict which trend will have the most significant impact on global coal consumption.

If I am forced to predict, I think that we have hit another false peak in global coal consumption (like 1989-98), and global coal consumption will increase again in the subsequent decades. I do think, however, that this future increase will likely be significantly less than the upward trends before 1989 and from 1998 to 2008.

I am also confident that we will experience “Peak Coal” sometime in the 21st century, but this will likely not be due to Green energy policies. The timing of Peak Coal is likely far more dependent on:

How quickly Shale gas technologies, skills, and organizations spread from the USA to the rest of the world.

Since natural gas is the only fuel source that can substitute for every use of coal, and it is technically possible now, it is only a matter of whether nations can extract enough natural gas to make the fuel costs competitive with coal in all regions. Natural gas plants are already cheaper than coal plants (or any other electrical producer). It is just a matter of increasing natural gas supply to lower costs.

If Share gas technologies, skills, and organizations spread rapidly in the 2020s, we will hit “peak coal” much sooner, and global carbon dioxide emissions and pollution will be much lower. Global Netzero by 2050 will still be impossible, but we will get a lot closer to that goal.Whether the Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) industry can lower fuel costs to be price competitive with coal. LNG is natural gas that is cooled down to approximately −162 °C (−260 °F) so that it becomes a liquid. Liquids can easily be transported on ships to any LNG port in the world. This makes it possible to distribute natural gas to nations that are not connected via natural gas pipelines.

Currently, there is a significant price premium for LNG over traditional natural gas, but if that price premium largely disappears, then natural gas can become price competitive with coal across the world. This would make the LNG industry much like the crude oil industry (one market price across the globe).

This will be very difficult, but it is not impossible.Whether the nuclear power industry will be able to lower construction costs to a level where it is price-competitive with coal. Right now, coal is dramatically cheaper than nuclear, but an unregulated nuclear industry may be able to dramatically cut costs via production at scale.

This will also be very difficult, but it is not impossible.A transformative energy technology is invented that makes all current energy technologies obsolete. This is guaranteed to happen at some point, but it could take many decades for the initial discovery and many more decades for deployment across the globe. If it happens, it will be the most significant technological innovation of the 21st Century.

I have a plan for making it happen sooner rather than later.

Green energy technologies are likely to have minimal effect on Asian coal production. Regardless of the above, I believe that getting to Global Netzero by 2050 is impossible. And I seriously doubt that solar and wind alone can get there even by 2100. The four options listed above are far more likely to get to Global Netzero by 2100 and Peak Coal long before then.

See also my other posts on Energy:

You might also enjoy reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Here are some more great energy-related Substack columns that you might be interested in: