How developing nations can create competitive export industries

And ratchet their way from poverty to progress

In previous articles, I made the case that most Western development theories are not very useful for developing nations. Reforming institutions, begging for more foreign aid, promoting democracy and human rights, and sustainable development are all very unlikely the create long-term widely-shared economic growth.

In the previous article in this series, I made the case that developing nations should focus their scarce resources on creating higher-value-added export industries to inject wealth into their nation. The question that I want to answer today is:

How do developing nations do that?

The following is an excerpt from my book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order e-books at a discounted price on my website, or you can purchase for full price on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can read other articles on developing nations, including:

Why developing nations are still poor:

What wealthy nations can do to help developing nations:

What developing nations can do to help themselves:

A Viable Export Strategy

Developing nations should learn to implement Hidalgo and Haussmann’s analogy that I mentioned in the previous article: think like a monkey who wants to move from one side of the forest with a few bananas to the other side of the forest with many bananas, while not going hungry along the way. I particularly recommend that government officials, entrepreneurs, engineers, and venture capitalists in developing nations learn to think that way.

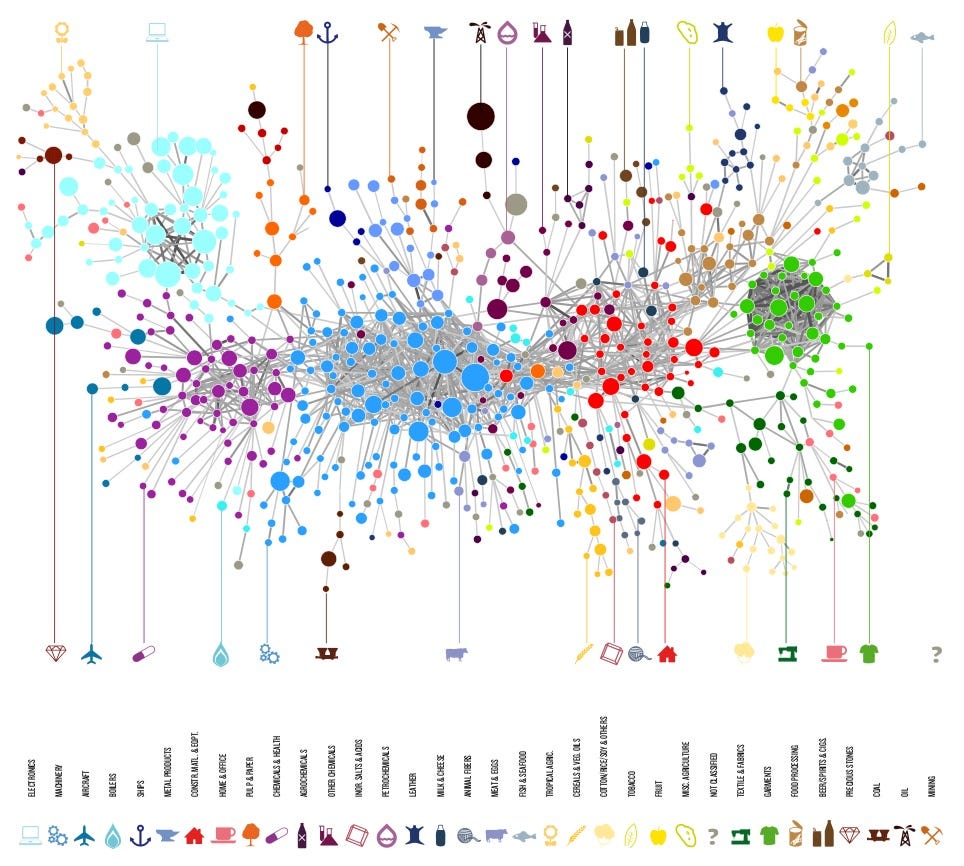

I recommend that anyone who lives in a developing nation read their book: The Atlas of Economic Complexity (my summary of this book) and study the companion website (unfortunately since the publication of my book much of this website is now pay-gated and reorganized). The section for each nation that is currently labeled “Country Profiles” reveals economic statistics that are more actionable, timely, and specific than I have seen anywhere else.

The most relevant section for each nation is currently entitled “New Product Opportunities.” This section lists all of the industries that their theory predicts that the selected nation should invest resources in promoting. The site does not explain exactly how to do so, but I hope that as their theory attracts more attention from developing nations, they can gradually learn how to do so by trial and error.

As I mentioned in my previous article, the logic of this viewpoint leads to a clear economic learning strategy for developing nations:

Identify all your existing domestic industries.

Identify other industries that are closely related to existing industries and which also produce equal or higher added value.

Leverage the necessary technologies, skills, organizations, and capital from existing industries to learn the skills needed for the new industry and use the advantage of cheaper labor to outcompete richer nations. This will often involve selling an existing product at a cheaper price than richer nations can produce it for. It also involves focusing on the low end of the market, where price is more important than quality, while leaving richer nations to focus on the higher end of the market.

Keep repeating the process for decades.

Now let’s get into to the details of how leaders of developing nations can actually do this. A reasonable starting point for a long-term development strategy via exports would include:

Select a few industries recommended by the website to focus on. These are industries that are similar to pre-existing export industries with a higher potential for profitable export. Because they are similar to existing industries, the potential for “jumping” to that industry successfully is much higher.

Collate all information that is currently available on the internet about the knowledge and skills that are needed within the target industries.

If necessary, translate that information into the native language.

Publish that information onto one website, so citizens of their nation can easily find them.

Organize conferences and networks of managers, entrepreneurs, engineers, skilled workers, and venture capitalists who have a detailed knowledge of the existing adjacent industries within their nations.

Focus the discussion on what those actors already know about the current industry, and how they might leverage that knowledge and skills to apply in the new target industry.

Identify “missing skills” that the nations do not have but need to grow the new target industry.

Pay foreign industry experts to give lectures, write articles and create videos that specifically address the needs of both the target industry and the nation in question. A particular focus should be on the missing skills.

Provide venture capital to entrepreneurs who are willing to found new companies in the target industry.

Provide seed money to establish local venture capital companies, so that funding sources can shift from the government to private equity in the long run.

Continue that funding for a few years, but then make further funding based upon clear, transparent export metrics. If other citizens of other nations are willing to buy a company’s product, that company must be doing something right. This gives evidence for a further round of funding. If not, funding should be cut off.

Pay foreign industry experts to provide on-the-job training to new employees. In the past, this required them to relocate to foreign countries, but short visits and digital conferencing may now be an adequate substitute. These meetings should “train the trainer” so that, after a local employee gains the necessary expertise, they could then do face-to-face training with other employees on site.

Establish departments within public universities and secondary education that are specifically designed to teach critical skills to future entrepreneurs, engineers, skilled workers, and venture capitalists. Most likely, foreign experts will be needed for instruction, at least at the start. As the economy changes, this curriculum should be constantly updated to reflect those changes.

Keep experimenting. It will take time to learn what works.

Compare notes with other developing nations who are trying similar strategies, to learn what they learned.

According to the other schools of thought that I discussed earlier, none of this is necessary because these efforts are not focused on what matters. But I do not believe that free trade, fighting corruption, or establishing property rights will help developing nations build profitable export industries. Nor do I believe that foreign aid for education, sanitation, and health care will do so; nor will democracy, political rights, or sustainable development. None of the other proposed strategies are focused enough to make a difference in what matters: higher value-added export industries.

My proposed strategy also has many important advantages over the competing proposals coming from the other schools:

It leverages the money, knowledge, and skills of wealthy nations without requiring consent from their governments or multilateral organizations.

It does not require massive reform of institutions or constitutions.

It does not require foreign aid or large amounts of domestic funding.

It does not require a massive transition to democracy and freedom.

It does not require many different departments to cooperate.

It does not threaten authoritarian leaders who run the nation (more on this later).

It is the only strategy that focuses on the Five Keys to Progress.

Whereas the other proposals require some sort of agreement from domestic political leadership, multilateral organizations, or foreign governments, one small department with a relatively small budget can implement my proposal. This gives it a huge advantage over the other proposals.

It is quite conceivable that one particularly energetic Minister of the Economy or lower-level official within the same department might be able to start the process without much budget or approval from above.

Most of my proposal involves figuring out what needs to be learned, learning those skills, and then getting the right people together to coordinate their actions. Depending upon the industry at hand, initial seed money may not need to be extravagant.

High-level leaders may prefer not to know too many of the details of what is going on so that they can rely on plausible deniability if it all fails.

I believe that developing nations should focus on perfecting this strategy to gradually build higher-value-added export industries that are competitive on the world market. This strategy will enable developing nations to gradually leverage all the existing technology, skills, organizations, and capital to build new industries.

Over decades, this process can build a thriving economy that experiences progress. So many nations have transformed themselves within one generation that I refuse to believe that it is impossible.

There are two important problems with my proposal: the most important is that, because it has never been tried before, it might well fail. Failure is the most likely outcome of all new experiments, but that does not mean that one should not try.

We know that nations have made the transition from poverty to progress, so something works. And by thinking through how previous nations did do (as opposed to listening to the theories and ideologies of other schools), developing nations might be able to radically speed up the process.

With the proper knowledge and the right people, evolutionary processes can be accelerated. That is exactly why understanding the real causes of modern progress in wealthy nations is so critical.

So, have other nations used my proposed strategy? No, not if you focus on the details. But I think that if you look at strategies that Commercial societies in Northwest Europe used, what European nations used to industrialize in the 19th Century, and what Asian nations did at a later date, I believe that there are strong resemblances.

Because historical societies did not have the benefits of the theory of economic complexity, nor its associated books and websites, they were forced to rely on the idea of ratcheting up export industries via “learning by doing”. I have every confidence that current developing nations can get even better results with the help of those critical resources.

Moreover, based upon a study of history, it is plausible that previous nations followed a similar strategy without necessarily being clear in their minds as to what they were doing. They may have just solved one problem at a time, copied others, and gradually worked their way through my proposed list without realizing it.

Because they did not do this regularly within a relatively short period, there was no reason for national governments to develop a formal methodology. And each of these nations, feeling that they were in competition with all the others, had a strong reason not to enlighten the rest of the world, let alone publish it in a book as I do.

Note: If you are interested in doing a deeper dive into the theory of Economic Complexity, I would recommend that you start by reading the following summaries from my library of online book summaries in the following order:

“Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity” by Hausmann, Hidalgo et al

Observatory of Economic Complexity (this is a free online website displaying data related to economic complexity)

“The Product Space Conditions the Development of Nations” by many

“Economic Development as Self-Discovery” by Hausmann and Rodrik

“Discovering Southern and East Africa’s Industrial Opportunities” by Cesar Hidalgo

“Shooting High or Low: Do Countries Benefit from Entering Unrelated Activities” by many

“Linking Economic Complexity, Institutions and Income Inequality” by Hartmann, Hidalgo et al

What Does the Great Leader Think?

The other problem with my proposal is that some authoritarian leaders and all totalitarian leaders would never accept it. Lower-level officials might try it on their own initiative thinking that “this is what the Great Leader would want if only I could talk with him.” But once their superiors found out about these attempts, they would squash the effort.

High-value export industries create wealth. Authoritarian leaders want to monopolize as much wealth as they can and then redistribute most of it to supporters with a particular focus on security services. This is how authoritarian regimes maintain their power. As strange as it may sound to rich Westerners, many leaders do not want productive wealth in the parts of the economy that they do not control.

Ultimately it comes down to the individual preferences of the leader and their highest-level supporters. They might feel threatened by my proposal, and they might not. Remember, they are trying to balance a desire to not let rival power bases emerge with the need to promote economic growth to maintain their legitimacy. Individual leaders will have different preferences, and those preferences will vary over time.

While I am sure that many authoritarian and all totalitarian leaders would ruthlessly suppress any hints of implementing my proposal, I believe that most leaders in developing nations would not. And some leaders might enthusiastically support it. So while my proposal may not work for every developing nation at all times, I am confident that it can be put into practice by more than a few nations.

The beautiful thing about my proposal is that it is flexible enough to apply to all developing nations (and probably wealthy ones too), and it is self-sustaining. If a nation gets real results by establishing one new export industry, this builds political support for trying the methodology out on another industry.

Success in building one industry also leads to learning, so hopefully, nations will get better at it with each try. With each victory, the department that oversees the effort will get more and more political legitimacy and bigger budgets (assuming the highest leaders like the effort, of course).

Better yet is the effect on the rest of the economy. Employees in high-value export industries will probably earn higher than average incomes. Those employees will spend money in the local economy and provide markets for small local businesses.

The tax base would also be broadened. Some of the revenue will undoubtedly be stolen by corrupt officials or wasted on useless programs, but some of it might be used for investing in infrastructure, sanitation, health care, and education. Either way, the money coming in will get support from at least some actors, corrupt or not.

Most importantly, the nation will learn valuable skills, implement new technology, start up new institutions and get new sources of working capital. All of this can then be used for starting the next industry. If properly implemented and maintained, it could create many competitive exporting industries in a relatively short period.

The above was an excerpt from my book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order e-books at a discounted price on my website, or you can purchase for full price on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can read other articles on developing nations, including:

Why developing nations are still poor:

What wealthy nations can do to help developing nations:

What developing nations can do to help themselves: