Why Developing nations need to create thriving export industries

And why they should focus their scarce resources on doing so

In previous articles, I made the case that most Western development theories are not very useful for developing nations. Reforming institutions, begging for more foreign aid, promoting democracy and human rights, and sustainable development are all very unlikely the create long-term widely-shared economic growth.

Wealthy Western nations can help developing nations by:

But let’s face it. There is only so much wealthy Western nations can do to help.

So how can developing nations ratchet themselves up from poverty to progress?

Using the concept of the Five Keys to Progress, I narrowed down the list of necessary preconditions for material progress to identify what developing nations are missing:

Key #1: A highly efficient food production and distribution system. With the exception of Sub-Saharan Africa and a few other nations, most developing nations have productive enough agriculture to feed themselves. Thanks to the global trade network, they can supplement their domestic food production with imports.

Key #2: Trade-based cities packed with a large number of free citizens possessing a wide variety of skills. Fortunately, virtually every developing nation has large cities and the trend towards urbanization seems inevitable.

Key #3: Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. Except for a few hardline totalitarian nations, such as North Korea, there is already enough non-violent competition between institutions to get the ball of progress rolling if all the other conditions apply. Fortunately, there is no evidence that nations need democracy, free markets or good institutions in order to start progress.

Today I want to make the case that the most important goal for developing nations is to create thriving export industries (Key #4) that can compete in the global market. It is only in this way that they can inject wealth into their local economies.

The following is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order e-books at a discounted price on my website, or you can purchase for full price on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can read other articles on developing nations, including:

Why developing nations are still poor:

What wealthy nations can do to help developing nations:

What developing nations can do to help themselves:

Regardless of how productive agriculture, energy systems, or innovative cities are, for progress to take place, a society must have at least one high-value-added industry that exports to the rest of the world. These industries inject wealth into the region and accelerate economic growth. Other than expanding energy usage, I believe this is by far the most effective strategy that developing nations can implement to initiate progress and keep it going.

For current developing nations, I would reword the general principle a bit to “having as many export industries as possible, and each of those industries should be as high-value-added as possible given the current state.” The wealth created by high-value-added export industries can then be spent locally by its employees, generating demand for a gaggle of smaller local businesses. This wealth also creates a steady revenue stream for governments to invest in education, health, transportation, sanitation, and energy infrastructure.

By exporting to the rest of the world, an industry radically increases the potential demand for its goods. Except for the United States and perhaps China, no nation has the domestic demand necessary for large-scale industry without exporting to the rest of the world.

If a farm or city is restricted to customers within its borders, its economy has far less growth potential. And the more value the industry generates, the higher the potential profits. That is why high-value-added industries that are competitive enough to export to the rest of the world are so critical to promoting progress within a region.

The nature of the industry that is needed varies greatly over time. In the distant past, a mineral or crop might have been sufficient. More typically today, it requires some form of manufacturing. Textiles, steel, and consumer electronics are all industries that played critical roles in various nations during their initial industrialization.

To successfully export, a city needs the necessary technologies, skills, social organizations, and capital. These factors are typically acquired by copying them from richer regions that already have them, modifying them for the local environment, and then slowly learning by doing. Skilled immigrants from richer nations often play a critical training role in the learning of new skills.

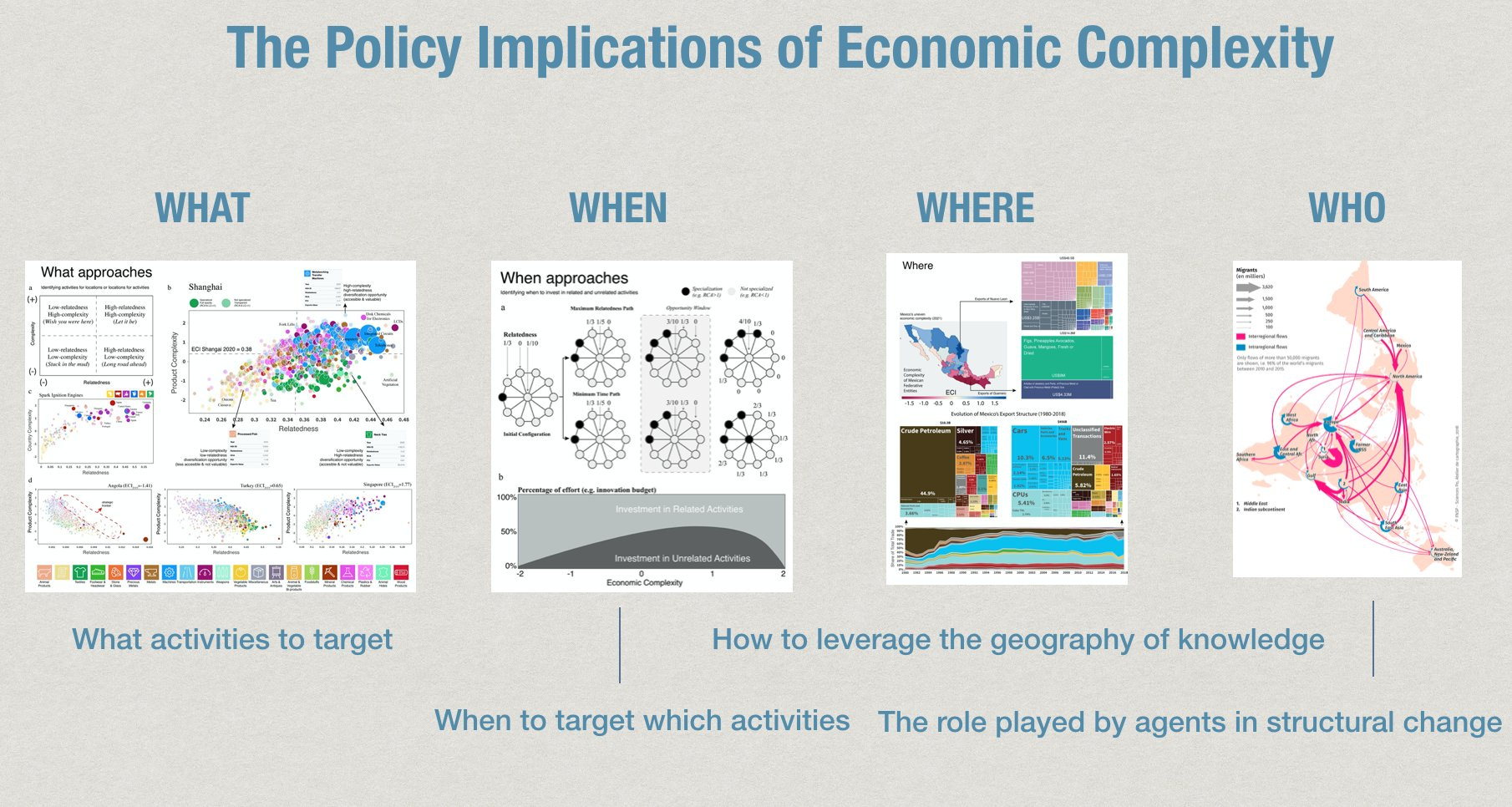

The emerging discipline of Economic Complexity gives us the best understanding of how this process works. Cesar Hidalgo and Ricardo Hausmann have played pioneering roles in this field. Hidalgo and Hausmann argue that modern societies acquire productive knowledge by distributing that knowledge among many specialized workers. Organizations and markets then combine that knowledge to make useful products. This fits in nicely with my observations about How Progress Works.

If you are interested in doing a deeper dive into the theory of Economic Complexity, I would recommend that you start by reading the following summaries from my library of online book summaries in the following order:

“Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity” by Hausmann, Hidalgo et al

Observatory of Economic Complexity (this is a free online website displaying data related to economic complexity)

“The Product Space Conditions the Development of Nations” by many

“Economic Development as Self-Discovery” by Hausmann and Rodrik

“Discovering Southern and East Africa’s Industrial Opportunities” by Cesar Hidalgo

“Shooting High or Low: Do Countries Benefit from Entering Unrelated Activities” by many

“Linking Economic Complexity, Institutions and Income Inequality” by Hartmann, Hidalgo et al

The skills needed for industries can only be taught face-to-face. Typically, people learn through face-to-face guidance from people who have already mastered the skills. This makes knowledge transfer across long distances very difficult.

And transferring some of the necessary skills for an export industry is not enough. An export industry needs all the necessary skills. If an industry is missing only one key skill, it cannot be competitive.

This places poorer nations in a Catch-22 situation. They cannot create high-value-added industries until they acquire the necessary skills, but they cannot acquire the necessary skills until they already have a functioning industry. This creates a fundamental gap that developing nations have difficulty bridging.

On the face of it, this appears to make economic growth impossible. Fortunately, we know from history that economic growth is possible.

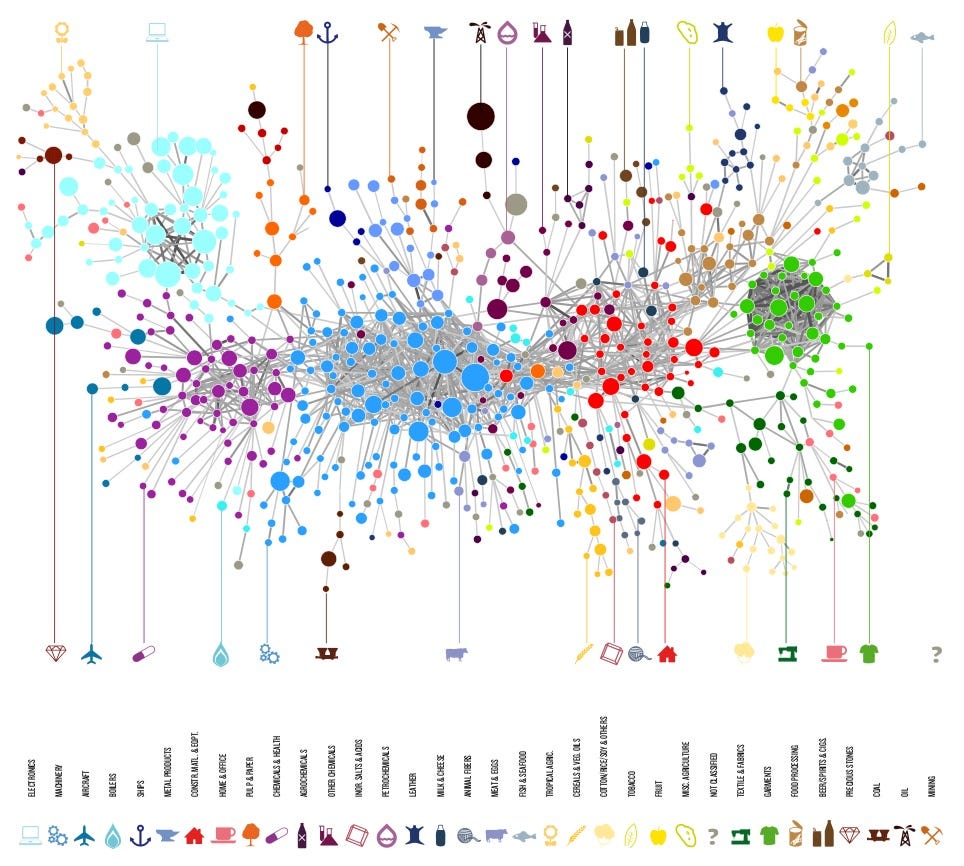

The theory of economic complexity gives us the key intellectual breakthrough that industries are related to each other because they share common skills. For example, manufacturing shoes is closely related to manufacturing hats, because they share common production skills. Those same industries are far less related to manufacturing tractors or pharmaceuticals because those industries require very different skills.

And skills are not the only factor. Related industries also require similar technologies and organizational needs. This makes it theoretically possible for poor nations to leverage the limited knowledge that they have from current sectors of the economy to other related sectors that offer higher value.

Voyage of the Monkey

Hidalgo and Hausmann use the analogy of a monkey traveling through a forest in search of food. The monkey is on one side of the forest with few bananas (limited export options) and wants to get to the other side of the forest with many bananas (many profitable high-value-added export industries). The monkey can only travel one branch at-a-time, and it must survive each step by consuming bananas (i.e. acquiring the energy to survive).

So what does the monkey do? He gradually moves to the nearest branch with more bananas than the one he is currently on. He then uses the energy gained from the bananas (i.e. the technologies, skills, organizations, and capital) to go to the next branch. It is a long, slow process, but eventually, the monkey reaches the part of the forest with many bananas. This assumes, of course, that there are branches that are sufficiently close to each other along the way. Hidalgo and Hausmann’s breakthrough is that they show through sophisticated statistical techniques that there is a pathway of branches from one side of the forest to the other.

Hidalgo and Hausmann represent all existing export industries with the following Product Space map (you can think of this as the forest that the monkey needs to travel through):

This viewpoint gives us a clear understanding of how economies developed both in the past and the present. Commercial societies in northern Italy, Flanders, Netherlands, and England pioneered the innovations that created high-value-added industries. This was a long, slow process because they had no one to copy at first. There was a huge amount of learning by doing, with many mistakes along the way. As long as four of the Five Keys to Progress created the necessary preconditions for progress, they could keep experimenting and innovating for centuries.

Eventually, this led to the critical breakthrough of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. This largely involved the application of fossil fuels to the critical transportation, communication, agricultural, and materials sectors. Industrial technologies overcame some, but not all, of the geographical constraints on progress.

Today, developing nations face a different problem. All of the necessary technologies, skills, and organizations have already been invented, so they only need to copy them rather than creating them from scratch. However, because skills typically require a face-to-face transfer, it is hard for people in developing nations to learn everything they need to know. Worse, they face highly competitive industries in the richer nations that are vastly more productive. The one important advantage that developing nations have is cheaper labor.

The logic of this viewpoint leads to a clear economic learning strategy for developing nations:

Identify all your existing domestic industries.

Identify other industries that are closely related to existing industries and which also produce equal or higher added value.

Leverage the necessary technologies, skills, organizations, and capital from existing industries to learn the skills needed for the new industry and use the advantage of cheaper labor to outcompete richer nations. This will often involve selling an existing product at a cheaper price than richer nations can produce it for. It also involves focusing on the low end of the market, where price is more important than quality, while leaving richer nations to focus on the higher end of the market.

Keep repeating the process for decades.

It is a nice theory, but does it work? Hidalgo, Hausmann, and others give compelling evidence that economic complexity is a useful concept, but it is not yet clear whether it can be put into practice.

By statistical analysis, Hidalgo and Hausmann show that complexity explains 73% of the variation in income across 128 countries. They also show that the difference between national income and level of complexity is the single best predictor of future economic growth. In other words, poor countries that have established a beachhead in higher-value-added products experience much higher growth rates in the immediate future than those that do not.

Free Trade or Fair Trade?

For centuries there have been bitter economic debates between free traders who abhor industrial policy and economic nationalists who see tariffs as crucial for promoting national economic growth. Overall, I am convinced by the arguments of free traders that industrial policies often lead to bad economic outcomes by subsidizing failing companies and those with insider connections.

I believe, however, that the theory of economic complexity creates a compelling middle ground. Instead of government bureaucrats “picking winners” based on political pressures, let the economic data do so. If government bureaucrats are forced by law to only pick industries that comply with the above algorithm, this might greatly reduce corruption and incorrect guesses.

As I mentioned before, it is still very unclear what specific policies a government should implement once they have identified an industry. I do think further research and inexpensive experimentation are warranted in this area. The theory just makes too much sense to be completely wrong.

So how can developing nations implement this idea? That is the topic of my next article in this series.

The above was an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order e-books at a discounted price on my website, or you can purchase for full price on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can read other articles on developing nations, including:

Why developing nations are still poor:

What wealthy nations can do to help developing nations:

What developing nations can do to help themselves:

Thank you for a thoughtful reply. I agree that domestic VC can take the reins, which is ideal. Getting to that point is very difficult

Honestly it seems to me that you don't even need a government to get any of these done. A small set of entrepreneurs could kickstart this whole thing themselves and get funding from private actors all over the world. It doesn't seem that expensive nor does it seem to be so far reaching as to require the weight of government to enact,

Also if early wins are recorded, it can then become much easier to convince governmental actors to pitch in.