We need a Green Revolution 2.0 for Africa

And why Greens are trying to stop it from happening

In my book series and Substack column, I focus on the concept of the Five Keys to Progress. I believe that the Five Keys to Progress is an essential unifying concept for understanding human material progress. They are critical because they are the necessary preconditions for a society changing from a state of poverty to a state of progress, and they are actionable in today’s world. In other words, the concept not only helps to understand the world but also how to make it better.

I have already written several articles explaining how Northwest Europe achieved the first Key: A highly efficient food production and distribution system. This enables societies to overcome geographical constraints to food production so that large numbers of people can focus on solving problems other than getting enough food to eat.

Most of the following is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Food has been the critical constraint on innovation and progress throughout the vast bulk of human history. Over the last 10,000 years increasing food production per unit of human labor has been a key driving force in progress.

I know that this fact is very hard for modern readers to relate to, but it is true. Today when we are hungry, we go to the refrigerator or pantry. When the refrigerator or pantry is empty, we go to the grocery store. Easy, right?

Well, no. Not for our ancestors.

While getting enough food to survive is easy in modern societies, it was an epic task for our ancestors. For the overwhelming majority of our ancestors, the quest to acquire enough food to survive took up the majority of their waking hours. It was an obsession, and all of society was organized around the most effective means to do so within the local environment.

Before one can innovate, one must first survive. To survive, one must eat large amounts of food. If one has to spend the vast majority of one’s time focused on acquiring food, one cannot devote much time to innovating non-agricultural skills, technologies, and organizations. Our ancestors effectively traded time for food.

The vast majority of mankind devoted the bulk of their waking hours to the quest to produce enough food to eat. Very gradually over time, they innovated new technologies, skills, and processes that enabled more effective means of producing and distributing food. This quest for food production was so all-encompassing that we can categorize entire societies by how they did so.

This quest for food greatly affected where we lived. Until the last few centuries, humans had to disperse geographically to acquire food, because the subsistence technology of the day was not productive enough for one family to grow enough of a food surplus to support urban populations. The endless drudgery of acquiring food has stifled the human potential for innovation and progress for millennia.

There is only so much food that can be acquired from any one acre of land with simple technology. With technological innovation, we have been able to radically increase this amount, but for any given natural environment and a suite of technologies, there is a fixed amount of food that can be produced per acre.

So humanity dispersed to survive. They had no choice. Survival comes first.

But this dispersal undermined the ability of large numbers of people to interact regularly. Dispersal made it harder to copy technologies, skills, and organizations. With far fewer models to copy, innovation and diffusion were far slower than they could have been.

To make things worse, the type of food that can be produced in any specific area is highly constrained. In some regions, fishing or hunting marine mammals is possible, but not in most areas. In other regions, hunting big game is possible, but not in most areas. In some areas, cultivating rice is possible, but not wheat or corn. In other areas, cultivating wheat is possible, but not other staple crops.

Since food production and distribution is not something that one individual can do, the entire society had to be sculpted around the type of food that could be produced. Technologies, skills, organizations, and values of societies were all greatly affected by what type of food could be produced in their geographical environment.

What is more, each one of these food types had very different amounts of energy and nutrients relative to the human work effort. This meant that some societies had huge advantages over others, simply because they lived in regions with the most cost-effective food sources.

Some geographical regions simply could not support much food production, so they doomed their residents to be trapped in poverty. Fortunately, there was one important exception to this rule: Northwest Europe and the regions settled by Northwest Europeans. While other agricultural systems hardly changed for thousands of years, these regions have undergone many transformations. Each of these transformations resulted in a significantly increased food surplus per family of farmers.

As I document in my first book, From Poverty to Progress, those regions repeatedly transformed their agricultural systems by innovating new technologies, skills, processes, and institutions. The achievements laid the foundations for the growth of Commercial societies in Northern Italy, Flanders, Netherlands, and Southeast England. The result was the first widely-shared progress on planet Earth.

Later agricultural transformations in Commercial societies laid a strong foundation for the Industrial Revolution in Britain. The Industrial Revolution included the invention of agricultural, food processing, food storage, and transportation technologies that spread those benefits even wider. Agricultural productivity accelerated rapidly in Britain, Northwest Europe, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. In particular, the United States was able to turn the prairies of the Midwest into massive export industries that enabled other nations to specialize in crops other than grain. While it took centuries for the benefits to spread beyond a few regions, today we have an astoundingly productive world agricultural system.

The Green Revolution

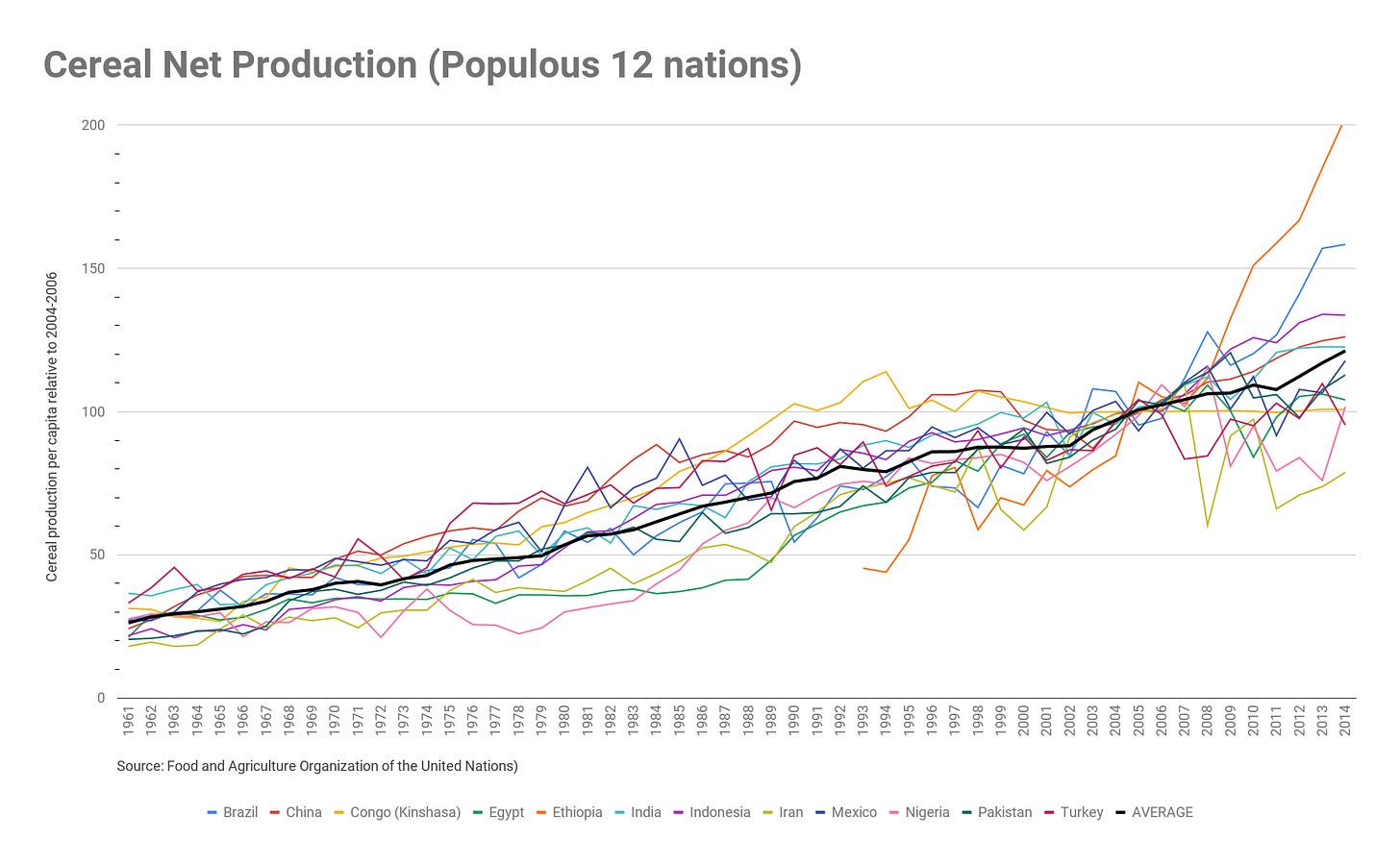

The Green Revolution of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s accelerated the trend even further and spread the benefits to Latin America and Asia. The Green Revolution consisted of new agricultural technologies such as:

bioengineering of high-yield varieties of cereals

chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and

These technologies enabled much greater mechanization of agriculture in Asia, which enabled peasants to generate a food surplus that enabled their children to migrate to cities and get jobs in emerging manufacturing industries.

The Green Revolution laid the foundation for the industrialization of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, India, and parts of Southeast Asia. The Green Revolution had a mixed impact on Latin America because that region was unable to develop competitive export industries (the Fourth Key to Progress).

Global Food Distribution System

Today’s modern food surpluses are based on the following:

1. The application of modern agricultural technology, most of which is based upon fossil fuels, fossil fuel byproducts, and genetic research.

2. Regional specialization in food production

3. The global trade system.

The combination of these three factors has effectively overcome the greatest constraint to progress in virtually every society in history: geographical constraints on food production and distribution. All of these factors were created by Western nations that first experienced progress, particularly the United States. Developing nations enjoy the benefits of that progress to the extent that they can copy modern agricultural technologies.

The Limits of the Green Revolution

Unfortunately, the Green Revolution had relatively little impact on Sub-Saharan Africa. This is the primary reason why that region has experienced the least progress over the last century. A key factor is that agricultural innovation is heavily constrained by local geography.

Africa’s geography is particularly challenging. Africa consists mainly of Desert, Tropical Forests, and Tropical Grasslands (or Savanna). The non-Forest ecoregions in Africa experience extremes in precipitation. Rain is almost entirely concentrated in the rainy season, while the dry season is close to Desert conditions. Many regions also have relatively unproductive soil.

Previous agricultural researchers deliberately targeted Asia and Latin America because the regions had geography better suited for plow-based cereal agriculture. Africa’s agricultural system, which was largely based on hand-tilled root vegetables presented different and in some ways more difficult challenges.

In addition to geographical differences between Sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world, the region also suffers from great geographical variability within the region. Geographical heterogeneity is far greater in Sub-Saharan Africa than in any other region in the world. Among the differences are soil, acidity, moisture, and temperature, all of which are critical to agriculture. There are even substantial differences in these characteristics within small plots of land. These geographical variations mean that one big solution or set of solutions (i.e. the Green Revolution) does not work for the entire continent (Suri and Udry).

Opposition to Green Revolution

Another reason that the Green Revolution failed to impact Sub-Saharan Africa was due to intense opposition from Green activists. Ironically, the Greens strongly opposed, and still oppose the Green Revolution.

Today political activists, NGOs, and multilateral aid institutions attack the foundations of agricultural productivity in the name of “sustainability.” Research and use of fertilizers, genetically modified organisms, pesticides, irrigation, and other agricultural technologies have been brought to an almost complete halt in the poorest countries. Nor do wealthy nations do much to take up the slack.

Greens have demonized wide swaths of agricultural research that are desperately needed by developing nations and can create better products in rich nations. Some have even stooped to physically destroying experiments to create new crops, such as Golden rice, that can save millions of children from malnutrition and death. Governments are afraid to fund many studies in the field for fear of backlash from the Greens.

The major successes of the Green Revolution in Asia and Latin America occurred in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s before the Green movement became politically influential among international NGOs. For this reason, Greens failed to stop the Green Revolution in Asia and Latin America in the earlier phase, but they succeeded in doing so in the later phases of the revolution.

Agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa (except for South Africa) since 1960 has lagged far behind trends in the rest of the world. These yield gaps are largely due to differing levels of technologies. In particular, the usage of fertilizer and irrigation in Sub-Saharan Africa lags far behind the rest of the world (Suri and Udry).

Some researchers have claimed that impoverished African farmers do not have the capital to invest in the latest technology, but limits in their ability to finance investments using credit explain only a small part of the problem. Nor is the problem with crop insurance or a lack of information (Suri and Udry).

A Second Green Revolution

We need a Second Green Revolution that dramatically increases agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa and other poor developing nations. A Second Green Revolution would enable local farmers to grow more crops, enabling rural people to migrate to more productive cities and increase the amount of wild habitat by reducing farm acreage.

Public agricultural universities played a key role in making American agriculture the most productive in the world. In addition, that funding played a key role in promoting the Green Revolution that drastically increased agricultural productivity in Latin America and Asia.

Without these critical increases in agricultural productivity, most developing nations would still be rural, as their people would have had to remain dispersed to grow crops. Just as increased agricultural productivity promoted the growth of Commercial societies in Europe and their later industrialization, so did it promote today’s transformational economic growth in Asia.

In a previous article, I argued that innovation prizes are the most cost-effective means to trigger breakthrough innovation. Obviously, governments in Sub-Saharan Africa do not have the financial resources to sponsor innovation prizes. But governments in wealthy nations and NGOs that raise money from the same nations do have the financial resources.

We should create innovation prizes that enable developing nations, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, to radically increase the productivity of local agriculture. This will not only greatly increase the standard of living in those regions, but also reduce the human footprint on natural habitats. Low-productivity agriculture promotes poverty and habitat degradation, while high-productivity agriculture promotes wealth and reduces farm acreage.

A Second Green Revolution targeting Sub-Saharan Africa, preferably funded via prizes, could have a profound positive effect on the region. Latin America, Asia, and wealthy nations in North America and Europe would also benefit. Given the current political climate, the United States seems to be the only country with the potential to initiate another Green Revolution, and they have not done so yet because of ideology.

Agricultural research funded by the American government and American corporations was critical to making progress on farm productivity. American agricultural universities and the US Department of Agriculture have played a leading role in this for well over a century. We need more of this, not less. It is probably the single most effective way to expand wild habitat, so it is disturbing that environmentalists are so strongly against it.

Admittedly the intense geographical variations within Sub-Saharan Africa will make it difficult to design effective innovation prizes. We will most likely need an entire constellation of innovation prizes that focus on specific crops and specific sub-regions within the continent.

The best solution is not clear to me at this point, but I have confidence that if Western governments, agricultural corporations, and agricultural research stations come together with local African agricultural research stations and farmers, they can come up with effective prize designs that can enable a few carefully chosen pilot projects. If those first innovation prizes yield results, then the concept can be expanded to many more innovation prizes that span the continent.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my second book Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can read other articles on developing nations, including:

Why developing nations are still poor:

What wealthy nations can do to help developing nations:

What developing nations can do to help themselves:

I think you overestimate the influence of green activists in African policy making. Your model of the world assumes Africans have no agency over their own lives. It's not like these green activists managed to stop Asian manufacturing powers from being more accepting of carbon emissions and environmental degradation. It's ultimately up to Africans to sort out their agricultural problem by themselves. They can't wait around for foreigners to solve all their problems. Imo their system of communal land ownership is the primary reason behind weak land productivity. Ethiopia and Rwanda managed to break free from this system and have managed to make impressive gains.

> While getting enough food to survive is easy in modern societies, it was an epic task for our ancestors. For the overwhelming majority of our ancestors, the quest to acquire enough food to survive took up the majority of their waking hours. It was an obsession, and all of society was organized around the most effective means to do so within the local environment.

This wasn't the problem in most of Africa or the tropics generally. There acquiring enough food was so easy that there wasn't much need to innovate, meanwhile population density was kept in check by tropical diseases and megafauna that had co-evolved with humans.