Invasion Antwerp 1944

What the Allies should have done instead of invading Normandy in June 1944

This Substack column is primarily about human material progress. Occasionally, though, I like to jut off into other subjects that interest me.

In addition to being interested in political, economic, and technological history, I am also very interested in military history. Military history is very relevant to overall history because large nations with powerful militaries often have a huge effect on how other nations develop. The outcome of wars bends history in a certain direction depending upon which side wins. And who wins in wars is one of the great contingencies (i.e. has a large amount of randomness) in human history.

Today I will write about World War II, whose outcome created a breakthrough that helped to spread human material progress.

Read the other articles in my series on Invasion Antwerp 1944 (an alternate military history):

Invasion Antwerp 1944 (this article)

How would the German army respond? (upcoming)

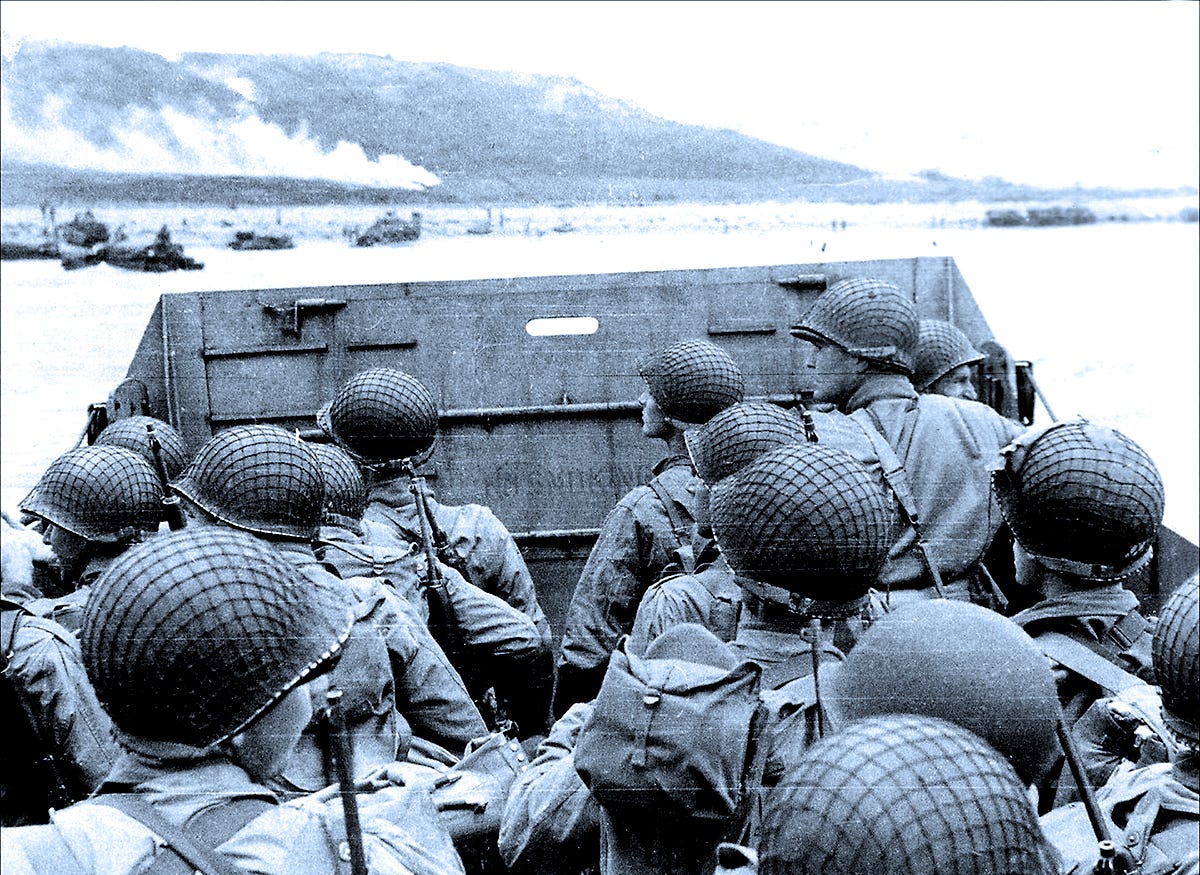

The Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 (popularly known as “D-day”) was one of the most important events in the 20th Century. It was also one of the largest amphibious assaults in world history and opened up an entirely new front in the largest war in the 20th Century.

And D-day’s success was far from certain. If the amphibious assaults on June 6 failed to achieve a sizeable beachhead (which nearly happened at Omaha beach), then the Allies might not have been able to open the Western Front in 1944 at all. This would likely have changed the map of post-World War II Europe by pushing the Iron Curtain further West.

D-day was a heroic effort, but what if I told you that the entire effort may have been a mistake? (Or more accurately, it was not the optimal strategy).

What if I told you that there was another option that was apparently overlooked by Allied generals and planners?

What if I told you that another location might have allowed the Western Allies to cross the Rhine in force in 1944 instead of March 1945 (as they actually did).

What if I told you that Allied generals fundamentally missed the most important factor for achieving victory on the Western front?

The big picture

This was the situation in the first half of 1944. The Western Allies had massive numerical superiority, particularly in weapons platforms, but they had a very hard time:

Transporting them to France, the Low Countries and Germany

Keeping them in supply enough for a general offensive (i.e. all divisions attacking at once)

In other words, they had a huge global advantage in military power, but geography made it difficult to apply that power to Northwest Europe, except in the air.

The Allies tried numerous methods to get around this fundamental problem including:

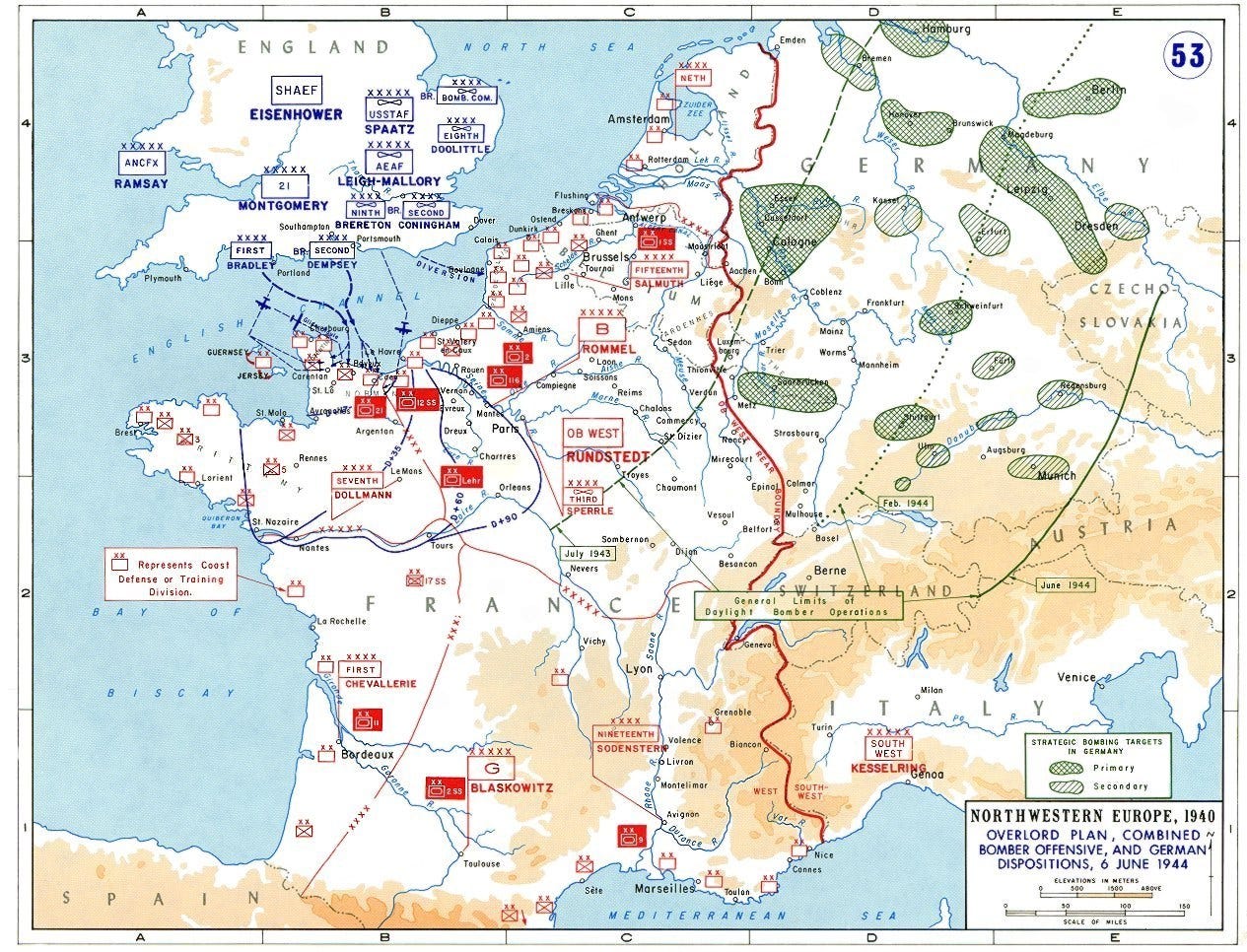

Massive bomber campaign starting in June 1943.

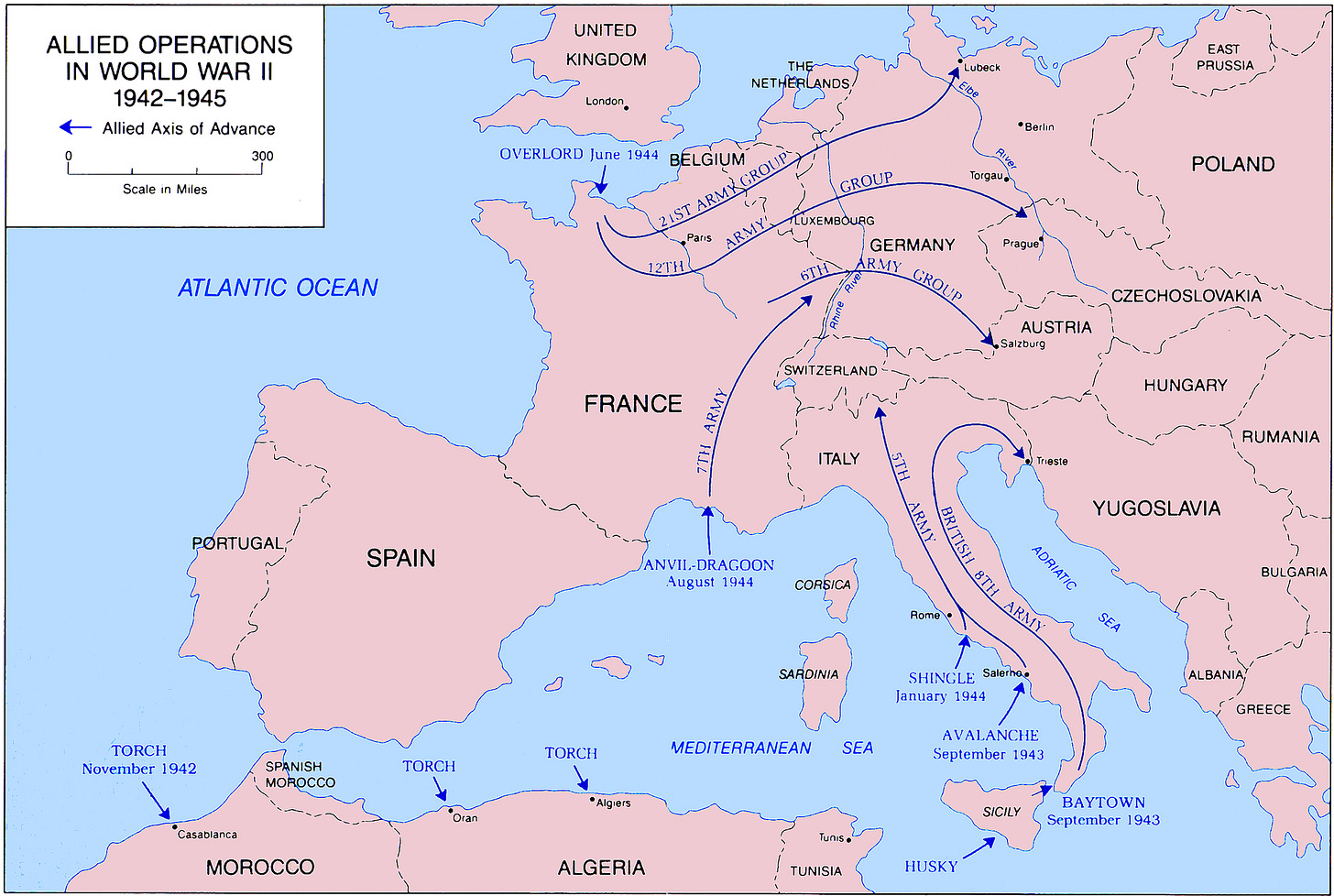

Opening up a second front in North Africa with Operation Torch in November 1942

Assaulting Sicily in July 1943

Assaulting mainland Italy in September 1943

After the invasion of Normandy, the Allies assaulted Southern France with Operation Dragoon in August 1944.

Discussions of invading Northwest Europe in 1943 (but these were shelved)

Some discussion of invading the Balkans (but these were shelved)

All of those implemented military operations contributed to the defeat of Nazi Germany, but none were decisive. Everyone knew that opening a “second front” in Northwest Europe was the only means to achieve a decisive victory. And Stalin put enormous diplomatic pressure on the Western Allies to do it as soon as possible.

What did the Allied general focus on?

If you look at the historical record, Allied generals typically believed that the key factors necessary for achieving victory on the Western front were (in order of chronology):

Breaching the Atlantic wall (i.e. the initial amphibious assault).

This actually happened on June 6, 1944, although Allied forces were mired in the Normandy hedgerows until Operation Cobra at the end of July 1944. This led to a sudden Allied breakout that collapsed the German front lines in August 1944.Breaching the Siegfried Line or West Wall (the defensive fortifications along the western pre-war German border)

This actually happened in Operation Veritable from February 8 to March 21, 1945, although the Allies reached it in places in September 1944 and fought there through the fall and winter.Breaching the Rhine river.

This actually happened in Operations Plunder and Varsity in late March 1945.Cutting off the Ruhr region (the industrial heartland of Germany) from the rest of Germany. It was hoped that this would cause a quick German surrender.

The Ruhr region was actually cut off in April 1945.

All of those factors were extremely important, but they missed what should have been the single most important factor in their pre-invasion planning: Antwerp.

As partial evidence of my claim, notice the long time delay between the Allied breakout from Normandy in late July 1944 and the final breaching of the Rhine in late March 1945 (about seven months). This was largely, though not entirely, due to logistics. And only Antwerp could solve that logistics problem.

Think Logistics first, then strategy

This is a very common problem among generals, military historians, and military history enthusiasts. They love to think and talk about strategy, tactics, and weapons. Logistics often gets forgotten until something goes wrong, which it did on the Western Front from Aug 1944 to Feb 1945.

The Allied generals were well aware of the importance of ports in general. Their Overlord plan was to:

Construct:

temporary Mulberry harbors at Omaha and Gold beaches to provide a temporary port until Cherbourg was seized. Unfortunately, one of the two mulberries was destroyed in a huge storm on June 19, 1944.

underwater pipeline to move petrol, oil, and lubricants under the Channel.

Seize the port of Cherbourg, the largest port in Normandy, as soon as possible.

And then follow up quickly with the seizure of all the other ports in Normandy and Brittany.

Local logistics personnel partially made up for the lack of ports with the innovative idea of landing Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) directly on the beach at scale. This was very successful and innovative, but it did not make up for a lack of ports.

Logisticians also wanted generals to construct an artificial port in Quiberon Bay (but it never happened).

The critical missing factor: supply

I contend that any major ground combat in Belgium, the Netherlands, and around the Ruhr necessitated a fully built-up military supply chain around one big port. By “fully built-up supply chain” I mean:

A port with plenty of storage facilities with:

Peace-time capacity that was far above military needs (peace-time shipping also needed to keep flowing)

Wide enough and deep enough so that Liberty ships from the USA could directly off-load at quays and piers.

Plenty of:

quays and piers

hydraulic and electric cranes

loading bridges

grain elevators

warehouses

cold-storage chambers for fresh food

petroleum storage tanks

Direct access to rail lines, canals, rivers, and highways

Very large and well-organized supply depots far enough away from the port so the port facilities are not blocked by stored materials.

Very secure high-capacity transportation lines:

between the port and the supply depots (ideally via rail or canal)

between the supply depots and the front-line units (ideally with trucks)

And those supply lines had to be flexible enough to keep up with fast-moving armored breakthroughs which can happen with little notice. Only trucks could perform that role.

Only three or four ports could possibly fit all or most of those criteria:

Antwerp

Rotterdam

Hamburg

Bremerhaven (and this port might not be big enough)

The critical flaw in the invasion of France

What many do not understand is that even a large number of smaller ports and beaches could not have substituted for those four ports as the hub for the Allied supply chain. For reasons of history, economics, and geography, French ports were far smaller than ports in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and the UK. By far the biggest French port was in Marseilles, which was very far from Germany.

Trying to land in Northern France (regardless of which part of Northern France) would be like asking a large person to crawl through a narrow pipe. It simply does not matter how many narrow pipes you have; the problem still remains the same.

Sure, given enough time, the Allies could have innovated, but once the German front lines collapsed in late July 1944, time was something that the Allies did not have. Allied ground units had to pursue the retreating Germans, but because of the fundamental supply problem, they could not pursue with enough units to keep the Germans on the run.

The result was that the Germans finally regrouped just in front of the German border in September 1944. By then the under-supplied Allied units had lost their advantage. That is why the front lines barely moved between September 1944 to February 1945 (five months), except:

Operation Market Garden, which was primarily supplied via air.

Alsace-Lorraine, which was primarily supplied from the port of Marseilles.

Key decisions

The key decisions for D-day (the Allied code name for the invasion date) was:

When?

Where?

When?

When was the first that needed to be answered. Stalin’s answer was “Now, if not sooner.” The Americans said Summer of 1943. Churchill and the Brits said some version of “Hold up, Bro. The Germans are going to kick your ass if you land inexperienced American divisions in 1943. Let’s go for something easier first.”

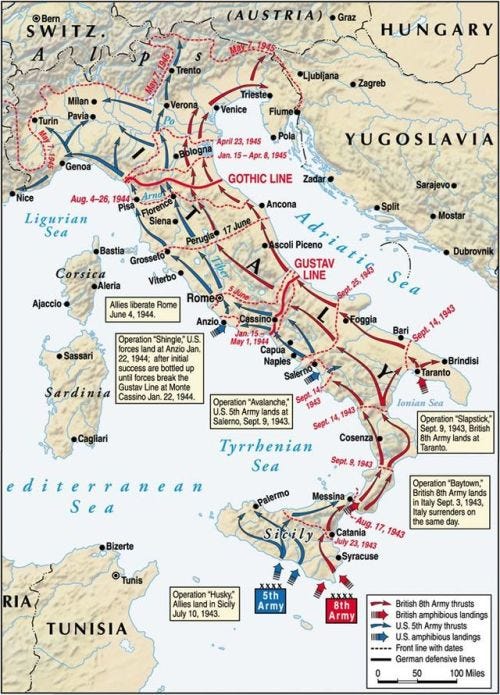

The North African campaign of 1942 and the Italian campaign of 1943 were largely an attempt to go after a much easier target (Italy plus a relatively small German force) to gain experience and knock Italy out of the war. This largely worked, but the Italian front stalled in October 1943 about mid-way up the Italian peninsula. As late as April 30, 1945, the Allies still had not breached the Alps. This was only a little over a week before the Germans surrendered.

Give the geography, the Italian campaign was always doomed to remain a side-show. The fundamental problem was that the Italian peninsula was so mountainous and narrow that a relatively small number of German divisions could hold off a much larger Allied force from moving northward.

Since it was not possible to support the logistics of major offensives in both Italy and Northern France simultaneously in 1943, this pushed the date back to 1944. Climate and weather pushed the date back to the summer of 1944. Original planners chose May 1944, but delays in receiving supplies and combat units in the UK pushed the date back to June 5, 1944 (the earliest possible date when tides were favorable).

Where?

Once June 1944 was chosen as the date, the next big decision was where. I am amazed at how little systematic study of this problem exists in books and online resources. Typically, the topic of beach selection is skimmed over with a discussion of Pas de Calais, France compared to Normandy. Some studies also include possible landing sites in St Malo or Brittany.

To the best of my knowledge, there is nothing in the historical record about a systematic attempt to explore the possibility of assaulting southern Netherlands and Antwerp. I am not saying that it did not happen. I am saying there is nothing that I can find in the historical record.

If I am wrong, please give me a reference in the Comments. And I don’t mean a chapter in a book. I mean something on the scope of this official US Army record of the logistics of the Western Front (which every WW2 buff should read):

https://history.army.mil/html/books/007/7-2-1/index.html

https://history.army.mil/html/books/007/7-3-1/index.html

While very dull to read, those two books are a very comprehensive overview of the logistics planning and execution before, during, and after D-day. In total, the two volumes are 1200 pages long!

That is what I mean by systematic.

And, by the way, it was reading those two books that made me realize just how important Antwerp was. It gave me the initial idea that Antwerp might have been a better location for Overlord in June 1944 than Normandy.

At first, I thought I must have been missing something. Maybe there was a big reason why Antwerp was worse than Normandy. Was it German ground forces? Coastal artillery? Tides? Weather? Beaches? Distance from England? The possibility of the Germans flooding the area by breaking the dykes? Was there something missing from the port of Antwerp?

One by one, I found evidence that by virtually all these criteria, Antwerp was better or equal to Normandy. The more research that I did, the more I began to think that no one in the Allied upper command had seriously thought about the option (or at least it is nowhere documented in the historical record).

For a long time, I seriously thought about writing a book about the subject, but I decided to focus on progress first. But I recently started to write my thoughts and research findings in this Substack column.

Possible locations

Let me be clear, Normandy was clearly superior to all other landing sites that I mentioned above. Let me quickly go through the reasons why here:

The Pas de Calais region was the closest to England, but it was very heavily fortified. Hitler and the German generals were confident that this was the Allied plan. Allied disinformation only increased their false confidence (Rommel was the most important general who thought it would be Normandy).

Pas de Calais was later taken by land in Operation Undergo in September 1944.Every landing site west or south of Normandy was much too far from the Ruhr and all the potential ports were too small (by far).

Southern France had the largest port in France, Marseilles, but it was much too far South. It was at best a suitable logistics base for clearing the Rhone river valley and getting up to the Rhine in the Alsace-Lorraine area. It was much too far south to influence combat operations north of Luxembourg.

Southern France was later taken by amphibious assault in Operation Dragoon in August 1944.Netherlands (at least most of it) had a huge port (Rotterdam), but it was easily flooded by Germans destroying the dikes and then building a new defensive line between the Rhine and the Ijsseelmer.

Most of the Netherlands was not cleared until April 1945.Norway was not connected to the European mainland. Norway was not liberated until after the war.

Denmark was easily isolated by German troops at the bottom of Jutland. Denmark was not liberated until after the war.

A direct assault on the German North Sea coastline was well-defended by naval forces and pre-war fortifications. Hamburg and Bremen were the only ports other than Antwerp and Rotterdam capable of supplying the Western front.

The choice of Normandy seemed obvious, but was it?

A better option?

In my next posts in this series, I argue that the proper location for the combined Allied amphibious and airborne assault on June 1944 was:

Port of Antwerp

One reason why the Allied generals may not have initially liked Antwerp as a target for D-day was that it was not actually an ocean port. It is an inland port about 50 miles up the tidal estuary at the mouth of the Scheldt river.

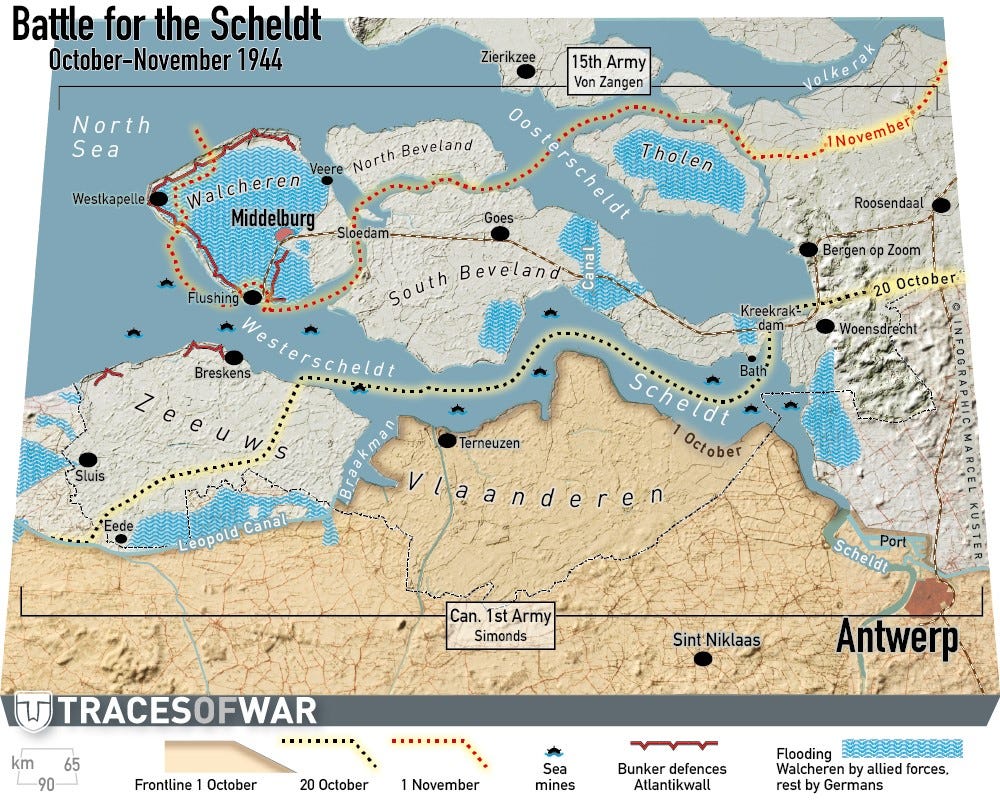

The south bank is Zeeland (on the mainland) and the north shore is South Beveland island. Finally, the mouth of the estuary is guarded by Walcheren island. This means that capturing Antwerp was not enough. You also had to clear both banks of the Scheldt river.

Below is a map of the region covering the period when the Scheldt was actually cleared in Oct-Nov 1944. The flooded regions were not flooded in June 1944.City of Antwerp.

The Allies actually captured Antwerp without a fight on September 4, 1944. Unfortunately, Allies forces did not clear the following key areas. They instead hastily initiated Operation Market Garden.The Zeeland coastline in southern Netherlands.

The Allies did not sweep the area until the Battle of the Schedlt in Oct/Nov 1944.Walcheren island (which blocked the entrance into the port of Antwerp). The Allies did not sweep the area until the subsequent Operation Infatuate in early November 1944.

Antwerp Airport - this was the least important of all these targets, but it would have enabled the Allies to fly in Air Assault divisions and supplies against an inevitable German counter-attack.

This assault should have been instead of Normandy, not in addition to Normandy because logistics would not allow for accomplishing both.

So you think that Allied generals were stupid, right?

No, I do not think that the Allied generals were stupid.

Allied generals were generally competent enough to do their jobs, and the least competent tended to be relieved of command. I believe that Allied generals did not have a full understanding of logistics and its impact on strategy and maneuver.

If they did, someone would have said “Hey, what about Antwerp? It is the biggest port in Europe, and it is much closer to the Ruhr than Normandy.”

Generals have to make quick decisions with limited information, while their enemy is trying to do so faster. War is always a series of sub-optimal decisions made under intense stress. The side that makes the fewest tends to win.

And strongly disagreeing with your commander risks a court martial, so being a “voice of reason” had its limitations on your career.

But now we can do better.

To learn from history, we need to think through those decisions so that future generations will make better decisions in the future. So let’s try it on D-day…

Read the other articles in my series on Invasion Antwerp 1944 (an alternate military history):

Invasion Antwerp 1944 (this article)

How would the German army respond? (upcoming)

I know military history buff can get really excited when discussing “What Ifs” so please let’s keep to the topic of assaulting Antwerp in 1944. I do not want a general discussion of Allied mistakes on the Western Front or who was to blame.

As usual, the Commenting rules are:

Read the entire post first.

Given that my opinions are unorthodox, do not assume that you understand my point of view from the headlines or skimming the article.Stay on topic. Keep the focus on Antwerp 1944.

Be respectful and open to learning. I will do the same.

![[Map] Map depicting the Allied campaign toward Germany, 26 Aug-14 Sep ... [Map] Map depicting the Allied campaign toward Germany, 26 Aug-14 Sep ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!g2iK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc124830a-5896-44bb-ab80-319bebd7c9d8_1265x965.jpeg)

It seems to me that the main difficulty with the invasion starting in Belgium is that the Allies would be surrounded in all sides and vulnerable to being trapped in a relatively small beachhead. Now, of course, that's what happened in Normandy, at least for a few weeks, but once they broke out, the German forces in Western France were forced to retreat Eastward or risk being cutoff and forced to surrender. But in Belgium, that wouldn't have been the case - the Germans would have had much more room for a tactical retreat and counterattack, and wouldn't have had to abandon France (at least not as quickly). Whether that outweighs all of the advantages of Antwerp, I don't know.

This is interesting. Because the war ended victoriously in less than a year, it's a decision that we seldom see second-guessed.

It's the sort of thing I wish I could bounce off my late father, who obsessively studied World War 2 (as a hobby), and D-Day in particular, much more deeply than I ever have, including obsessively studying primary sources and orders of battle. He loved to discuss it with me growing up.

Two points I didn't see you call out that would seem to be in favor of the idea that Normandy was a mistake:

1. Allied intelligence or planning supposedly screwed up on accounting for the bocage and underestimated the hindrance that it would prove.

2. The Allies vastly overestimated the value of taking nearby Brittany. It turned out to not even be worth the trouble.

As for "Why not Antwerp?", I can only speculate one potentially rational reason that I didn't notice you otherwise calling out: Was there a concern that concentrating forces along the English coast (including air support) for an eastward offensive through the North Sea would have been detected by German intel, which could have concluded that Antwerp was the only viable target for such an operation and therefore heavily reinforced it? The Channel coast seems to offer a wide range of possible landing sites, and with forces prepared for a cross-Channel invasion, I imagine it was easier for the Allies to pivot to another Channel option in response to the German disposition if, for example, it was noticed that the bluff at Calais had failed and the Germans were heavily reinforcing Normandy.

I can also speculate an irrational reason: I've never heard this mentioned, but was politics at play? Did De Gaulle (or other influential Frenchmen) play a role in prioritizing the liberation of France and, symbolically, making a return to the continent on French soil? Did Churchill or Roosevelt believe that France was owed the swiftest possible liberation? Was there an expectation that a swiftly-rearmed France would play a larger role in the last stage of the war than it actually did? Or perhaps, was the existence of the Free French forces anticipated to secure more useful collaboration from the French Resistance and from liberated locals than would be the case in Belgium?