Social Mobility vs. Upward Mobility

And why Upward Mobility is far more important

My From Poverty to Progress book series and this Substack focus on the concept of material progress, which I define as “the sustained improvement in the material standard of living of a large group of people over a long period of time.” Though I believe that material progress for entire societies is extremely important, we can also not lose sight of the fact that some people within those prosperous societies do not fully experience the benefits of that progress.

My third book the From Poverty to Progress book series is organized around the concept of Upward Mobility. This concept is about ensuring that the maximum number of people in those societies experience the benefits of material progress.

When I first mention the concept of Upward Mobility, many people confuse it with the concept of Social Mobility. The two concepts are related to each other, but they are not the same. In this article, I will explain the difference between Social Mobility and Upward Mobility, and why I believe the latter is far more important.

The short version is that:

Social Mobility is zero-sum because it focuses on relative position within a society, while

Upward Mobility is positive-sum because it focuses on the absolute levels of material standard of living.

Let me explain why.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

Why Progress and Upward Mobility should be the goal, not Equality

The Pathway to Success (first of three articles in series)

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

What is Upward Mobility?

Upward Mobility is the increased material standard of living that a person experiences throughout their adult working lives. This increased material standard of living for an individual is caused by a combination of:

Long-term economic growth for the society that they live within (i.e. material progress). Without this, all the other factors are unlikely to lead to an increased material standard of living.

The talent of the person, which

largely reflects genetics, but also

family upbringing, and

quality of schooling

Critical Life Choices that a young person makes, including:

Education

Job Skills

Criminality and violence

Sexual activity and contraception

Relocation to regions with greater economic opportunities

Occupation and work effort in the occupation

Marriage

Having children and parenting

Long-term work effort. Making wise Life Choices puts an adult on the best possible life trajectory, but they still have to keep working for decades to experience a constantly increased material standard of living

Just plain random luck (both good and bad).

Notice that an individual has very little choice over the first two factors and the last, but an individual has much more control over Life Choices and work effort. So Upward Mobility is both about societal factors as well as individual choice.

Notice also that nothing about Upward Mobility is zero-sum. None of the above factors hurt anyone else’s chances of experiencing Upward Mobility. A large number of people making wise Life Choices and working hard for decades actually:

increases material progress for everyone else in society and

increases their chances of being able to experience Upward Mobility.

Win-win.

What is Social Mobility?

Social Mobility is about an individual’s relative position within a society.

Typically, those who embrace Social Mobility as a goal uphold the idea that individuals should be able to move up and down within society based on their own talents and efforts, regardless of:

class, caste, or order

political or family connections

title.

When compared to pre-modern societies where people were born into a certain social class or order, Social Mobility is highly desirable. Social Mobility implies that people are being judged on Merit rather than Privilege. To that extent, Social Mobility is something that we should all believe in.

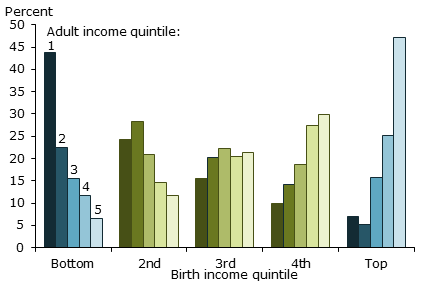

Typically, when social science researchers study Social Mobility, they array each individual based on a specific metric of socioeconomic status such as:

income (the most common metric)

wealth

education, or

social status.

For simplicity, Social Mobility researchers typically categorize individuals into quintiles (for example: Top 20%, Bottom 20%, and the three other quintiles).

One point that most people neglect is that Social Mobility is inherently zero-sum. A person cannot move up to the 60th percentile or the top quintile unless another person moves down from that rank. So while we tend to focus on the ability of individuals to move up, we also need to be cognizant that there are an equal number of people moving down.

Typically, people who focus on Social Mobility ignore that fact. They focus on the probability of poor youths moving up into a higher social rank, but they neglect the associated drop by wealthy youths dropping ranks. The ability of poor youths to move up in society based on their talents is clearly desirable, but the necessary drop for wealthier people is less so.

An even more serious problem with Social Mobility is that the concept completely neglects the changes across all of society, particularly long-term economic growth. If for example, a society is experiencing strong long-term economic growth, a person may drop in rank but still achieve a higher material standard of living. And when a society is experiencing a long-term downturn in economic growth, even the most successful may be worse off materially.

By holding change across society constant, the concept of Social Mobility effectively controls for material progress (i.e. long-term economic growth experienced by the entire society). The single most important determinant of the material standard of living of an individual is the average material standard of living of the society that they live in. So while it might be useful to control for economic growth in some cases, we need to focus on concepts that include long-term economic growth. Otherwise, we reconceptualize a positive-sum world where we can all benefit from economic growth into a zero-sum world where everyone is competing for social status.

What about genes?

Another major problem of Social Mobility research is that researchers implicitly assume that all humans are equal, so any differences in outcome are caused by society. This is a very common assumption for those with Left-of-Center politics, of which the vast majority of social scientists are.

More specifically, high social mobility typically is thought to mean that the institutions in society make decisions based on merit. Low social mobility is thought to mean that societal institutions make decisions based on privilege, personal connection, and corruption.

As is common in most social sciences, researchers do not even consider biology. Instead of talent being randomly distributed throughout the population, it is far more likely that a significant portion of the variation in talent is caused by genetics.

This is very much in alignment with genetic research, which typically concludes that genes capture 40-60% of the variation of any given characteristic, behavior, or outcome. This is true for obvious things such as height, skin color, eye color, and other physical characteristics, but it is also true for very complex societal outcomes, such as level of education or income.

For an excellent overview of the current state of research on the link between individual outcomes and genetics, I would recommend reading Human Diversity: the Biology of Gender, Race, and Class by Charles Murray.

Let me give you an idea of how important explaining 40-60% of the variation with one variable is. Today, when a social scientist does a sophisticated statistical analysis that shows that their favorite theory explains 5% of the variation after controlling for other variables, they are ecstatic. In the field of social science, explaining 5% of the variation is considered very powerful evidence. And to propose a statistical model where all variables account for 40-60% of the variation is considered very respectable.

But here we are talking about 40-60% of the explanation explained by one variable! That is extremely rare in social science. And it is even more rare for social scientists to completely ignore such a strong causal variable. This can only be explained by ideological self-censorship where social scientists refuse to accept the importance of biology on human outcomes.

Genetics explains such a huge amount of the variation across so many different human characteristics and behaviors, that it must be a starting point for every social science theory. But it almost never is. And genes must be a controlling variable in every statistical analysis. But it almost never is.

So what accounts for the other 40-60% of variation in outcome? Well, now we are in the domain of social science with all its competing theories. Very few of those theories can come up with definitive evidence proving their theories, and we are left with constant arguments between experts in their field.

I believe that a key reason that social science has had problems creating consensus around theories is that social scientists refuse to acknowledge the key causal variable in most domains of human behaviors and outcomes: genetics. Refusing to accept the role of genes undermines our understanding of everything else.

All the non-genetic 40-60% of the variation in outcome is largely unknown, and it is unknown exactly because the vast majority of social scientists refuse to acknowledge the role of genes so they do not control for its influence. This is a fundamental mental block that social science must overcome.

Meritocracies sort for genes

So let’s get back to our discussion of Social Mobility. Let’s just start with the assumption that 40-60% of the variation of talent is caused by genes and remain agnostic about all other causes. In a perfect Meritocracy, those with “talented” genes (whatever those are) will filter to the top with each generation, while those with “less talented” genes will filter to the bottom.

If you keep that filtering process going for many generations, then you have a society that appears to have low levels of Social Mobility. The social scientists then conclude that something is wrong with that society, likely some form of privilege, personal connection, and corruption.

If you add on the reasonable assumption that “talented” men will prefer to marry and have children with “talented’ women, and vice versa, then Meritocracy creates even lower levels of Social Mobility with each generation. Now we have both institutions and mating preferences sorting for “talented” genes.

So low levels of Social Mobility might be caused by either:

Societies with a rigid system of classes, orders, or castes, or

Societies with very high levels of merit-based decision-making by its institutions

Ironically, these very different types of societies lead to exactly the same levels of Social Mobility.

Traditional regimes had low Social Mobility

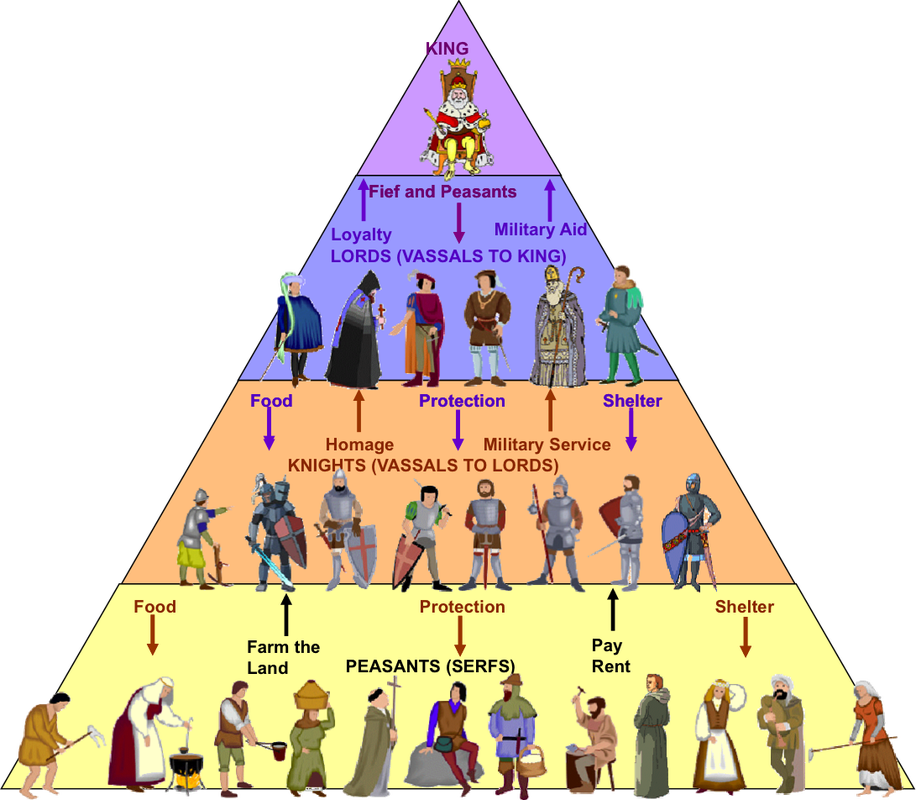

Virtually every nation that currently has high levels of per capita GDP went through thousands of years of being Agrarian societies (i.e. agricultural societies with animal-driven plows). Agrarian societies had an extraordinary level of social stratification.

Each Agrarian society had a highly developed system of classes, orders, or castes. Each group separated people based on how they earned a living. Peasants were invariably at or near the bottom. The king or emperor was invariably at the top of the social order. Beneath him were royal bureaucrats, titled nobility, landowners, religious leaders, and military officers. Merchants and artisans were invariably near the bottom, sometimes even below the peasantry, for example in China.

Elites in Agrarian societies were obsessed with status. Each class was denoted by its unique way of dressing, mannerisms, hairstyles, spoken accent, architecture, and more. All of this communicated the message that the membership of each class was closed, immortal, and not subject to questioning. Many Agrarian societies closely tied these classes to religious beliefs that gave the hierarchy even greater legitimacy.

Even the most talented had great difficulty moving up out of their order, and even small amounts of social mobility were achieved via patronage (support from your superiors). So in virtually all Agrarian societies, social mobility was very low. The class one was born into was very likely to be the class that one died within.

Transitioning to Meritocracy increases Social Mobility

One of the great achievements of Commercial societies (such as the Medieval city/states of Northern Italy or the Dutch Republic) was to tear down many of these class barriers to make political, military, economic, and religious organizations more merit-based. This unleashed a great deal of talented merchants, farmers, soldiers, and artisans to move up into positions of power within institutions. The effects of the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution spread meritocratic principles even further throughout the world.

All of the above undoubtedly increased the levels of Social Mobility. People did not realize it at the time, but new meritocratic institutions were sorting people by their genes.

But then Meritocracy lessens Social Mobility

At some point, however, Social Mobility starts moving in the opposite direction. Not because society is becoming less Meritocratic, but because they have been relatively Meritocratic for many generations. With each generation there are fewer genes to sort, so most people are already born into their appropriate status slot. Mismatches decline with every generation.

Some people use exactly this argument to explain why Meritocracy is bad. Some of those writers claim that nepotism and credentialism are inherent to Meritocracy, but both problems go back millennia to Agrarian societies. Rich and powerful families always try to cheat the system for the advantage of their children.

The rich and powerful are always looking for markers that separate them from the masses. They signal their status with dress, mannerisms, hairstyles, spoken accents, rituals, and more. And those signaling strategies are carefully crafted to make it difficult for the masses to copy them.

Credentialism is just the latest strategy.

More importantly, nepotism and credentialism are both deviations from Meritocracy that undermine Meritocracy. In the linked article, I present alternatives to nepotism and credentialism that expand Meritocracy.

The problem is that opponents of Meritocracy neglect the single most important factor in Upward Mobility: living in a society that is experiencing long-term economic growth. Organizations need to be able to hire and promote those with the skills to use technology and work well with others. Without this, they lose their ability to compete with other organizations for limited resources. And for the society overall, this means less material progress.

We should leverage genetic inequality, not ignore it

Meritocracy leverages genetic inequality for the benefit of society by placing those persons who are best able to make contributions to society in the best place to do so. This benefits those with talent and the rest of society. For this reason, any movement away from meritocracy will be a movement away from material progress. This will hurt the poor and the working class in the long run, even if it appears to help them in the short run.

Regarding genetic inequality, the Left typically takes one of two strategies:

Ignore genetic inequality and shame anyone who raises the issue.

Try to tear down the successful who benefited from their genes in the name of helping the poor, working class, and racial minorities.

Both strategies do great harm to society.

Those on the Left see genetic inequality and deem it unfair because it leads to inequality of outcome. But this inherent genetic inequality should be used to the advantage of society, not ignored or complained about. And people who correctly point out genetic differences between people should not be shamed for being honest.

What the Left misses is that society needs to put those with talent (regardless of how they got that talent) in a position where they can make the maximum contributions to society in their career. If this is done at scale this is an important factor in generating progress that all of society enjoys.

Meritocracy is the best means for doing so even if it leads to lower Social Mobility in the long run.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

Why Progress and Upward Mobility should be the goal, not Equality

The Pathway to Success (first of three articles in series)

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Gregory Clark has two great books on social mobility. It’s changed less than we think over time.