Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

When we talk about technological innovations, the last thing that pops into people’s heads is Medieval peasants in Europe. Compared to today, Medieval peasants struggled in the mud working with primitive technology and working excruciatingly hard just to survive. The only changes in their lives were the periodic bad events: famines, drought, and war. The best that a Medieval peasant could hope for was to avoid those three events for their lifetime.

Progress was simply not something that Medieval peasants thought about.

Despite the terrible circumstances that Medieval peasants lived in, or perhaps because of it, Medieval Europe was one of the most dynamic societies that had yet evolved on planet Earth. I will leave the accomplishments of Medieval Europe to another article. This article is about the foundation of Medieval Europe: increased agricultural productivity from a new farming system.

Note: The term “ Medieval farming” is a bit deceptive. By Medieval farming, I mean farming practices in Northwest Europe that were innovated during the early Medieval period (likely between the years 700 and 900) and then gradually spread outward to much of Northern Europe during the late Medieval period. The term excludes most farming systems during the Medieval period.

Medieval farming practices mainly impacted the following modern-day nations:

Belgium

Netherlands

Northern France

In the late Medieval farming practices then gradually expanded to the following modern-day nations:

England, from southeast to northwest

Germany, from west to east

Portions of Central Europe that were settled by Germans

Medieval farming practices had very little impact on farming practices in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Asia, and the rest of the world. Even Eastern Europe was relatively unaffected by the practices.

Note: the following description and graphics were adapted from A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart. You can find a more detailed summary in my online library of book summaries.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

How American farmers mechanized agriculture in the 19th Century

The back story

To understand why Medieval farming was so innovative, you need to understand what came before it. For thousands of years, societies in Europe, the Mediterranean, and much of the Middle East used an Ancient subsistence pattern based upon:

the scratch plow (or ard) and hand tools

two-year crop rotation with:

wheat as the main crop

15 months of fallowing (i.e. leaving a field unplanted so it can recover nutrients)

Allowing cattle and pigs to graze in the wild during the day and penning them up at night in the fallowed field. Their manure effectively transported nutrients, particularly nitrogen, from wild plants to the fallowed field.

Pack animals for transportation

The inherent inefficiencies of this system undermined the possibilities of long-term growth in per capita GDP.

The Medieval farming system

The Medieval farming system originated in Francia (modern-day Belgium, Northern France, and the Upper Rhine). The geography of the region played a profound role in determining why this region could jump to a new farming system.

Many people who focus on modern technologies regard farming as “simple” technologies and skills. Farming is not the slightest bit simple, although each individual technology and skill was often quite simple. In combination, however, it was anything but simple.

Medieval European farming was, in fact, a very complex system involving:

Domesticated plants that were bred (usually unintentionally) over many generations, particularly:

Wheat

Barley

Oats

Rye

Domesticated animals that were bred (usually unintentionally) over many generations, particularly:

Cattle (mainly for meat and milk products, but also for farm work early in the Medieval period)

Horses (mainly for farm work later in the Medieval period)

Pigs (mainly for meat)

Sheep (mainly for wool for clothes making)

Small livestock (geese, chickens, etc)

A Three-fields crop rotation that maximized the output of all the above.

Gathering wild plants, particularly wood for construction and home heating.

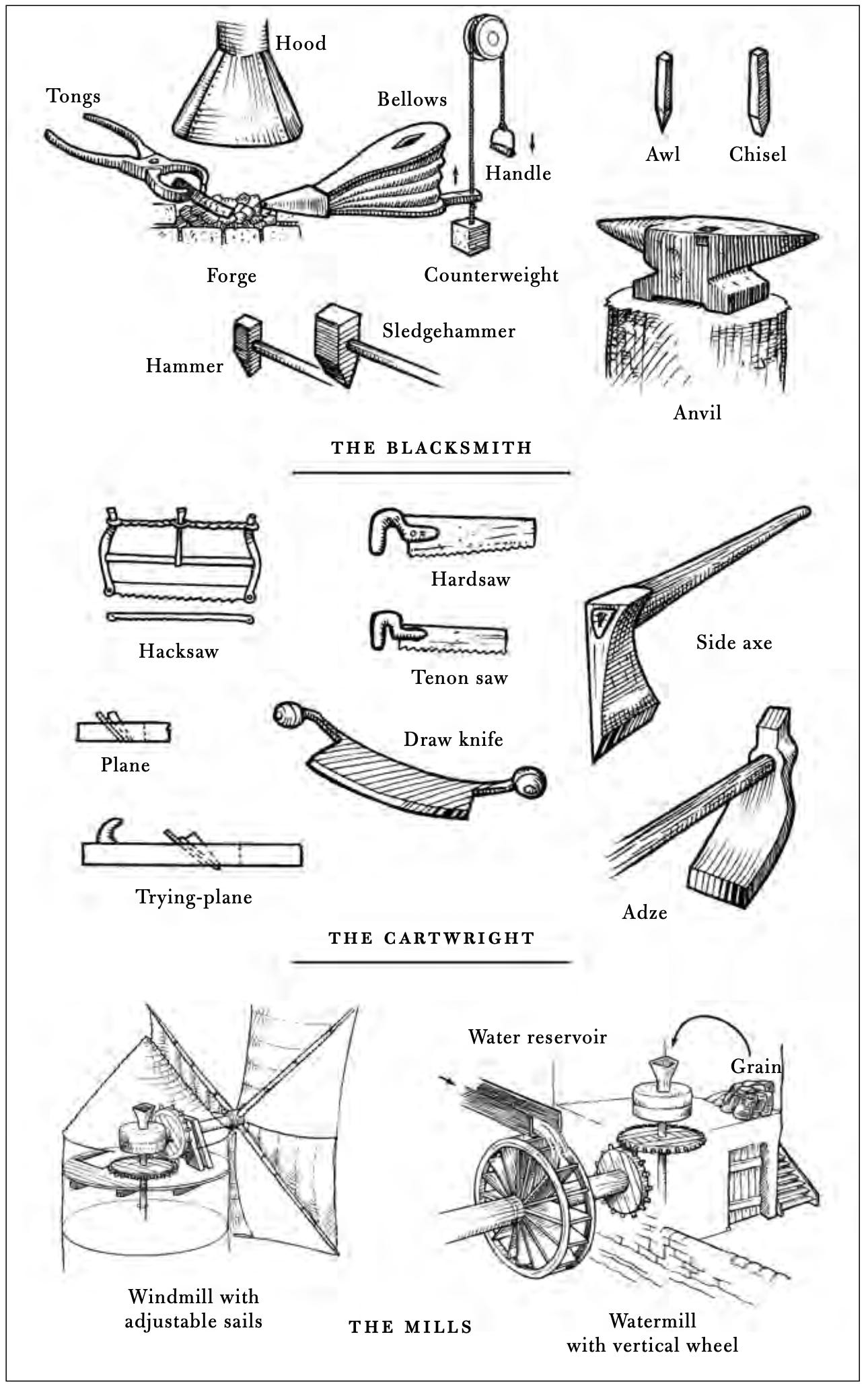

Dozens of technologies (see below)

The necessary skills to use those technologies properly

A carefully choreographed calendar of annual activities (see spikes at bottom of the following graphic).

A cuisine that combined all the agricultural produce into a variety of at least somewhat nutritious meals.

Raw materials for producing clothing for the family from wool, flax, and hemp. Most of this clothing was produced at home by women.

A key part of the Medieval farming system was also village and market towns, where:

Surplus food could be purchased and sold

Metal tools and wagons could be manufactured by local artisans

Domesticated animals could be purchased for farm work.

Farming starts with biology

Farming is essentially the attempt to transform energy from the sun and other natural resources (soil, water, organic nutrients) into food that enables humans to survive and reproduce. It is so fundamental to human survival that all pre-industrial societies were organized around this activity. Agriculture was not just a quest for individual farmers. It was a quest for the entire society.

This quest must start with biology, particularly domesticated plants and animals. The key plants were barley, rye, and oats, while the key animal was the horse. I will write more on this in another article.

A key part of the Medieval farming system was the introduction and diffusion of new crops. Migrants from the Fertile Crescent, where agriculture was invented, brought grains (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, and barley) and pulses (lentil, pea, chickpea, and bitter vetch) to Northwest Europe. Each of these crops had very specific growing conditions.

Medieval farmers added hay, rye, and oats. These crops were so important to the Medieval farming system that I will write a separate article about them.

Perhaps even more important, Medieval farmers applied the horse to agriculture and transportation. Just as important, Medieval farmers improved and diffused technologies that brought out the full potential of horses: the horse collar, horseshoe, stirrup, wagon, and cart. The horse and its associated technologies are so important to the Medieval farming system that I will write a separate article about them.

For now, it is important to understand that without the widespread use of hay, rye, oats, horses, the horse collar, horseshoe, stirrup, wagon, and cart, the Medieval farming system would have been far less productive.

The Three-field Crop Rotation

Another key breakthrough in Medieval farming was the Three-field system of crop rotation. Whereas the Ancient Two-field system from Greece and Rome left half of the farmer’s land fallow (empty of crops) for 15 months, the Medieval system, shrank that down to only one-third of the land, for two separate periods of 15 months and 8 months. This led to a sizeable increase in the amount of productive land. The result was a substantial increase in the food surplus that farmers produced.

This may not seem very important, but remember that farmers had to devote their food to many purposes. Farmers must produce enough food:

For himself to survive.

For his wife and children to survive, so that society can reproduce.

(in some cases) For elderly or handicapped persons who cannot support themselves

To pay taxes and land rents to the local Lord

To pay tithes to the Church

To store his best seed to sow for next year’s crop (with enough left over to account for destruction by pests)

Then on top of all that, the farmer had to be ready for droughts, excess rain that destroys a harvest, and destruction by war. With all of that, it is really a wonder that farmers could survive at all. But they clearly had an enormous incentive to do so.

Only after subtracting all of that food out can we really talk about a food surplus (at least from the farmer’s perspective). The farmer had almost no ability to lower the amounts that must be devoted to all the above, so the only way to increase food surplus was to produce more. Even a 5% increase in productivity could lead to a doubling of the food surplus that could be sold in market towns.

Technologies Used

The Medieval farming system relied on innovation and improvement of an entire suite of agricultural and transportation technologies. All these technologies were so important that I will devote an article to how they all came together in a system. As a sneak peek, you can see this graphic below.

Surviving Winter

A key problem for Medieval farmers, and all farmers in Temperature latitudes, is ensuring that they, their families, and their domesticated animals can survive winter. Winter is a time when virtually no crops can grow, so the family must subsist on stored foodstuffs. The family must also burn huge amounts of wood to stay warm at a time when:

it is difficult to move around.

the body burns a significant amount of energy just keeping warm

This requires a significant amount of wood-cutting before the winter to ensure that the family does not run out of wood. Typically, this was a major activity by the men and young boys during the slack period between times when the crops needed tending (see spikes at the bottom of the first schematic diagram above).

Ironically, the most dangerous period for a farming family is during the spring, when winter stores are almost exhausted and crops cannot yet be harvested. This was the “starving season” when entire villages were just barely surviving. This season was particularly bad if the previous summer resulted in a bad harvest or if the region had a war. A few bad harvests in a row could lead to progressively worse springs that led to serious malnutrition or even starvation.

Estimating productivity increases

Estimating productivity of specific farming practices in history is fraught with hazards. There are great geographical variations due to weather, soil, and availability of water. There can be substantial variations even with a relatively small plot of land. There are also substantial variations between seasons. There is also productivity as measuring by land, human labor, animal labor, seed multiples, and agricultural inputs.

In A History of World Agriculture, Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart make some plausible estimates that show that Medieval farming practices did lead to a substantial increase in productivity. They estimate that a family of five needed 3 hectares of arable land to support themselves using the Ancient Farming system. After subtracting out fallow and other “wasted” land, this comes to 6-7 hectares. Surplus food would only come from more land.

Using the Medieval farming system, however, that same family of five could produce 20 quintals net of wheat, enabling them to sell 10 quintals in the marketplace. This would likely enable a tripling of population density. So the Medieval farming system enables a far higher food surplus than the Ancient farming system.

Did Medieval farming lead to progress?

The Medieval farming system led to a very impressive increase in farming productivity. This in turn led to a great expansion of Latin Christendom, that I will discuss in a later article.

But did Medieval farming lead to progress?

I am afraid the answer must be “No,” if you define progress as “the sustained improvement in the material standard of living of a large group of people over a long period of time” as I do.

It is very clear that Medieval farming did not lead to an increased material standard of living for the masses. Virtually all the increased food production went to:

Having more babies, who ate away much of the surplus (see Thomas Malthus for more details)

Forced extraction of the food surplus by elites who dominated the political, economic, military, and religious institutions. They typically did so via taxes or land rents (because they owned most of the land).

In other words, the farmer did all the work, and the elites got all the benefit.

Was it all worth it?

The Medieval farming system was the result of hundreds of years of experimentation, innovation, and brutally hard work by millions of farmers. It led to little tangible increase in the standard of living of those same farmers. They managed to survive a short life full of toil, but little else.

But the efforts of Medieval farmers were not in vain. Medieval farmers laid the foundations for future farming systems that, in combination with the other Five Keys to Progress, generated material progress for the masses.

But that is the topic of future articles…

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

How American farmers mechanized agriculture in the 19th Century

If you are interested in the intricacies of this and other farming systems, you can find a more detailed summary of A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in my online library of book summaries.

Based upon your recommendation and reviews, I bought Mazoyer & Roudart. The book is simply phenomenal, providing a better picture of agricultural and social revolutions (and how they are interconnected) than anything I have ever read. 5 stars!

The odd thing though is how two such brilliant researchers could be so wrong on their prognostications and recommendations. The contrast is shocking. Great historians lost in a dysfunctional anti-progress worldview.