Farming in Commercial societies (1500-1800)

And how it generated the food surplus to trigger human material progress

By the year 1500, Northwest Europe had undergone three distinct agricultural revolutions:

The Neolithic “slash-and-burn” farming system, which was imported by Horticultural migrants from the Middle East.

The Ancient farming system, which was the system used during the times of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and the Dark Ages

The Medieval farming system, which was unique to Northwest Europe. It was invented sometime between 700 and 900 and lasted until the 19th Century. This system roughly doubled farming productivity compared to the previous Ancient farming system. Unfortunately, this was still not enough to generate material progress for the masses.

The Medieval farming system consisted of:

Heavy plow, harrow, and roller pulled by

Oxen (in the early period) or horses (in the late period)

Three-field crop rotation with:

Wheat, rye, barley, and oats as the staple crops

15 and 8 months of fallowing (i.e. leaving a field unplanted so it can recover nutrients)

Horse-drawn carts and wagons for transportation

But this was just the beginning. Northwest Europe and the regions settled by people from that region experienced multiple agricultural revolutions. This is in startling contrast to virtually every other region in the world.

In every other agricultural region on the planet, the basic subsistence patterns for each agricultural region had evolved by about 500 BCE. While there was a great deal of geographical variation, subsistence patterns in all other regions evolved very little between 500 BCE and when they were first exposed to European conquest after 1500. That is stagnation for 2-8,000 years!

Even after European conquest, there was typically very little change in subsistence patterns outside Northwest Europe and North America until the late 20th Century. And outside of agricultural regions, change was even slower. Many societies were effectively trapped in subsistence patterns defined by their society type, and there was no possibility of change.

Note: the following description and graphics were adapted from A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart. You can find a more detailed summary in my online library of book summaries.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

First a note on terminology. This article is about a fourth agricultural revolution that swept through parts of Northwest Europe starting around the year 1500. For the purposes of this article, I will call it “Commercial farming” even though it is technically more accurate to call it “Agrarian Systems without Fallowing in the Temperate Regions.”

I use the term “Commercial farming” in this article to denote specific farming practices in Commercial societies, such as Flanders, Netherlands, and southeast England roughly between the years 1500 to 1800. These changing farming practices are sometimes called “The Agricultural Revolution” in the historical literature.

I also believe, though I must admit that there is little documented evidence to support my claim, that Northern Italy pioneered many of these techniques. It is very clear from the historical record that farming practices of Late Medieval Northern Italy were unusually productive, but I cannot find any detailed studies in English.

I prefer not to use the term “The Agricultural Revolution” because it implies that there was only one Agricultural Revolution. In fact, a key distinguishing characteristic of farming in Northwest Europe is that it went through at least six distinct Agricultural Revolutions. After 1800, farming systems in wealthy nations Western went through a perpetual revolution that made them increasingly commercialized. Each is described in separate articles in this column.

The Commercial farming system

Many people who focus on modern technologies regard farming as “simple” technologies and skills. Farming is not the slightest bit simple, although each individual technology and skill was often quite simple. In combination, however, it was anything but simple.

The elimination of fallowing

A key innovation of Commercial farming was the elimination of fallowing. Fallowing was a common practice in Ancient and Medieval farming. Fallowing consists of leaving a portion of a farmer’s field empty of crops so that the soil is given time to regenerate vital organic nutrients, particularly nitrogen. This was commonly accomplished by domesticated animals (in the Ancient system) or humans (in the Medieval system) dispersing manure into the soil. Obviously, fallowing seriously undermines the short-term productivity of the soil by taking a significant portion of the farmer’s land without crops.

Commercial farming found a far more productive method for regenerating spent soil. Rather than leaving a third of their land empty, farmers began planting fodder row crops (such as clover and turnips) and seeded pastures. The result injected nitrogen back into the soil, while still producing a feed for domesticated animals. This allowed farmers to eliminate the 15-month and 8-month fallowing in the Medieval farming system.

In particular, the replacement of fallowed land with seeded pastures greatly increased hay production. Hay was critical for getting domesticated animals through the winters when the family and their animals needed to subsist on their stored food. Hay was easy to store in barns. When domesticated animals could eat hay over the winter, their chances of survival increased dramatically. Rather than slaughter their animals in the early winter for consumption, farmers could keep their animals alive through the winter. This enabled their number of domesticated animals to grow year after year.

Commercial farming practices enabled roughly a doubling of:

The number of livestock (and their survival through the winter)

The production of manure (from the doubling of livestock)

Cereal yields (from the doubling of manure production)

Animal draft power

Production of animal byproducts (meat, milk, wool, hides, etc). These animal byproducts formed the bedrock of farming exports to growing cities.

Remember that farmers in Agrarian societies hovered on the edge of subsistence. They had to grow a large amount of crops for themselves, and their family, to pay taxes, and for next year’s seeding. And he always had to worry about droughts, excessive rains, and war disrupting the harvest. Just getting through the winter and early spring was a major accomplishment for earlier farmers.

Only once all those amounts are subtracted out can we talk about a “food surplus.” The doubling of yield compared to the Medieval system is a very big deal, which was already a substantial jump up from Ancient farming. Now farmers had roughly four times the amount of food as their ancient ancestors. Of course, the increased number of animals consumed much of this surplus, but there was still a very sizable food surplus so that farmers did not have to worry about each harvest. They could now start thinking like businessmen, not subsistence farmers.

For the first time in history, farmers had a substantial and reliable food surplus to sell in the marketplace. This enabled the rise of Commercial cities where most of the period’s innovations took place. Without these sizable food surpluses, a constellation of dynamic Commercial cities would have been near impossible.

More on this in another article.

How far did Commercial farming spread?

Ironically, despite its vast improvement in productivity, Commercial farming did not spread geographically very rapidly. The practice started in Flanders and spread to the Netherlands and then southeast England, and then slowed drastically. Commercial farming practices slowly diffused through other parts of England in the 18th Century and scattered parts of Northern France and Rhineland Germany. But the bulk of France, Germany, Central Europe, Mediterranean Europe, and Eastern Europe were virtually untouched.

Even as late as the middle of the 19th Century, the bulk of Northern and Central Europe still used the Medieval farming system. It was only during the process of industrialization that farming practices began to rapidly change (which came first is a matter of great debate). And the Mediterranean regions were stuck in an even older Ancient farming system up until the middle of the 20th Century.

And no agricultural society outside of Europe adopted the Commercial farming system. So though the Commercial system was extremely successful in certain localities, it had a limited geographical impact.

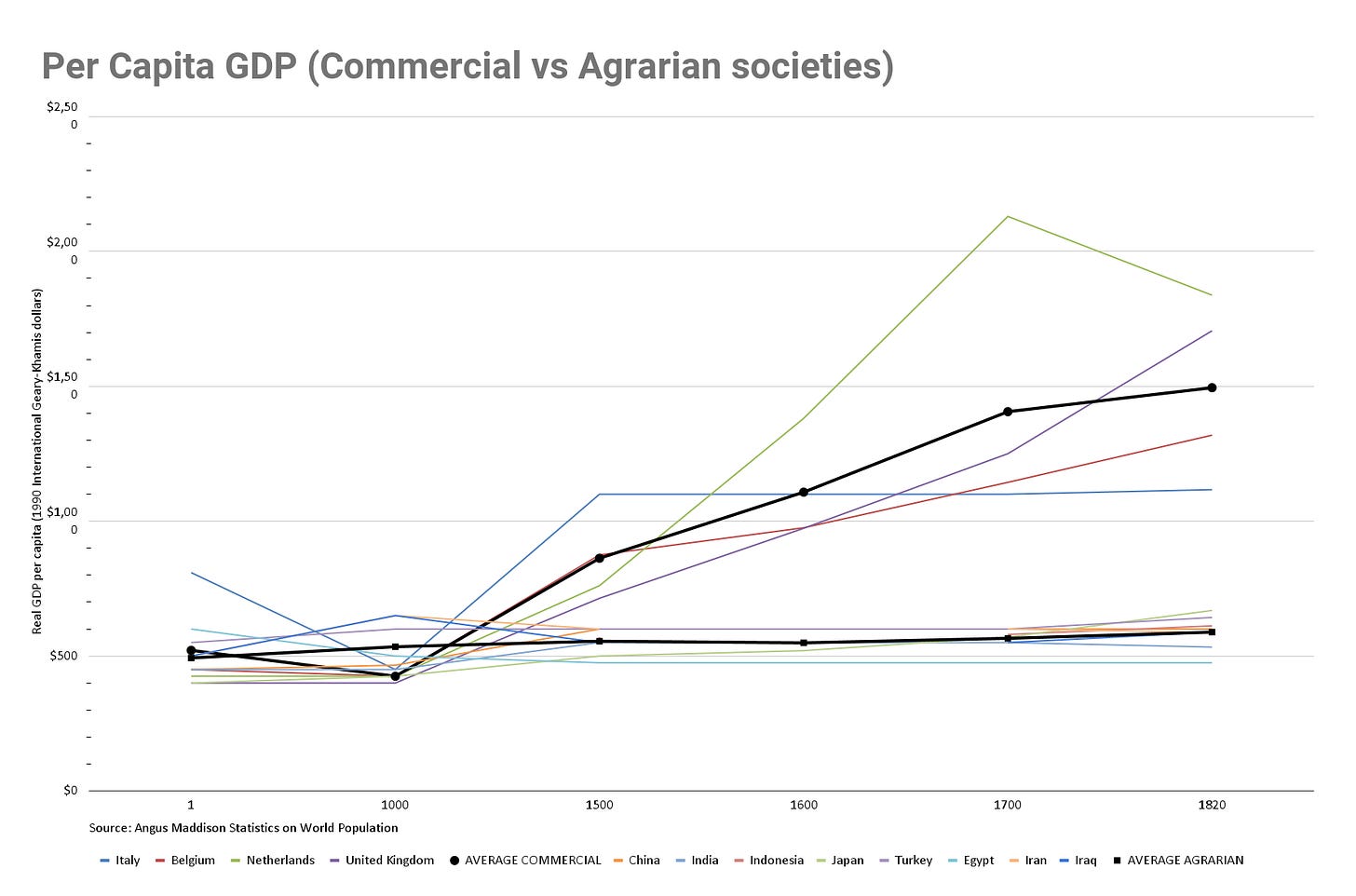

Did Commercial farming lead to progress?

Commercial farming practices did not create progress, but those farmers did finally invent the first Key to Progress: A highly efficient food production and distribution system. This allowed Commercial societies, such as Flanders, the Dutch Republic, and pre-Industrial England to zoom ahead of their competitors in agricultural productivity.

For very different reasons, Commercial societies were also able to invent the third Key to Progress: Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. Elites in Commercial elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses. This also allowed citizens to freely choose among institutions based upon how much they have to offer to each individual and society in general.

This meant that the food surpluses, which were far higher than in previous societies, were not simply expropriated by elites via taxes and land rents. Instead, the farmers exported their food surplus to emerging trade-based cities. This, in turn, enabled Flander, Netherlands, and England to urbanize rapidly (the 2nd Key to Progress). To pay for the food surplus, city dwellers need to innovate new technologies, skills, and organizations that generate a profit. This in turn led to the formation of a constellation of highly productive export industries (the 4th Key to Progress).

Commercial farming practices were the key reason why Commercial societies were able to invent four of the Five Keys to Progress. Because of those four keys, Commercial societies experienced “the sustained improvement in the material standard of living of a large group of people over a long period of time” (which is my working definition of progress). This was in contrast to all other societies in the world that had existed up until this time.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

If you are interested in the intricacies of this and other farming systems, you can find a more detailed summary of A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in my online library of book summaries.

Absolutely brilliant! You continue to be the leading insight on World Progress.

One point that's often called out in this era, and that I didn't see you address, is the appearance of New World crops. Above all, the potato. I've heard it said that potatoes have about 2-3x the yield per acre of wheat. I'm not sure how they differ in terms of labor intensity to cultivate and harvest, though obviously they at least require less processing than wheat to be palatable.

I don't really know. I'm inclined to be somewhat skeptical of these claims about the potato, since, after all, a lot of wheat was clearly still produced after its appearance, which probably wouldn't be true if the potato were just that much better. Maybe it's that the potato was valuable as a subsistence crop, especially in marginal lands (enabling rural population expansion), but not as a commercial crop (enabling the urbanization you describe).