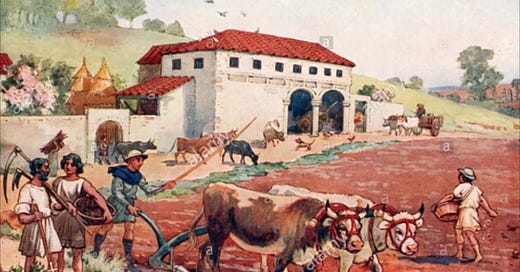

Farming in Ancient Greece and Rome

And why its inefficiencies made progress all but impossible

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

My Substack column is focused on human material progress. I believe that this trend did not start until a little after 1200 in Northern Italy and Northwest Europe. I do, however, believe that we must understand history before the year 1200 to understand the origins of human material progress.

In particular, we need to understand how societies produce enough food to eat. Material progress requires technological innovation, the acquisition of skills, and a diverse array of competing organizations. None of this is possible until humans overcome the most important constraint on progress: the need to acquire enough food to survive and produce from the natural environment.

In an entire series of posts, I have argued in favor of the utility of using the concept of Society types. It is important to recognize that there were very big differences between Agrarian societies. While historians tend to focus on political, military, religious, or cultural differences between Agrarian societies, I think that the fundamental difference was in subsistence patterns (i.e. how the lowly farmer produced enough food to eat).

This determined the amount of energy surplus that could be injected into the society and how the entire society was ordered. Before one can innovate, one must first eat. How humanity overcame this dilemma is key to understanding the origins of human material progress.

First, let’s take a look at agriculture in Ancient Greece, Rome, and the Middle East.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

Limitations of Ancient Farming

Note the following description was adapted from A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart. You can find a more detail summary on my online library of book summaries.

For thousands of years, societies in Europe and the Mediterranean used a subsistence pattern based upon the scratch plow and the two-year crop rotation. While it is unclear exactly when this subsistence pattern came into being, we do know that it dominated Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and much of the Middle East.

Note that this article does not cover farming systems of South Asia, East Asia, or Southeast Asia, which typically focus on rice. This made their farming systems very different.

The foundation of this Ancient subsistence pattern was the scratch plow (or ard as it was known in Ancient times). In some ways, it is a misnomer to call the ard a plow, as it does not actually plow, i.e. turn over the soil.

The scratch plow functions somewhat like an oversized digging stick that is dragged along the ground to create a long, shallow trench. The main purpose is to make it easier for farmers to later break up the soil using hand tools. The actual turning over of the soil was accomplished using spades and hoes.

Ancient farming systems used the two-year crop rotation. The two-year rotation was based on planting winter wheat in November and then harvesting the crop in July. Since this wheat crop depleted nutrients from the soil, farmers were forced to leave their fields as fallow for the following 15 months. Fallowing was critical to renew the fertility of the soil. Nitrogen, in particular, is rapidly depleted with this farming process.

During this fallowing time, the fields were not used to grow crops at all, but the fields were worked. Farmers allowed wild grasses to grow, but they regularly plowed and hand-worked the soil using the hoe and spade to keep down weeds. But during this long 15-month period, no food was directly being produced.

This meant that the farmer’s fields were productive only about 37.5% of the time. This kept crop yields very low in comparison to later agricultural systems. Because bread supplied more than three-quarters of the population’s calories, this low productivity was a fundamental constraint on progress in these societies.

Even worse, this agricultural system meant that only a small portion of the farmer’s land could be devoted to growing crops. Farmers generally devoted their most fertile land to growing wheat, but the majority of the land was left as pasture or forest. The forest was necessary for lumber for construction purposes and firewood for heating homes. The pasture was necessary for growing grass to feed the cattle that pulled the scratch plows. Finally, a small garden was needed for growing flax and hemp for clothes and vegetables, and legumes, for cooking porridges and soups.

While the cultivated fields were left fallow, cows and other livestock fertilized the fields with their manure. Each morning the farmers drove the livestock out to the pasture to eat. Before sunset, the farmers then drove the livestock back into the fallowed land which was surrounded by fences. Overnight, the livestock would drop manure randomly throughout the fallowed field. In this way, the livestock transferred nutrients from the pasture land to the cultivated land via manure.

At the beginning of the summer, many farmers supplemented this practice by driving their herds into the mountains where they could feast on wild pastures at higher elevations before returning after the wheat was harvested. Without this critical replacement of nutrients, the entire Ancient farming system would have collapsed within a few years.

The tools used within this farming system were surprisingly primitive. In addition to the scratch plow (usually pulled by two-to-four oxen) farmers used the spade, hoe, thresher, stone mill, mortar, and pestle (for making flour). Except for the scratch plow, these tools were much the same as had been used by Horticultural societies (i.e. farming with hand tools) for millennia.

Transportation was even more primitive. The Greeks and Romans, despite all of their achievements, lacked wagons and rarely used carts. Their primary means of bulk transportation were pack mules and donkeys. Rather than pulling cargo, pack animals carry cargo that has been strapped to their backs. While economical, this method had serious limitations. This made it very difficult to transport hay and manure to fallowed land and wheat to town markets.

Lacking large food surpluses and having major transportation limitations, the Ancient Greeks and Romans were forced to disperse to be close to their land. The vast majority of people in those societies lived in villages with no more than a few hundred people. Quite a contrast to what most people imagine Greek and Roman life to have been!

In all, this Ancient subsistence pattern was not very productive. It has been estimated that a family of five would need 40 acres of land to support its food needs. And that land would need to be divided 4/5/1 between cultivated land, pasture, and forest. Many areas would not have the correct proportions, so larger farms would be necessary to support one family.

So what enabled Ancient Greece, Rome, and the Middle East to build such splendid cities? Imported food and slavery. The large capitals of the Ancient era were undoubtedly largely supported by imported food. Rome imported grain from Egypt, while Athens imported grain from the Black Sea. Probably more important in small cities was slavery. Slaves were not allowed to reproduce, so they would guarantee a food surplus. Slaves were effectively a different species of beast of burden.

While the Mediterranean region and Europe were highly constrained by limited agricultural production, the same can be said for all the other Agrarian societies of Eurasia. By about 500 BCE, the basic subsistence patterns for each region had evolved. While there was a great deal of geographical variation, most regions evolved very little between 500 BCE and when they were first exposed to European conquest after 1500.

Geographical constraints seriously limited the innovation of subsistence technology and organizations. Even the most complex societies in East Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean had basically the same subsistence pattern in 1500 as they had 2000 years previously.

Could Rome Have Industrialized?

Some Progress Studies researchers and economic historians have debated whether Ancient Greece or Rome could have industrialized. Of course, such alternate history scenarios are impossible to answer with any certainty, but I am confident that the answer is “No” for the following reasons:

The Ancient two-field farming system was nowhere near productive enough to support industrial cities. This ensured that the rate of growth of per capita GDP was at or near zero.

Widespread use of slavery may have made cities possible, but they also undermined labor productivity. There is simply no way that slaves can be as productive as free labor for long periods of time. Because slaves do not enjoy the benefits of their labor, they have no incentive to work harder or, more importantly, innovate more productive means of doing their jobs. This undermines the possibility of improving the growth of per capita GDP.

The overall technology suite was much too simple to support an Industrial society. A huge number of technologies needed to be innovated before industrialization in any society was possible.

I am very skeptical that any Agrarian society would have been able to innovate all of them, even given an unlimited amount of time. Agrarian societies simply stifled innovations, except in the field of:Military technology and organization

Elite consumption and entertainment

Extractive organizations designed to extract the food surplus from the peasantry.

For these reasons, I believe that no Agrarian regime, particularly one based on the Ancient two-field farming system could possibly have industrialized.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

If you are interested in the intricacies of this and other farming systems, you can find a more detailed summary of A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in my online library of book summaries.

Just discovered this Substack. This post is very interesting, subscribed.

Haven't had a chance to look at your back posts yet, but question: have you read "When Histories Collide" by Raymond Crotty? It's an interesting book that never seems to have received much notice, perhaps because Crotty died on the eve of its publication and therefore very little was done to publicize it, and I think it only had a single print run. But it sits on my bookshelf.

Crotty was a farmer-turned-economist, which naturally leads to a unique perspective. Perhaps a bit crankish, but that doesn't mean he was wrong about everything. I found the most interesting part of the book to be the early chapters, which offered a certain farmer-economist view of ancient history, especially in the West.

Regarding the productivity of agricultural slaves:

One mathematical observation I took from Crotty about slave agricultural labor is that slave-owning elites can derive gains (and the ancient Mediterranean civilizations probably did so) by burning through the slave population by refusing to support unproductive dependents.

To expand: since a free farmer and his wife and children, even at zero rate of population increase (which means something like 4 births, 2 children that survive to 18), likely consumes more than double the calories of a single prime-age man, there is a surplus to be extracted if you can get a prime-age man to work at a low enough wage that he can't support any dependents.

The trouble is that a free prime-aged man probably will not toil at agricultural labor if the wages are so low that he cannot hope to even support a wife. He'll sooner become a beggar, pirate, bandit, soldier, poacher, etc. Slaves in general might be less motivated than free men and therefore produce less, but if the system of coercion is efficient, they can be forced to accept a much lower wage that is subsistence for themselves only. Though to sustain this system, you will need to continually capture new slaves.

Crotty spends a lot of time on the notion that the stock of "arable land" is dynamic, that marginal land may be brought under cultivation by a new technological or social development. So he argues a major way this slave surplus is expressed is by bringing certain marginal lands under cultivation that are too poor to support a family under the current set of agricultural technologies, but sufficient for a single prime-age man to produce a surplus.

EDIT: I just took another look at your post and saw that you had a sentence about slaves not being allowed to reproduce. Ah well, consider my comment an expansion on that idea.

Great post!