How the suburbs accelerated integration and upward mobility

And why urban advocates for density refuse to acknowledge this fact.

Most Urbanist writers, thinkers, and activists are highly educated and on the ideological Left. Most are Center-Left, but many are even further to the Left. They share:

An aesthetic preference for dense European-style cities. This includes a love for mass transit and mixed-use buildings.

An aesthetic disdain for American-style suburbs, which they label as “sprawl.'“ This includes a disdain for cars, highways, and single-family residences with spacious front and backyards.

Having lived in Europe for many years (London and Copenhagen), I also love European cities. Since the vast majority of European cities go back 1000 years to the High Middle Ages or 2000 years to the Roman Empire, they a veritable museums of history. I love the architecture and the history that is associated with each architectural style.

But I also love to live in American-style suburbs, and based on polling data and revealed preferences of the neighborhoods they choose to live in, most Americans do as well. While there was a burst in young people moving to dense urban centers in the Northeast and Pacific Coast in the 2010s, that now appears to be a temporary deviation from the long-term trend of suburbanization.

In an attempt to change people’s minds, Left-of-Center Urbanists heap on the scorn for sprawling suburbs. One of the most known in this genre is Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States by Kenneth T. Jackson. This was not just any book. It really was a milestone in Urbanist history and one that Urbanists still greatly respect.

Crabgrass Frontier won:

the prestigious Bancroft Prize as the best history book for the year.

the Francis Parkman Prize from the Society of American Historians for the best American history book for that year.

I read the book back in the 1990s and was impressed by it. I still believe that the book is well worth reading. Over time, however, as I learned more about how cities worked, I realized that much of the arguments are based on ideological assumptions about how cities should be rather than an analysis of how they really are and why they came to be.

Many of the facts presented by Jackson and other Left-of-Center Urbanists are true, but they are obviously mining the data to find ammunition for what is essentially an aesthetic preference for density. Many Urbanists claim that the reason why American suburbs are so widespread is bad public policy has changed people’s incentives for where they want to live.

One of the most misleading arguments Urbanists make is to associate suburbs with segregation, particularly racial segregation. For any American who has Left-of-Center ideology, there is nothing worse than for something to be associated with racism and racial segregation. In their mind, racial segregation is the original sin of the suburban lifestyle.

But is this really the case? Are suburbs really associated with segregation?

The Great Realignment in American society

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

I believe that the opposite is true.

The American suburbs played a key role in desegregation.

To understand why, one must discard the idea that the main cleavage in American society is race. In fact, for the vast majority of American history, Americans were primarily divided by ethnicity and religion. And suburbanization played a key role in eliminating most of these divisions.

If you enjoyed this article, you might enjoy reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

America before 1930

Today, we like to claim that America is unusually diverse and more diverse than any time in our history.

I disagree.

The United States before 1930 was far more diverse than today based on culture, ethnicity, religion, and region. The problem is that most Americans today almost immediately think of race as the only form of diversity. When you expand the concept of “diversity” into culture, ethnicity, religion, and region, then America was far more diverse in previous centuries.

Today many people think of diversity as being part of one of the four racial groups: Whites, Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics.

Before World War II, however, most people outside of the Deep South thought in terms of ethnicities and religions, rather than race. Outside of the Deep South, people did not even think in terms of race very much.

There were no White Americans; there were Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, German Americans, Norwegian Americans, Polish Americans, and Irish Americans. Each of these ethnic groups (and many others) was heavily concentrated geographically in a small portion of the nation, and each group tended to have local self-governance.

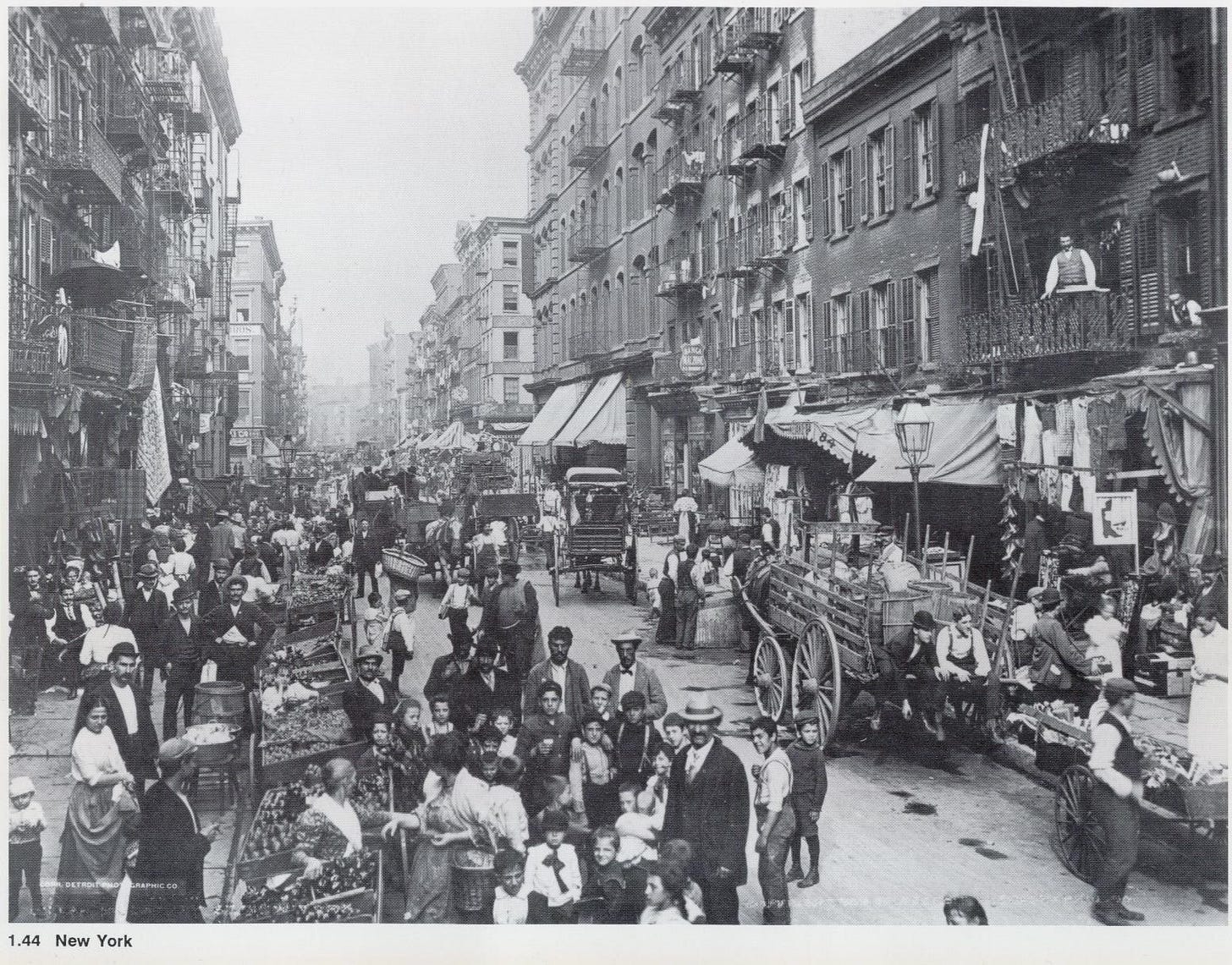

Outside of the South American cities were jumbles of ethnoreligious neighborhoods, each highly segregated from the other ethnoreligious groups. Because of the decentralization of the American political system, each of these ethnoreligious groups had de facto autonomy and rarely associated with others outside their own group.

New Deal Democrats Promoted Sprawl

Today, “sprawl” is perceived as a bad thing, particularly by those on the Left. Sprawl is typically defined as the spreading of urban developments onto undeveloped land near the city. This trend is almost universally derided by those on the Left as a bad thing that undermines our quality of life and our natural environment. Promoting density and limiting sprawl is now considered one of the most critical goals of urban design.

Ironically, we forget that it was Democrats who actively promoted the very suburban developments that are so derided today. In the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, New Deal Democrats actively promoted home construction and ownership on the outskirts of urban regions. They also founded institutions – the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Fanny Mae, and Freddy Mac – that made it easier for working-class families to purchase those homes. The federal government allowed (and still allows) workers to deduct the interest on their mortgage payments from their taxes. This is a substantial stimulus on home ownership. Most importantly, the federal, state, and local governments erected few barriers to building homes.

These policies were particularly important because America was experiencing a post-war Baby Boom. All these new families needed someplace to live, and new housing construction on the outskirts of metro areas was deemed the best solution to the problem.

During the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, the suburbs popped up like mushrooms in the forest. The result was a fantastic increase in the standard of living of the American working class from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. Certainly, a growing economy, strong trade unions, and limited foreign competition played important roles, but one should not underestimate the importance of affordable housing.

Rather than being cramped up in small, urban apartments in ethnically segregated neighborhoods, young working-class families could buy new, much larger single-family residences in brand-new suburbs. The government encouraged suburbanization by constructing new freeways to make transportation to and from those suburbs easier, faster, cheaper, and safer.

Integration of Ethnicities in Suburbs

Suburbanization played a key role in promoting ethnic and religious integration. World War II and the following post-war economic boom witnessed a profound change in the geographical dispersal of American ethnic groups. Before World War II most ethnic groups were highly concentrated geographically.

What this effectively meant was that ethno-religious groups were highly segregated until World War II. If those levels of ethno-religious segregation had continued during the post-war economic boom, it would have produced great inequalities between groups.

Ethno-religious groups living near factories would have prospered, while those living far from the factories would have missed out on much of the progress. The massive amounts of construction of single-family residences on the outskirts of growing metro areas ensured that this did not happen.

After World War II, young families from previously ethnically-segregated neighborhoods in the cities moved to brand-new houses in the suburbs. All the people from those segregated urban neighborhoods suddenly lived together in the same suburban neighborhood. Not surprisingly, many of them fell in love with each other, got married, and had children.

After a few generations of this process, ethno-religious diversity and segregation among whites melted away. Just as important, those young families enjoyed the benefits of strong economic growth.

Genetic and cultural mixing meant that all these ethnic and religious minorities fused until they became what we now call “Whites.” American unity and integration were stronger than ever. Without the growth of the suburbs, ethnic and religious segregation would have persisted.

Tragically, in most parts of the country, Blacks were left out of this process of integration, so legal and cultural racial segregation remained (while Asians and Hispanics were still relatively small in number). Only with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, did racial segregation in housing begin to diminish.

Housing Affordability Before 1970

For all Americans, though, the period between World War II and the early 1970s was one of widely-shared prosperity. Affordable housing played a key role in that widely-shared prosperity. Without suburbanization, this post-war prosperity would not have been as widely shared, and America would be far more segregated along ethnic and religious lines. Massive housing construction in the suburbs played a key role in housing affordability. This affordability meant that typical working-class families could afford to purchase a modest house for their families.

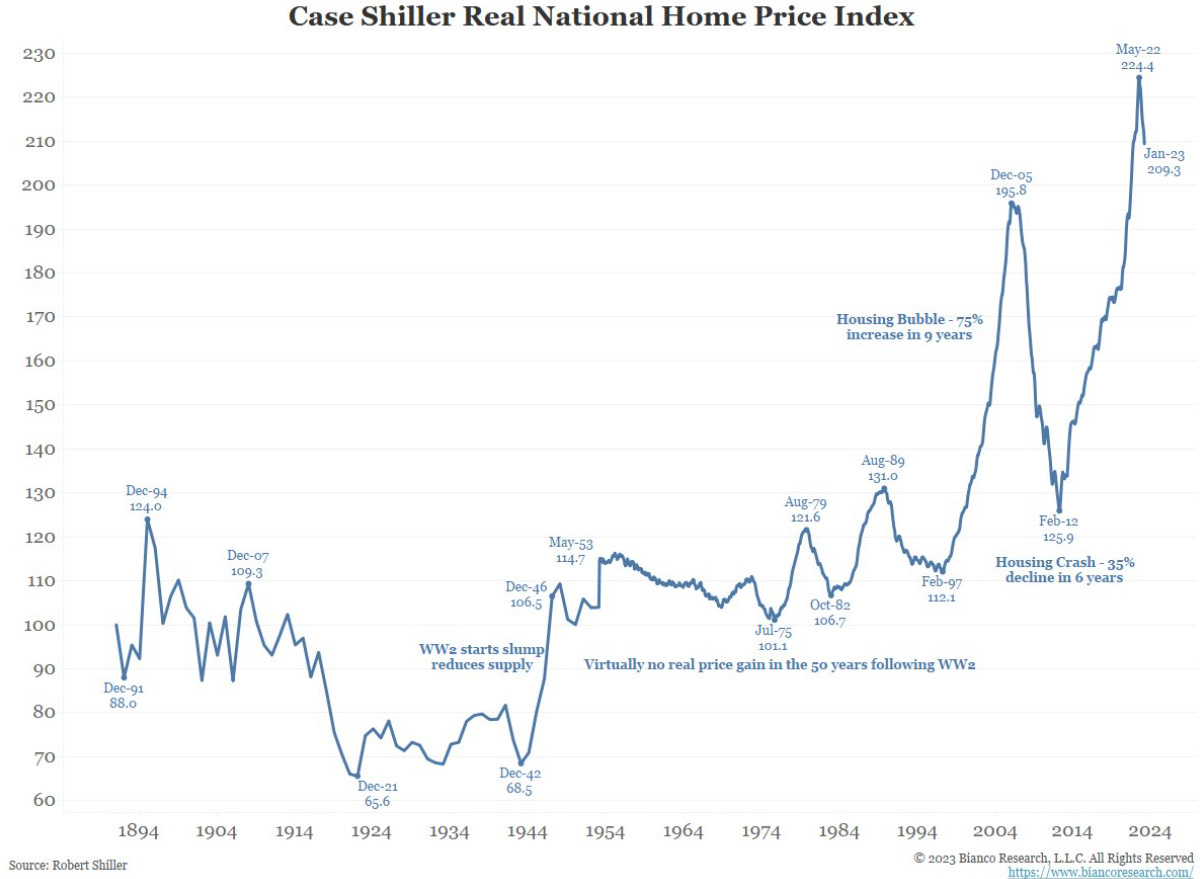

Housing inflation is a relatively new phenomenon. Until 1970, housing prices did not vary much from the core rate of inflation. This made housing affordable across the nation.

A useful means of measuring housing affordability is the ratio between the median cost of a house and the median family income within that metro. In 1969, virtually every metro in the United States had a ratio of 3.0 or less. The national average was 1.8 (Antiplanner, 2020). The below graphic is based on average earnings, rather than median, but it gives a pretty clear historical trend.

At that point, housing in the United States was affordable everywhere, even in the wealthiest cities. Though we do not have good housing price data from before that time, there is every reason to believe that this had been the case throughout American history.

Then, in the 1970s, something began to change radically. In a few key metro areas, housing prices began to increase far more rapidly than median family incomes. I explain why in my other articles on housing (listed at the bottom of this article).

This post is part of a multi-post series on Housing:

If you enjoyed this article, you might enjoy reading my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

I think you must have left off part of the article: I don't see any argument why suburban growth is better than higher urban density.

Remember an older guy telling a story from the late 70s/early 80s. An outside consultant was talking about a possible project for their city. He took the woman aside and explained, "this isn't going to work. You have the Greeks and Italians sitting beside each other."

"YOU HAVE GOT TO BE KIDDING ME"!