How progress spreads to neighboring societies

It is also about proximity to other societies

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my articles on related posts:

This is my fifth post on the role of geography in the history of human material progress. I would recommend reading the first, second, third, and fourth posts before reading this one.

In previous posts, I discussed how physical and biological geography has impacted human material progress. In this post, I will discuss human geography. More specifically, I will discuss how neighboring societies had an impact on development.

Societies often develop by copying technologies, skills, and social organizations from other societies. And military conquest by other societies can seriously set back long-term development. Because of those two facts, neighboring societies have a major impact on societal development.

Geographical Distance

Geographical distance has always been a barrier to the diffusion of progress. Before the advent of large ocean-going sailing ships, societies that were far away from each other rarely came into contact. We have already seen that the development of North America and South America was seriously constrained by a lack of contact with more complex Eurasian societies before the year 1500. The same can be said for Sub-Saharan Africa, New Guinea, and Australia. It is likely that if these regions had been closer to Eurasia, particularly Northwest Europe, they would have developed far more complex societies.

Societies on the Eurasian continent were able to develop at a far more rapid pace because they came into far more frequent contact with each other. Innovations in one society could be noticed by traveling merchants and then brought back to their homeland. Just as important, because the Eurasian societies were in constant military competition, any laggard society would be forced to copy more complex technologies, skills, and social organization or risk annihilation through conquest.

Fortunately, today we live in a world where transportation and communication technologies make the barrier of geographical distance easier to overcome than ever before. Most people on the planet now have relatively easy access to modern transportation and communication devices that were inaccessible to all but the wealthiest just a few generations ago. Mobile devices, in particular, have diffused across the world with amazing rapidity. In doing so, they have transformed the lives of so many previously poor people by connecting them.

But it is important to realize that geographical distance still plays an important role. Rural regions located far from trade-based cities often lack transportation and communication infrastructures. Inland regions of South America and Africa are often very remote from navigable rivers and container ports. Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, lacks a robust electrical grid capable of powering modern communication devices reliably.

Cultural Distance

Another barrier to the diffusion of technologies, skills, and social organizations is cultural distance. Cultural distance is a measure of similarity between people based upon the culture that they were born into. In general, cultural distance aligns with geographical distance, but due to large-scale migrations, they sometimes differ substantially.

For example, the English are culturally similar to their neighbors the Scots, but the English are more culturally similar to the distant Australians and New Zealanders than to their French neighbors. The reason, of course, was the mass immigration of the British to Australia and New Zealand.

But how does one measure cultural distance? One method is to list all the characteristics of every culture and compare them to each other, but this would be extremely time-consuming and very subjective. Inevitably, researchers would disagree as to which characteristics to include and how important each of them is compared to the other.

Genetic sequencing technology gives us a simpler and more objective method: genetic distance. By measuring the aggregated differences in allele frequency on a chromosome, geneticists can measure how similar two peoples are to each other genetically.

In general, the overall amount of difference between two peoples is related to migrations in the distant past. The key assumption is that when two peoples are relatively isolated from each other, they will diverge both genetically and culturally. So the longer that two peoples have lived since their last common ancestor, the more different their cultures are likely to be.

It is important to point out that this method does not assume that genes create a culture and that culture is immutable. Genetic sequencing is merely a convenient method to measure cultural distance, and there is strong reason to believe that genetic distance and cultural distance are closely related.

In an article entitled “The Diffusion of Development” (summary here on my library of online book summaries), Enrico Spolaore and Romain Wacziarg tested how much of an impact cultural distance had on the ability of poor countries to copy wealthier countries both today and in previous centuries. Not surprisingly, they found that geographical distance and cultural distance are closely related. In other words, nations close to each other tend to be culturally similar.

Far more interestingly, they find that cultural distance has a more powerful effect than geographical distance and that nearby nations with significantly different cultures have particularly strong barriers to diffusion. These results help to explain why industrial technologies quickly spread from Britain to the United States and Canada (i.e. between geographically distant but culturally close nations), but much more slowly from Southern Europe to North Africa (i.e. between geographically close but culturally distant nations).

Spolaore and Wacziarg find that after controlling for other possible explanations, cultural distance accounted for 49% of the variation in income differences between 1500 and 1820. Cultural differences played a crucial role in hindering the diffusion of innovation. In 1870, the peak of the Industrial Revolution, the effect increased to 80%. Cultures that were similar to the cultures of the first industrializers were far more willing to copy industrial technologies than those that were more distant culturally.

Fortunately, in more recent years, the barriers of cultural distance have declined (to just under 20%) as a few non-Western nations copied industrial technologies and these could be in turn copied by other nations that were culturally similar. In East Asia Japan played a particularly important role in this regard.

Note that cultural distance is not just a barrier to the diffusion of progress; it is also a local accelerator. If an innovation takes place among one’s group, members of that group are much more likely to adopt that innovation. People tend to copy other people who are like themselves. So culture accelerates diffusion within cultural groups. But given that humanity is divided up into hundreds or thousands of cultural groups, this diffusion within cultures can take us only so far. Overall, culture tends to retard diffusion.

Proximity to the Middle East

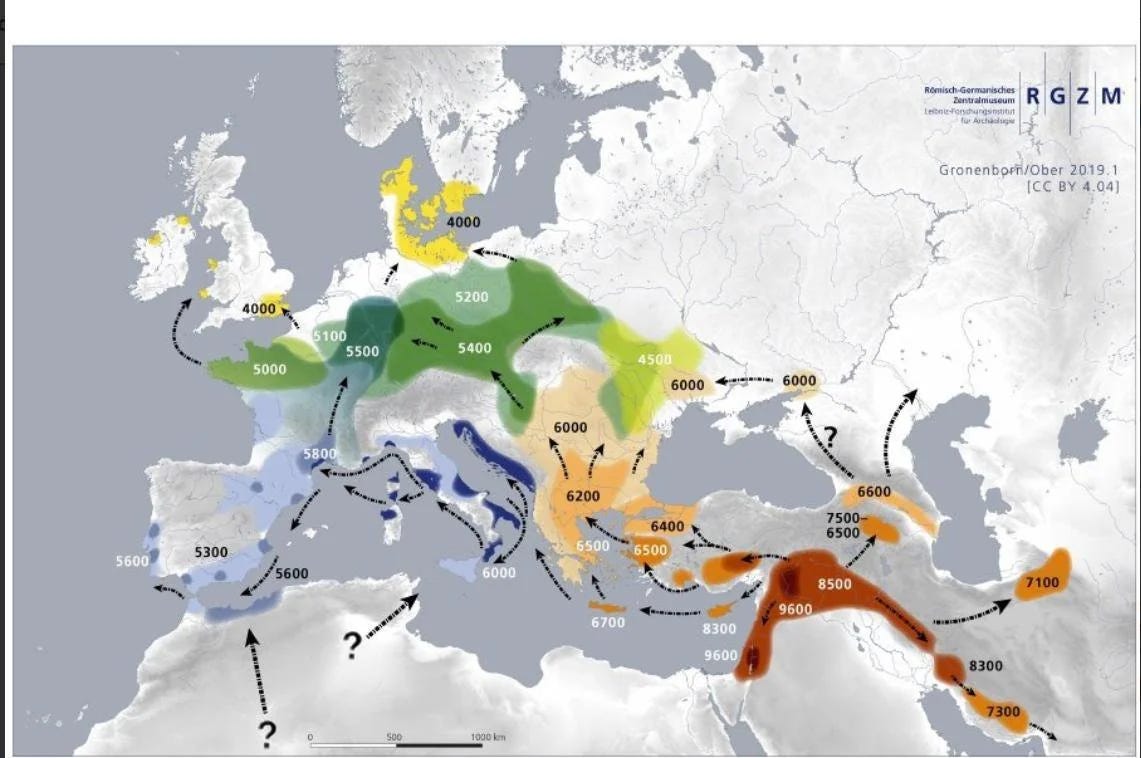

The most important such constraint was proximity to the Middle East. As we have seen, agriculture evolved in the Fertile Crescent (modern-day Syria, Iraq, and Southern Turkey). Early Agrarian societies in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia played an important role early in the Agrarian era. These regions played a critical role because they had many wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals.

As the peoples from those regions migrated westward to Europe (see map above), southward to Egypt, and eastward to Central Asia and South Asia, they brought their domesticated plants and animals with them. Because annual rainfall patterns from the Indus River in modern-day Pakistan and Mediterranean Europe are similar, crops could spread easily.

All of this meant that regions that lacked wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals could receive them via migrants from the Middle East. This enabled regions that were relatively close to the Middle East to overcome the otherwise critical constraint of lacking the wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals.

Societies that were across oceans from the Middle East did not have this advantage. This means that even if a society has physical and biological geographies can fail to develop because it cannot copy crops, technologies, skills, and organizations from the Middle East. This trapped those societies in a state of poverty until Europeans arrived.

Proximity to Steppe Herding Societies

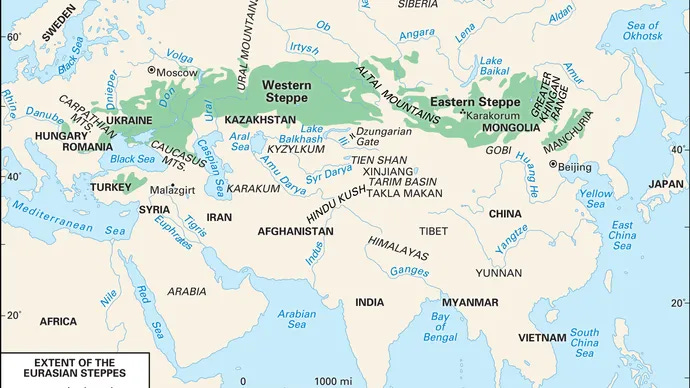

As Peter Turchin has argued (summary here on my online library of book summaries), until the widespread use of firearms and cannons, the horse archers of the Eurasian steppe were the dominant military threat to Agrarian societies. Combining rapid strategic and tactical mobility with standoff weapons in the form of the composite bow-and-arrow, the Herding societies of the steppe were dangerous enemies (I explain society types here).

Peasants in small villages did not stand a chance when even a small group of horse archers chose to attack. And given their propensity to destroy any vestiges of Agrarian society that they came across, one defeat could devastate a village for generations. Agrarian militaries, while very powerful, usually lacked the strategic mobility to intercept horse archers before they could attack.

Agrarian societies that were located near Temperate Grassland biomes in Eurasia with horse archers faced an existential threat. Agrarian societies are a type of society that procures the majority of their calories from plow-based agriculture (I explain biomes here).

The histories of East Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Russia, and the Middle East are full of military conquests by horse archers from the steppe. The first phase of military conquest usually consisted of wholesale slaughter and devastated cities. Usually, the occupiers from Herding societies settled down and placed themselves in charge of the extractive institutions that Agrarian elites had so conveniently already put in place. Over time ethnic tensions between the Herding elite and the Agrarian masses led to the collapse of these regimes, but it often took Agrarian societies generations to recover from the original devastation.

As this perpetual cycle of conquest, devastation, exploitation, liberation, and recovery continued, it had long-term negative effects on economic development. Agrarian elites were forced to extract additional resources from the already over-stretched peasantry to pay for defending the realm.

Sometimes defense spending by Agrarian regimes took the form of bribing nearby Herding societies to not attack. Other times it took the form of building huge defensive walls: the Great Wall of China being the most famous. Other times, it consisted of recruiting rival Herding societies into mercenary armies of horse archers. Whichever strategy Agrarian elites chose, it was never good for economic development.

As Peter Turchin has argued, Agrarian societies in East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Russia were dominated by military competition with the Horse archers of the Central Asia steppe. This forced those Agrarian societies to grow large and ruthlessly extract food surpluses to survive. This centralized extraction stifled innovation.

Agrarian societies of Western Europe and Southeast Asia faced much less of a military threat, so they evolved into more decentralized societies. As we have seen, the political decentralization of Northwestern Europe was a key factor in the rise of Commercial societies and progress.

See also my articles on related posts:

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.