Technology is useless without the skills to use it

We often forget how important skills are to material progress.

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

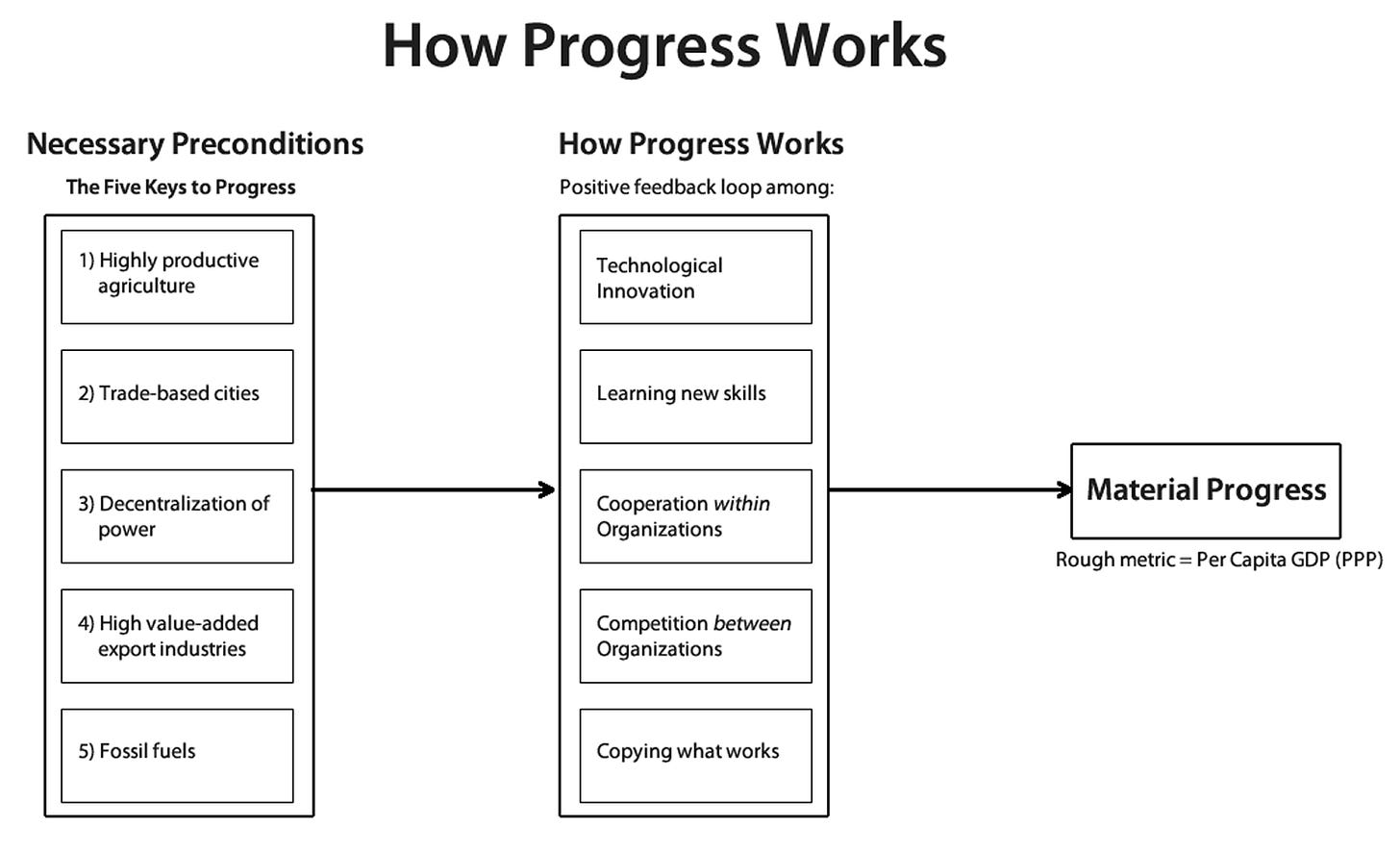

In this series of articles, I explain How Progress Works in greater detail. Once the Five Keys to Progress create the necessary pre-conditions for progress, societies become a vast decentralized problem-solving network that generates progress. So far I have discussed the first factor in how progress works:

Technological innovation. This includes radical innovations such as the railroad, electrical grid, computers, and the internet, as well as the ongoing incremental improvement and differentiation of thousands of other existing technologies.

Today’s topic is the second factor in how progress works: People learning new skills to support those technologies. Without these skills, technologies are not useful, a fact that is often forgotten.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can learn more about How Progress Works with these links:

People learning new skills to support those technologies.

Competition between organizations for scarce resources.

People copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems.

Consumption of vast amounts of useful energy.

Technology Requires Skills

When one thinks about where modern material progress comes from, we often focus on technological innovation. This is not surprising as technological innovation is a key driving force in material progress.

We must never forget, however, that without the proper skills, the most sophisticated technologies are no more useful than a rock on the ground.

While biological organisms can survive and reproduce without human intervention (except for some domesticated plants and animals), technologies cannot exist without human intervention. Technology requires humans to possess highly specialized skills for it to survive and reproduce (by getting widely used by humans).

Even the simplest technology requires some amount of skill to use. In addition, conceiving of the technology, designing it, building it and repairing it are important related skills. Until people possess these skills, a specific piece of technology cannot come into being, or if it does, it would not last very long. It will certainly never spread far enough to become an important part of a society’s technological suite.

Animals as a whole have an enormous variety of “skills” that humans cannot duplicate, but the repertoire of any one species is quite limited. Lions, for example, are very skilled at hunting large mammals along with other members of their pride. A large part of those skills are presumably encoded in their genes, while some come from copying their mother or from practice. But lions and other animals rarely learn a new skill that other members of their species do not possess. Eusocial insects, such as ants, termites and bees, have evolved a specialization that enables a broader repertoire of skills, but even those species are quite limited in their skill set in comparison to humans.

The collective skill set of even the simplest Hunter-Gatherer band, while very simple compared with other types of human societies, dwarfs the skill set of any non-human animal. As a society acquires more complex technologies, its collective skill set increases even more rapidly. This is because each technology requires a host of related skills. The more complex the technology, the greater the number of required skills.

While the total skill set of a society has no upper limit, there is an upper limit on the number of skills that one person can acquire. Learning a skill requires large amounts of time to practice and time is finite.

In his book, Why Information Grows, Cesar Hidalgo (summary here) developed the concept of a “personbyte” to denote the total amount of knowledge and skills that one person can possess. This concept is important because it shows that the only way for a society to increase the number of skills beyond a personbyte is for individuals to specialize in one skill or a small number of related skills. Fortunately, the more a person specializes in a skill, the greater the frequency of the repetitions and the more opportunity to get better at that skill. With an incentive to improve and actionable feedback, humans can become extraordinarily good at one skill.

Skills needed for one technology

The number of skills necessary to maintain just one technology in a modern economy is staggering. To get a glimpse, take a look at an organizational chart of any corporation or a jobs listing website. Among the broad categories of skills relevant to each specific technology are to:

Conceive of the technology (i.e. get an idea for a new product or service)

Design the technology

Test the technology

Build the technology

Market the technology

Sell the technology

Package the technology

Ship the technology

Distribute the technology

Train end-users to use the technology

Finance the technology (enabling customers to acquire the money to purchase the product)

Maintain the technology

Troubleshoot the technology

Repair the technology

Most important of all, the customer/end-user must have the skills to use the technology. And the skills listed above are just broad categories. Within each category are specialized disciplines that are only known to the field.

The vast number of skills in a modern society

To keep track of all the skills in modern society, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has created the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). As of 2018, it consisted of 867 detailed occupations organized into 22 major groups. Even this very large number of occupations is just scratching the surface.

The official category for my profession – User Experience Designer – is “Web Developers and Digital Interface Designers.” In practice, this category consists of dozens of specialties distinct enough that most employers would only look for a person within one of those specialties. And that is only one of 867 official occupations. Even within specialties, a typical worker will specialize in many skills known to only a small handful of employers.

This specialization creates a “Catch-22” situation for technological innovation. Technology cannot come into being and survive for any length of time without all the necessary human skills, but since the technology does not yet exist, neither do those necessary skills.

What this means in practice is that the process for a technology to go from an idea to a fully-realized product being manufactured and sold at scale will often take years or even decades. During this time period, humans must master the dozens of new skills required by the specific piece of technology.

In this way, innovation for an individual technology is a very slow process dominated by trial-and-error learning. But because in modern society there are millions of different types of technologies all evolving simultaneously, the sum total of all innovation is very rapid.

In the next article in this series, I will explain the importance of people cooperating within organizations

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can learn more about How Progress Works with these links:

People learning new skills to support those technologies.

Competition between organizations for scarce resources.

People copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems.

Consumption of vast amounts of useful energy.

Your discussion of skills embodies my concern with the prospects of a shrinking labor force and aging/depopulation that will take place by 2050. If technology requires skills to make them work, what happens when we no longer have enough people with the required skill sets? Does technological advancement stop, or does it regress?

In that note, Robert Bryce has reportedly at length on the shortage of the highly skilled labor needed to build transmission lines. That’s a major reason why a rapid transition to renewables and vast new transmission lines connecting them to the grid isn’t feasible. It’s also why we should either maximizing the existing grid.