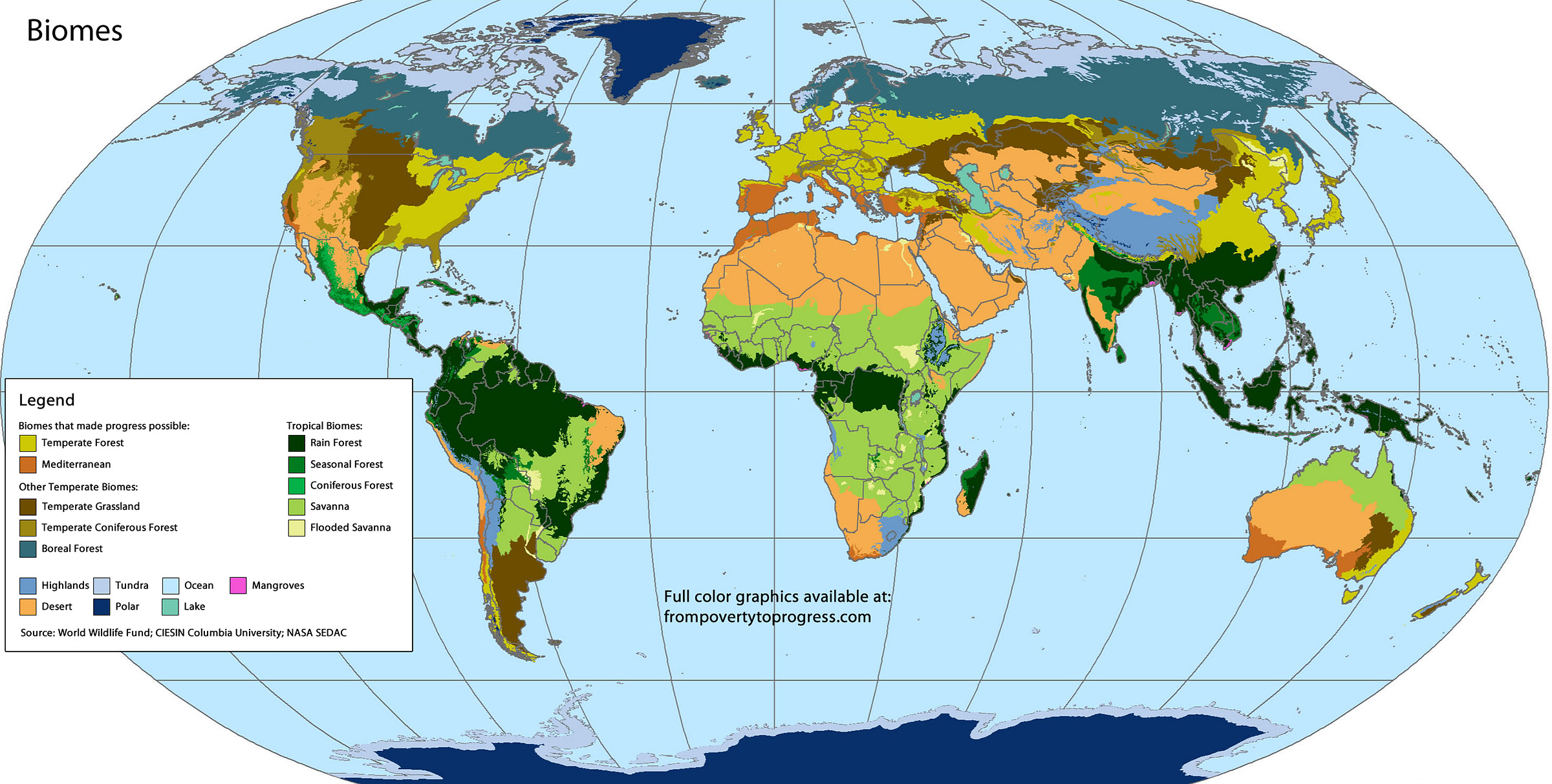

Why Progress Started Where It Did

Or, the most important map that you will ever see.

See also my articles on related posts:

Most of the following is an excerpt from my first book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Biomes That Made Progress Possible

Temperate Forest biome

By far the most conducive biome for the evolution of complex human societies is the Temperate Forest biome. The Temperate Forest biome evolved on temperate latitudes near oceanic currents that carry warm water from tropical latitudes. These warm water currents create the conditions for annual rainfall of over 20 inches per year. The result is a relatively warm, wet climate that is perfect for deciduous trees.

Northern Europe has the single largest Temperate Forest ecoregion, although East Asia and eastern North America also have very large ecoregions of this type. Chile, Australia, and New Zealand each have small Temperate Forest ecoregions. Temperate Forest biomes typically have growing seasons of around six months, with even longer growing seasons in the south.

The powerhouses of the Temperate Forest biome are the leaves on deciduous trees, most of which are species of beech, walnut, ash, maple or birch. While needles on conifers and leaves in tropical latitudes stay on the tree year-round, most deciduous trees in temperate latitudes go through a seasonal cycle of losing their leaves in the autumn and then regrowing them in the spring.

Losing leaves in the autumn protect the branches from cold, dry winters; growing them back in the spring enables trees to deploy what are effectively organic solar panels. Leaves are typically very thin and wide, giving the tree a huge amount of surface area for catching sunshine for photosynthesis. While the trees have evolved this behavior for their survival, the benefits to the rest of the ecosystem are impressive.

Leaves are packed full of sugars and other nutrients, perfect for consumption by insects and browsing mammals. When nitrogen-rich leaves fall to the ground in the autumn and then unfreeze in late winter and early spring, they create a thick layer of hummus on top of the soil. Spring rains wash the nutrients deeper into the soil, where huge numbers of decomposing bacteria and animals ensure these nutrients nourish the deepest layers of soil. The thick hummus also provides a perfect habitat for earthworms and burrowing mammals, which aerate the soil.

During the winter, the trees and many animals in Temperate Forests go into dormancy. Birds usually migrate to warmer climates. The next spring when the snow and ice melt, those nutrients from the leaves are then gathered by plant roots from the soil and redirected into growing new leaves.

Because fresh young leaves contain the most nutrients, spring in Temperate Forest biomes is an explosion of life. Insect larvae hatch to take advantage of this bounty, luring in migratory birds for the feast. Browsing mammals give birth to babies for the same reason. This constant seasonal cycle ensures that Temperate Forests have some of the most productive soils in the world.

In addition, trees themselves give humans one of the most useful materials in the world: wood. Wood can be used for heating during the night and winter, a necessity in colder temperatures. Wood is also one of the most useful materials for the construction of tools, dwellings and transportation devices. Wood can also be used to make charcoal, a crucial first step in metalworking technology.

Humans gradually learned how to use wood, rain and fertile soil to create productive agricultural systems capable of generating a food surplus. This food surplus enabled dense human populations that promote innovation and progress. Countries situated in the Temperate Forest biome include China, Japan, Korea, USA, UK, Netherlands, France, Germany, Russia and Northern Italy. Citizens from societies inhabiting the Temperate Forest biome have recorded the bulk of written human history.

The one key disadvantage of the Temperate Forest biome is the relative lack of native wild ancestors of domesticable plants and animals. Virtually all such species in use today arrived via human migration from other biomes.

Horses, cattle, sheep, goats and pigs all originated in Temperate Grassland biomes in Asia. For this reason, to have a big impact on human history, the first successful societies located in Temperate Forest biomes were in Eurasia.

Geographical isolation from Eurasia is the key reason why it took so long for complex societies to evolve in Temperate Forest biomes of North America, Chile, Australia and New Zealand. These regions lacked domesticable animals, and they were not near regions that possessed them. The arrival of immigrants from complex societies in Europe triggered some of the fastest societal changes in human history because this missing ingredient suddenly arrived.

Mediterranean biome

The other biome that is capable of supporting vast expanses of productive agricultural systems is the Mediterranean biome. The Mediterranean biome evolves on the western side of continents between the latitudes of 30 and 40. Its key distinguishing characteristics are rainy winters and a long, hot and dry summer. This rare combination creates a short growing season when temperatures are mild and the soil is moist.

Not surprisingly, given its name, the bulk of the Mediterranean biome is located along the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, North Africa and the Levant. Smaller and more isolated Mediterranean ecoregions can be found in Chile, California, South Africa and Australia.

The Mediterranean biome is for all practical purposes a desert for nine months out of the year. For this reason, most of the plants have evolved to conserve water through the long dry season. Most plants are evergreens with thick leathery leaves, and many of them protect themselves from herbivores with aromatic oils that humans use in cooking Mediterranean cuisine.

While not as conducive to the evolution of complex societies as is the Temperate Forest biome, the Mediterranean biome has supported many civilizations, particularly Ancient Greece, Carthage and Rome. Its primary disadvantage is the lack of an annual leaf fall, so the soil tends to be much less productive. And fewer trees mean that wood is not as plentiful.

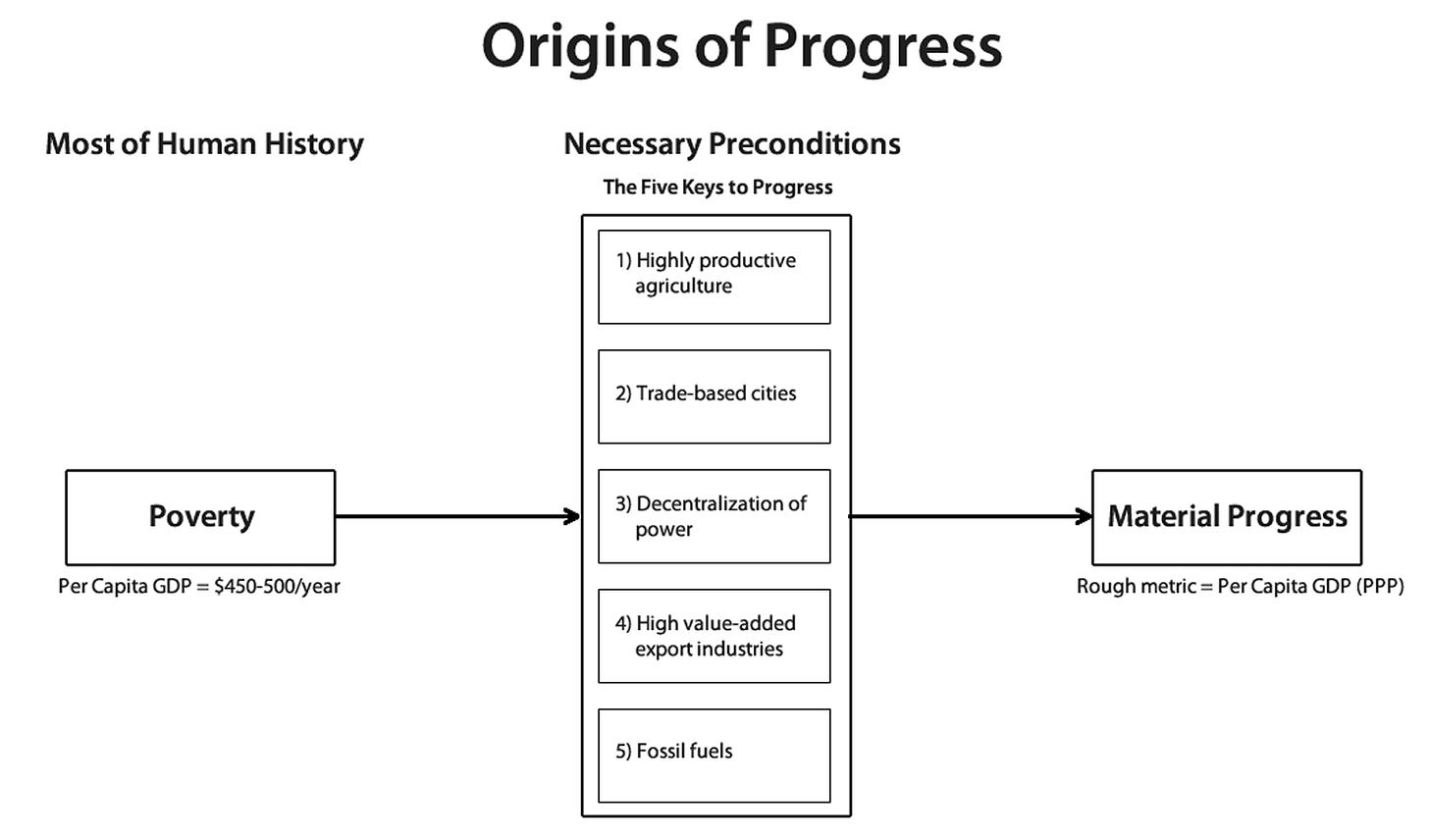

So we can see that biomes placed enormous restrictions on the types of human societies that could evolve. Most biomes are simply incapable of supporting vast expanses of productive agriculture, the first of the Five Keys to Progress. Some biomes are only capable of doing so where there are rivers, a very small portion of their landmass.

Even today, with all our modern technology, agricultural regions that produce large amounts of staple crops, such as wheat, rice, corn, or potatoes, is highly restricted geographically. Traditional societies without these modern technologies were even more constrained by geography.

The geographical constraints lowered the food surplus, which meant that almost all of society had to focus on producing food. This, in turn, meant that few other people were left to solve other problems. Only a small political, religious, and military elite in capital cities thrived due to extracting rent and taxes from the peasantry.

Only the Temperate Forest and Mediterranean biomes are capable of supporting vast expanses of productive agriculture using pre-Industrial technology. Those exceptions tended to be either on river deltas (where the plant nutrients were carried by rivers rather than being in the soil) or very localized regions with fertile volcanic soil. None of these exceptions experienced material progress for the masses before the late 20th Century. And many regions with a Temperate Forest or Mediterranean biome lack domesticable animals that make plow-based agriculture possible.

My next post on the constraints that geography has had on human material progress discusses the impact of rivers, altitude, soil, and growing seasons.

See also my articles on related posts:

Most of the above is an excerpt from my first book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Regarding the beginning of progress in 1200, there is a substantial literature on economic “efflorescence”, and Joshia Ober documents the case of Ancient Greece:

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691140919/the-rise-and-fall-of-classical-greece

Modern estimates suggest that Classical Greece had a real income similar to that of 1920 Greece...

While I agree on the general thesis of biomes hugely influencing what kind of societies are possible, I believe you may be oversimplifying a few things, or perhaps that your claim is a bit too absolute.

Curiously, all the earliest civilizations did not in fact arise in these climate zones, save one or two. If we look at the earliest agrarian societies, or societies that independently developed writing, only Han Chinese heartland and parts of ancient Persia are the temperate zone.

Instead, the earliest civilizations arose in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, the Indus river valley (India-Pakistan border area), the Andes mountains (Incas and their pre-cursors), Central America (Olmec and Maya), the valley of Mexico (Aztecs and their pre-cursors).

Furthermore, once complex societies started getting underway, most of them were not in the temperate zone. If the temperate zone were the natural birthplace of Progress, then why was it only in the 1400s/1500s that (outside of China and Iran), these regions (Flanders, Netherlands, East England) started developing faster?

Indeed, when the early European colonizers travelled across the world, they often found societies that were more complex than their own. E.g. the Spanish who first entered Tenochtitlan concluded that in many aspects it was more advanced than their own society.

The same goes for the Asian societies they encountered. We also don't see sites like the Angkor Wat, the Borobudur or the Maya temples in European/North American temperate regions.

Also, compared to the Austronesians who settled areas as far flung as New Zealand, Hawaii, Magadascar and Easter Island, the West Europeans were quite late with ocean travel.

To say that only "Temperate Forest and Mediterranean biomes are capable of supporting vast expanses of productive agriculture" I think isn't quite accurate. The Central Mexico Valley, the Maya regions, the Andean cultures, ancient India and Sri Lanka, the Khmer civilization - these are just a few of the regions outside of these biomes that did in fact support vast expanses of productive agriculture, with civilizations more complex than their contemporary counterparts in Western Europe or North America at the time.

Again, I agree with the approach by looking at biomes, but I think the argument needs a bit more nuance.