Humans organize like no other species

Social organizations are part of the "Secret of Our Success"

One of the key foundations of complex societies is humans’ ability to cooperate in large, complex, and ever-changing groups. As Joseph Henrich argued in his excellent book, The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter,

The secret of human success has been our ability to form collective brains that store far greater amounts of information and skills than one person can possibly understand.

Humans are a cultural species and that characteristic is firmly rooted in our genes

Culture and genes work together in an evolutionary process that is unique to humanity and is the root cause of changes and innovation.

You can read a summary of his book at my online library of book summaries on technology, history, economic growth, and progress.

This is a stark contrast to most of the animal kingdom. When one looks at the animal kingdom overall, one can group each species into:

Solitary animals

Social animals

The vast majority of animal species interact little with each other, except for brief encounters for the sake of sexual reproduction or mothers rearing their young. Most other interactions between members of the same species lead to violence.

Herding animals

Among social animals, the most common type of social organization is the herd. Many birds, fish, and herbivorous mammals live in large groups for protection from predators. Herds reduce the likelihood that a predator will find prey, and even when predators do so, herding increases the chances that the predator will target a different animal within the herd.

Though the herding animals are geographically concentrated, there is very little cooperation within the group. Rather than truly cooperating, each animal within the herd has an instinct to:

Stay close to the group

Avoid a predator

Each animal is effectively “hiding behind the other members of the herd.”

Social Predators

While most predators are solitary, some species of carnivores live in social groups. Social predators tend to engage in much higher levels of cooperation than herding animals. Social predators typically hunt larger prey than solitary predators. Social predators include lions, wolves, dolphins, and hyenas.

Social predators, animals tend to be very intelligent and cooperative, but there is little variation in roles within the group other than those based upon gender and status within the group. A pride of lions in one location is very similar to a different pride of lions in another location.

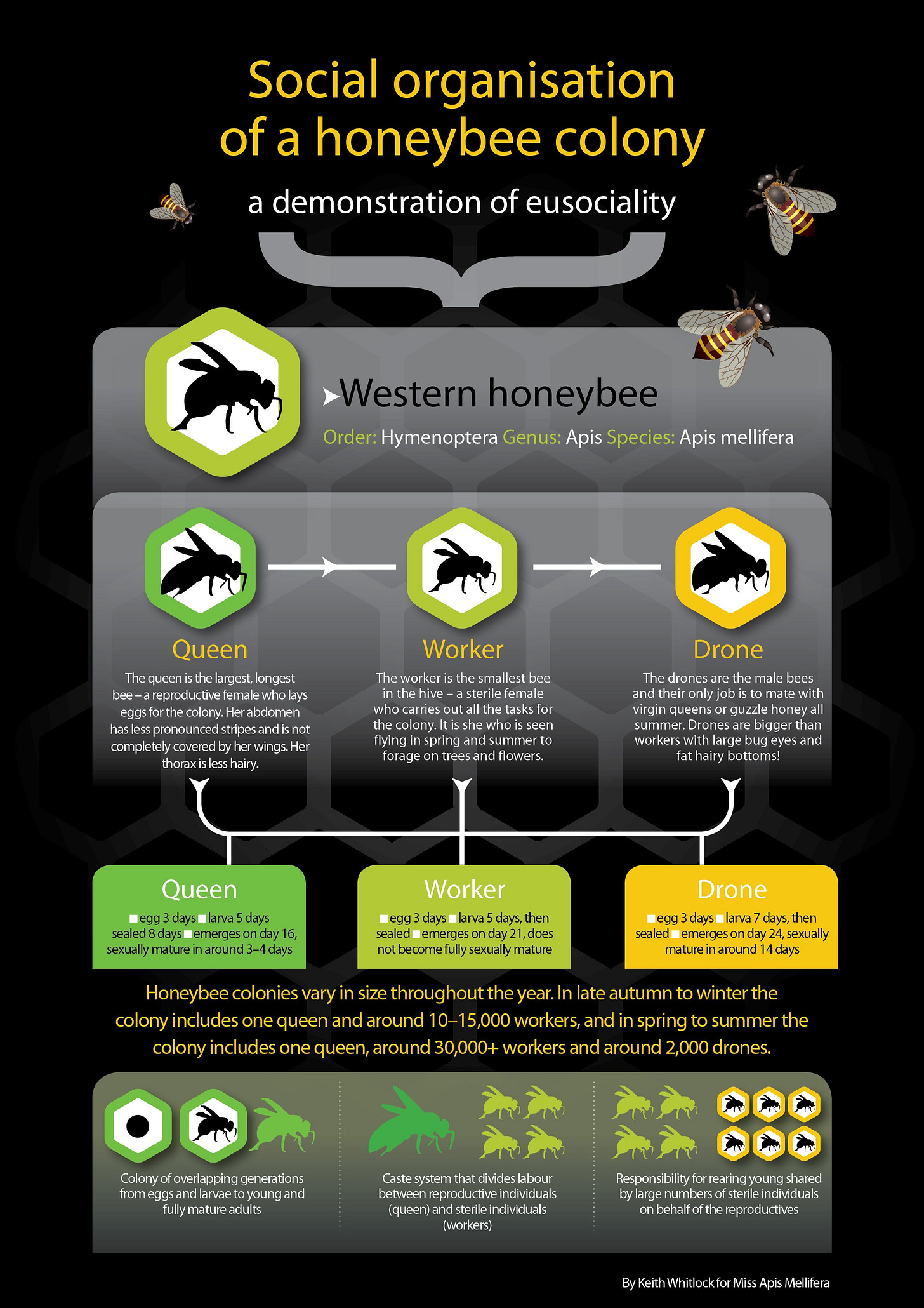

Eusocial animals

Perhaps the highest form of non-human social organization are eusocial animals. These include most bees, ants, wasps, termites and a few other rare species, such as the naked mole rat. Each member of the colony is closely related genetically (typically from one queen), and the colony is divided into castes. The close genetic relations between all the individuals within the colony enable them to behave as one super-organism.

Each caste is composed of individuals with their own unique skills and behavior: a primitive division of labor. The behavior of each individual within the caste is very simple, but because the populations of the colony are very large and the castes are specialized, the colony as a whole exhibits very complex behavior. Eusocial insects are marvelous examples of how very high levels of complexity can derive from very simple patterns of behavior.

Human social organization is unique

Despite the wide variety of social organizations within the animal kingdom, they all pale in comparison to human social organizations. Note: going forward I will use the term “animal” to denote all non-human animals, even though humans are obviously animals.

Among the biggest differences between human social organizations and the rest of the animal kingdom:

Animal social organizations are generally composed of individuals that are genetically related to each other. Most human social organizations are composed of individual humans that are not genetically related to each other.

Animal social organizations are generally composed of individual animals that only differ based on gender. Each individual within the human social organization, however, has highly specialized roles. As the group becomes larger in size and more densely populated, those roles become more specialized.

Roles within human organization are dictated by cultural and individual choice, not genetics (although the sexual division of labor is a key exception).

Animal social organizations within the same species tend to be roughly the same size. Human social organizations, however, are highly varied in their size. Some human social organizations consist of a few dozen members, while other human social organizations have populations that reach into the millions.

Animal social organizations within the same species tend to have roughly the same population density across geographical areas. The primary variation is due to the availability of food. The population density of the human social organizations varies greatly. Some human social organizations have population densities that are less than social predators, while other areas have population densities that rival eusocial colonies.

Animal social organizations within the same species tend to look very similar. Human social organizations tend to differ from each other in dress, language, religion, and other characteristics (culture). Indeed, these variations are deliberate signals separating “us” versus “them.”

Animal social organizations within the same species tend to inhabit very similar natural environments. Human social organizations, however, have evolved to live in very different natural environments. In other animals, moving into new natural environments usually leads to the evolution of different species. Technology enables humans to adapt to a far broader range of environments.

Animals tend to have behaviors directly derived from their genetics, so it is hard for most of them to learn new skills. Human individuals have the ability to create new behavior (skills) by doing them repeatedly and modifying their behavior based upon the results.

Many animals have the ability to copy, but copying typically comes from copying their mother. Individuals have the ability to copy the behavior of others, so anything once invented is not forgotten by future generations.

Individual animals can only be a member of one social organization. Humans in many societies can be members of multiple social organizations at the same time:

Families

Employing organizations

Labor unions

Nations

Religions

Social clubs

Charitable organizations

Political parties

Human social organizations tend to generate world views, such as religion or ideology, that:

Determine what is moral and immoral

Explain the unexplainable

Give meaning to people’s lives

Create a shared identity with others.

Project an image of morality to others within their group to ease cooperation via:

Dress, jewelry, hairstyle

Mannerism

Rituals

Terminology

These world views can cause human social organizations to undertake tasks that would not otherwise be rational for the individual human. Some of those accomplishments are highly beneficial for the organization (and indirectly for the individual), but some lead to suicidal results.

Key to building a unique type of social organization is the invention of culture (the transmission of information via non-genetic pathways). Culture enables groups of humans to adapt much faster to changing natural and social environments. And while human social organizations adapt, they change and differentiate the culture itself. In certain circumstances, this can lead to runaway change that is impossible in other species.

Changing social organizations over time

One of the most fascinating phenomena is how much human social organizations change over time. Like all species, human organizations must adapt to the constraints in the natural environment. The most important constraint is the amount of edible food in a specific geography. Unlike other animals, humans can innovate and copy subsistence technologies that enable us to create far more food calories per square mile than would otherwise be present. When we do so, humans can form entirely new types of social organizations that have never existed before. No other animal can do anything like this.

The best concept to understand this change over time is the Society Type. A society type is a category for how a society organizes itself to transform energy and other natural resources into food and other useful technologies. This is most easily measured by how people acquire a majority of their calories. If, as they say, “you are what you eat”, then the society type concept emphasizes that “we are how we acquire what we eat.”

When viewed from the highest level, there are only a small number of means through which a society can acquire enough calories to survive and reproduce. The following is a list of society types and how they acquire the majority of their calories:

Hunter-Gatherer societies: Hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants.

Fishing societies: Fishing, hunting sea mammals, and gathering shellfish.

Horticultural societies: Farming domesticated plants (using hand tools) and sometimes also raising domesticated animals.

Agrarian societies: Farming domesticated plants (using animal-driven iron plows) and raising domesticated animals.

Herding societies: Herding domesticated animals on the wild range.

Commercial societies: Selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the market (but with limited use of fossil fuels).

Industrial societies: Selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the market, and widespread use of fossil fuels.

Each of these distinct Society Types has a unique spectrum of:

population size

population density

political structure

economic structure

rates of innovation, and

many other characteristics

One can understand how these social organizations changed over time in the following graphic:

I did not recall if I had also already mentioned Michael Tomasello's ideas about humans being the ultrasocial animal, so I went to your Ratchet of Technology web page searching for Tomasello and found your notes on his book Why We Cooperate. From the book's text that you displayed, he was discussing the concept of cooperation as partly driven by genetically acquired characteristics exhibited by young children, and their later response to shaming or social pressures to confrom to the norms of their group.

But this social drive to conformity would be somewhat at odds with our current views on personal liberty, and on the space or respect that we now give to innovators to achive those things leading to our progress (material and otherwise). This might suggest that part of your path to progress was related to establishing those cultural norms that did not fully reject innovation and learning from "other groups". Perhaps some groups failed to advance because they adopted "bad" cultures, for whatever reason they thought them otherwise merited. For example, the strong religious emphasis during the "Dark" and "Middle" ages did not totally stop selected technological advances (in agriculture in particular) but did appear to restrict them to selected areas not at odds with Church doctrine.

When I read this in the eusocial segment, "The close genetic relations between all the individuals within the colony enable them to behave as one super-organism", I had the image that perhaps the human brain could be thought of as a "mental hive" of sorts. But I understand there are at least 100 to 200 different types of neurons, vs. perhaps 3 to 8(?) caste types in insect colonies. Of course the number of brain cells and the number of synaptic connections far exceeds the population of even the largest termite hive. Thus humans are able to support many fold increases in complexity, part of your analysis and equation for achieving progress. Conversely, I gather there are only a few types of biochemical reactions occurring during the excitation of nerve cells and the transfers of signals across synapses. Do you know if anyone has explored this analogy of our brains or culture?