Understanding the Chinese economic miracle

No matter how big of a deal we think it is, it is actually bigger

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

The rise of China to become an industrial, political, and military superpower is by far the most important trend of the last 30 years. The only rival trend during that period was the enormous increase in the material standard of living for most of the world. And China played a substantial role in that trend as well.

China experienced a startling transformation in just one generation. That transformation was in some ways unique in world history, but it is often taken for granted.

In 1990, China had a per capita GDP that was below Sub-Saharan Africa. And that had roughly been the same material standard of living for the Chinese people for 4500 years (or roughly 225 generations). Then within one generation, it all changed.

Let those three facts sink in for a moment.

And no one could have seen it coming.

In 1976 after almost 30 years of rule over the most populous nation in the world, Chairman Mao died. The Cultural Revolution, Mao’s attempt to purge the Communist Party of all “Rightist” opposition, left Chinese society in shambles. In many ways, the Chinese people were worse off than in:

1931 (when Japan invaded Manchuria), and even

It had been a very rough 65 years for the Chinese people. Violence, war, instability, repression, and poverty seemed to be their fate.

After a two-year power struggle between the Maoist “Gang of Four” and reformists, Mao’s arch-frenemy, Deng Xiaoping, and his Eight Elders (or was it the Seven Dwarfs?) consolidated power. These geriatrics ruled China behind the scenes through the Central Advisory Commission, which appointed members to the ruling Politburo.

The fact that Deng Xiaoping was even alive was quite an achievement in itself, as he repeatedly tried to moderate the volatile and brutal Mao Zedong for 30 years. While many others were purged from the party (or worse) during the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping managed to remain on the edges of power after brief forced “retirements.”

Deng and the Eight Elders implemented what they called “Socialism with Chinese characteristics”, which was very undefined at first but gradually evolved into a powerful industrialization strategy. I seriously doubt that the Eight Elders had any idea how to run an economy, but they knew that:

Communist economics does not work.

Western-style politics will not work in China.

The Chinese people needed to be controlled by one party to avoid the frequent civil wars in Chinese history. Chinese history is dominated by a repeated cycle of Dynasty > Collapse > Civil War > New Dynasty > Repeat for Millenia…

Above all other goals, China needed to get richer.

China could only get richer by:

Leveraging the global trade system established and protected by the United States.

Copying Western technologies, skills, organizations, and acquiring direct investment.

Decades of hard and smart work by the Chinese people.

It is not clear when the Eight Elders settled into a well-thought-out industrialization strategy, but it likely happened sometime in the early 1990s. Notice the huge uptick in Foreign Direct Investment in that period.

This Foreign Direct Investment was combined with a steady retreat of the Chinese government from its Communist economic policies that controlled the economy. It was only in 2006 that China began to implement what we now call “industrial policy.” But I think it is a mistake to claim that because China did not have an industrial policy, they did not have an overall government industrialization strategy.

So how did China do it?

This is a complicated question with many causes, and I do not pretend to be an expert in China. But I do think that I can summarize a few key causes.

Chinese industrialization strategy can be summed up in one phrase:

Debt-financed investments in infrastructure and export manufacturing and copying the technologies, skills, and organizations that it took the West centuries to innovate and deploy at scale. This is China’s means to achieve the fourth Key to Progress: high-value-added industry that exports to the rest of the world as quickly as possible.

Not many people realize just how much debt plays a role in the Chinese economy. At a minimum, China’s national debt is $10 trillion. Most likely, it is at least 3-4 times that amount. Even if the first figure is the correct one, this debt amounts to 66% of GDP and $7000 per citizen. Interest payments for central government bonds and municipal bonds are $280 billion per year.

Here is a more realistic Western estimate of China’s actual debt load and composition:

This debt is a massive cost for the Chinese people, one that may well come back to haunt them in the next few decades, but even those debt levels are clearly better than another 65 years of poverty and instability.

What is the Chinese industrialization strategy?

More specifically, the Chinese industrialization strategy goes something like this:

The central government (or more accurately the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party) determines a few favored sectors to receive debt financing for the coming years. All other sectors are on their own.

In general, those sectors are chosen based on a long-term strategy to:Use the following global comparative advantages to lure Western companies to invest in domestic manufacturing plants:

Cheap labor (the most important factor before 2010)

Manufacturing of vast scale, flexibility, and speed (the most important factor after 2010)

The promise of access to the Chinese domestic market (which never seemed to materialize).

Copy what the Westerners do, but with cheaper labor and Chinese debt-financed capital. This enables China to quickly copy all the technologies, skills, and organizations that it took the West centuries to innovate and deploy at scale.

Copying is the “cheat code” of industrialization. Copy what works in richer nations is an essential part of How Progress Works.

The copying by China has been done using many methods, including:Insisting foreign companies set up local-joint ventures on Chinese soil to gain access to Chinese labor and markets.

Reverse-engineering products made in the West, Japan, and South Korea.

Paying foreign experts for technical advice.

Acquiring foreign companies.

Sending Chinese students to overseas universities to learn technical skills.

Espionage at home and abroad.

Gradually ratchet up the value chain toward higher value-added export products. Leverage the necessary technologies, skills, organizations, and capital from existing industries to learn the skills needed for the new industry and use the advantage of cheaper labor to outcompete richer nations.

Build the infrastructure needed for a modern urban society so workers can relocate to the major urban areas where the factories are located. The workers do not need to be comfortable or happy, but they do need to be productive and unwilling to revolt against the Party. This is China’s means to achieve the second Key to Progress: Trade-based cities.

Vertically integrate entire supply chains within China so as not to become dependent on foreign imports. Once the Chinese learn how to implement one step in the supply chain for an industry, they leverage those technologies, skills, and organizations into the next step in the supply chain. They continue this process until they dominate the entire supply chain within that industry.

Checkmate.

Favored Sectors

In the past, the Politburo’s favored sectors are listed below (roughly in chronological order). Notice how the industries gradually become more profitable and complex:

Agriculture, the first Key to Progress (more on why here)

Textiles for export (a common entry point for nations to get into manufacturing exports, including pre-industrial Commercial societies)

Consumer electronics for export (just like Japan and the Asian Tigers did in previous generations)

Light manufacturing for export (ditto above)

Metal production (iron, aluminum, steel, copper, and many more) for domestic infrastructure and exports

Coal-burning power plants and the electrical grid

Other urban utilities, such as heating, water, sanitation, and internet cabling

Highways and roads

High-speed rail

Real estate, particularly high-rise apartments and condominiums

Heavy machinery for domestic construction and export

Ship-building for the transportation of exported goods and naval ships

Mobile devices for domestic consumption and export

Mineral refining for domestic construction and export

Medical equipment

Batteries for domestic manufacturing and export

Integrated circuits and microchips for domestic manufacturing for export

Electric vehicles for domestic sale and export

Artificial intelligence

Implementing the strategy

This overall Chinese strategy listed above is implemented in the following manner:

The Politburo sets goals and timetables for local governments to achieve within those favored sectors.

Since local governments have no independent taxing authority, so they have no choice but to follow the central government’s plan.

The local governments compete against each other to see who can most quickly achieve those goals.

Local governments acquire the capital for these investment projects by selling land (which they monopolized by Chinese law) and issuing bonds, while private companies borrow at subsidized rates from government-owned banks.

Private and government organizations plow the debt financing into investments in infrastructure and export manufacturing.

The number of private companies in the favored sector explodes in both number and size, but gradually the less effective competitors are weeded out and go bankrupt. Only the most competitive private firms survive (although political favoritism also helps quite a bit).

Leaders of the local government who perform best are promoted up in rank within the party and to a higher level of government. Leaders of the local government who perform worst see their careers stall or worse. This is a Chinese form of Merit in the public sector.

The owners of the private companies that succeed become billionaires and members of the Communist party. This is a Chinese form of Merit in the private sector.

The Chinese economy booms, particularly in the favored sector.

The Chinese people and the rest of the world marvel at the results (and rightfully so).

Eventually, over-production relative to demand in that sector becomes so acute that the entire sector goes bust, and it is impossible to make money. A new wave of private companies goes bust.

Eventually, the Politburo realizes that it has gone too far, so it finds a new sector of the economy to flood with debt-financed investments.

The cycle repeats…

Communism that Works

If you ignore the debt problem and the lack of individual freedom, this is a masterful system. One might call it “Communism That Works.”

Like the Soviet Union and other Communist regimes, China has centralized planning. This is in line with Marxist thinking that central planning is more efficient than capitalist markets.

In most ways, however, China is very different from other Communist regimes.

Almost every product has a free-floating price.

This is the most important difference, as prices send signals about the relative scarcity of an item and create incentives for private actors to rectify those scarcities. In the Soviet economy, the government set all prices, so in the long run, the economic system was guaranteed to fail. No planner could possibly get all the correct information about which products were needed and which were being over-supplied.Exporting to the wealthy Western nations (and later everyone else) is central to the Chinese strategy.

This is the second key difference as being forced to export creates a price and quality discipline that domestic demand in a poor economy cannot achieve. The wealth created by high-value-added export industries can then be spent locally by its employees, generating demand for a gaggle of smaller local businesses. This wealth also creates a steady revenue stream for governments to invest in education, health, transportation, sanitation, and energy infrastructure.

Except for oil, natural gas, and minerals, Communist nations during the Cold War exported very few products. Communist industries just had to satisfy the planning goals. They did not have to compete against Western corporations internationally. This led to very high levels of inefficiency.Privately-owned industry plays a key role (as do government-owned enterprises), and those privately-owned companies ruthlessly compete against each other.

Because of the above, central government planning reacts relatively quickly to economic realities, and planners are willing to pivot to different sectors.

In comparison to the Communist governments during the Cold War and wealthy Western nations today, there is relatively little welfare state. Chinese citizens are expected to relocate to growing cities, work hard until 60ish, and spend relatively little money.

(Until recently) The government focused few financial resources on the military. This is exactly the opposite of the Soviet Union, where the military was the most favored sector of the economy.

To illustrate how successful this strategy has been, let’s use graphics from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (which by the way is a fabulous website). Here are Chinese exports in 1995 (the oldest year in their database).

Note that this data excludes services, which were likely minimal in that year, and it is only exports, not domestic sales.

Each color is a sector of the Chinese export economy. The two biggest categories in 1995 are Textiles (green) and Machines (blue). If you want a clickable interaction, you can find it at the link above. Just click “Historical data” at the top and enter “1995” in the “Year” field.

Now let’s take a look at 2022 data (the most recent year in their database).

First, let us pay respect to the total exports listed at the top of each graphic: $3.73 trillion in 2022 vs $195 billion in 1995!

That is 20X growth in 27 years! <insert head exploding emoji here>

Of course, some of “growth” is actually inflation, but this is still a phenomenal increase.

I am pretty confident in saying that this is the most radical absolute growth in export manufacturing in world history, and I seriously doubt that any previous nation comes even close. There are still plenty of Chinese citizens alive today who remember the death of Chairman Mao in 1976.

My great-grandmother was born in the 1890s, and she died in the late 1980s. She went West in a covered wagon on the Oregon Trail as a child and lived to almost the Internet era. The change that she saw in her lifetime was mind-boggling. And that is less change than a typical Chinese retiree today experienced in their lifetime.

Now let’s take a look at the destination of those exports by nation in the same years. The first graphic is from 1995.

And here are the destination nations of Chinese exports in 2022.

Two regions stand out, particularly in 1995.

Japan and the Four Asian Tigers make up 48.77% of exports in 1995 and 23.57% in 2022. My guess is that if we had earlier data, this East Asian focus would be even more intense. While the percentage of exports declined, the overall amount of exports grew so fast that China became the hub of East Asian manufacturing.

It makes sense to start with neighboring East Asian countries that are already experiencing economic growth. And those East Asian nations built that growth by exporting to the United States and other wealthy Western nations, so when viewed at a very high level, China copied the five other East Asian nations.

The United States made up 19.2% of exports in 1995 and 14.8% in 2022. That also makes sense, as the United States is the largest consumer market in the world. While the percentages of total exports actually declines, given the 20X growth, it still transformed many American industries, particularly retail sales and manufacturing.

It is also important to point out that Chinese exports grew rapidly in the rest of the world, particularly Europe and the rest of Asia. Today virtually no nation is untouched by significant amounts of Chinese exports. China is no longer just the hub of Asian manufacturing. China is now the hub of world manufacturing.

Economic Complexity

The Economic Complexity Index (ECI) measures the complexity of the technologies, skills, and organizations of the export from a given economy. In general, low complexity economies export one or a very small number of simpler products, such as agriculture, minerals, oil, or natural gas. High-complexity economies export a wide variety of high value-added machinery.

The best way to learn about economic complexity is by reading summaries from my online library of book summaries. The best place to start is with the “Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity” by Hausmann, Hidalgo et al

ECI is purported to be more accurate predictor of GDP per capita growth than traditional measures of:

governance

competitiveness and

human capital.

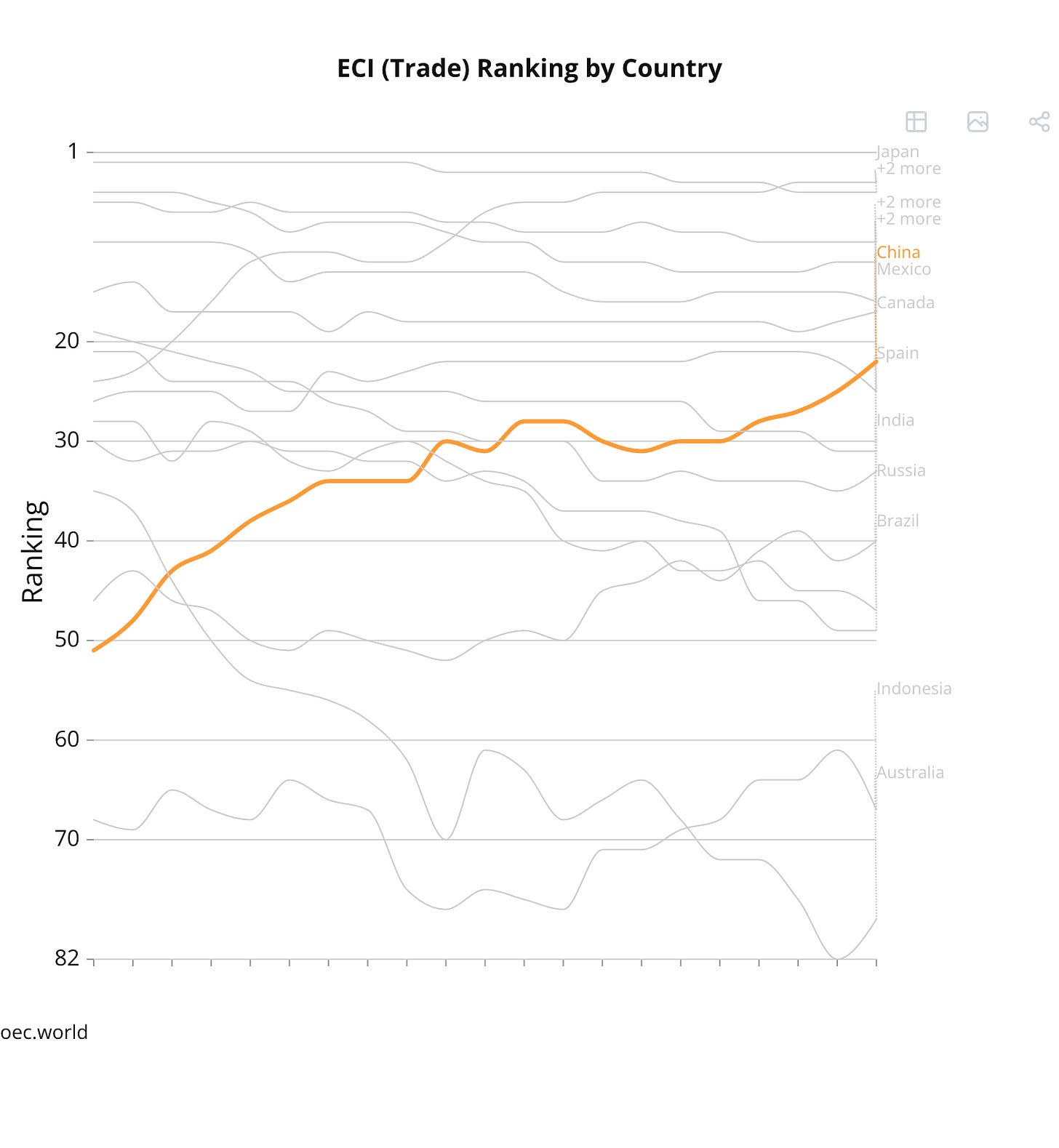

If we look at the national ranking of Economic Complexity Index from 2002 to 2022 on the OEC website, we can see the dramatic transformation of China (and a few other nations). China went from -0.042 and 51st rank in the world in 2002 to 1.12 and 22nd rank in 2022. For a nation of over 1 billion people, this is a very impressive achievement. The only other nation with a comparative transformation is South Korea (from 23rd rank to 4th).

Here is a list of the nations that were in the Top 25 in 2022 and have risen at least 10 spots in ranking since 1998 ranked by their upward movement on the ranking (sorry to keep changing the years, but I have to go with what data is available):

China rose from 59th to 22nd, rising 37 ranks (what a surprise!)

Hong Kong rose from 58th to 21st, rising 37 ranks (Hong Kong is now part of China)

Thailand rose from 63rd to 29th, rising 34 ranks

Malaysia rose from 54th to 24th, rising 30 ranks

Taiwan rose from 29th to 3rd, rising 26 ranks

South Korea rose from 32nd to 4th, rising 29 ranks

Singapore rose from 26th to 6th, rising 20 ranks

Romania rose from 44th to 26th, rising 18 ranks

Lithuania rose from 45th to 30th, rising 15 ranks

Hungary rose from 28th to 14th, rising 14 ranks

Czechia rose from 17th to 7th, rising 10 ranks

Japan rose from 4th to 1st, rising 3 ranks.

The list is dominated by East Asian nations, with a few Eastern European nations sprinkled in at the bottom (an impressive achievement nonetheless). With the exception of Japan, Switzerland, Austria, Czechia, and Slovenia, every nation in the Top 20 in Economic Complexity in 1998 dropped in ranking. Many European nations completely dropped out of the Top 20 by 2022.

So, for all of these negative consequences, the Chinese industrialization strategy have been successful at transforming the Chinese economy and making it the manufacturing hub in the world.

But can it be duplicated in other nations?

I will try to answer that question in future articles.

Fantastic article.

I would note that between the 1980s until a few years a ago, China was very politically and economically decentralized, it even had partial local capital market fragmentations and the ability for local governments to engage in economic policy and even have local trade frictions, and it had very strong local parties with most policy action happening at lower levels and wide latitude for policy variability. All of that its quite similar to how the USA was for the first 200 years of its existence!

But Xi and the powerful special interest groups around him at the national center have been working overtime to try and change this and in recent years they've made headway... lets hope they are defeated!