Understanding how progress works

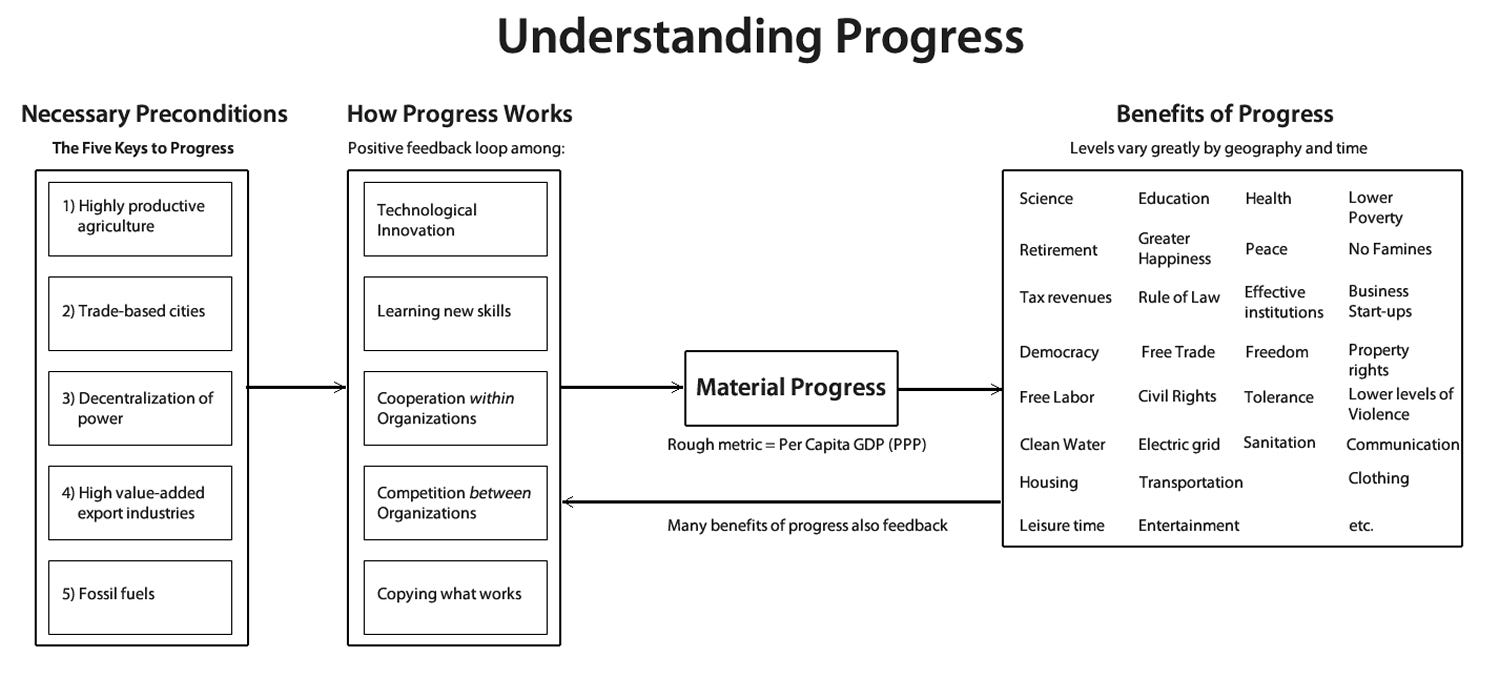

Once the Five Keys to Progress are established, the specific mechanisms of How Progress Works come into play.

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

In my previous excerpt, I made the case that the Five Keys to Progress is an essential unifying concept for understanding progress. They are critical because they are the necessary preconditions for a society changing from a state of poverty to a state of progress, and they are actionable in today’s world. In other words, the concept not only helps to understand the world but also how to make it better.

Once a society acquires the Five Keys to Progress, that society can transform itself into a vast, decentralized problem-solving network. Instead of people competing against each other for scarce resources such as food, status, and land, individuals can focus on solving each other’s problems at scale by cooperation through market exchange.

The Five Keys to Progress enable us to cut through all the clutter of history and modern times so that we can focus on what really matters. They enable us to answer some of history’s most difficult questions, as well as providing policy solutions and practices that can work.

How Progress Works

The question naturally arises: how does this vast, decentralized problem-solving network function? What are the principle mechanics that enable this network to deliver progress both today and in the past?

In this excerpt, I explain How Progress Works. I will focus on the lower-level mechanics of that vast, decentralized problem-solving network. A good way to think of it is that once the Five Keys to Progress create a critical mass for preconditions for the network to emerge, these lower-level factors are what enable the network to produce progress.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Under the right conditions (i.e. the presence of the Five Keys to Progress), societies become a vast decentralized problem-solving network that generates progress. The network creates progress from a positive feedback loop among the following:

Technological innovation. This includes radical innovations such as the railroad, electrical grid, computers, and the internet, as well as the ongoing incremental improvement and differentiation of thousands of other existing technologies.

People learning new skills to support those technologies. Without these skills, technologies are not useful, a fact that is often forgotten.

People cooperating within organizations. Those people work together using a wide variety of skills and technologies to accomplish a common goal.

Competition between organizations for scarce resources. In the past, this was usually food, while now it is usually revenue. This competition forces organizations to embrace new technologies, skills, and processes to out-compete other organizations. It also forces people within the group to cooperate more closely and enables new organizations to be founded and older organizations to fail.

People copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems. This enables innovations that work to spread into new companies, new sectors of the economy and new geographical regions. This step is critical to ensure that progress is widely shared.

Consumption of vast amounts of useful energy. Without energy, none of this can happen. Today the vast majority of that energy comes from fossil fuels.

Each of the above are explained in greater detail in the linked article.

The list above can be thought of as the most important factors in how progress works. For lack of a better term, I will borrow a term from biology and call them “behaviors.” They are tasks that humans instinctively perform. Some of them are presumably encoded in our DNA, while others are conditioned by culture.

It is important to note that these behaviors are not the ultimate causes of what gets progress started. This is a mistake that many thinkers make, and it causes their advice to be unhelpful.

The Five Keys to Progress are the ultimate causes that create the initial conditions necessary for progress. How Progress Works explains in more detail specific human behaviors that make progress work while the Five Keys to Progress are in effect.

Looking Back At Our Metrics

In my book, From Poverty to Progress, I examined two dozen metrics of progress. You can see a few examples in this Substack column on the metrics of per capita GDP, the United Nations Human Development Index, poverty rates and happiness. You can read more Evidence of Progress.

Progress on each of these metrics involves the innovation of new technologies, the mastering of new skills required to build and use those technologies and the innovation of complex and diverse social organizations designed to most effectively apply those technologies and skills to solve a problem. These solutions invariably need some sort of energy source for them to work.

To pick one example, the metrics related to health that I examined in my book (longevity, neonatal mortality, sanitation, drinking water, etc.) are driven to a large extent by technological innovations. These innovations include vaccinations, antibiotics, flush toilets, plumbing and sewage treatment systems.

Even simple medical technologies such as the medical thermometer, stethoscope, and hypodermic needles made it far easier for doctors and nurses to identify symptoms before treating diseases. More recent innovations, such as X-ray imaging, cardiac pacemakers, CT scanners, MRI scanners, prosthetics and pacemakers have made even greater contributions.

But each of these technologies requires skills. Each technology needs to be designed, produced, tested and distributed by companies that specialize in those fields. Just as importantly, doctors and nurses need to go through years of training to use them properly. Without those skills, these technologies would be no more useful than a rock lying on the ground.

In addition, social organizations had to evolve to coordinate all these skills and technologies. Corporations that manufacture medical devices had to be founded and staffed with people possessing the necessary skills. Hospitals had to be founded to coordinate all the doctors, nurses and administrators necessary to deliver diagnosis and care. Health insurance companies and government programs had to be founded to finance the payment for these services.

Those organizations in turn compete against each other for resources, usually in the form of revenue. They also compete for customers, investors and employees. Without this healthy competition, these organizations would be much less innovative. And they would not search as hard for “best practices” among their competitors.

And without vast amounts of energy, none of this would have been possible. Factories, hospitals, medical schools and other institutions require access to a stable, efficient electrical grid. The electricity in that grid is typically generated by fossil fuels, nuclear power or hydroelectric power. Fossil fuels are also necessary for the transportation of people and goods domestically and overseas.

Virtually all of these innovations started in either Northwest Europe or North America. This tiny portion of humanity has made the lion’s share of innovations in technologies, skills and social organization.

In doing so, they pioneered solutions that are useful for all of humanity. These innovations were largely made to solve local problems, but once they were made, other people could see the results, purchase or copy the technologies, learn the skills and copy the social organizations.

Just as importantly, manufacturers figured out how to drive down the manufacturing costs for products that were at first luxury items. Only the wealthiest people could afford to buy these technologies when they were in their infancy. These wealthy customers gave companies a critical early market that paid for learning the skills and processes necessary by turning these expensive prototypes into affordable necessities. Corporations drove down the price enough so that poor people and poor nations could afford many of them.

When human beings live in the proper social and natural environment, they create societies that are vast problem-solving networks. When they live outside that environment, humans are only a little more innovative than chimpanzees.

Human history has been a long, drawn-out set of trial-and-error experimentations that has resulted in some human societies becoming vast problem-solving networks. This gives other societies the opportunity to copy them, though they often choose not to do so.

In modern societies we humans live in social environments where we can innovate technologies, learn skills related to those technologies and form social organizations that best utilize those technologies and skills. And we live in social environments that enable us to copy the innovations made by others.

Are These Behaviors Unique to Today?

It is important to note that all of these behaviors have been in existence since the advent of modern humans hundreds of thousands of years ago. Humans have always invented new technologies, learned new skills, cooperated in organizations, competed as groups against other organizations, copied other humans and consumed energy. It is quite likely that our hominid ancestors also performed behaviors that strongly resembled ours.

But until the Five Keys to Progress were acquired, the amount of change caused by these behaviors was so slow that they did not deliver progress – “the sustained improvement in the material standard of living of a large group of people over a long period of time.” They delivered long, slow change, but no progress.

Before the Five Keys to Progress, human societies evolved without producing any progress for the masses. After the Five Keys to Progress came into being, human societies generated progress.

Even non-human animals can perform each of these behaviors to at least some degree. But no non-human animals perform each of these behaviors to the degree that modern humans do and with such a wide diversity of outcomes. The exception is, of course, that all animals consume energy because they must do so to survive.

Some non-human animals use tools and, presumably, those were “innovated” at some point. Beaver dams, bird nests, dolphins using sponges and chimpanzees using sticks are just a few examples. Only humans, however, have created a suite of technologies that is both vast in scope and enormous in diversity. Not surprisingly, some thinkers see this as what makes humans unique within the animal kingdom.

The same goes for skills. All non-human animals have skills (which biologists call “behaviors’). Presumably, those skills are largely encoded in their DNA, and in some species, the mother teaches additional skills. But no non-human animals have developed the enormous variety of skills that humans can perform. Juggling, ice skating, computer coding, writing books, archery, meditation, contemplating the meaning of life are just a few skills that some humans can perform. No other animal comes even close.

And the degree to which humans specialize in skills and get better at them is also unique. Some humans can juggle, but most cannot. Most people could probably learn to juggle, but they have chosen to specialize in other skills. It is not even clear that non-human animals can “choose” to specialize in a particular skill at all. Social insects specialize and many animals have gender roles, but these seem to be encoded in DNA.

All social animals cooperate in groups, but they all cooperate in groups that are virtually identical to each other. If you understand the dynamics of one pride of lions or one school of herring, you can presumably understand the dynamics of all prides of lions and all schools of herring. Non-human animals have almost no diversity in the type of groups in which they are associated.

Humans cooperate in families, bands, clans, tribes, nations, empires, corporations, labor unions, charities, schools, churches, hospitals, factories and numerous other types of organizations. Each of these organizations has different characteristics because humans voluntarily formed them to solve different problems. As far as I know, there is no analog in the animal kingdom.

In addition, a single individual human can cooperate in many different groups at the same time. I can cooperate within my family, my neighborhood, my metro, my nation, the company of my employer, my labor union, my favorite charity, and my church at different times. Modern humans naturally do this all the time without thinking much of it. This too has no known analog in the animal kingdom.

Because there are limited resources, these organizations are forced to compete against each other. The same is true of all territorial social animals. They compete ferociously to protect their territory and sometimes to expand into the territory of rival groups. Their competition is zero-sum.

Humans are also territorial and engage in violent competition. We call that competition “war.”

But humans have also created an enormous variety of organizations that solve problems for people outside the group. Those organizations compete together non-violently, often in the marketplace. This non-violent competition encourages people to innovate technologies, learn skills, cooperate more closely within those organizations and create new organizations with different characteristics.

So what do we take from all this? It is clear that these modern human behaviors that drive progress started to evolve long before even our hominid ancestors. This is an important finding because it links modern progress to biological evolution.

Humans have evolved behaviors that greatly increased both the magnitude and the diversity of non-human behaviors that have probably existed for tens of millions of years. It is only when these human behaviors are combined with The Five Keys to Progress that we see the emergence of modern progress.

So, enough about the animal world, let’s get on to the modern human behaviors that drive progress.

In the next article in this series, I will discuss Technological innovation. This includes radical innovations such as the railroad, electrical grid, computers, and the internet, as well as the ongoing incremental improvement and differentiation of thousands of other existing technologies.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Read more articles on How Progress Works:

People learning new skills to support those technologies.

Competition between organizations for scarce resources.

People copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems.

Consumption of vast amounts of useful energy.

“Under the right conditions, societies become a vast decentralized problem-solving network that generates progress.”

By right conditions, I assume you mean something beyond the 5 preconditions. Correct?

What is the role of liberal philosophical worldview (such as Locke and Smith), and the liberal institutions that emerge out of this worldview (rule of law, representative government, property rights, free markets, freedom of speech and assembly, science, etc) in creating these conditions? Is this liberal mind set necessary?