Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

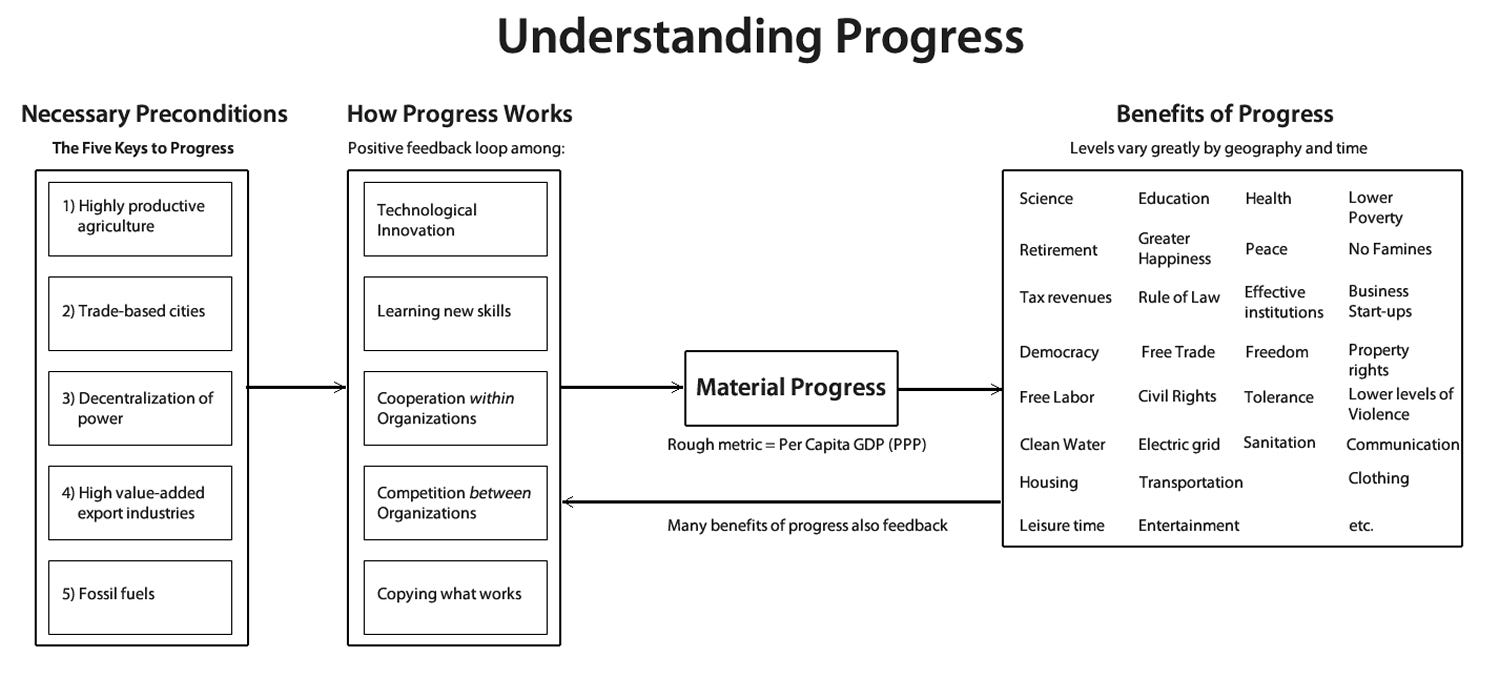

In this series of articles, I explain How Progress Works in greater detail. Once the Five Keys to Progress create the necessary pre-conditions for progress, societies become a vast decentralized problem-solving network that generates progress. So far I have discussed a few of the factors in how progress works:

Technological innovation. This includes radical innovations such as the railroad, electrical grid, computers and the internet, as well as the ongoing incremental improvement and differentiation of thousands of other existing technologies.

People learning new skills to support those technologies. Without these skills, technologies are not useful, a fact that is often forgotten.

People cooperating within organizations. Those people work together using a wide variety of skills and technologies to accomplish a common goal.

Today’s topic is the fourth factor in how progress works: Competition between organizations for scarce resources.

In the past, this was usually competition for the food surplus generated by farmers, while now it is usually competition for revenue. This competition forces organizations to embrace new technologies, skills, and processes to out-compete other organizations. It also forces people within the group to cooperate more closely and enables new organizations to be founded and older organizations to fail.

Everyone wants a cushy life without having to work too hard for it. Of course, each individual defines “too hard” in their own way. Some want to do nothing, while some voluntarily drive themselves to work 60+ hours per week. Most of us fall somewhere in between.

Just as important, organizations want a cushy existence with a steady stream of revenue regardless of results. Because all societies have finite resources, we need to ensure that those resources are used wisely.

It is critical for the success of a society that individuals and organizations are not allowed to achieve this wonderful state.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Agrarian societies created extractive institutions

To understand the importance of non-violent competition, we need to understand what came before it. A key development in Agrarian societies was the creation of extractive institutions.

While informal classes dominated Horticultural societies, elites within Agrarian societies formed impersonal institutions. Warriors were institutionalized into armies. Priests were institutionalized into churches. Royal followers were institutionalized into royal bureaucracy. Merchants were institutionalized into royal monopolies.

The goal of these institutions was to:

Extract the food surplus from farmers via taxation and land rents

Enable elites to flaunt their social status via conspicuous consumption.

Build powerful armies to defend from foreign elites and conquer additional land.

Terms of competition were tightly controlled from above

Behind every one of these goals was the threat or use of violence. These institutions were also tightly controlled by elites who had a monopoly on the tools of violence.

While today we live in a society with thousands of institutions – corporations, churches, charities, clubs, and relatively autonomous local governments – Agrarian institutions were far more limited in scope. In any one domain Agrarian elites believed that:

there must be only one institution in each domain

each of those institutions must be highly centralized

those institutions existed at the pleasure of the monarch or emperor.

Elites in Agrarian societies kept a very tight rein on the institutions that were allowed to exist. The king or monarch established royal monopolies in the political, economic, military, and religious spheres. No new institutions were allowed to exist without royal permission. Inevitably, royal bureaucrats and their followers staffed these institutions and made sure that they followed the dictates of the sovereign.

New institutions with new ideas were expressly forbidden unless the monarch could be convinced it was for his benefit. Because new institutions play a key role in innovating new technologies and skills, these royal monopolies deadened innovation.

Institutions in Agrarian societies were overwhelmingly government-sponsored monopolies whose aim was to extract wealth for the benefit of elites. Competition, diversity, and decentralization represented potential threats to the established order, so they were not allowed.

These centralized, non-competitive monopolies tended to stifle innovation. Monopolies stamp out much of the variation that makes innovation possible. Except for the areas of military and elite consumption, Agrarian societies tended to experience diminishing rates of innovation over time.

Commercial societies invented inclusive institutions

Perhaps the most important innovation of Commercial societies was inclusive institutions. Just so we are clear on definitions, I define Commercial society as a type of society that:

The majority of its food calories are purchased from the marketplace. Most people produce a good or service to earn the money to buy food produced by others. This is very different from all previous types of society where the vast majority of people produced their own food directly.

Lacks widespread use of fossil fuels, which is a defining characteristic of the Industrial societies that we live in today.

Famous examples of Commercial societies include the:

Many (most?) of the city/states of Ancient Greece

Medieval city/states of Northern Italy (Venice, Florence, Genoa, Milan, and many more)

Late Medieval city/states of Flanders (Ghent, Bruges, Ypres, and Antwerp in modern-day Belgium)

The Dutch Republic (1579-1795)

Pre-industrial England, particularly in the southeast (roughly 1500-1800)

While centralized extractive institutions dominated Agrarian societies, elected mayors and town councils ran Commercial societies. Local militia filled with free citizens defended the cities from invaders. Guilds competed with each other for economic gain and political power. Many cities had a variety of religious institutions competing with each other for worshipers.

As Commercial societies saw the benefits of having elites compete against each other non-violently based on transparent rules, this competition was institutionalized into:

Constitutions with limited government power

Individual rights, such as freedom of speech and the press

Autonomy for local and regional governments

Separation of power between executive, legislative, and judicial branches

Rule of law enforced by an independent judiciary

Deinstitutionalization of state churches and freedom of religion

Civilian control of the military

Corporations competing against each other in a market-based economy

Non-profit institutions taking the lead in health care, education, science, and social welfare

Media organizations competing against each other rather than being mouthpieces for the elite

None of these were perfect by modern standards, but they were all recognizably modern in comparison to other societies at the time. It is also important to notice that transparent non-violent competition occurred before the establishment of these institutions.

And the masses decided the winner

Whereas the elites controlled the terms of competition before the rise of Commercial societies, now increasingly the masses did. Regular people now had a reasonable range of choices and could choose the institution or group that best supported their material interests and values. The elites running and managing those institutions realized that to win one needed to produce benefits for regular people:

Even though the franchise was very restricted, political leaders had to create benefits for voters.

Merchants had to deliver high quality and/or low prices for their customers

Guilds needed to create benefits for their members

Religions had to deliver satisfying religious beliefs that appealed to their followers

Military leaders had to deliver military victory for their soldiers.

Non-profit institutions had to deliver results for their donors.

The press had to deliver relevant news to their readers

In addition, because there were multiple Commercial cities in one compact geographical area, regular people now could migrate to a city that best supported their material interests and values:

Residents could migrate to the cities that prospered

Skilled artisans could migrate to the fastest-growing industrial centers

If any one of these persons or institutions took the masses for granted, there would be another person or institution who was willing to step in to fill their place. This was far from modern democracy and markets, but it was a huge change from how Agrarian regimes worked.

It’s about the competition, not the institutions

An important point that is commonly missed is that it is not the institutions that matter, so much as the practice of transparent, non-violent competition.

The competition came first, and it evolved informally. Typically, it would be one individual who would notice the benefits. Then another would follow his example.

As the practice expanded, informal rules would emerge. Then formal institutions were created as the practice scaled up. The institutions merely ratified and formalized the competition that was already taking place in Commercial societies.

The key factor is that the terms of competition:

Enable the creation of new institutions based on new technologies, skills, and business models.

Allow existing institutions to collapse from lack of revenue due to competition from new institutions.

The “rules of the game” are known to all and outsiders can see who is playing by those rules and who is not

The rule-makers do not try to change the rules to favor certain competitors (because they will inevitably choose large existing institutions over new institutions)

The competition is non-violent.

The final factor is that the resource being competed over is scarce.

The resource is typically in the form of a food surplus (most important in the past) or money (most important today). Material reality has a way of taking care of this one, so it is rarely a problem.

Without those factors, all institutions can devolve into monopolies.

It is important to note that the same institution can exist within a system of competition or as a monopoly. And which it is will greatly affect the effectiveness of the institution in promoting progress. In addition, different arrangements of institutions can lead to the same levels of transparent non-violent competition. So while academics focus on institutions, it is the terms of competition (or lack of competition) that matter most.

Many very similar political, economic, military, and religious institutions existed in Agrarian regimes and modern authoritarian regimes, but they did so as monopolies. So it is the transparent non-violent competition between institutions that matters more than the institutions themselves.

Competition between Commercial cities and states

Just as importantly, each of the Commercial cities competed against each other. One commercial city alone is unlikely to lead to transformative progress. But a constellation of Commercial cities in the same region with defensible borders and navigable waters can lead to transformative progress.

Many different cities competing against each other ensured that their institutions could not devolve into cozy monopolies run by elites. Even if a small group of merchants or guilds could control one city, they could not control all Commercial cities. Any extractive institution within a specific city that undermined innovation would cause the city to decline and another city to rise up to take its place.

So Commercial societies competed on four different levels:

Competition between individuals within institutions based on merit.

Competition between institutions based on the output of their product

Competition between cities within the same society (for example Venice, Milan, and Genoa competing within Northern Italy)

Competition between entire Commercial societies (for example England competing against the Netherlands).

Granted, there was plenty of violent military competition between cities and societies and plenty of corruption within institutions, but the levels of non-violent competition were far higher than in any previous society. It was this Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power (the third Key to Progress) that enabled progress to get started in Commercial societies. Success was no longer about climbing up to the top of centralized royal monopolies. It was now necessary to out-innovate the competition.

Because there are limited resources, usually in the form of revenue, organizations are forced to compete against each other for survival. This competition forces each organization to adopt new technologies, hire people with skills in those technologies, and adopt new processes to most effectively coordinate these technologies and skills. In this way, organizations that compete against each other facilitate progress.

Modern Monopolies

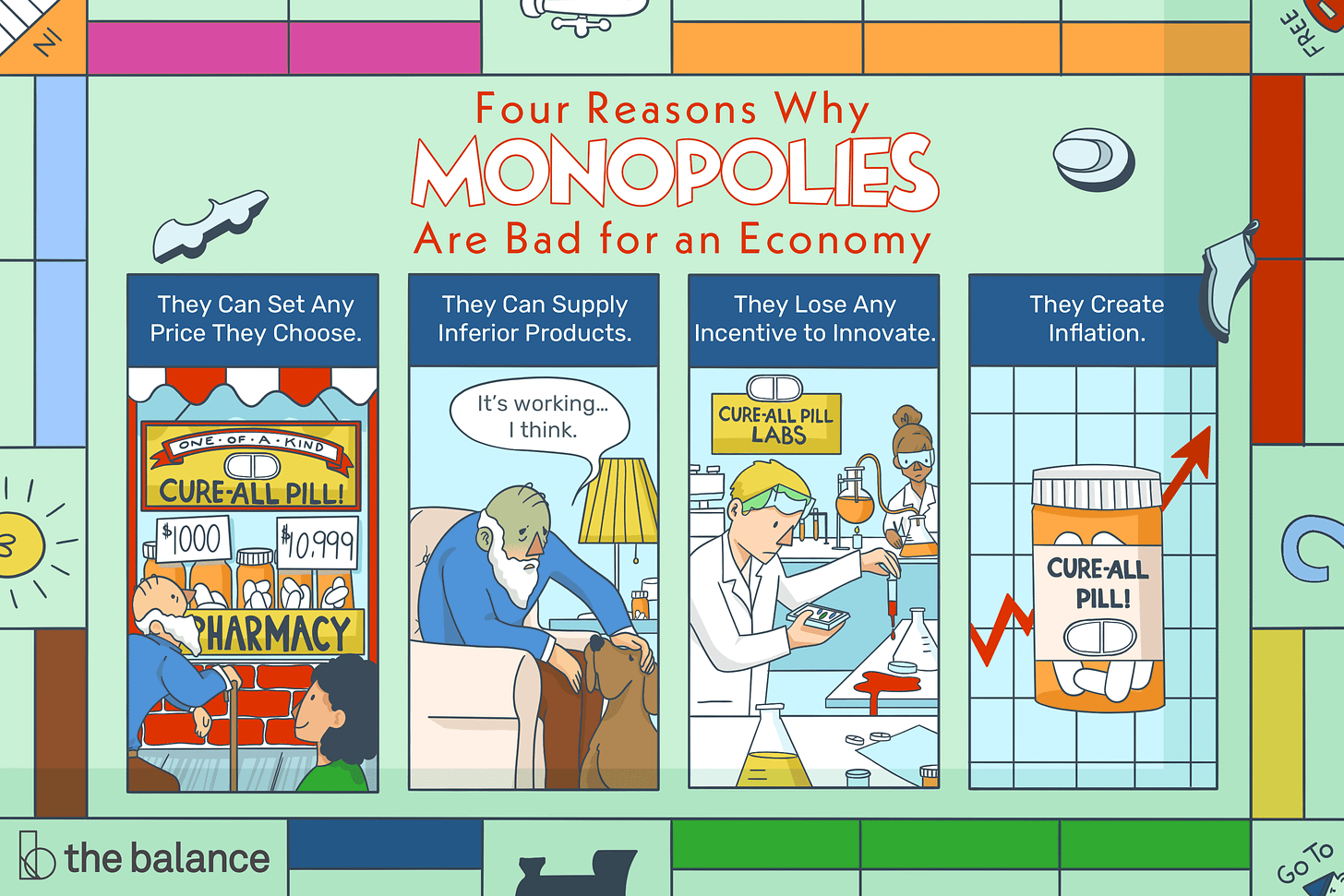

Unfortunately, the Agrarian legacy of monopolies continues to this day. Most commonly these are governments or government-sanctioned private monopolies. Because these types of organizations are insulated from competition, they have little desire to adopt new technologies, skills, or processes. This does not stop progress, but it does slow it down considerably. The higher the proportion of the total economy that is controlled by monopolies, the slower the progress.

Most organizations would prefer to be a monopoly. Being a monopoly creates a steady stream of revenue without the need for unsettling change. Monopolies create a comfortable internal environment for the members of that organization. No one has to improve or change in any way to maintain a steady flow of revenue.

The winners of a monopoly are its members, particularly those at the top who control the organization. The losers are the rest of society.

Because the benefits of being a monopoly are so great, most organizations try to become one. Businesses push governments to enact regulations, tariffs, subsidies, or loopholes to gain an advantage over their competition. Businesses often try to buy start-ups that could potentially grow into dangerous competitors. They also narrow their product line so that they can gain a significantly larger portion of a smaller market, enabling them to have more influence over prices. Businesses sometimes form cartels to fix prices.

Governments, in particular, want to preserve their monopoly. Those who work in government are naturally suspicious of private organizations that can potentially out-compete them. There has also been a long-term trend within the wealthiest nations for centralized governments to grow at the expense of local governments. While local governments are often forced to compete against each other, centralized governments can often avoid this. There has also been a long-term trend of international organizations growing at the expense of national governments.

All of the above suggests that we should be deeply suspicious of monopolies. While it is likely that some monopolies are inevitable, most are not. Limiting the number and size by promoting transparency and competition should be one of the key goals of government policy.

Of particular importance is enabling new organizations to start up and old uncompetitive organizations to fail. As long as government policies make it difficult for new organizations to be founded, it will be much easier for existing organizations to maintain their power. In addition, if government policies try to maintain existing organizations even when they are not delivering benefits to society, this will tend to stifle progress.

Cooperative Competition

As societies get more complex, they spawn a greater number of more specialized social organizations. Because even the wealthiest societies have limited resources, each of those organizations competes against each other for those resources. And societies that inhabit the same region typically competed against each other militarily for survival.

As Peter Turchin argues in his book Ultra Society (summary here), this competition between social organizations increases the level of cooperation within each of the groups. We tend to think of cooperation and competition as opposites, but the two concepts are closely related. Competition between organizations increases cooperation within organizations.

I call this phenomenon “Cooperative Competition” (Turchin and biologists use the term “Multilevel Selection”, but I think my term is easier to grasp). You can see a schematic of the phenomenon below:

Cooperative Competition is most easily seen in team sports. A team that has practiced and played together for years has a distinct advantage over another team that has never practiced together before, even if the latter is full of superior athletes. The more experienced team has worked out all the subtleties in meshing together skills and communication that enable teamwork.

It is the same for any organization.

Being involved in a continual “us vs. them” struggle also fosters a culture that tends to contain the desire of individual members to free ride on the efforts of others within the group. Humans working within groups in competition against other groups have an amazing ability to subordinate their desires in favor of the needs of the group. They do so for the very reason that the survival of the individual is intrinsically tied to the survival of the group.

Competition between social organizations also fosters innovation. To gain an advantage over their competitors, social organizations are much quicker to innovate new technologies or copy those innovated by others. Organizations are much more likely to hire skilled workers or encourage their existing workers to learn new skills. Finally, they are also more willing to change internal processes to better utilize those new technologies and skills.

The very same organizations without competition behave very differently because their survival is not at stake. Rather than investing in new technologies, skills, or processes, monopoly organizations tend to focus on creating a stable flow of resources from the outside, whether it is via higher prices, government subsidies or increased extraction.

For this reason, a society with a few dominant monopoly institutions is far less innovative than a society with many institutions that are competing non-violently against each other for survival. Monopolies stifle innovation even if they do not intend to do so. Institutions that compete non-violently against other institutions are forced to be innovative even if they would prefer to be monopolies.

Societies that allow new social organizations to be created and old social organizations to die enable innovation to take place. This innovation leads to progress. Societies that protect entrenched monopolies and interfere with the creation of new organizations that compete with those monopolies stifle innovation and undermine progress.

Prices

The mechanism that links these individual social organizations into a much larger problem-solving network is free-floating prices. Prices give incentives and they communicate information. If the price of an item or service is high enough that businesses can produce more of it while earning a profit, this communicates that the good or service is scarce. It also gives a strong incentive for an organization to deliver that good or service. If the price of an item is so low that those who produce it can barely make a profit, this discourages organizations from doing so.

A key benefit of prices and markets is that they shift the focus from solving one’s own problems to solving other people’s problems. Markets are often accused of encouraging selfish behavior, but they strongly encourage actions that benefit others.

Humans in modern societies solve their own problems, but, surprisingly, they do so by solving other people’s problems first. Prices communicate which problems other people think need to be solved. People will pay more for a good or service that solves a more serious problem, so prices encourage them to solve their own problem (putting food on the table) by helping other people solve their problems.

But Free Markets alone do not deliver progress

Of course, what I am describing is a classic free market as described by economists. But free markets, in themselves, cannot deliver progress. It is only with the Five Keys to Progress that markets can do so.

Markets existed during Hunter-Gatherer times. While they undoubtedly enabled people to trade for scarce raw materials like obsidian, there is no evidence that the result was anything resembling progress. If free markets had suddenly popped into existence in the 14th Century Incan empire, the 10th Century Carolingian empire, the 20th Century Congo, or Somalia, there would have been no progress as a result.

Prices and markets are mechanisms by which the Five Keys to Progress enable cooperation over long distances, but they cannot deliver progress alone. However, as soon as the five keys join together in one society, markets with their pricing mechanism can enable progress.

Positive Feedback Loop

We have seen how technological evolution drives the acquisition of more specialized skills, which in turn drives the evolution of more specialized and complex social organizations. So just as biological evolution tends to create a greater number of species in a complex environment, cultural evolution and progress has the same effect on human societies.

But within this process, there are feedback loops that make progress even more dynamic. Humans do not just passively learn skills related to new technologies. They also push back to make the technology easier to use.

An example from the computer industry

In my profession as a User Experience Designer in the technology field, I design the software that software developers write the code for. A key part of my job is to make complex technologies easy to use.

Early in the history of digital technology, business leaders expected users to be able to use technologies as they were provided. As long as a specific piece of technology was functional and performant, they thought the technologies would sell. As a result, early software was very difficult for novices to use.

Gradually customers and businesses pushed back on software companies and demanded that their products be made easier to use. More often, they just stopped buying the product and the software companies wondered why.

A few software companies, particularly Apple Computer, realized that software products needed to be designed for ease of use. In addition, technologies were invented to make user experience design more feasible at scale. The iPhone, Cascading Style Sheets, and the Webkit browser engine played a particularly important role.

The combination of new technologies and design skills gave birth to my profession. The result is that the software market broadened beyond experts and gradually computers became something that users wanted to use in their homes.

And it was not just individual consumers who forced the software industry to adapt. Corporate consumers of software demanded that the product mesh with their overall business processes. Corporations were willing to invest in improving the productivity of individual departments, but if the output fundamentally disrupted the productivity of a dozen other departments, the cost was too great. So, just as software companies were forced to adapt to the skills of typical users, they were also forced to adapt to the processes of social organizations.

So while technological innovation forces society to adopt new skills and social organizations, the people with those skills and the people within those social organizations also forced additional rounds of innovation. The result is a feedback loop where innovations drive more innovations.

New organizations drive competition

When new corporations are created to produce and use new technologies, those organizations put enormous pressure on existing corporations that produced or use older competing technologies. In many cases, these older companies were titans of industry that looked like they would dominate their sector for generations to come. But when a new technology evolves, seemingly dominant corporations can quickly be put out of business or at least radically diminished in their market share.

In theory, dominant corporations can simply adopt the new technology, but in practice, the skills and processes of the older technology may be so different from the skills and processes of the new technology that it is not easily done. Just like animals, big organizations built to survive in a certain environment cannot quickly adapt to major changes in that environment.

Changing the corporation so that it can produce or use new technologies may force widespread cultural changes that are strongly resisted from within. Typically, the established corporation is making enough money on the old technology that they do not even think that radical change is necessary.

The existential threat of the new technology does not become obvious until after revenues start to significantly decline. Just as older corporations need additional revenues to make the change, their revenues decline significantly. This often forces the once dominant company into a death spiral that leads to bankruptcy.

When an important new technology is innovated, it creates not just a few companies but an entire industry. In some cases, the new technology spawns dozens of new industries, each dedicated to building the components and sub-components of the new technology.

The invention of the automobile is a classic example. The automobile industry grew from a gaggle of small car companies to a vast sector of the economy with hundreds of large, medium and small companies building tires, brakes, steel, glass, along with a legion of specialized repair and parts shops.

In the next article in this series, I will explain the importance of people copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order e-books at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

You can learn more about How Progress Works with these links:

People learning new skills to support those technologies.

Competition between organizations for scarce resources.

People copying successful technologies, skills, and organizations and then modifying them to solve different problems.

Consumption of vast amounts of useful energy.

Are there any situations where competition is bad?

For instance, currently government is about 50% of GDP. This seems like an outcome of median voter theorem in universal suffrage. There is an open political competition for that 50%, but it's not a market based competition.

Would it be better if people did not compete in the government influence market for such a large pie of the economy?

And how do you bring about a political economy where less of the economy is determined by political rather then market competition?

Singapore has 10% of GDP as government with essentially one party rule. France has 58% with a multi-party democracy. Japan is often called one and a half party democracy in-between at 44%.

I'm not a fan of authoritarianism but I can't help but notice that the era of limited government and high growth took place before universal suffrage in most places.

This may be my favorite article you have written yet.

Some questions/feedback…

I agree that constructive competition (my term for what you reference here) is an essential element of effective institutions. I also agree that these institutions developed to ratify and formalize the transparent competition.

What I am not so sure about though is that these same institutions can exist in a form without competition. Free markets without open competition, entry and exit are not free markets. That would be a different institution altogether. Representative government without checks and balances and competing candidates isn’t representative government. Science without competition isn’t science. Soccer without teams competing isn’t soccer.