This article is one article in my multi-part series on American Progress:

The geography of American progress (this article)

How Progress shaped the Great Power conflicts of the 20th Century

How American farmers mechanized agriculture in the 19th Century

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

A major focus of my book series and this Substack column is the geographical foundations of modern progress. In particular, I am interested in geographical factors that enable complex societies to evolve.

By complex societies, I mean:

Agrarian societies (who acquired their food calories from plow-based agriculture)

Commercial societies (who invented progress)

Industrial societies (which most of us live in today)

Today I want to explain geographical factors that enabled modern American progress. Starting around 1870, the United States has played a critical role in sustaining global material progress. Keep in mind that I am not arguing that geography made American progress inevitable. Geography was only a necessary precondition, but not sufficient in itself. In other articles, I will write about other necessary preconditions.

America has been indispensable to world progress

First a little context. I go into more details in a previous article, but for the last 150 years the United States:

Has served as a model and protector of Liberal Democratic governance.

Has been on the leading edge of technological innovation.

Has had stronger economic growth for a very long period than almost every nation in the world.

Because of the above, the United States served as an example of a market-based economy in alternative to traditional economies and socialist economies.

This long-term economic growth enabled the United States to build a powerful military that made nations experiencing progress more powerful militarily than predatory empires.

In the 20th Century the United States was willing to use its military to protect much of the world from predatory empires in World War I, World War II, and the Cold war.

After its victories in World War II and the Cold War, the United States established a global trade system that encouraged political elites around the world to choose economic development over military conquest. Without this choice, the amazing economic growth since 1990 would not have been possible.

Since 1973 the United States has served as the single largest export market for the rest of the world.

All of the above is pretty obvious to anyone who studies modern history.

North American geography

When one focuses exclusively on modern history, however, it is easy to miss the critical role that geography played in all of this. A big part of the reason why the United States was able to acquire the Five Keys to Progress is geography.

What is now the eastern and middle two-thirds of the United States was blessed with geography that made progress possible. In particular, its geography had most of the characteristics necessary to support plow-based agriculture and trade-based cities (the first two keys to progress).

In my book, From Poverty to Progress, I identified several key geographical factors that determine whether societies that live within a certain region can experience progress. Here I will briefly sketch out the geographical advantages and disadvantages of the United States. As we will see, the geographical advantages far outweigh the disadvantages.

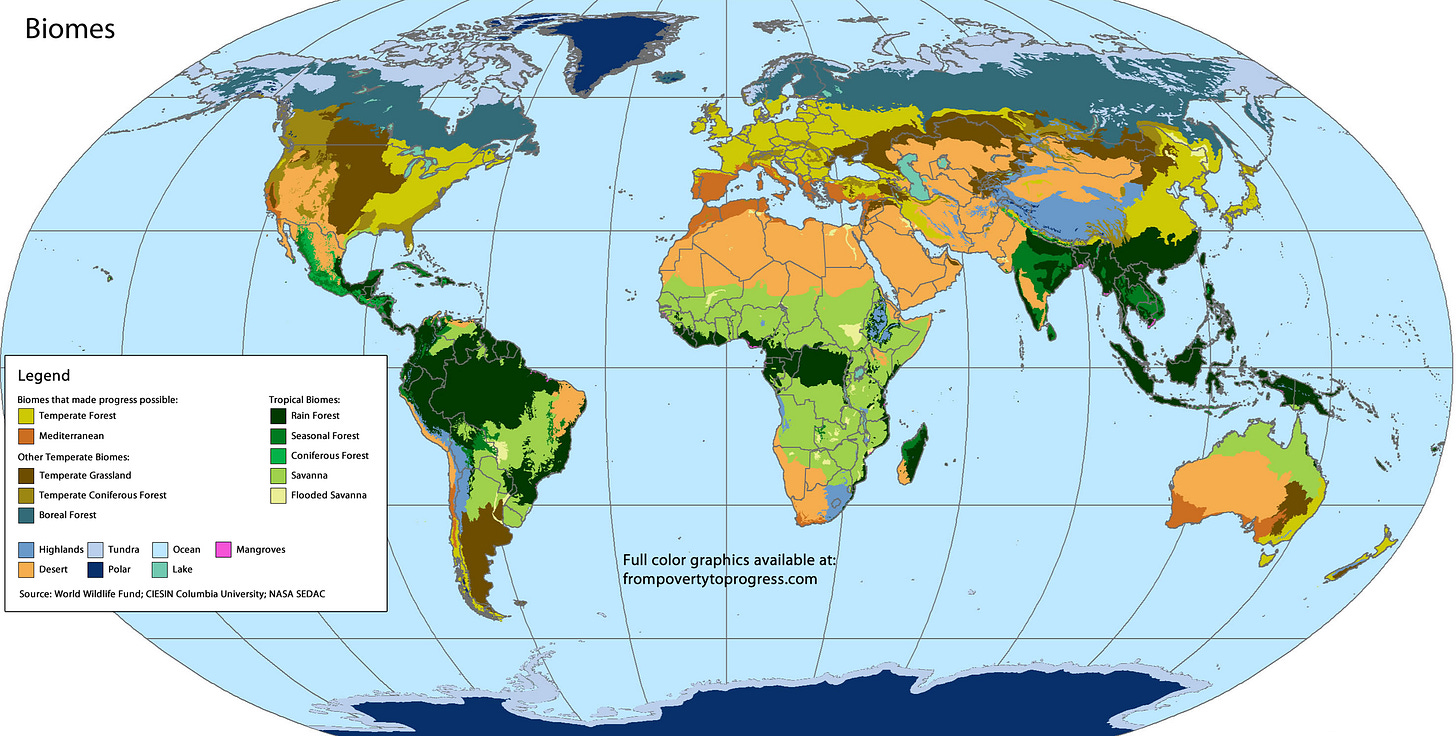

Biomes

A biome is a category for a geographical area based upon its dominant vegetation. The dominant vegetation in any area sets very broad constraints on what type of plants and animals can evolve there. The dominant vegetation sustains the local herbivores, which then sustain the local carnivores. Since humans use a portion of these plants and animals as base materials for food production, biomes also play a critical role in constraining the types of human societies that can develop within them.

Plow-based agriculture, a necessary transition step to modern progress, is only possible in a few biomes:

Temperate Forest biomes

Mediterranean biomes

(after the invention of the steel plow in 1830s) Temperate Grassland biomes

Right off the bat, most regions in the world have none of the above. Not so for North America.

The eastern third of the present-day United States is covered by a vast Temperate Forest biome. It is not a coincidence that every one of the regions with large Temperate Forests – Europe, East Asia, and the eastern United States - developed into wealthy and influential civilizations.

Temperate Forests have trees with leaves that fall off in the autumn, delivering huge amounts of nutrients into the soil. This creates very productive soil, a key ingredient in agriculture. In addition, the trees themselves give humans one of the most useful materials in the world: wood. Wood can be used for heating homes, as material for the construction of tools, dwellings, and transportation devices, and charcoal, a key first step in metalworking technology.

The middle third of the present-day United States (what we now call the Midwest). contains vast stretches of Temperate Grasslands. While Temperate Grasslands tend to have productive soil, it is covered by a dense map of grass roots. These roots are so dense, that traditional plowing cannot penetrate them. This explains why farmers considered the Great Plains into a virtual desert in early American history.

Once the steel plow was invented in the 1830s, however, the Temperate Grasslands of the Great Plains became the largest and most productive agricultural region in the world.

Soil

Even with the proper biomes, a region needs fertile soil for agriculture. Because agriculture is key to feeding dense human populations, the type of soil in a region is critical to its ability to support complex societies. Soil is the combination of:

weathered rock,

air,

water, and

organic matter from decomposing plants and animals.

North America, unlike most continents, has many regions with soil that is suitable for agriculture. Mollisol soil (dark green on the map below), the most productive soil in the world, dominates the Great Plains. Only the Asian steppe rivals it in size. Productive Alfisol soil (lighter green) is common in Upper Mississippi, Ohio, and Sacramento river basins. The northeastern United States has large areas of productive Inceptisol soil (orange).

Though not as productive as the other soils mentioned above, Ultisols (in yellow) make the southeastern United States somewhat productive. All together, virtually all of the eastern two-thirds of the United States is covered by soil that is productive for agriculture.

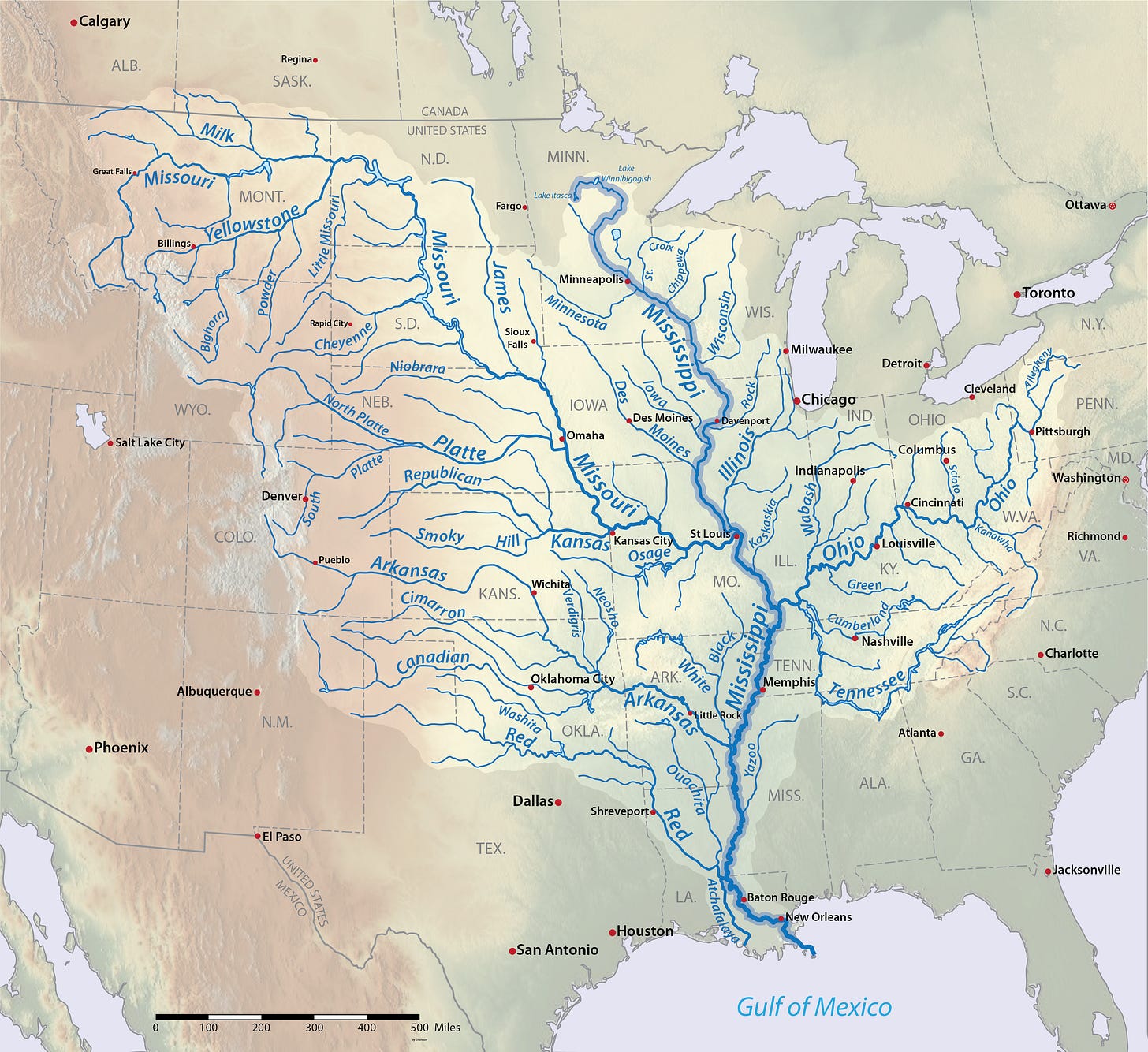

Rivers

Most large and prosperous cities are located on rivers or natural ocean ports. Rivers offer crucial advantages to human development. Rivers:

Offer sources of (hopefully) clean drinking water.

Make it easier to remove human waste.

Offer sources of irrigation for crops.

Deposit additional nutrients in the soil for growing crops.

Enable cost-effective transportation of people and freight.

Offer defensible lines to block the approach of enemy armies.

North America is blessed with a massive system of natural inland waterways:

the Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio river basin

the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes waterway.

These two enormous bodies of water form liquid superhighways for societies with advanced boating technologies. The only portion of the eastern United States that does not have large navigable rivers is the Atlantic seaboard with its many natural ocean harbors, such as Boston, New York City, Baltimore, and Charleston.

Notice also that these liquid superhighways run through relatively flat Temperate Forest and Temperate Grassland biomes. This makes it relatively easy to link highly productive agricultural regions into locations that are ideal for city formation (such as ocean ports or river junctions) long before the Industrial Revolution.

Also beneficial are the Intracoastal waterways that stretch almost unbroken between modern-day Texas on the Gulf of Mexico and Maryland on the Chesapeake bay. Except for the Appalachians, virtually every square mile of land in the eastern half of the United States is easily accessible via navigable water.

And this map shows just how massive the Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio river system is. As far as I know, this is by far the biggest river system flowing within biomes that can support productive plow-based agriculture.

Here is a really good video on the tremendous advantages that these river systems give to American industry and agriculture:

Altitude

Except for Highlands in Tropical latitudes, complex societies are concentrated on the plains at altitudes of 500 meters or lower. While landmass on Earth varies in altitude from just below sea level to 10,000 meters above, about 73.7 percent of humanity inhabits altitudes of less than 500 meters above sea level.

The bulk of eastern North America is below 500 meters in altitude. Typically, areas over 500 meters in altitude in Temperate regions are sparsely populated due to a lack of good soil and navigable rivers. The western third of the present-day United States and the Appalachian mountain chain are the only large regions where altitude is a major constraint to the evolution of complex societies. Not surprisingly, those regions are lightly populated to this day.

It is important to understand how rare this combination of geographical factors listed above was on planet Earth. East Asia and Northern Europe are the only two regions on the entire planet that have similar geographies. Not surprisingly, East Asia, Europe, and the United States have dominated the history of innovation and progress.

So why was progress delayed?

If the geography of the eastern two-thirds of North America was so conducive to complex societies, why didn’t Native Americans build prosperous societies before the arrival of European settlers? While this region had almost all of the geographical factors necessary to support such societies, they were missing one key ingredient:

a lack of native wild ancestors of domesticatable plants and, particularly, animals.

North America did have some domesticatable native plant species, such as sunflower, squash, sump weed, maygrass, goosefoot, and little barley, but staple crops capable of supporting large populations were missing. It was not until maize (also known as corn) diffused north from modern-day Mexico into the present-day eastern United States that the region could potentially support large populations.

An even bigger barrier for North America was the lack of wild ancestors of domesticated animals, except for the turkey (plus the llama and guinea pig in South America). Domesticated animals are critical to the evolution of Agrarian societies similar to Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. Without powerful animals to pull plows, agriculture had to be powered by human muscles.

Have you ever tried to convince a turkey to pull a plow?

Meanwhile, Eurasia had a long list of wild ancestors of domesticated animals, including many that could pull plows: horse, cow, water buffalo, pig, goat, sheep, chicken, dog, and cat.

Without domesticatable animals, the indigenous people of North America could not create highly productive agricultural systems based on plows. This then made it very unlikely that large trade-based cities could evolve. This made the first two keys to progress (productive food systems and trade-based cities) impossible to achieve before 1500. These geographical constraints seriously limited how far their societies could develop before the arrival of Europeans.

Ironically, horses likely evolved in North America before they migrated to Central Asia, but all prehistoric horse species died off long before agriculture evolved. Whoever (or whatever) killed the last wild horse in North America dealt a death blow to the possibilities of developing progress in that region before the arrival of the Europeans.

North American geography could support Hunter Gatherer, Fishing, and Horticultural societies (primarily growing maize using hand tools), but nothing more complex could evolve. Despite having many geographical factors that were conducive to the evolution of complex societies, the lack of domesticatable animals capable of pulling plows placed a hard ceiling on their level of development. While the Eastern and Southwestern United States developed several simple Horticultural societies, most indigenous people lived in either Hunter Gatherer or Fishing societies.

So how did this all change?

I will write many articles on this, but essentially:

Geographical preconditions + Immigrants from Commercial societies = Explosive Economic and Demographic Growth!

This article is one article in my multi-part series on American Progress:

The geography of American progress (this article)

How Progress shaped the Great Power conflicts of the 20th Century

How American farmers mechanized agriculture in the 19th Century

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Good to revisit this after a year plus. Multiple exposures are part of "fixing" info in our brains.

In reviewing your topo map, I realized why it seemed that on my recent flight from Orlando to LA that once we passed Dallas we were over desert almost the rest of the way. Sort of because we were!!

You have accumulated a great set of reference materials/ data should we need to go back and double check any sub-features.

yes, great set of charts/ graphics.

I did not realize the limitations on indigenous Western hemisphere populations was due to lack of domesticated plants and animals. But to check, lamas were native, right? Just perhaps not suitable as plow animals? Plus mountainous region not good for plowing/good soil either?

Is it also fair to say that the work effort for maize/corn was higher than wheat or other grasses for a given net nutritional value output?