In my book series and this Substack column, I have argued that for most of human history, humans have lived in a perpetual state of poverty. Humans were trapped in poverty by geographical constraints that limited food production.

Fortunately, a few societies in the Northwest were located in unique geographic and political environments. Sometime after the year 1200, a few Commercial Societies in that region acquired four of the Five Keys to Progress. This enabled those societies to experience material progress for the masses. Six historical breakthroughs enabled that progress to spread throughout much of the globe.

This article explains how Colonial North America and the United States copied the Five Keys to Progress. This process enabled the material progress that has existed for roughly 400 years.

Read more of my articles on American Progress and Upward Mobility:

How the USA copied the Five Keys To Progress (this article)

Upward Mobility in the USA until 1930 (coming soon)

Upward Mobility in the USA 1947-1965 (coming soon)

Why did the American South develop so differently? (coming soon)

Traditional Pathway to Success (coming soon)

Note: I also have a large number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. These excerpts are only available to paid subscribers.

Copying the Five Keys to Progress

In From Poverty to Progress, I argued that copying successful innovations made by others is the fastest way to move ahead. In theory, this should be easy. Each person should look around at all the technologies, skills, and organizations of the most successful people and then copy as much as possible. In practice, it rarely works that way.

One of the key barriers to copying successful innovations is cultural differences. People tend to view their own culture as superior to others, or, at the very least they are simply more comfortable with their own culture. This makes copying people from the same culture far easier than copying people from different cultures. The greater the perceived difference between cultures, the less likely a person is to copy innovations made in that culture.

Because the Five Keys to Progress were invented by Northwest Europeans and British North America was largely settled by those same people, the cultural differences between the United States and Northwest Europe were relatively limited. This in combination with nautical transportation and communication technologies made it relatively easy for Americans to copy the Five Keys to Progress from Northwest Europe.

One individual copies

All it took was for one ambitious entrepreneur, engineer, or skilled American worker to copy a successful technologies, skills, and social organizations. Because doing so would put them at a competitive advantage over all others, one individual could rapidly establish and scale up a business.

With low trade barriers, vast river and inland sea transportation pathways, communication technologies, and a common culture, these original “innovations” rapidly diffused throughout the region. This sometimes occurred by the original company growing national in scale, but more often it happened because other organizations copied the copiers.

Once the United States copied the Five Keys to Progress from Northwest Europe, they set off a chain of events that led to enormous progress and upward mobility. With productive agriculture, growing trade-based cities, a decentralized political, economic and religious system, and export industries, a large portion of society could focus on solving problems by innovating new technologies, skills, and social organizations.

Just as important with a common English language and Christian religion, there were no fundamental cultural barriers that stopped sub-groups from copying innovations in other regions. A vast, efficient transportation system based upon rivers, oceans, roads, and later rails made it easy for innovations in one city to rapidly spread throughout the nation.

An equally efficient communication system based upon the telegraph, newspapers, books, and later radio and television made it easy for citizens in one region to be aware of innovations made in other regions. Never before had such a vast geographical area experienced so much progress and upward mobility for such a long period.

Key #1: Agriculture

The first key to progress is to evolve a highly efficient food production and distribution system. This enables large numbers of people to overcome geographical constraints, so they can focus on solving problems other than producing enough food to survive.

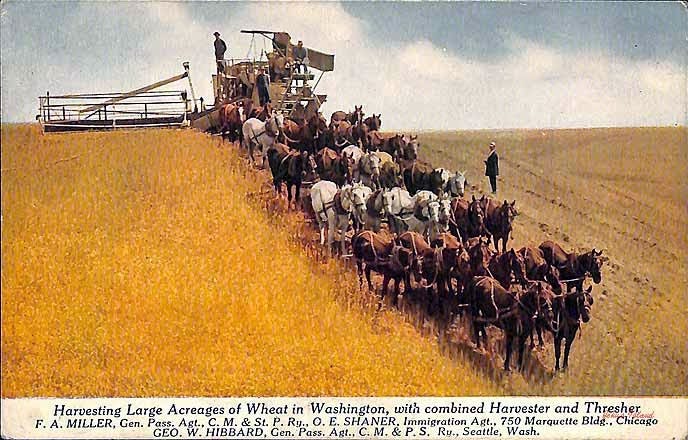

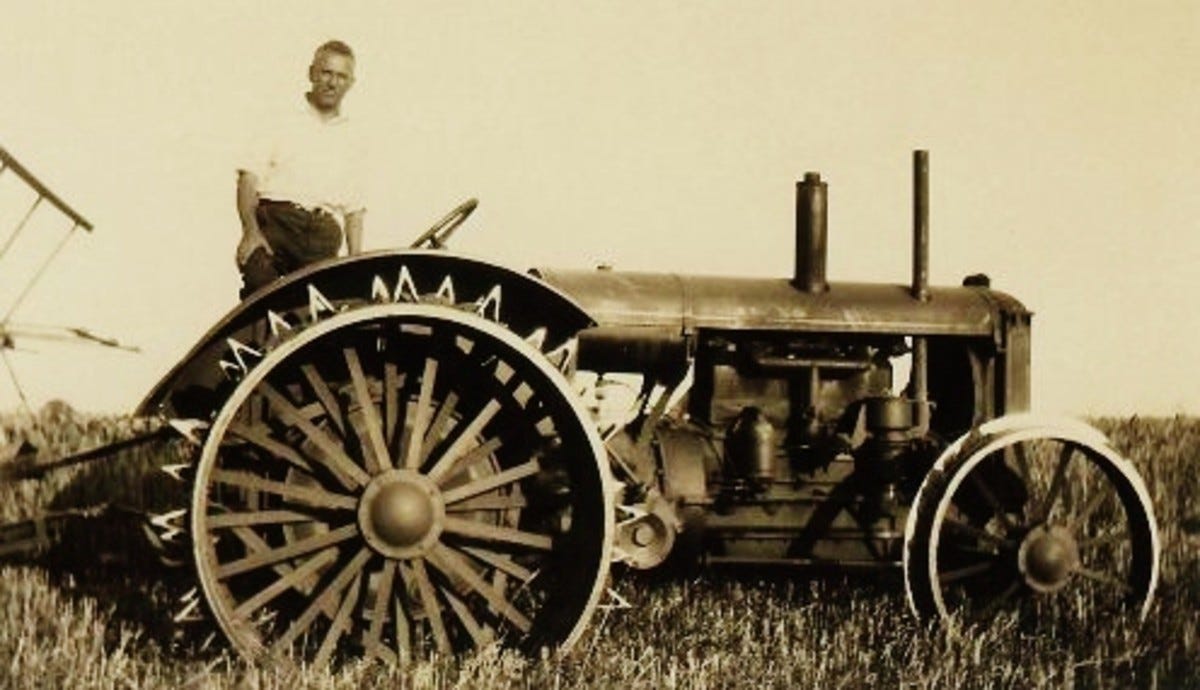

European settlers brought new crops and domesticated animals with them. They produced plows and other farming technologies that copied those they remember using in the Old Country. They then modified those technologies so that they suited the unique North American environment. They also copied and modified the skills and processes necessary to run a productive farm.

European settlers also brought with them triple-masted ships and the knowledge of how to construct horse-drawn wagons. This made it much easier to distribute the farm surplus to neighboring towns and cities. At a later date, Americans copied steamboats and railroads invented in Britain that revolutionized the transportation system.

Within a few generations, the people of British North America and the United States built the most productive food and distribution system that the world had ever known. More importantly, that system continued to keep on improving up to the present day.

Key #2: Trade-based Cities

The second key to progress is to evolve a network of trade-based cities full of free people with a wide variety of skills. These people innovate new technologies, skills, and social organizations and copy the innovations made by others.

With the highly productive food production and distribution system and no extractive elites, it became relatively easy to establish trade-based cities. These cities were modeled on the trade-based cities of England and the Netherlands.

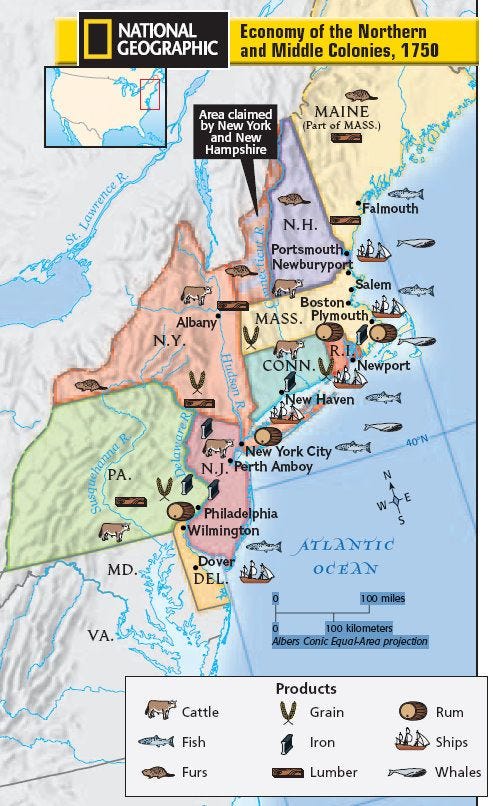

Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore grew into thriving trade-based cities. Smaller cities such as Salem, Newport, Providence, Marblehead, and Portsmouth did the same. It is not a coincidence that these cities were established by settlers from the most commercialized cities in Europe. All of these cities were deliberate copies of the extraordinarily innovative trade centers of Northwest Europe.

While Europe and Asia were dominated by huge capital cities that thrived by expropriating the food surplus from the peasantry, the United States evolved a constellation of prosperous trade-based cities competing against each other peacefully. The result was four centuries of economic growth.

Key #3: Decentralization of Power

The third key to progress is to decentralize political, economic, religious, and ideological power. Of particular importance are elites being forced to compete against each other non-violently. This ensures that the benefits of innovation go to the masses rather than to the elites.

Even in comparison with the most advanced Commercial Societies of Northwest Europe, the United States was devoid of centralized power. Aristocrats, gentry, clerics, and military officers were almost completely absent from the original settlers, and what little influence they had faded quickly.

The powerful centralized institutions in Europe and Asia that extracted wealth from the peasantry via land rent and taxes were almost completely absent from North America. Political power was largely on the local level and state level. Economic organizations were at best medium-sized and local (at least until the late 19th Century).

While many of the British colonies had established religions (i.e. only one religion was allowed), this practice was abolished by the First Amendment when the United States was formed. Freedom of religion was embedded in the Constitution and established churches were illegal. Ideology, as we currently know it, was almost completely absent.

All of this meant that there were few checks on the innovative power of the emerging Commercial cities. Farmers willingly exported their food surplus in exchange for money. Urbanites consumed that food and used it to power the innovation of technologies, skills, and social organizations. Just as importantly, they copied the innovations that worked best and then modified them for new purposes.

Key #4: Export Industries

The fourth key to progress is having at least one high-value-added industry that exports to the rest of the world. This injects wealth into the city or region, accelerates economic growth, and creates markets for smaller local industries and services.

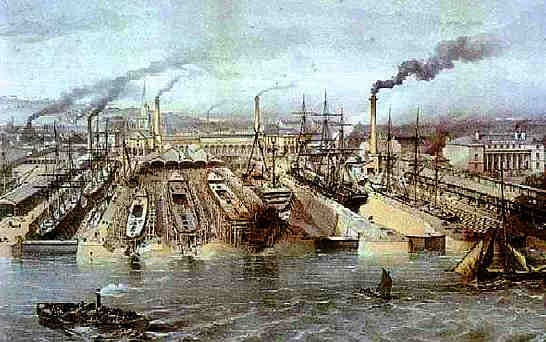

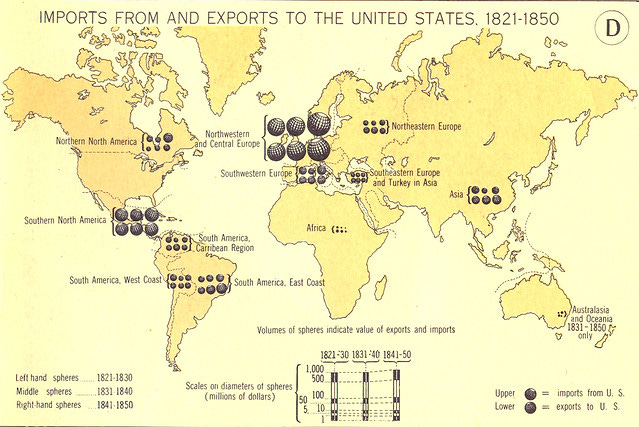

Early settlers of British North America established export industries including grain, lumber, fishing, whaling, shipbuilding, ship outfitting, iron, and furs. As the American settlers migrated west, they established even more trade-based cities: Cincinnati, St. Louis, Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Denver, Kansas City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Each evolved from empty land to thriving cities, often in only one generation. Each of these cities specialized in specific industries and trade that were appropriate for their geography.

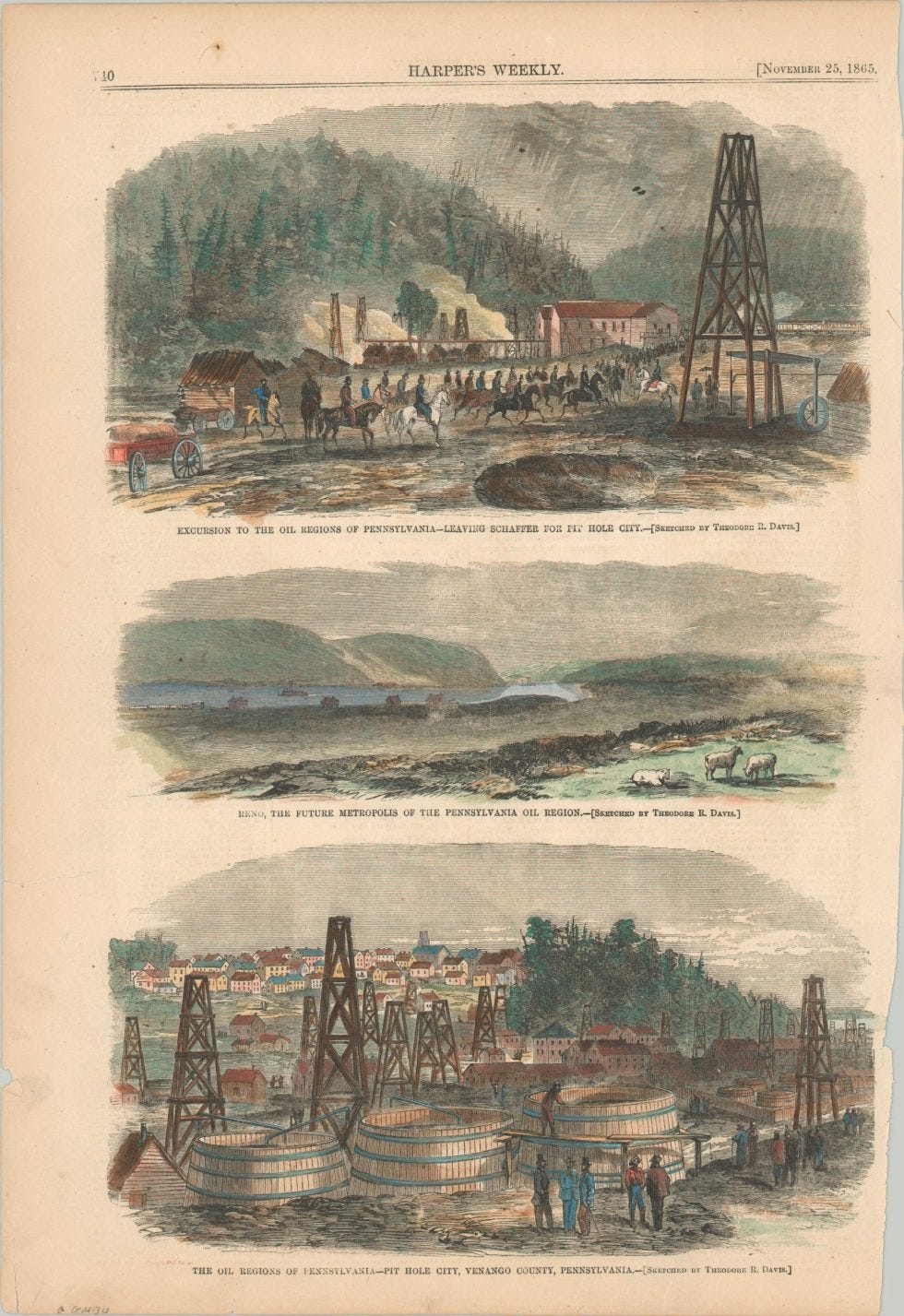

In many cases, these industries were founded by a single individual who copied British technology. Or from the British perspective, those individuals stole British technology. By copying what worked in Britain, the locals were able to grow thriving industries. Each became a center of innovation that became a target for copying/stealing by other American cities.

Each city focused on a handful of export industries with the overall national division of labor. New York City specialized in finance, Chicago specialized in commodities, Detroit specialized in automobiles, Pittsburgh specialized in steel, Los Angeles specialized in aerospace, and Houston and Dallas specialized in energy. A gaggle of smaller cities specialized in smaller industries.

Each of these trade-based cities served as a market for agricultural goods, further accelerating the growth of agricultural productivity. Each city was integrated into a sophisticated transportation network that enabled them to export to the rest of the United States and the world. The United States became the single largest economic market in the world.

Key #5: Widespread Use of Fossil Fuels

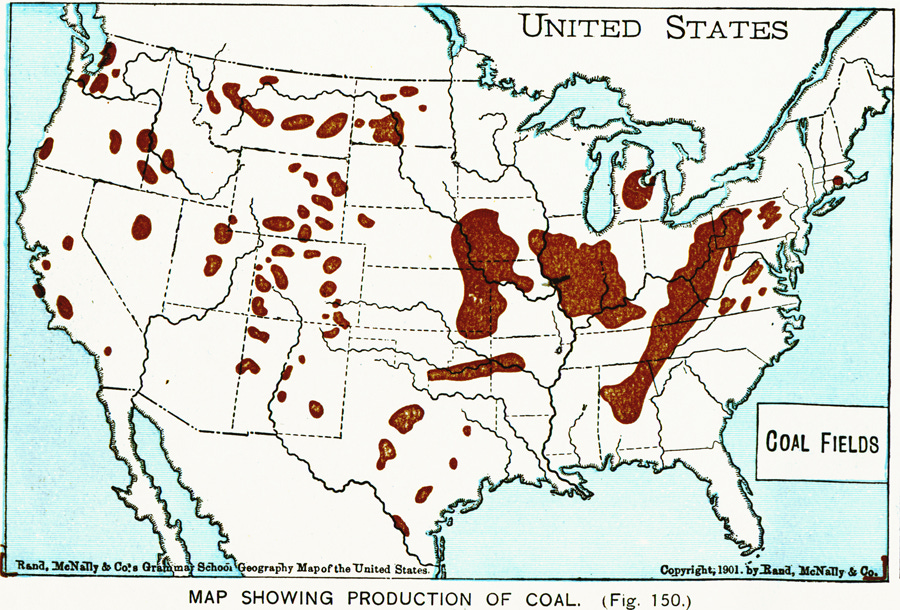

The fifth and final key to progress – widespread use of fossil fuels – also came from copying Industrial Britain. Britain was the first society to use vast amounts of coal. They first used coals for heating homes in London, but they gradually learned to apply the energy source to manufacturing, transportation, communication, and materials. The British invention of the steam-powered locomotive was one of the greatest innovations in world history.

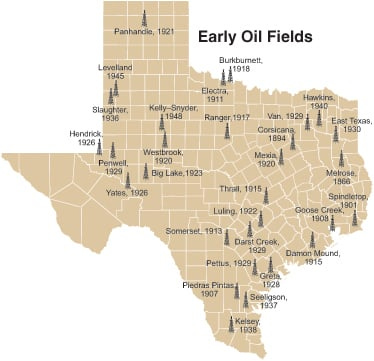

Because so many early immigrants to America came from England and Scotland, it was relatively easy for a few of them to bring industrial technologies that were created in the Mother Country. With vast supplies of coal from Virginia, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, and West Virginia, this energy source powered much of American industry in the 19th Century. Towards the end of the 19th and later in the 20th Century, the United States added vast amounts of petroleum and natural gas. Later the nation supplemented nuclear and hydroelectric power to the national energy portfolio.

Americans also used industrial technologies to make more effective use of pre-industrial energy technologies. Contrary to what one might think, the use of horses, wagons, wood, and sailing ships increased during the 19th Century. It was only with the widespread use of automobiles, steamships, concrete, steel, and glass that the older technologies declined in use.

Once Americans assembled all Five Keys to Progress in a geography conducive to their widespread use, American societies became a vast decentralized problem-solving network. This inevitably generated progress as well as upward mobility for the people.

Once the United States found out how to copy the innovations of European Commercial societies and scale them up to a virtual continent, progress accelerated radically in scope. Progress was no longer confined to a few thousand people concentrated in cities in Northwest Europe. Now tens of millions of people experienced progress.

Read more of my articles on American Progress and Upward Mobility:

How the USA copied the Five Keys To Progress (this article)

Upward Mobility in the USA until 1930 (coming soon)

Upward Mobility in the USA 1947-1965 (coming soon)

Why did the American South develop so differently? (coming soon)

Traditional Pathway to Success (coming soon)

Hi Michael. Not yet ready to give you an overall reaction to your ordering of the factors of progress, but a small historical quibble. The Bill of Rights requires prohibits only the federal government from establishing a religion. Most states abolished their established churches around the time of the Revolution. However, Massachusetts continued to require each of its towns to establish a parish/town church until 1824. See

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Separation_of_church_and_state_in_the_United_States#endnote_MA

^Note C: From 1780 to 1824, Massachusetts required every resident to belong to and attend a parish church, and permitted each church to tax its members, but forbade any law requiring that it be of any particular denomination. But in practice, the denomination of the local church was chosen by majority vote of town residents, which de facto established Congregationalism as the state religion. This was objected to, and was abolished in 1833. For details see Constitution of Massachusetts.[citation needed]

The early United States, in some sense, was a blank slate. Lacking an aristocracy or the extractive institutions of an agrarian regime, the US was able to prosper and thrive more easily by readily absorbing and combining the best ideas imported from abroad.

In some sense, the US still does.