Evidence for progress: Per capita GDP

While many people today are skeptical of progress, the evidence is overwhelming. Let's start by looking at the transformation of per capita GDP across the globe.

Measuring Progress

In this article, I will provide evidence that we live in an era of great progress, and that progress benefits the vast majority of mankind. To prove that progress is taking and has taken place, we need objective means by which to measure it. Just pointing to a few examples where progress takes place is no more definitive than pointing to a few examples where progress does not take place. We must look for overall trends.

Unfortunately, there is no one metric that accounts for all dimensions of progress. So instead, I will take a broad approach by using many different development metrics. These metrics include measures of economic growth, poverty, agricultural production, diet, sanitation, drinking water, life expectancy, neonatal mortality, education, housing, happiness and more. I deliberately cast a broad net in order to capture as many dimensions of material well-being as possible.

One of the key problems with documenting progress is finding good metrics that both go far enough back in time and that cover the entire world. Not surprisingly, there is far more data related to recently industrialized nations than those same societies in, say, 1500. Nor is it surprising that data is far easier to acquire for wealthy nations than poor nations. In many cases, I need to use different methods for different time periods and different nations. While not exactly comparing apples to oranges, it is a bit like comparing Gala and Red Delicious apples to Fuji apples. This is less than ideal, but it is hard to do otherwise.

The metrics that I use come from a wide range of official government and NGO sources. I present the metrics in a series of graphs. Unfortunately, the scope of the data is not easily digestible in static graphs. If you would like to inspect the data in more detail, I encourage you to explore a website that has spent a great deal of time gathering important metrics: Our World in Data.

Since there are over 200 nations today, it is not realistic to examine development metrics for every one of them in this book. And averages can cover up variations between rich and poor nations. We need a way to narrow the sample to a manageable number, but not in a way that creates a distorted impression of overall trends. In order to ensure that the data covers a very broad segment of the world’s population, I decided to focus on four distinct categories of nations.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See more articles on Evidence for Progress:

Book review: "Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know" by Bailey & Tupy

Long-term trends in per capita GDP (article; podcast; video)

Growth in per capita GDP (2012-2022) (article; podcast; video)

United Nations Human Development Index (article; podcast; video)

Does material progress lead to happiness? (article; podcast; video)

more.

National categories

The first group, which I will call the “Wealthy 12”, consists of 12 Western nations that industrialized early and currently have very high standards of living. Those nations are the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. The Wealthy 12 gives us a good overview of the trends within the wealthiest nations.

The second group that I will show data for is what I call the “Populous 12”. This group consists of 12 of the most populous nations that did not have high per capita GDP in 2020. This group consists of China, India, Brazil, Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Turkey. Together these nations make up 58% of the world’s population and cover every continent except Australia and Antarctica. The Populous 12 gives us a broad overview of trends for people who live outside the wealthiest nations.

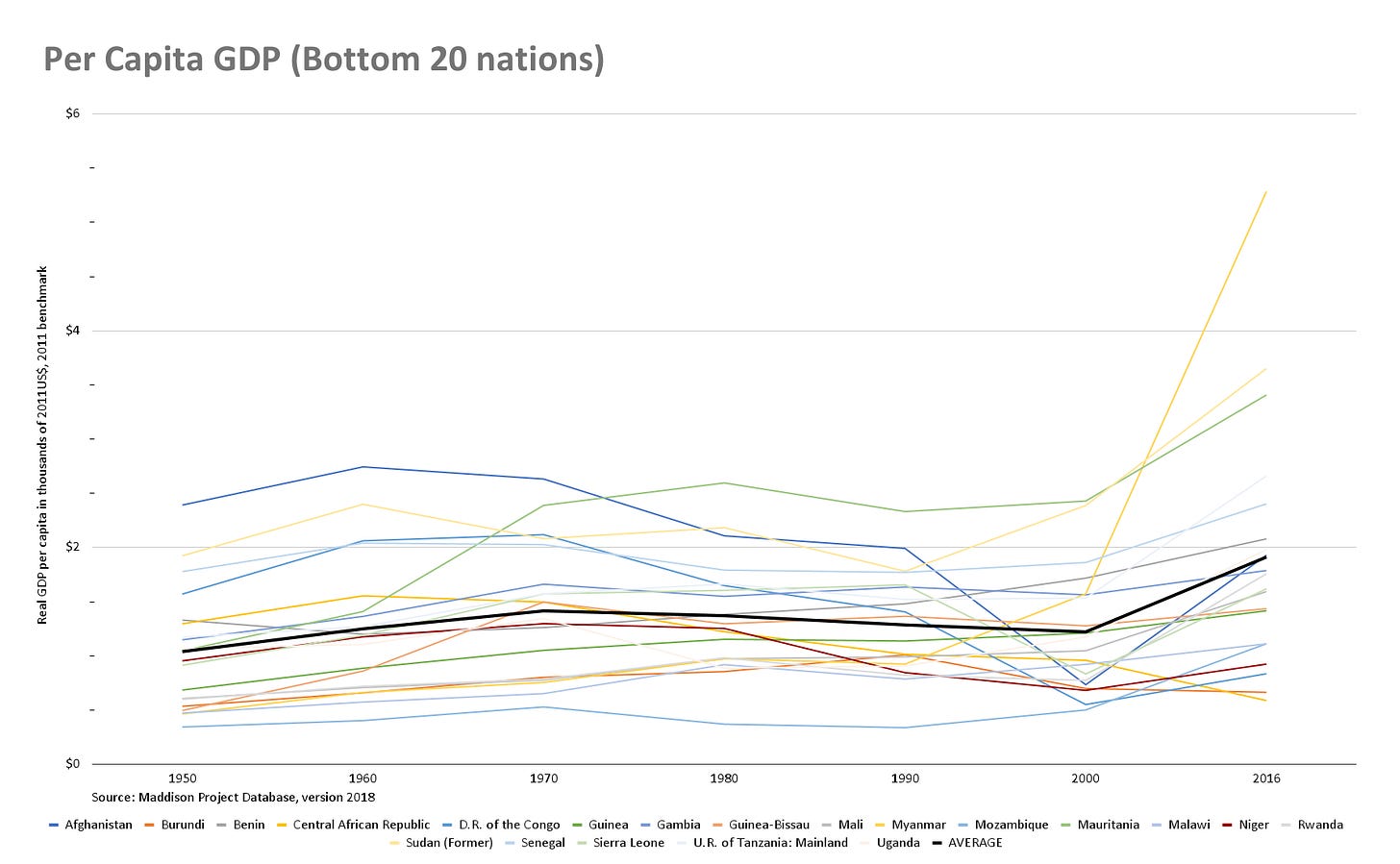

The third group is what I call the “Bottom 20”. This group consists of the 20 nations with the lowest scores on the United Nations Human Development Index in 1990 (the earliest year available). The nations in this group consist of Afghanistan, Benin, Burma, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Gambia, Guinea, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda. The Bottom 20 gives us a good overview in trends of the most desperately poor nations in the world. If there is any group of nations that should lack evidence of progress, it is these 20 nations.

The last group of nations is what I call the “Transformative 16”. This group consists of nations that experienced at least one generation of very strong economic growth after 1950 (or 20+ years of per capita GDP growth of over 3 percent). This level of economic growth would lead to a doubling of the standard of living of their people within one generation.

The Transformative 16 includes representatives from many different regions and cultures: Spain, Ireland, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, South Korea, Indonesia, China, India, Israel, Botswana, Trinidad, Puerto Rico and Chile. The Transformative 16 gives us a good overview of the nations that experienced the fastest economic growth. It tests whether very rapid economic growth translates into positive changes throughout society.

Together, the Wealthy 12, the Populous 12, the Bottom 20 and the Transformative 16 are a solid set of groups with which to test whether the world has experienced widespread progress over the last few decades. Given the breadth and diversity of the four groups it seems unlikely that any broad trends will be missed by narrowing the sample down from all nations in the world. In some cases, I will supplement these four groups with other data that seems relevant.

WARNING: Proving that progress exists requires lots of data in graphs. Some people love to dig into data, while others hate it. If you love data, this chapter is for you. If you hate it, you can skim over a few of the sections to understand the main points and then read the conclusion at the end of this chapter.

A few book-keeping notes:

Each metric varies greatly in the number of nations and years due to the availability of data. I have done my best to be as comprehensive as possible given data that is accessible on the internet. In order to facilitate visual inspection, I have added an “Average” displayed in a thick black line wherever there are more than four nations with data. This average is sometimes jagged when individual data points are missing.

Wherever data permits, I will focus on women rather than the total population to show that progress has not excluded them. Note also that the use of these categories leads to some double counting. China, India, and Indonesia are in both the Populous 12 and the Transformative 16. Congo is in both the Populous 12 and the Bottom 20.

Per Capita GDP

Economic growth is central to progress. With economic growth, it is possible to pay for education, health care, transportation, housing, and other factors that promote an increased standard of living. Without economic growth, progress becomes far more difficult because there are simply not enough resources.

Change in per capita GDP roughly measures progress. Also very important to notice is that all the other metrics that I use in this column and my book series are closely related to per capita GDP. See the bottom of this post for a partial list.

Per capita GDP loosely measures the standard of living, while change in per capita GDP loosely measures progress. This strongly suggests that economic performance is closely linked to progress.

By creating wealth, societies can purchase the technologies, learn the skills, and establish the social organizations that lead to improvements in all of these metrics. The close correlation between all these metrics of progress to per capita GDP also makes it much easier to chart progress across the globe over the last 1,000 years when we do not have data on specific metrics.

In this study, I will measure economic growth using per capita GDP in real 2011 dollars because this takes into account population and inflation. Data on per capita GDP since 1950 are widely available.

In addition, Angus Maddison has created a publicly accessible database of estimates of per capita GDP across the world going back to 1 AD. Maddison started with the current per capita GDP, and assigned a figure of $450 income per year to the poorest of societies in history. This is roughly the level of economic activity needed to support basic human survival and reproduction. He then worked backward by using available economic data to make estimates for every society in the world going back to 1 AD. These are, of course, estimates, but they do give us a rough order-of-magnitude level of the standard of living of people throughout the last 2,000 years.

For the Wealthy 12 nations, one can see the power of exponential growth of per capita GDP. From year 1 to the year 1000, the “curve” is a virtual flat line. If we had data from before year 1, we would see that this flat line had existed for millennia.

But within that apparent stagnation was very gradual innovation feeding upon itself. Somewhere around the year 1500, the rate of innovation had accelerated enough to produce an improvement in people’s lives. Since 1820, the curve has continually become steeper making the exponential nature of growth obvious.

The curve gets particularly steep after 1950 (when the data is no longer based upon estimates). With the exception of Switzerland, all nations in the Wealthy 12 had a per capita GDP of $16,000 or less (in current values) in 1950. This level of income is less than the current level for Mexico. By 2017, every nation in the Wealthy 12 had a per capita GDP of $37,000 or more, more than double the previous levels. On average, these nations quadrupled their per capita income between 1950 and 2016.

For the Populous 12, we can see a similar exponential curve, but the levels of income are much lower. The upward trajectory of the curve did not really start until 1950. The increase in the steepness of the curve has been particularly strong since the year 2000.

In 1950 all the nations in the Populous 12 had levels of per capita GDP much lower than the Wealthy 12, with Mexico, being the highest at $4,179, and China being the lowest at $637. By 2016, all but Ethiopia and Congo had surmounted the level of Mexico in 1950. Some experienced long, slow economic growth with some important dips – Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, Iran and Egypt. Other nations saw spectacular growth after 1980, with China being the premier example.

Even some of the laggard nations within the Populous 12 experienced a transformational change in levels of per capita GDP. Pakistan quadrupled from $1,258 to $5,223, and Nigeria more than doubled from $1,961 to $5,360. Even Ethiopia more than tripled from $520 to $1,635.

Unfortunately, the fact that four of the Populous 12 are oil-exporting nations gives a distorted view of their actual economic growth. Many of these nations made far more money from exporting oil than from other products. And the profits from oil exportation tend to go to politically connected elites, so it is unclear how much this economic growth in oil-exporting nations actually benefitted the masses.

The only nation among the Populous 12 that fits the idea of the “poor getting poorer” is civil-war-ravaged Congo, which declined from $1,641 to $808. Obviously, the Congo has not experienced anything like progress over the last few generations. If most nations had such low and declining levels of per capita GDP, this would clearly invalidate the progress hypothesis. Fortunately, very few nations have experienced such declines.

The pattern for the Bottom 20 nations is quite different to the previous two groups. Economic stagnation persisted in those countries until around 2000. Unfortunately, we have no data from before 1950, but there is every reason to believe that levels of per capita GDP among the Bottom 20 nations were very low.

There were some very slow increases in per capita GDP before 1970, but then that progress was erased in the following three decades. It was during this period that it became mainstream thinking to see the poorest nations in the world as being trapped in poverty and beyond redemption. At the time, many believed that only wealthy Western nations could experience long-term economic growth.

After 2000, however, even the Bottom 20 began to experience real economic growth, perhaps for the first time in their history. The strongest economic growth was in Burma, which more than sextupled its per capita GDP, and Sudan, which doubled it. The other nations experienced much slower economic growth, while Niger and Malawi stagnated. Only civil-war-torn Congo saw negative growth during this period.

Of course, an upward trend for the past two decades is not a very long-term trend. Whereas it appears that the Wealthy 12 and Populous 12 have experienced long-term self-sustaining increases in their standard of living, it is too early to declare victory for the Bottom 20. Guarded optimism, however, is in order. Based on all the trends that we have seen for other nations, it seems likely that the Bottom 20 are already reaching or ascending the steep section of the exponential curve.

Exponential growth is even more obvious among the Transformative 16. Those nations all experienced rapid economic growth since 1950 after having suffered millennia of stagnation. This should not be surprising given that this group was selected because of their high levels of per capita economic growth over a long period of time.

The changes among the Transformative 16 are stunning nonetheless. In 1950 the wealthiest nation was Ireland, which had a per capita GDP of $6,983. This made Ireland one of the poorest nations in Western Europe.

By 2017 all the nations in the Transformative 16 had reached levels higher than Ireland had in 1950, except India, which was just below that level. Most of the Transformative 16 had per capita GDP six times what Ireland had in 1950.

Given that some of these nations are some of the most populous in the world, this is a stunning transformation. Virtually all of the nations in the Transformative 16 had levels of per capita GDP that greatly exceeded the levels of the Wealthy 12 in 1950: only India was lower with Indonesia and China at their level. And given the current trajectory, there is every reason to believe that rapid economic growth will continue in the future.

Of all of the metrics used in this study, per capita GDP is the one that leads to the most varied outcomes. Despite this, there was clear progress throughout the world. About half the nations experienced strong economic growth that transformed their people’s standard of living. A handful of oil-exporting nations experienced economic growth that may not have affected their people positively. And the Bottom 20 saw nothing but stagnation until 1990 and then started to experience economic growth afterward.

Other metrics of progress

The metric used in this post is not the only evidence of progress. You can also find evidence for progress in the metrics of economic growth, human development, freedom, slavery, poverty, agricultural production, literacy, diet, famines, sanitation, drinking water, life expectancy, neonatal mortality, disease, education, access to electricity, housing, violence, and happiness (to name just a few), and in virtually every nation. You can find many more in my first book.

Stay tuned for more excerpts…

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See more articles on Evidence for Progress:

Book review: "Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know" by Bailey & Tupy

Long-term trends in per capita GDP (article; podcast; video)

Growth in per capita GDP (2012-2022) (article; podcast; video)

United Nations Human Development Index (article; podcast; video)

Does material progress lead to happiness? (article; podcast; video)

more.

Where is Italy?