The historical significance of the Industrial Revolution in Britain

And why even economic historians often miss it.

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

This article is party of my series of articles on six major breakthroughs that spread material progress throughout the globe:

The emergence of Commercial societies in Europe about 800 years ago that innovated four of the Five Keys to Progress (productive agriculture, trade-based cities, decentralized power, and export industries).

The diffusion of Commercial societies from Northern Italy to Flanders and then to the Netherlands and finally to Southeast England.

The migration of Europeans to much of the rest of the world. The migration of peoples from Britain to North America was particularly important.

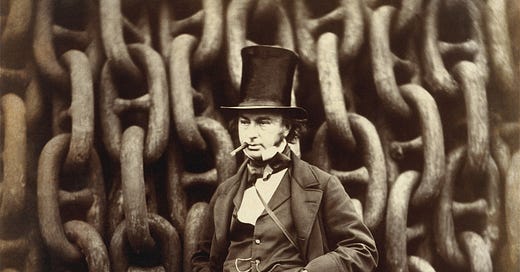

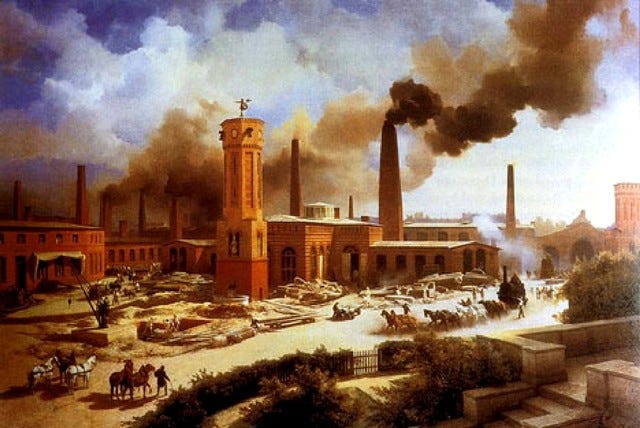

The Industrial Revolution in Britain (this topic of this article), which added the fifth Key to Progress (widespread use of fossil fuels). The Industrial Revolution involved the application of fossil fuels to transportation, communication, materials, agriculture and other technologies, increasing their usefulness. This dramatically increased the rate of innovation to a level where real progress could take place in Western Europe and North America.

The Allied victory in World War II, which ended the totalitarian threats of Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and Fascist Italy. Once the economies of Western Europe and Japan recovered from the devastation of the war, they grew at an unprecedented rate for almost 30 years.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s (the topic of this article), which ended the last of the great predatory empires and undermined the legitimacy of centralized political monopolies. As a result, country after country dismantled totalitarian and authoritarian regimes in favor of increased freedom, democracy, market-based competition, and global trade.

Industrial Revolution

In previous articles in this series, we have seen how Commercial societies in Northwest Europe created the first self-sustaining economic growth that led to real progress for the masses. They did so because they possessed four of the Five Keys to Progress (productive agriculture, trade-based cities, a decentralization of power, and exporting industries).

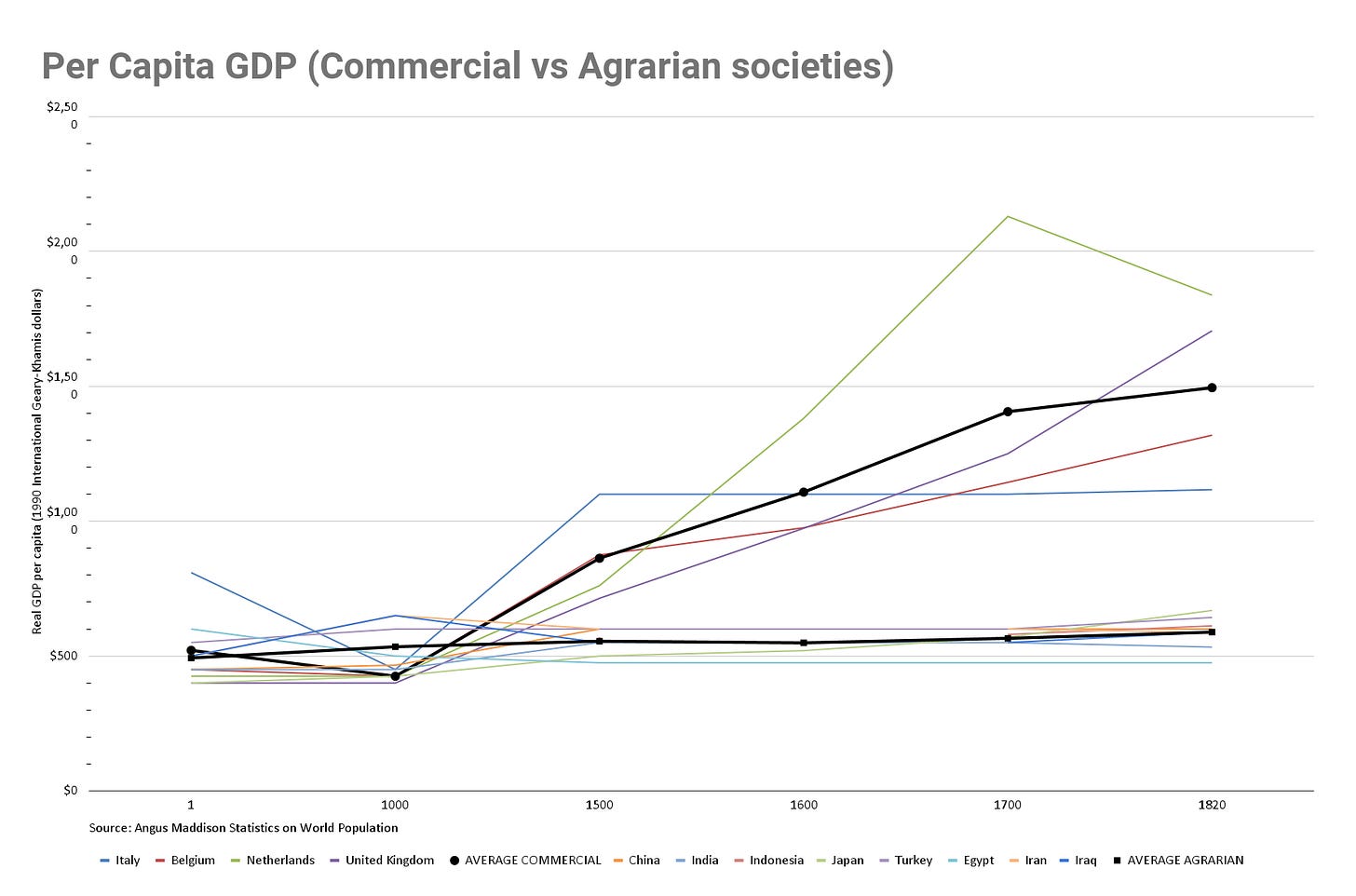

But the lack of the fifth key – widespread use of fossil fuels – placed a fundamental cap on how far that progress could continue. The Dutch Republic in 1670 with a per capita GDP of $2,130/year appears to have hit this cap, as it was not able to break this level for another 160 years.

It was not for another 176 years that another nation was able to break through this limit (the UK in 1846). What followed was another 180 years of economic growth and still counting. Most importantly, this economic growth spread beyond a relatively small network of Commercial societies to encompass much of Europe and North America.

The United Kingdom achieved this result by pioneering a new society type: the Industrial society. The Industrial society is very similar to Commercial societies in that people acquire their food by selling a skill or product in the marketplace so that they can purchase food within that same market. The key difference is that the United Kingdom combined this with the widespread use of fossil fuels.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This article is part of my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

The significance of the Industrial Revolution (this article)

How the Industrial Revolution upset the military balance of power

How Progress shaped the Great Power conflicts of the 20th Century

Industrial technologies

Key technologies enabled Industrial societies to do the following:

Exploit the awesome energy density of fossil fuels

Dramatically increase the productivity of agriculture (using tractors, nitrogen fertilizer, etc.)

Build technology that is so cheap that even the poor can afford to purchase it (using assembly lines)

Transport people and goods rapidly, cheaply, and across long distances (using railroad, steamships, automobiles, airplanes, and container ships)

Communicate across long distances (using the telegraph, telephone, radio, television, mobile devices, and the internet).

Develop new materials and mass produce them for sale (steel, concrete, asphalt, glass, and plastic)

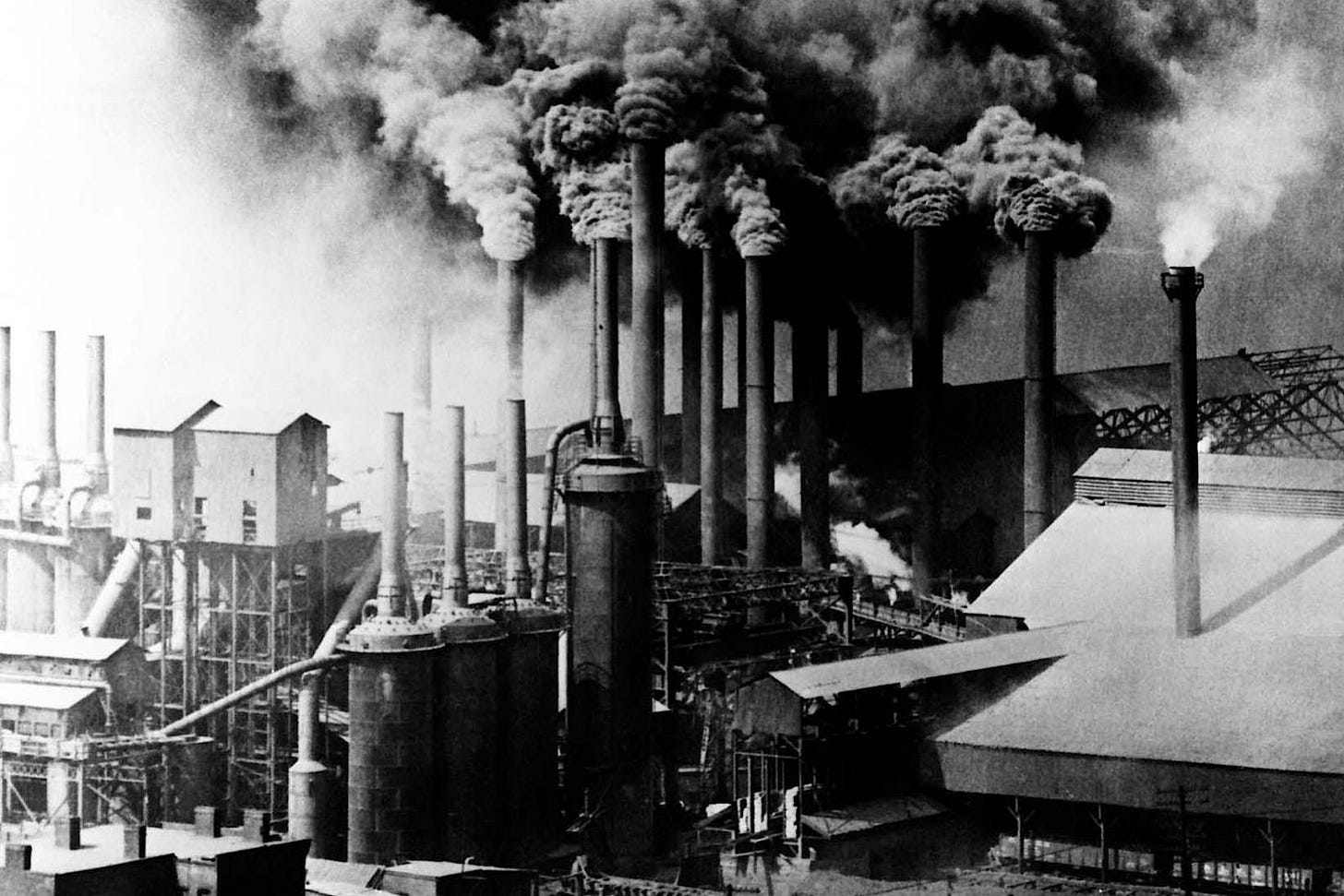

None of this would have been possible without the widespread use of fossil fuels.

In pre-industrial societies, the vast majority of useful energy was derived from human muscle power, animal power, burning wood, or harnessing water or wind. All of these power sources ultimately derived from the sun. Industrial societies added on energy derived from fossil fuels, primarily coal. In the later phases of the Industrial Revolution, petroleum and natural gas played important roles.

The use of fossil fuels injected a huge amount of useful energy into Industrial societies. They found new ways to apply this energy to transportation, communication, materials, and agriculture. The railroad, steamship, factory, electrical grid, telegraph, radio, steel, nitrogen fertilizer, automobiles, trucks, container ships, and airplanes are just a few of the innovations that helped to sustain progress.

Pre-industrial coal use

As an aside, it is important to note that the use of coal for heating homes was common in London and some other English cities long before the Industrial Revolution. To the best of my knowledge, no other society used coal to anywhere near the extent of pre-industrial England (although the Dutch Republic used peat quite widely before the Industrial Revolution).

I do not believe that this undermines my overall argument as heating homes is a specific application of fossil fuels with limited benefits to other sectors of the economy. Warm homes are far more comfortable to live in, but they do not transform societies as the application of fossil fuels to agriculture, transportation, communication, and manufacturing do.

I do believe, however, that pre-industrial coal usage for heating homes gives us an important clue as to why the Industrial Revolution took place in Britain. The use of coal gave Britain critical technologies, skills and organizations that could later be modified and scaled up. While they did not know it at the time, this gave Britain a critical skills advantage over other Commercial nations that might have industrialized earlier.

The Industrial Revolution accelerated existing growth

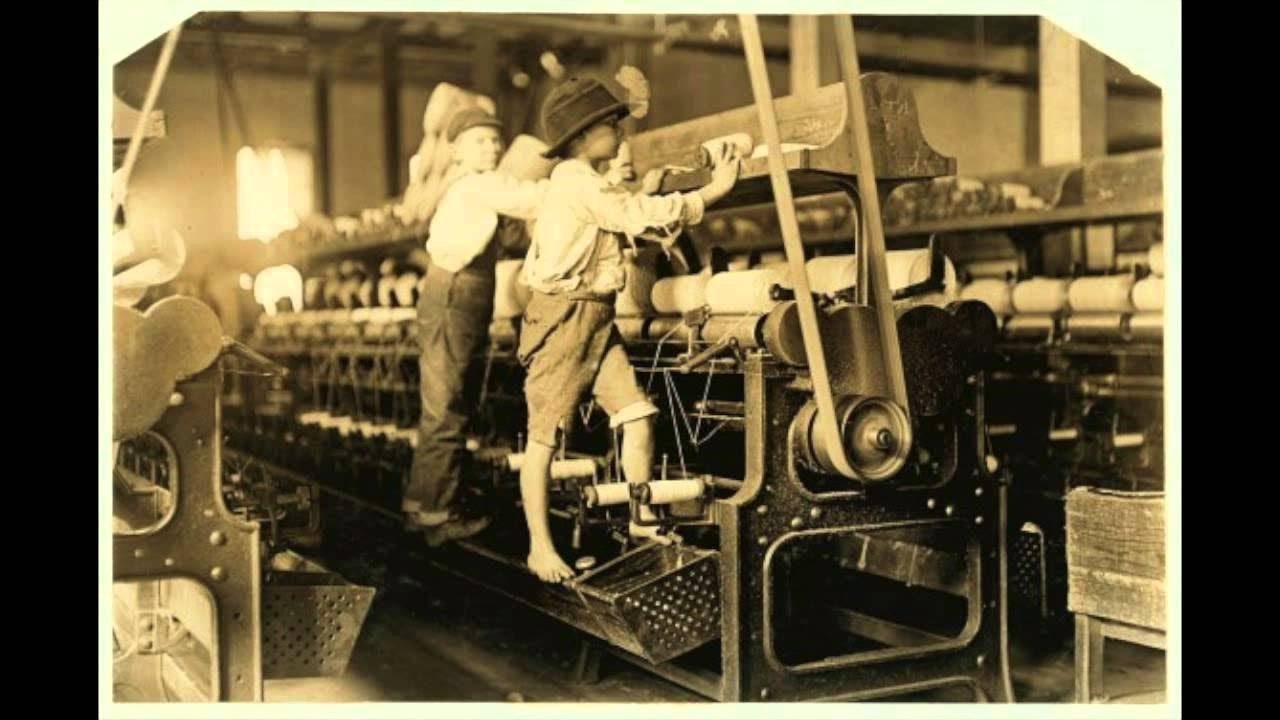

So anyway, let’s get to the main topic. What was the significance of the Industrial Revolution? Most importantly, the Industrial Revolution dramatically increased the material standard of living for the masses. On this point, virtually all economic historians are in agreement.

The most common interpretation of the Industrial Revolution is that it was the beginning of modern economic growth. Most economic historians view the pre-industrial era as having no economic growth that benefitted the masses.

Economic historians typically view the pre-industrial era as being dominated by a Malthusian trap where population growth proceeded faster than the growth of agricultural productivity. They also typically hand wave away pre-industrial economic growth in Commercial societies as merely temporary bursts of growth that were doomed to fail in the long run.

The Industrial Revolution could only happen in a Commercial society

I believe that this Malthusian trap existed, but not for all pre-industrial societies. As we have seen, Commercial societies implemented a farming system that roughly quadrupled food production relative to the Ancient farming system.

Economic historians typically see two large categories of European societies:

Pre-industrial agricultural societies, which include pre-industrial Britain, France, Germany, and Italy (as well as much of Eurasia). These were all caught in the Malthusian trap

Industrial societies with the Industrial Revolution in Britain being the critical dividing line.

Economic historians typically see pre-industrial Britain as not just another agricultural society in Eurasia. Pre-industrial Britain was different from France, Germany, China, and India in many fundamental characteristics. And other societies in Europe at the time shared those same characteristics.

I believe, however, that pre-industrial Britain was a Commercial society.

My view is that there were three types of societies (not two):

Agrarian societies (such as France, Germany, and much of the rest of Eurasia)

Commercial societies which invented human material progress and were a necessary intermediate step before industrialization

Industrial societies, which radically accelerated progress and spread it to regions where it was impossible with pre-industrial technologies, skills, and organizations.

While the traditional interpretations stress what pre-industrial Britain had in common with France, Germany, and Italy, I stress the differences. And while the traditional interpretation tends to ignore Northern Italy, Flanders, and the Netherlands, I focus on those societies.

Pre-industrial economic growth in Commercial societies roughly quadrupled the standard of living from roughly $500 per year to well over $2000 per year. Yes, those Commercial societies were small in population and the cutting edge of economic growth shifted between societies, but this does not diminish this accomplishment.

Most importantly, I see Commercial societies as a necessary precondition for the Industrial Revolution to have happened in the first place. Commercial societies invented many of the technologies, skills, and organizations that were necessary for the Industrial Revolution to take place. So Commercial societies were not some curiosity from history. They were critical to building the economic foundation for the greatest economic transformation in world history.

The Industrial Revolution weakened geographical constraints

The Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom created benefits that were obvious to much of the rest of the world. Industrial technologies, skills and social organizations enable people to overcome many, but not all, of the geographical constraints that previously undermined the possibility of progress.

For the first time, people anywhere on the globe had the opportunity to experience progress. They could now escape the trap of geographical constraints. Those that were successful in copying the UK experienced rapid and sustained economic growth.

In other words, the technologies invented by Britain in the Industrial Revolution were a cheat code that enabled most of the rest of the world to overcome geographical constraints that had limited their economic growth for millennia.

The Industrial Revolution shifted the global balance of power

The economic benefits of progress enabled the British Empire to reach new heights of political and military power. Some nations resented this power, while others chose to copy the technology, skills, and organizations that made it possible.

Commercial Societies copied Britain first

Nations that had previously been Commercial societies found it much easier to copy the UK as they had already built four of the Five Keys to Progress. This makes perfect sense if you believe that Commercial societies were a necessary precondition of industrialization.

Based on Angus Maddison’s historical estimates of per capita GDP:

Belgium’s per capita GDP increased by 67% between 1846 and 1872.

The United States’ per capita GDP increased by 282% from 1850 to 1929.

Canada’s per capita GDP increased by 172% from 1878 to 1913.

Australia and New Zealand experienced even faster growth rates.

Then Free Peasant societies copied Britain

But after Britain invented Industrial technologies that overcame geographical constraints, it now became possible for non-Commercial societies to industrialize. The order in which they did so, however, was closely tied to the type of society they were in the 19th Century.

Nations that had previously been Free Peasant societies were also able to adopt Industrial technologies, skills, and organizations fairly easily. Though they lacked the cities of Commercial societies, their egalitarian social structure, and far more inclusive political institutions gave them a strong foundation to build upon. Based on Angus Maddison’s historical estimates Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway increased their per capita GDP by between 88% and 270% in relatively brief periods.

Agrarian societies were far more resistant to adopting Industrial technologies, skills, and social organizations. The political, economic, and religious elites who controlled extractive institutions saw Industrialism as a potential threat to their power.

There was one domain, however, where the elites could not ignore the effects of industrialization: military power. Industrial Britain had fundamentally disrupted the global balance of power, and the Agrarian powers could not accept the idea of falling too far behind. So in the long run, Agrarian powers were forced to copy British technologies, skills, and organizations that had applications to military power. To do otherwise was to risk military subjugation.

How they did so will be left to a another article.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

This article is part of my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

The significance of the Industrial Revolution (this article)

How the Industrial Revolution upset the military balance of power

How Progress shaped the Great Power conflicts of the 20th Century

The agriculture revolution(s) increased the amount of available energy in the form of calories but did not lead to sustained progress.,

This is because, as he and others point out, that surplus was captured by political and religious elites. It took institutional change for the fruits of progress to be inclusively shared, and as the cities grew, the cauldrons of innovation take hold.

Our ability to harness fossil fuels, essentially stored and compressed solar energy, kicked off the industrial revolution.