How agriculture made Commercial societies flourish

And it happened long before the Industrial Revolution

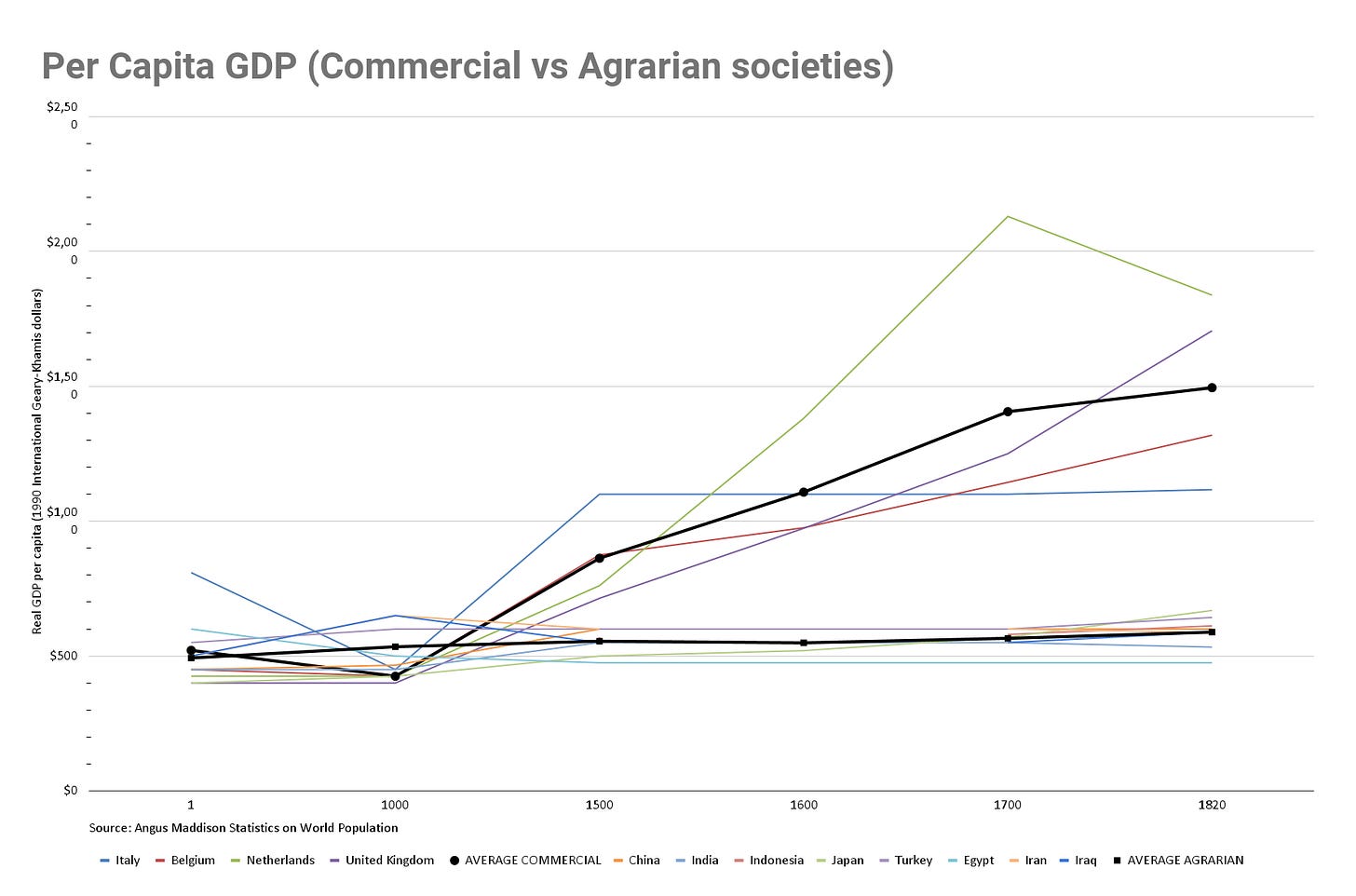

In a previous article, I explained the revolutionary practices that farmers within Commercial societies practiced between 1500 and 1800. In this article, I will explain why they were so important to the economic success of Commercial societies and the founding of human material progress.

I believe that the Five Keys to Progress are the necessary preconditions for human material progress. Four of those five keys were invented by Commercial societies. I will discuss the other three in separate articles.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

Key #1: Productive Agriculture

Food has been the critical constraint on innovation and progress throughout the vast bulk of human history. I know that this fact is very hard for modern readers to relate to, but it is true. Today when we are hungry, we go to the refrigerator or pantry. When the refrigerator or pantry is empty, we go to the grocery store. Easy, right?

Well, no. Not for our ancestors.

While getting enough food to survive is easy in modern societies, it was an epic task for our ancestors. For the overwhelming majority of our ancestors, the quest to acquire enough food to survive took up the majority of their waking hours. It was an obsession, and all of society was organized around the most effective means to do so within the local environment.

Before one can innovate, one must first survive. In order to survive, one must eat large amounts of food. If one has to spend the vast majority of one’s time focused on acquiring food, one cannot devote much time to innovating non-agricultural skills, technologies, and organizations. Our ancestors effectively traded time for food.

The vast majority of mankind devoted the bulk of their waking hours to the quest to produce enough food to eat. Very gradually over time, they innovated new technologies, skills, and processes that enabled more effective means of producing and distributing food. This quest for food production was so all-encompassing that we can categorize entire societies by how they did so.

This quest for food greatly affected where we lived. Until the last few centuries, humans had to disperse geographically in order to acquire food, because the subsistence technology of the day was not productive enough for one family to grow enough of a food surplus to support urban populations. The endless drudgery of acquiring food has stifled the human potential for innovation and progress for millennia.

There is only so much food that can be acquired from any one acre of land with simple technology. With technological innovation, we have been able to radically increase this amount, but for any given natural environment and suite of technologies, there is a fixed amount of food that can be produced per acre.

So humanity dispersed to survive. They had no choice. Survival comes first.

But this dispersal undermined the ability of large numbers of people to interact regularly. Dispersal made it harder to copy technologies, skills, and organizations. With far fewer models to copy, innovation and diffusion were far slower than they could have been.

To make things worse, the type of food that can be produced in any specific area is highly constrained. In some regions, fishing or hunting marine mammals is possible, but not in most areas. In other regions, hunting big game is possible, but not in most areas. In some areas, cultivating rice is possible, but not wheat or corn. In other areas, cultivating wheat is possible, but not other staple crops.

Since food production and distribution is not something that one individual can do, the entire society had to be sculpted around the type of food that could be produced. Technologies, skills, organizations and values of societies were all greatly affected by what type of food could be produced in their geographical environment.

What is more, each one of these food types had very different amounts of energy and nutrients relative to the human work effort. This meant that some societies had huge advantages over others, simply because they lived in regions with the most cost-effective food sources.

Some geographical regions simply could not support much food production, so they doomed their residents to be trapped in poverty. A very lucky few regions were blessed with geography that enabled far more food production per unit of work. These unique geographical characteristics left open the possibility of progress evolving within their borders.

These geographical differences still account for a significant proportion of the inequality between societies that exist to this day.

For thousands of years after the invention of agriculture, our food production systems were deeply unproductive by modern standards. Farmers struggled to support their own families. They needed to store seed for the next harvest, pay taxes to the state and rent to their landlord. They also had to leave half of their land fallow each year.

Traditional farmers lived in a highly uncertain environment where one bad harvest could lead to deaths in the family. They were also under threat from droughts, floods, marauding armies, epidemics, pests and famine. They could do everything right, and then one bad thing happened, and their family was in great peril.

Living in such a situation makes innovation very difficult. The downside of one bad harvest far outweighs the potential benefits of a slightly better harvest. Given their circumstances, farmers were very reluctant to experiment unless they have to do so. As David Grigg has pointed out in The Agricultural Systems of the World, virtually all agricultural systems have been relatively unchanged for millennia. You can read a summary of Grigg’s book in my library of online book summaries.

Fortunately, there was one important exception to this rule: Northwest Europe and the regions settled by Northwest Europeans. While other agricultural systems hardly changed for thousands of years, these regions have undergone many transformations. Each of these transformations resulted in a significantly increased food surplus per family of farmers.

Mazoyer and Roudart sketch out these transformations in exhaustive detail in their book A History of World Agriculture. You can read a summary of their book in my library of online book summaries.

Ancient farmers of Europe and the Mediterranean used a relatively unproductive two-year rotation system along with scratch plows pulled by oxen. Medieval farmers gradually evolved a much more productive three-field system that made use of heavy plows pulled by horses. This likely doubled farm productivity, to a large extent because it reduced fallowed land from 50% to 33% (fallowed land is land that is not planted so the soil can regenerate nutrients for replanting at a later date).

The critical breakthrough occurred when farmers in Commercial societies, such as Flanders (which is now part of Belgium), the Netherlands, and probably Northern Italy figured out how to plant different crops so fallow land was no longer needed. This critical discovery created the food surplus that Commercial cities needed to survive and prosper.

Later, English farmers copied these innovations and invented tools that made the system even more productive. In later centuries American farmers learned how to mechanize and motorize cultivation. This pushed agricultural productivity into the stratosphere.

Agricultural exports to growing cities

We often think of industries being based on metals, fossil fuels, and digital technologies. But early industries were largely based on a wide variety of animal-based and plant-based materials that were reprocessed into final products for consumers. Between 1500 and 1800, there was not a clear divide between agriculture, trade, and industry. They were all tightly bound into one economic system. And what powered that system was the food surplus produced by the Commercial farming system and horse-drawn wagons for connecting the fields to the markets.

For the first time in history, farmers had a substantial and reliable food surplus to sell in the marketplace. And they also had a vast number of horse-drawn wagons. This enabled the rise of Commercial cities where most of the period’s innovations took place. Without these sizable food surpluses, a constellation of dynamic Commercial cities would have been near impossible.

This increased productivity created a food surplus that could be profitably sold to cities. Those that were lucky enough to live near rapidly growing cities had a strong incentive to specialize and export their produce to the cities. In the Medieval system, relatively few crops were exported. Wine and wool were the major exceptions. Now, in areas near commercial cities, a dense web of economic connections knitted together cities and the surrounding countryside for many miles around.

Products that were previously only consumed on the farm could now be exported to the cities. An entire secondary market for agricultural goods came into being. Some of these goods were raw foods for human consumption – beef, pork, mutton, lamb, chicken, milk, eggs, nuts, honey, fruits, and vegetables.

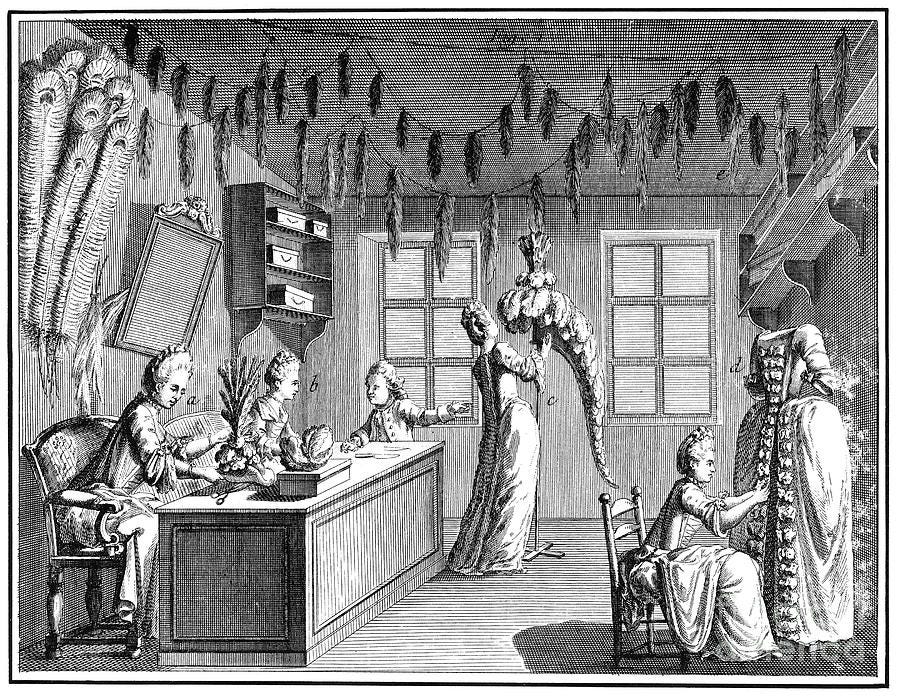

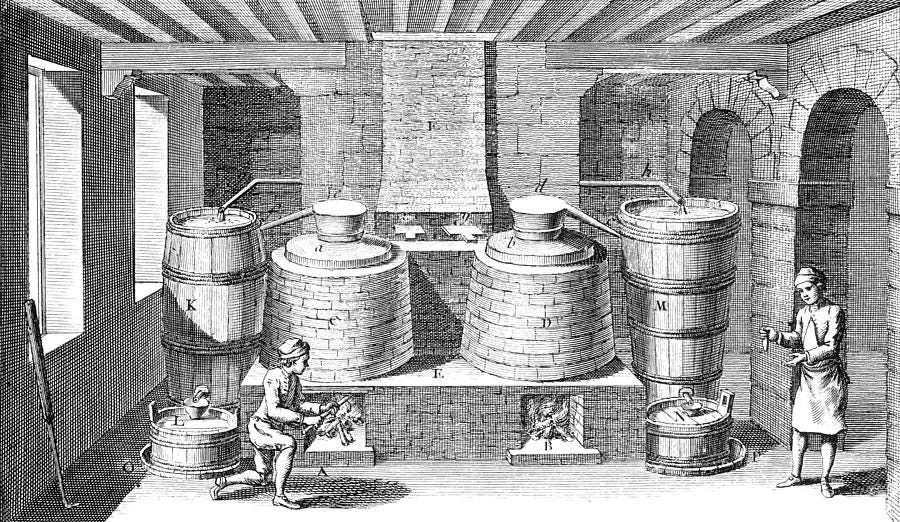

Other agricultural goods were processed for human consumption – oil, cheese, butter, cream, yogurt, beer, wine, whiskey, gin, and rum. Some were goods processed from plants – flowers, woad, hemp, rope, wool, flax, and linen. Others were goods processed from animals – leather, manure, bone, sinew, marrow, feathers and fur.

Some of the goods were processed on the farms, while others were transported to the cities for further processing and sale. Previously, this type of commercialized agricultural exports was limited to wine and wool. Now it had spread to a suite of other agricultural products.

As farmers increased their exports to neighboring cities, some found it more profitable to specialize in one agricultural good. Because it was now far easier to buy food in the market, it was no longer necessary to grow every necessary foodstuff on your own farm. Farmers were now free to focus their time on one product, giving them an incentive to increase their skills, adopt new technologies and techniques, and expand the scale of their production.

This increased specialization of crops enabled the Northern Italian, Flemish, Dutch, and English farmers to do what would previously have been unthinkable: to shift away from growing grain. Because grain was one of the few crops that could be stored and transported over long distances, Flanders found it more profitable to import large amounts of grain from the Baltic.

This grain trade proved highly profitable for Flemish and Dutch merchants. And having the option to buy cheap imported grain gave Flemish and Dutch farmers even greater incentives to shift their production to more profitable secondary agricultural goods.

Secondary agricultural products created enormous benefits to cities as well. With a flood of products that started out as domesticated animals and cultivated plants and were then processed into profitable goods, a radical diversification of urban economies could take place. Entire new professions, skills, and industries sprouted up.

This not only created a wide range of producers, but it also created a large growth in the number of consumers. Each specialized worker in the city had no choice but to buy what they needed on the market. Whereas, they had previously been forced to produce all their own goods, now they were modern consumers who purchased those items on the market.

This created a positive feedback loop that stimulated the expansion of markets. The more city dwellers found it necessary to purchase goods on the market, the more farmers could specialize in the most profitable products. The more farmers focused their skills and energy on these products, the more the price dropped. This stimulated more urban demand, which continued the feedback loop.

Proximity to growing cities also made it more realistic to seek seasonal employment in the cities during times of low labor needs. Since farmers were no longer hovering on the edge of survival, they could afford to seek out the most highly paid non-agricultural jobs. Some of these temporary migrants decided to stay in cities permanently. This constant flow of migrants kept cities growing in population.

The greater variety of foods also enabled both farmers and urbanites to eat healthier and more balanced diets. The Medieval diet was largely restricted to bread and beer. Now meat, eggs, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables could all be consumed in much greater quantities. While it was hardly a diet that modern nutritionists would recommend, it was far superior to the diet of Ancient or Medieval farmers.

While the new no-fallow system created enormous advantages for farmers and urbanites, the system was very slow to spread. Only regions with a large number of cities and widespread peasant ownership of land could realize its benefits. Resistance to change from peasants, nobles, and kings was substantial until the 19th Century.

Only Flanders, Netherlands, Southeast England, Southern Scandinavia, and scattered parts of western and northern Germany and northern France saw a widespread transition to the new agricultural system. As late as 1840, the vast majority of European farmers were still using the same farming system that they had used in 1300. Most of the adoption of the no-fallow system coincided with the Industrial Revolution in the middle and late 19th Century.

So agriculture was not some sideshow to progress. It was and still is one of the key foundations that progress is built upon. Today, we get caught up in flashy innovations on the leading edge of innovation, and we should. Those innovations are very important. But always remember that all of these innovations rest on the toils of the lowly farmer.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

How important would you say the opening of three new (recently depopulated) continents were to the breakthrough in prosperity?

It seems we had four overlapping breakthroughs in agricultural productivity:

1) major improvements in productivity as illustrated by this and your last post.

2) the opening to Western Europeans of an order of magnitude more acreage, currently not being farmed in the Americas, Australia and various large islands

3) the introduction of new and substantially more productive crops (potatoes and corn) to Europe

4) the substitution of forest wood with coal (and eventually the replacement of pastureland for horses with oil for cars)

Fantastic article. Food is energy, we need energy to maintain homeostasis. As you points us, to innovate, first one has to survive.

The key distinction between the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution was the unlocking of fossil fuels, energy that could power our machines and augment human/animal physical capabilities.

What I find interesting is that both were "energy" revolutions, even we do not call them that.