The American System

Henry Clay’s early-19th Century plan to spur American progress and unity

Read more of my articles on American Progress:

One of the main goals of my book series and this Substack column is to propose policies to promote material progress in wealthy nations and developing nations. It is helpful to look back at the reform proposals of previous generations. One of the most important in American history was the American system.

The American system is a forgotten economic and social policy to promote American progress and national unity. The American system combined a belief in market-based economies with economic nationalism, which many people today consider to be opposites.

The politicians most closely associated with the American system were:

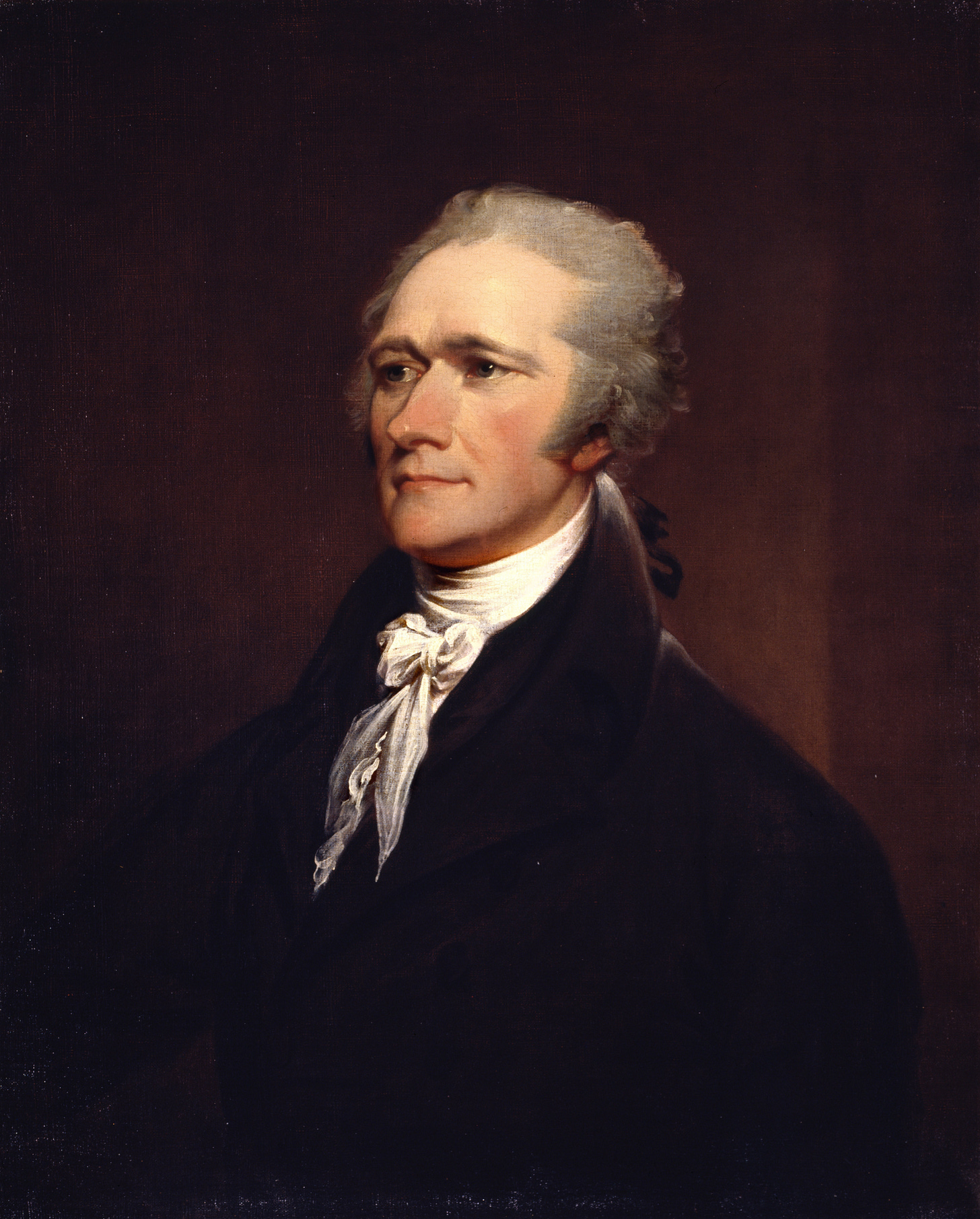

Alexander Hamilton (Secretary of Treasury under President Washington and informal leader of the Federalist party)

John Quincy Adams (Secretary of State and 6th President)

Henry Clay (Speaker of the House, three-time Presidential candidate, and informal leader of the Whig party)

Daniel Webster (US Senator, Secretary of State, and considered to be one of the greatest orators in American history)

Abraham Lincoln (one of the greatest Presidents in American history)

Of all the above, Henry Clay is the one who is most closely identified with the American system. Henry Clay is often considered to be one most successful American politicians to have never become president.

Proponents of the American system believed in market-based economics as Adam Smith, but they also built on the views of Alexander Hamilton that specific government policies could promote:

Industrial development.

Agricultural expansion (both in terms of land area planted and productivity per acre)

National defense (indirectly via economic development and directly via a standing army/navy)

National unity (by building transportation infrastructure to link all parts of the nation together into one market)

More specifically, Henry Clay’s American system was based on the following policies:

A high tariff to:

Generate federal revenue

Protect American industry from British competition

Promote industrialization in cities

Sale of public lands on the frontier to homesteaders to:

Generate federal revenue

Push the population frontier westward

Foster the growth of independent small-holding farmers

Federal investments in “internal improvements,” particularly on the frontier:

Roads

Turnpikes

Railroads

Canals

Ports

Navigation improvements on coastlines, rivers, and inland waterways

Establishment of the U.S. bank (something similar to the modern Federal Reserve) to foster commerce.

Many supporters of the American system also proposed:

Promoting agricultural research to promote farm productivity.

A standing professional army.

Constructing a frigate-based standing professional navy

Government support for science, technological innovation, and public education.

Maintaining a strong legislature in the face of growing presidential power.

In general, the Whig party and the Republican party supported some form of the American system, while the Democratic party opposed it as an unconstitutional expansion of federal government power. Because the Democrats dominated federal politics from 1832 to 1859, the Whigs were unable to implement much of their agenda on the federal level. Some Whig-dominated state legislatures, however, managed to implement elements of their program on the state level.

While very important during their time, the Whig party always seemed to come up on the losing side, even when they won elections. The Democrats typically had working majorities in Congress, and Whig presidential candidates had a nasty habit of dying early in their terms and then being succeeded by Vice Presidents with very different views.

The first Whig president, General William Henry Harrison, died just 31 days in office

The second Whig president, General Zachary Taylor lasted just over one year in office.

This meant that the increasingly pro-slavery and successionist Democratic party dominated the federal government during the critical 1850s.

As most students of American history know, the Whig party was fatally divided on the issue of slavery. Because the Whigs believed in both individual rights and national unity, they found it very hard to balance the two. In the general, the party was divided between:

Conscience Whigs in New England, who morally opposed slavery. While rarely abolitionists, they favored using federal government power to stop the expansion of slavery into the territories.

Cotton Whigs in the South and New York City (where cotton textile industries were located) who increasingly favored slavery and state rights.

The American system was adopted almost wholesale by the fledgling Republican party when it formed in 1854. The Republican party fused anti-slavery instincts with the economic and social policy of the American system. Most of the American system was finally implemented by Abraham Lincoln and the Republican party during the Civil War when Southern Democrats had no congressional representation. The specific legislation included the:

Morrill Tariff Acts of 1861 and later years

Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act of 1862

Homestead Act of 1862

National Bank Acts of 1863 and 1864

Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864

And, oh by the way, Lincoln and the Republicans also won the Civil War and freed the slaves too! Not bad for four years work…

The following period between 1865 to World War I was perhaps the greatest achievement of material progress in world history up to that time. Not only did the United States experience per capita growth rates that were probably higher than any other society, but they did so with rapidly growing populations.

Given the importance of agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation infrastructure to economic growth in general, it is difficult to believe that the implementation of the American system did not play an important role in this outcome. The only thing that was missing from the American system was an appreciation for the importance of energy, particularly coal.

Tariffs

The part of the American system that was most fully implemented in federal policy was protective tariffs. While the economics profession today is strongly against tariffs, it is hard to ignore the fact that many nations that successfully industrialized had protective tariffs on those industries before and during industrialization.

In the 19th Century, the United States had very high tariffs, particularly on manufactured goods. Tariffs hovered around 40-50% during the Republican-dominated period between 1860 and 1912. The purpose was to protect fledgling American manufacturers from more established British competition. While it is impossible to prove causality, it is clear that high tariffs did not undermine economic growth.

It is important to keep those tariffs in the proper context. The northern half of the United States was already a dynamic Commercial society. This was caused by a combination of:

geographical factors as well as

a massive domestic market that enabled manufacturers to be less dependent on foreign exports.

This made it relatively easy for the United States to copy the Five Keys to Progress. In such a situation, protective tariffs probably greatly assisted industrialization. Without those tariffs, it is quite possible that the United States would have focused on exporting agricultural goods as Australia and New Zealand did.

I seriously doubt, however, that those same levels of tariffs would have led to similar results in other nations. You cannot simply impose tariffs on a stagnant economy and expect them to create a dynamic export industry. Other policies are necessary to do so in most developing nations, though targeted tariffs may play come role.

Note also that once the United States established itself as a dominant manufacturing exporter, tariffs went way down. Other nations, such as the UK and Germany went through a similar transition.

Homestead Acts

There is strong reason to believe that if the federal government did not support homesteading, American history would have been very different. The United States could have followed the Roman model and given all arable lands in the territories to politically influential families. This would have created a massive imbalance of land ownership just as the Roman Republic did. This is both bad for society and leads to unstable politics. If the Roman Republic had a Homestead Act, its history might have been very different.

It seems doubtful that the productivity of American agriculture would have grown so rapidly if the vast majority of arable lands in the Midwest and West were owned by wealthy absentee landowners. And certainly, politics would have been much different. Homesteads also enabled poor urbanites and immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia to establish thriving farms rather than languish as unskilled laborers in the cities.

The Homestead Act clearly played an important role in enabling:

Westward expansion

Relatively egalitarian distribution of arable land in the territories

Expansion of agriculture productivity

Massive exporting of grain to Northeastern cities and Europe

Growth in trade-based cities in Midwest

Stable politics in those states

Again, the Homestead Acts must be put into proper context. It is extremely rare in history for a government to have access to millions of acres of arable land. Even if other nations would have wanted to duplicate those policies, they would have virtually no arable land to sell.

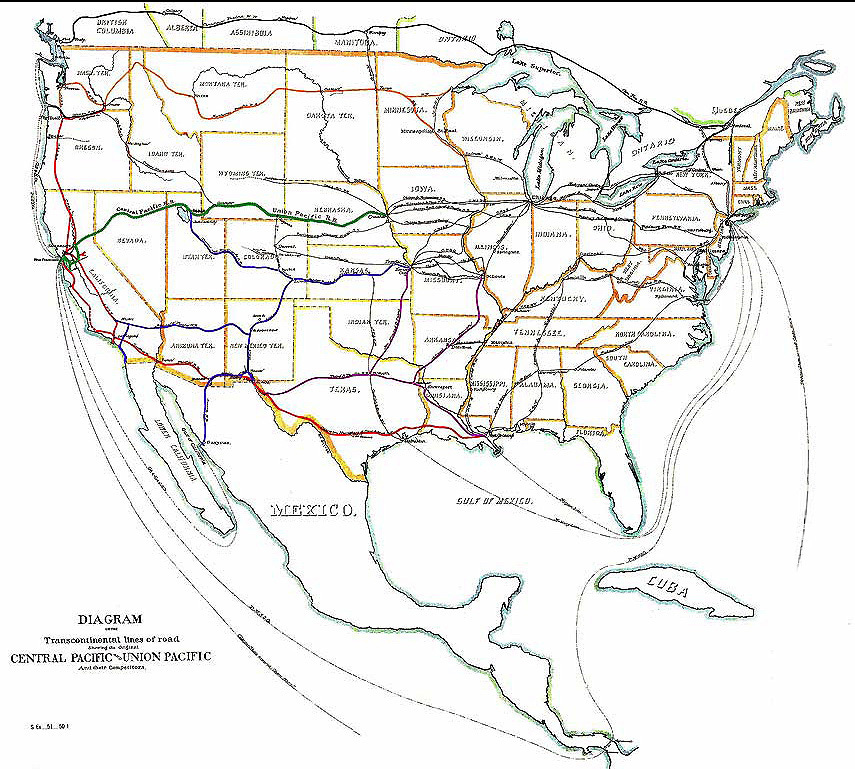

Transportation infrastructure

I do not think there is much doubt that massive investments in transportation infrastructure, particularly on the Western frontier, played a major role in American economic growth in the late 19th Century. Roads, canals, bridges, railroads, and ports were essential to American economic growth in the late 19th Century. Much of this was paid for via private investment, but government investment played a significant role, particularly on the frontier.

Transportation infrastructure:

Opened up new domestic and overseas markets for Midwestern farmers, giving them the incentive to adopt the most productive technologies and practices.

Enabled Midwestern farmers to get the necessary tools and agricultural inputs.

Tied together trade-based cities in the Midwest and Northeast to the agricultural hinterland. Chicago and New York City were the most important, but a constellation of smaller cities also played an important role.

Enabled the extraction and distribution of coal and petroleum.

Enabled far more regions to experience economic growth.

Enabled military forces far greater strategic mobility and the logistics to remain in the field for long periods of time.

In theory, private investors could have done this, but they had an incentive to wait and see where demand would grow. The federal and state governments could invest in transportation in the sparsely populated Territories and regions with sluggish economic growth to create that demand. With a massively growing population, the idea of “invest and the demand will come” made far more sense than it does today.

Avoiding the Civil War

The period from 1830 and 1860 is dominated by the specter of the American Civil War. Though historians should always try to look at a period without too much focus on later events, it is very hard to do so in this period. This leads to an interesting question:

If the Whigs had fully implemented the American system on the federal level in the 1830s, 40s and 50s, could the Civil War been avoided?

Of course, it is impossible to answer this question, but I do think that the answers pivots around the psychology of large slaveholding plantation owners who dominated the Democratic party in the Deep South. If the American system had been fully implemented in the 1830s or earlier, it might have persuaded the large white slaveowners that:

Industrial development was in their long-term interest and

Slavery was fundamentally incompatible with that industrial development.

Prior to 1830, most Southerners viewed slavery as a necessary evil that was bound to expire at some point in the future. It was only after 1830 that the idea of slavery as a positive virtue that must be defended and expanded emerged. A dynamic and growing Northeast and Midwest knitted together by a vast transportation infrastructure would have grown around and isolated the Deep South.

Unfortunately, we will never know the answer to that question…

Read more of my articles on American Progress:

I will have to disagree with you here on tariffs. They do not appear to have impacted growth early in American history because while trade of goods was restricted, the borders for immigrants were virtually open. The influx of labor made up for the high tariffs as the population exploded from 5 million in 1800, to 75 million in 1900.

Optimally, growth would be fastest with open borders and free trade, but we can often get by with one or the other. What we cannot do, however, is throttle both imports and immigration at the same time.

Could the South have tried to industrialize with slavery?