Understanding Class in American society

Most discussions of Class are not useful

Make someone’s day: Gift a subscription to your friends and family!

My first two books and this Substack column have primarily focused on progress of entire societies. In particular, I have focused on the:

The Five Keys to Progress, which I believe are the necessary preconditions of human material progress. When those keys are achieved, the society transforms into a vast decentralized problem-solving network that generates progress.

How Progress Works, which explains day-to-day human behaviors that create progress once those keys are achieved.

It is important to understand, however, that just because a society experiences long-term economic growth, this does not mean that all people within that society share the benefits of that growth. So I think that something important is missing if one focuses exclusively on entire societies. In particular, one needs to focus on those who have less in wealthy societies. How might their needs to addressed?

The typical answer from the Left is to expand government social programs and regulations to help create a more egalitarian society. I believe that this strategy has reached a natural limit, particularly in Europe, where the economy has been stagnant for 15 years and government spending takes up roughly 50% of the economy. It is difficult to see how government social programs can be expanded any further.

Progress + Upward Mobility

There is, however, another strategy. Rather than redistribute wealth, we should be trying to create wealth and enable a greater portion of the people benefit from that growth. We need a Progress-based reform agenda focused on the following principles:

Create a prosperous working class.

Promote a clear pathway that enables youths from low-income families to enter the prosperous working class.

Focus relentlessly on results; experiment in a controlled way; do more of what works; do less of what does not work.

Reform the political process to make all the above possible.

I sum up goal #1 as “Promoting Progress” and goals #2 and #3 as “Promoting Upward Mobility.” I focus on goals #1, 4, and 5 in my book: Promoting Progress: A Radical New Agenda to Create Abundance for All. In my forth-coming book, Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda for Uplifting the Working Class and Poor, I focus on the second and third goals.

While I have argued that Equality is impossible to achieve, I believe that Upward Mobility is an achievable goal. While Progress is an increased material standard of living for the society, Upward Mobility is the increased material standard of living for the individual.

To fully understand the challenges of promoting Upward Mobility, I think it is important to understand “class” in American society. I believe that most uses of the term “class” are not very useful because they use the wrong demographic characteristics to identify class categories. Worse, they lead to the wrong conclusions about how best to assist the lower classes achieve Upward Mobility.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Defining Class Categories

There is no generally agreed-upon definition of class, how many classes there are, and how each of them is defined. This is not surprising given how controversial the concept of class is and how closely tied it is to ideology. Typically, when journalists write about class, they write exclusively about “the middle class.”

In defining the middle class, journalists or social science researchers typically pick an income range with an upper and lower limit – for example, everyone with incomes between $50,000 and $100,000. This is an enticing method to measure class because it is simple and easily understandable to readers. Income also directly translates into the ability of a person to purchase products or services that directly affect one’s material standard of living.

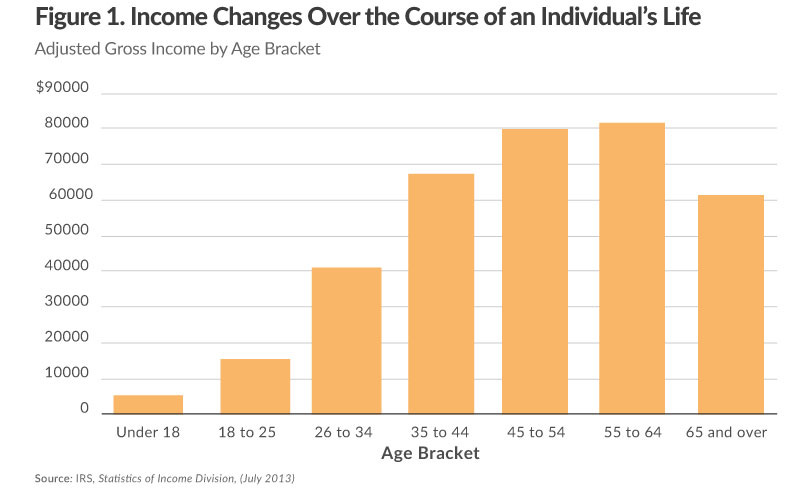

Unfortunately, using income to measure class is very misleading. Few people realize how much an individual’s income varies throughout one’s lifetime.

In general:

People in their twenties earn very low incomes, regardless of their class.

As they gain skills and acquire work experience, their income gradually increases until sometime in their 50s.

Then their income drops dramatically when they decide to retire. For most people, retirement occurs sometime in their 60s.

For this reason, our definition should focus heavily on those between the ages of 30 and 65. Persons below age 30 and above age 65 have incomes that more closely reflect the material standard of living over the course of their lives. This is not true for those under age 30 and over age 65.

You are reading an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda for Uplifting the Working Class and Poor. The remainder of this excerpt is only available for paid subscribers.

It is very common, for example, for a twenty-something college graduate with a four-year degree to work in a restaurant or retail store and barely earn above minimum wage. According to an income-based definition of class, such people would be “poor” or “working class” depending upon the preferred terminology. But realistically everyone knows that the fact that the person earned a 4-year college degree puts them on a very different long-term income trajectory.

It is also very common for working-class men to earn a relatively high salary while in their 50s. This is particularly true if they are unionized production workers who typically get pay raises based on seniority. While that person earns a high income, far higher than our hypothetical twenty-something college graduate, few people would say that this middle-aged factory worker was in a higher class. Income matters, but it cannot be used in isolation.

Even these changes throughout a lifetime do not capture enough of the variation:

Most people go through at least some period of being unemployed.

Many people go through significant periods when they voluntarily work fewer hours per week to care for children or elders, due to health issues or to enroll in education or job training.

Many people sell a house and then are required to report the capital gains as part of their income. This makes their incomes in that one year appear far higher than their income over a longer period.

For the vast majority of people, these life events lead to short-term variations in income, but they do not lead to a change of class. All of these examples show why income is not a useful means of measuring class.

Key Demographic Factors

So we need a means of measuring social class that is far more stable than income. I propose a radically different method, which I believe helps us to understand the ramifications of choices that people make, particularly in their youth. I believe that it is most useful to divide Americans up into five classes, based on the following four criteria:

Age

Education (particularly those with a four-year college degree and those that do not)

Work status (whether a full-time worker is in the household)

Marital status

When I break down American households based on these critical characteristics, I get something that looks like this. I will discuss this diagram in more detail in upcoming articles, but for now, I want to explain the characteristics of each group:

The Professional Class

At the top of the American class structure is what I call the “professional class.” Because these people are in the class that ranks highest in terms of income, wealth, and social status, I will also sometimes refer to them as the “upper class.”

The central defining characteristic of the American professional class is that its members have earned a 4-year college degree. Many professionals have also earned a graduate degree. While someone can acquire employment as a professional without a 4-year college degree, it is becoming increasingly rare.

The other important characteristic of the professional class is that they have at least one full-time worker in the household. Single professionals invariably work full-time, while married professional couples often have two incomes. Without working, professionals cannot leverage their 4-year college degree into income and wealth. Of course, some are temporarily unemployed or voluntarily take time off, but this is almost always a short-term deviation from the norm.

Notice that I said “one full-time worker in the household.” It is not at all unusual for married professional women with young children to drop out of the workforce to take care of their children full-time. Doing so does not change her class status because she still has a full-time worker in the family. In theory, a married family can have two part-time workers in the family which combine to achieve a “full-time equivalent,” although this is rare.

The third characteristic of the professional class is that they are between 30 and 64 years of age. In other words, they are:

old enough that they have established their careers, but

they are not so old as to be retired.

Persons over age 65 are typically retired, while those under age 30 are just starting their careers and have not yet mastered the necessary skills to generate a high income. So many twenty-something persons with 4-year college degrees temporarily work in non-professional jobs that pay poorly that including them in the professional class would be misleading.

Working Families

Our second class is what I call “Working Families” or the “Working class.” Some might call them “middle class,” but I think the term “working families” is far more descriptive and accurate.

Working Families have the same age criteria as the professional class, 30–64 years old, for the same reasons. Persons over age 65 are typically retired. Persons under age 30 are just starting out. Working families also have at least one full-time worker in their household.

What distinguishes working families from the professional class is primarily their level of education. Working families have at least a high school degree and some have attended some form of college, but they do not have a 4-year college degree. They might have an associate degree, or certificate or have attended some college without graduating. Their lower levels of education place working families on a fundamentally different lifetime earning trajectory from professionals.

The final criterion for admission into working families is marriage. Most people do not think of marriage as important to class differences, but marital status is a critical distinguishing factor between working families and the lower class.

For Americans without a 4-year college degree, marriage is a fundamental bedrock for their financial survival. While single professionals have the earning power to prosper without marriage, a high school degree by itself does not lead to high enough earnings to achieve prosperity.

Marriage enables working families to have two incomes instead of one. It also gives working families a stable platform to raise children. Marriage and children also give working-class men a reason to keep working hard in jobs that are often not as personally fulfilling as the typical professional-class job. Unmarried men are far more likely to drop out of the workforce, undermining their long-term economic success.

Lower Class

The third class is what I call the “Lower class.” I am sometimes use the term “Lower-income,” but some members have no earned income at all. I deliberately do not use the word “poor”, because many of these people are above the official poverty line and spend more than the official poverty line. In particular, the vast majority of the Lower class are not poor in comparison to the rest of the world or societies in history.

As with our previous two classes, the lower class has an age criteria of 30-64 years old. What causes a person to be in the lower class is an absence of the factors that lead to entry into the professional or the working class.

Lower-class persons are missing one or more of the following:

High school degree

At least one full-time worker in the household

Marriage.

In general, the more of the above factors that a person is missing, the greater the chances that a person will fall into the lower class. While it is not necessary for entrance into the lower class, a key distinguishing factor in income for the lower class is a dependence on benefits from government social programs for a high percentage of consumption.

Any household that does not have a full-time worker (or a combination of multiple part-time workers that add up to at least 35 hours of work per week) is very unlikely to have much of an income. Of course, some members of both the professional and working classes are temporarily unemployed, the lower class often exists in that state for years or decades.

While the professional and working classes receive very few direct government subsidies, a substantial portion of lower-class income is derived from means-tested programs. One might say that the principal purpose of the means-tested programs is to give the lower class a more comfortable standard of living.

One characteristic of the lower class that is surprising to most people is that their expenditures vastly exceed their income. About 71% of all earners in the bottom 20% of incomes consume more than their income. In 2005, for example, consumption was on average double their income (Eberstadt 2008 p36-41).

So official income statistics vastly understate the actual standard of living of people with low incomes. This, by the way, is yet another reason why income should not be used to judge a person’s class or standard of living.

Unfortunately, our data is too limited to fully understand how lower-income persons can consistently spend more than they earn.

Many of them are only temporarily in this status, so they are spending their savings

Many are earning means-tested government benefits

Some are underreporting income to avoid paying taxes and to remain eligible for means-tested benefits

Some even live off the earnings of criminal activity.

Regardless of how the lower class can consume double their income, it is clear that it is not a pathway toward a successful and happy life.

Retirees

The fourth class is what I call “Retirees.” I define retirees as anyone who is 65 years old or older. There is some variation in the age when individuals retire, and some retirees work part-time jobs to supplement their income. The critical factor is that they have chosen (though not always 100% voluntarily) to stop working full-time and they are eligible for Social Security and Medicare.

While most people do not think of retirees as a class, it is very important to conceptually separate them from the three previously mentioned classes. Because retirees do not work full-time, they often have very low incomes.

The vast majority of retirees:

Qualify for Social Security and Medicare or live in a household with another person how does.

Typically own a house, and the vast majority of retired homeowners have paid off their mortgages. This greatly reduces their living expenses.

Many retirees also have pensions, savings, or investments.

Retirees also do not have to spend extra money on clothes, daycare, and transportation as those in the workforce need to do. In short, while they typically have low incomes, retirees tend to have average or above-average standards of living. And their income is not tied to employment, so they have far more free time.

I fully acknowledge that there is great economic diversity within this group. Some have tens of millions of saved investments, while others are eeking by on Social Security alone.

My main purpose in identifying “retirees” as a class is to separate them from the other three main classes. Retirees already get a large amount of help from the government via Social Security and Medicare. It is not clear that doing more will promote Upward Mobility.

A common mistake that is often made in analyzing class or inequality in American society is to fail to exclude persons over 65 years of age. This inevitably leads to misleading statistics as the actual standard of living of retirees is far higher than their income would suggest.

Youths

A worse mistake in analyzing class and inequity is to fail to separate youths from adults over the age 30. Youths, which I define as persons aged 18-29 typically have very low incomes. But this low income does not mean that all youths are doomed to low-income trajectories throughout their life.

It is best to think of youths as “just starting out.” Unlike other classes, their current situation is likely very different from their long-term material standard of living. They are however making decisions that will have a substantial impact on their long-term material standard of living.

I remember when I was in my twenties. Through almost all of my twenties, I made well under $20,000 per year. And many of those years I made much closer to $10,000 per year.

I really thought that this was my future, and the good times that my parents lived through had long since passed. Fortunately, during that period I made some wise life choices, and my material standard of living increased dramatically in my thirties. I also married a wonderful woman, and we built a nice life for ourselves and our children.

While I feel fortunate, my situation was not unusual. Employers pay their employees based on their experience and skills. Typically, young people have relatively low levels of both. If they keep working and mastering skills that are desired by employees, youths can rapidly increase their income as they enter their thirties. While their income denotes youths as being poor or near-poor, it is far more useful to think of them as “just starting out.”

The very different characteristics of young people and retirees compared to people aged 30-64 show how misleading it is to look at the overall income distribution. A person with a specific income who is 25 years old has a very different standard of living and future income trajectory from someone making the same income at age 50. The same is true for a person with the same income at age 70. Age has such a powerful effect on income and standard of living that it always must be considered first.

Some people fall into the cracks

Now I do not pretend that my class categories are perfect. In creating these categories I was trying to:

Create as few categories as possible

Using demographic variables that are easily accessible and have a demonstrated effect on long-term standard of living

While capturing varying life outcomes

Clearly, my class categories do not fully account for every American. A fair percentage of Americans over 30 years old do not clearly fall into one of these four categories.

Some unusually mature or talented persons under age 30 make life choices that enable them to enter the professional class or working class

Some people with 4-year college degrees do not get married or have a full-time worker in their family. These people typically have the beliefs of the professional class but with substantially lower incomes.

Some people without 4-year college degrees, such as actors, musicians, athletes, and entrepreneurs, become amazingly successful in their careers.

Some people develop serious healthcare issues or disabilities which cause downward mobility.

Some people retire much earlier than age 65, and some never retire at all.

Some people live in far more prosperous regions than others do.

People of different classes often intermarry, although this is becoming increasingly rare.

Despite these categorization problems, I think my method of viewing American class is very useful. My categorization is meant to create a deeper understanding of the key criterion that determines which class a person belongs to. In particular, I want to focus on age and marital status as they are critical criteria that are missing from most analyses. And I also want to show why income is not a particularly useful means of looking at class.

See more articles on Upward Mobility:

I also will be writing a significant number of excerpts from my forthcoming book: Upward Mobility: A Radical New Agenda to Uplift the Poor and Working Class. Most of these excerpts will only be available to paid subscribers.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

This is a really useful framing of the issue.

On mobility, isn’t that determined more by movement between categories than by individual increases in income?

What determines distribution of wealth? That's a question no one asks yet, distribution of wealth should be taught before creation of wealth