Did the British Industrial Revolution occur in the 17th century?

A new study comes to conclusions that may surprise many

A very interesting study regarding the timing of the Industrial Revolution in Britain was recently released by the University of Cambridge. You can read a short summary here. The study was based on the Economies Past database. As they summarize on their website:

“Over the last 20 years, a team of historians at Cambridge have collected millions of records to build, for England and Wales, the most detailed quantitative picture of long-run economic development ever assembled anywhere in the world. The data concern occupational structure, which refers to the distribution of men and women through different economic activities.”

Let me start by saying that I am very enthusiastic about these type of databases. I tend to focus on qualitative history because that is my strength, but I believe that Progress Studies cannot move forward as a serious discipline without fully embracing rigorous quantitative studies of past societies. We have a huge amount of quantitative data about current societies and those over the last 50 years or so.

However, there is a huge gap in pre-World War II databases. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, the further that we go back in time, the worse the problem gets. Most of my work relies on the Angus Maddison project, which is largely based on estimates of GDP and per capita GDP going back the last 2000 years.

But estimates can only take you so far. We need hard economic data from societies going back over the last 800 years, particularly those societies that historians believe were on the cutting edge of economic growth at the time. The Economies Past project is exactly what we need to test theories against real-world data.

One study using the Economies Past database comes to the following conclusions:

“All occupations have been classified into one of three sectors:

Primary sector: agriculture, forestry and fishing;

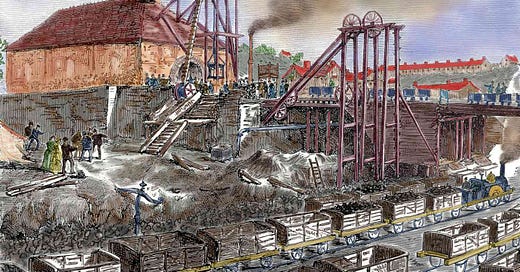

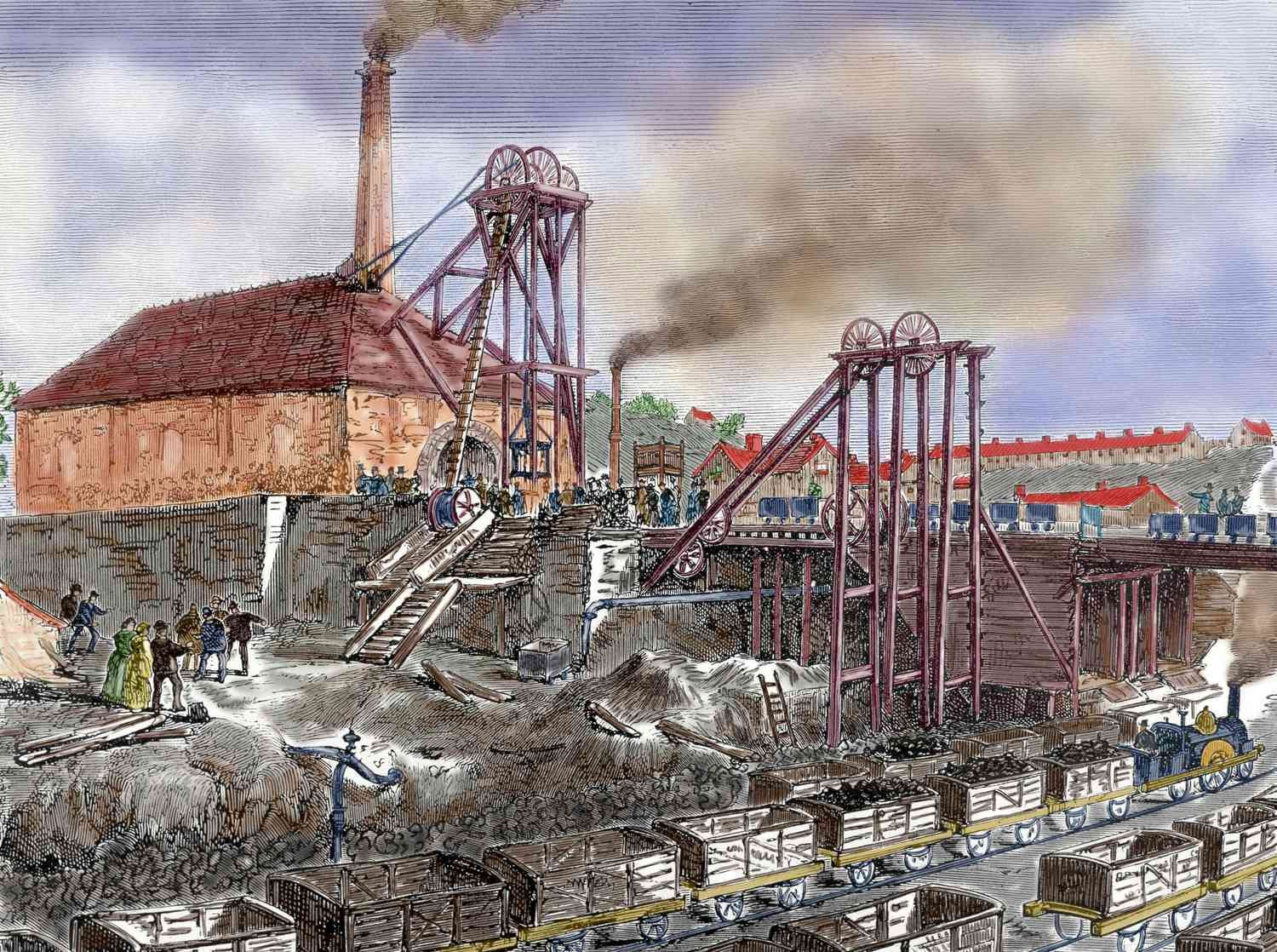

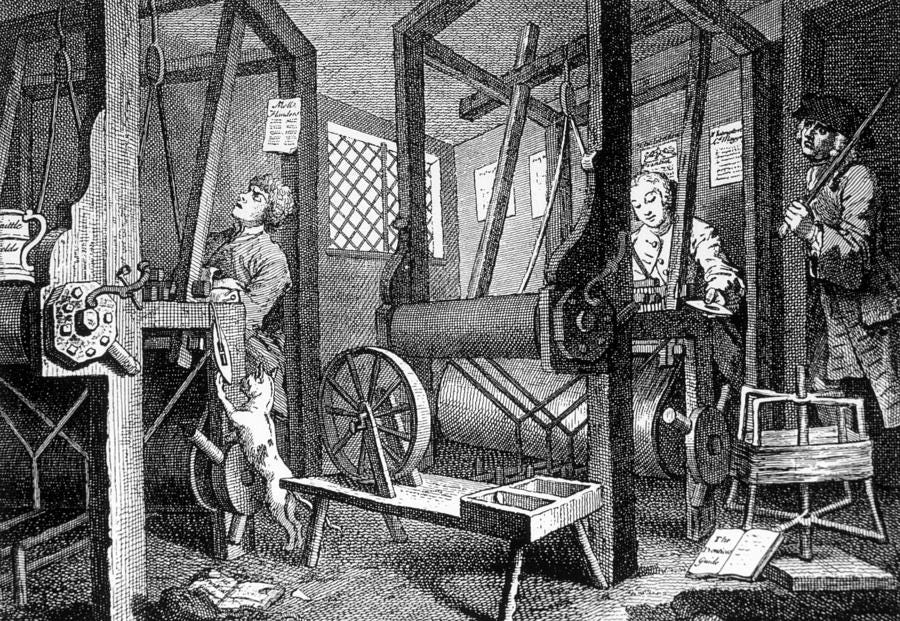

Secondary sector: mining, manufacturing, and construction;

Tertiary sector: anyone in services.

The most surprising, and most important, finding of the project is that the key period for the shift from the primary to the secondary sector was from 1600-1700, not 1750-1850 as 100 years of scholarship has assumed. In fact, the share of the male labour force in the secondary sector (excluding mining) was flat during the Industrial Revolution.

A second major finding is that the tertiary sector was the most dynamic sector of employment during the Industrial Revolution period.”

An overview of their findings is captured in this graphic:

One can see clearly that the Secondary sector (mining, manufacture, and construction):

Experienced a long, slow increase from less than 20% of all employment before 1400 to less than 30% in 1600

Then increased rapidly from 1600 to over 40% in 1700

Then hovered at 42-47% between 1700 and World War II.

During the same period, we also see a matching decrease in the percentage of all employment that was in the Agricultural sector. This seems counter-intuitive, as the first two periods are long before most historians believe the Industrial Revolution started, and the third period of supposedly radical economic change in the 19th century was a virtual flat-line in industrial employment.

How could the Industrial Revolution, one of the greatest economic transformations in world history, not lead to an increase in manufacturing employment?

What is also interesting is that the Tertiary sector, what we now call the service sector (a term that I will use going forward):

Experienced a long, slow increase from roughly 5% of all employment before 1400 to roughly 15% in 1800. This roughly matches the long, slow increase for the Secondary sector, but it was much longer in duration.

Then increased rapidly from 1800 to over 70% in the present day.

So it appears as if the Industrial Revolution:

Rapidly increased service-sector employment

But had little impact on manufacturing employment!

The authors of this study interpret this data as meaning that the Industrial Revolution started in the 17th Century, long before most economic historians believe.

See also my other articles on Commercial societies and related topics:

Commercial societies (where progress was invented)

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Some caveats

Implicit in this conclusion is that sectoral employment is a key metric for determining when the Industrial Revolution occurred. While I love the study, I have some serious reservations about the author’s interpretation of the data.

Employment is an input, but Progress Studies should be primarily focused on results (i.e. outputs). How many people working in a sector is far less important than what those people were able to produce.

There is also an important hidden assumption that there are two different types of societies:

Agricultural societies, which represent the old economic order, and

Industrial societies, which represented how a modern economy functions.

Using this model, researchers naturally look for data that shows increases in manufacturing employment and decreases in agricultural employment. Wherever we see sizable changes in the two, they assume that we then call this the Industrial Revolution.

An Alternative view of pre-Industrial Britain

The problem is that most economic historians fundamentally misunderstand pre-Industrial Britain. They often start with a caricature of pre-industrial Britain that, while partly true, differs greatly from reality. And period specialists tend to be so focused on Britain that they miss other societies that were quite similar. So for very different reasons, both schools tend to misunderstand how pre-industrial Britain compares with other societies at the same time.

In short, pre-industrial Britain was not just another agricultural society in Eurasia. Pre-industrial Britain was different from France, Germany, China, and India in many fundamental characteristics. And other societies in Europe at the time, for example the Dutch Republic, shared those same characteristics.

In short, pre-industrial Britain was a Commercial society. Remember that my definition of Commercial societies is that the majority of calories are procured from purchasing in the marketplace rather than producing food directly (as all previous societies did). According to the graphic above less than 50% of the labor market was employed in the Agriculture sector in the late 17th Century, so presumably they purchased their food rather than grew it themselves.

I believe that all Commercial societies see substantial:

Decreases in the proportion of workers in the Agricultural sector

Increases in the proportion of workers in manufacturing, construction, and service sectors.

My view is that there were three types of societies (not two):

Agrarian societies (such as France, Germany, and much of the rest of Eurasia)

Commercial societies which invented human material progress and was a necessary intermediate step before industrialization

Industrial societies, which added widespread use of fossil fuels. This radically accelerated progress and spread it to regions where it was impossible with pre-industrial technologies, skills, and organizations.

While the traditional interpretations stress what pre-industrial Britain had in common with France, Germany, and Italy, I stress the differences. And while the traditional interpretation tends to ignore Northern Italy, Flanders, and the Netherlands, I focus on those societies.

Most importantly, I see Commercial societies as a necessary precondition for the Industrial Revolution to have happened in the first place. Meanwhile, the traditional view is that Commercial societies did not exist, or at least were not that important.

My interpretation of the data

I am not at all surprised by the substantial increase in secondary employment in the 17th Century, because I believe that England was a Commercial society in that period. Increases in secondary and service-sector employment is an expected outcome of being a Commercial society. So the data is not evidence that Britain industrialized earlier than previous researchers thought. It is evidence that Britain was a Commercial society before it industrialized. I am confident that other European societies will show a similar trend.

My hope is that Progress Studies researchers expand the efforts to collect economic data on the Economies Past database into societies that I believe were also Commercial societies, such as:

Medieval city/states of Northern Italy (Venice, Florence, Genoa, Milan, and many more)

Late Medieval city/states of Flanders (Ghent, Bruges, Ypres, and Antwerp in modern-day Belgium)

The Dutch Republic (1579-1795)

Ideally, the database would also include other societies for control purposes, but these are the most critical to include.

My falsifiable predictions

My falsifiable prediction is that in every one of these Commercial societies, researchers will also find:

a rapid decrease in Agricultural employment as a percentage of the total labor force

a rapid increase in Secondary employment, particularly in manufacturing and construction.

an increase in Service sector employment.

There may be similar trends in other Agrarian societies in Eurasia, but they will be far less in scope. The vast majority of Eurasian societies will show little to no shifts in employment, but a distinct few will show substantial changes.

If I am correct, then these findings of as clear evidence there was an intermediate economic transformation before the Industrial Revolution that nicely fits into the category of Commercial societies first identified in the Scottish Enlightenment.

Adam Smith and some thinkers within the Scottish Enlightenment added a fourth type of society, Commercial societies, to explain the transition going on at that time. Adam Smith thought all societies would transition through all the other society types until they inevitably transitioned into modern Commercial societies. In fact, Adam Smith's classic work, The Wealth of Nations, came directly out of his desire to understand how Commercial societies function.

See also my other articles on Commercial societies and related topics:

Commercial societies (where progress was invented)

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Interesting essay on the possibility that the industrial revolution began in Britain a century or so earlier than originally thought.

I have to agree with you here, the change in employment noted during the 1600s does not mean that the industrial revolution started earlier, only that the pre-conditions for the industrial revolution were taking shape.

An industrial society is able to use heat energy, derived from fossil fuels, to do work as scale. The first workable steam engines were not invented until the early 1700s: https://www.lianeon.org/p/the-engines-of-progress

The question is, why was the steam engine invented in Britain and not elsewhere, like the Netherlands, which also had many of the pre-conditions of an industrial society?

I think the way to think about it is you need commerical societies for capitalism to take root. Song China and the Italian city states were pre-capitalist commercial societies. I note that China, despite having been a commercial society who used fossil fuels, never had an industrial revolution. The reason was they never development capitalism. Capitalism is tied into your third key to progress, decentralized elite power. The invention of capitalism created a whole new category of elites with different priorities than the old extractive elites, in that they *created* wealth from which they extracted a profit. The pie the old elite could draw on was fixed by the population size (agriculural output creates so many calories per person and so grows with population). The pie from which capitalists drew grew on a per capita basis, and so faster than the pie of the old elite. FOr example, during the Napoleonic Wars, Britain with 1/4 the population of France would as the war progressed have far more war potential (in that they could pay for large armies in Spain, Austria and Prussia) whom France had to fight using their own resources, which were inferior to those of the British.