How humans learned to transform food surplus into Progress

And they did so long before the Industrial Revolution

See also my other articles on Commercial societies and related topics:

Commercial societies (where progress was invented)

In a previous article, I explained the process by which humans combined energy with technologies, skills, and social organizations to create a food surplus and complex Agrarian societies. This process lasted roughly between the invention of agriculture about 10,000 years ago until well after the year 1200.

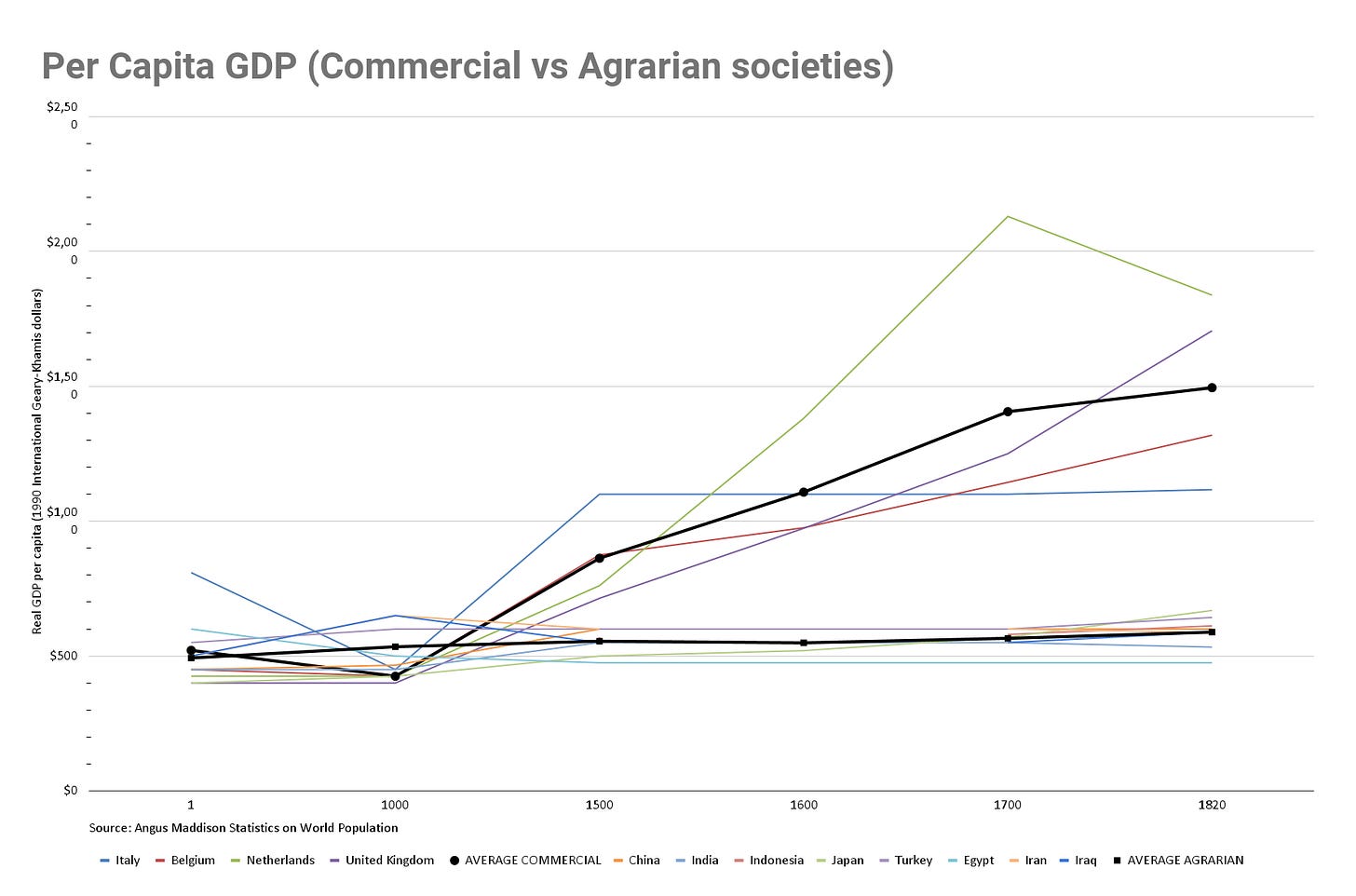

Agrarian societies were able to create a substantial food surplus, but they were not able to create material progress for the masses. The vast majority of the food surplus was extracted from the farmers by political, military, and religious elites for their own use.

I could recommend reading the following article before reading this article:

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Transforming the Food Surplus into Progress

Then around the year 1200, a few Commercial societies learned how to transform food surplus into a vast problem-solving network that generated real progress for the masses.

Commercial societies were to do this from a complicated set of interactions:

Step 1. In societies without centralized extractive institutions, the food surplus generated by increased agricultural productivity. This enabled farmers to trade with individuals who possessed skills related to non-agricultural technologies (for example bakers, blacksmiths, millers, and butchers).

Most of these cities remained very small local centers of trade. A few because of unique geographical circumstances grew to become major centers of trade.

Step 2. When trade reached a certain level, large trade-based cities with a wide variety of skills evolved.

Step 3. These trade-based cities created a virtuous cycle of technological innovation, skills acquisition, and social cooperation. This virtuous cycle included:

Increased population sizes, which led to more people who could potentially innovate.

Increased urbanization rates, which put those people in close contact with each other.

A greater number of market transactions.

Acquisition of new skills to conceive of, design, build, test, use, and repair new technologies.

Greater specialization of skills.

Greater cooperation between people within the same group.

Expansion of the sphere of cooperation beyond just the family to create larger and more specialized social organizations.

Higher levels of trust within the group.

Lower levels of violence within the group.

Increased positive-sum thinking (i.e. we can both get ahead by cooperating, rather than trying to sabotage each other by lying, stealing or killing)

Greater appreciation of achievement over status and military glory.

Greater willingness to copy other societies.

Step 4. This virtuous cycle within trade-based cities also has a powerful effect on institutions by:

Deepening the complexity of existing institutions as they put new technologies and skills to use.

Enabling the creation of new institutions based upon new technologies and skills.

Allowing existing institutions that are unable to make effective use of new technologies to collapse from lack of revenue.

Step 5. All of the above fed back into the technology base, enabling a faster rate of technological innovation. Each new piece of technology could then be used as a component in another more complex piece of technology.

Step 6. Finally, with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, the widespread usage of fossil fuels broadened the geographic scope of this process so that it encompassed more than just a few trade-based cities. The positive feedback loop could now affect entire regions, nations, and eventually continents.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my other articles on Commercial societies and related topics:

Commercial societies (where progress was invented)

Good summary.

I have a tendency to want to put the factors of Step 3 in a linear sequence of causation, with perhaps "8. Higher levels of trust within the group." being put in the 2nd or 3rd spot. But I suppose the reality was a mix of causation among these factors (something of a networked effect?), leading in turn to the ability to create trust between and among other groups outside of the local village or smallish city?

Is your argument that societies with rising agricultural productivity and an absence of centralized extractive authorities will experience a virtuous cycle toward being larger and more cooperative commercial societies?

In your opinion, is the Malthusian problem solved at that point? What if population grows faster than can be offset with productivity?

Also, what about external threats and decentralized exploitation and extraction from within?