Historians have misunderstood pre-Industrial England

It was unusual long before the Industrial Revolution

One of the main goals of my book series and this Substack column is to help build a solid intellectual foundation for the emerging field of Progress Studies. Progress studies is an interdisciplinary field of study that:

Promotes an awareness of progress:

Evidence that progress exists (my take on the subject)

Impact of progress on our daily lives (same link as above)

Promotes an understanding of progress:

Develops policies and practices that promote future progress:

Builds a coalition to implement those policies in the real world. This will mostly be within government, but the policies and practices are likely to have an important impact on private and non-profit organizations (my take).

To accomplish all those tasks, Progress Studies researchers must study history and look for policies and practices that can be useful today.

Pre-industrial Britain

One of the most important periods that Progress Studies researchers must study is pre-industrial Britain. In particular, Progress researchers need to understand how and why the Industrial Revolution happened in the following period.

Fortunately, an enormous amount of research has been done in this period. In fact, it is safe to say that it is one of the most carefully researched periods in all of human history. So rather than conducting original research, I think that it is more productive to place the knowledge that has already been acquired by previous researchers into a global context.

The historiography of pre-industrial Britain (roughly 1500-1800) has two main schools of thought. To simplify (and undoubtedly to over-simplify), I will divide them into:

Period specialists

Economic historians

Each of these schools has its strengths and weaknesses. Both add an enormous amount of value to Progress Studies, but both have missed a critical point.

Period Specialists

The first and largest school is the specialists in British or English history. Most focus exclusively on this period (roughly 1500-1800), as it is very complex and interesting, while others also focus on other periods of British history. What they both hold in common is that they focus exclusively on Britain (and particularly on London and southeast England). Most also specialize further in political history, social history, diplomatic history, military history, agricultural history, or on one specific region or person.

Period specialists do a great job of giving us rich historical details on the pre-industrial Britain. Many also present those details within a rich narrative. Unfortunately, period specialists rarely compare pre-industrial Britain to other societies. To the extent there is a comparison with other societies, it is typically with France or earlier periods in English history.

As a former History major in university, I love reading history books. I have great respect for the hard work done by historians in wading through massive and hard-to-read first-hand sources. Without them, the field of history and Progress Studies would be impossible.

The problem of N=1

Having said that, however, I believe that it is a mistake to focus too hard on just one society in just one period. It is so easy to get lost in all the details, and there is only so much you can understand about causality when your sample size is One.

For Progress Studies to flourish, we must adopt the comparative method by comparing and contrasting many nations and periods, and the larger the sample size the better. And should not just exclusively focus on societies. We also need to examine individual technologies and industries that span many societies and periods.

Progress Studies should be based on finding:

Commonalities among societies, industries, and technologies that experience progress

Where those same factors are lacking in other societies, industries, and technologies that do not experience progress

By examining many different societies, industries, and technologies, we can better sort our causality from the details. Ideally, this should be based on quantitative data, but often this is not possible, so it will need to be based on qualitative data.

This makes Progress Studies closer to Social Science than to History. Historians typically like to immerse themselves in one topic and are not necessarily interested in determining causality. Social Scientists, however, are primarily concerned with determining causality, so they find it necessary to span many different topics.

Economic Historians

The second school of historiography on pre-industrial Britain is composed of economic historians who are mainly trying to explain why Britain industrialized in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Their implicit comparison is between pre-industrial Britain and Industrial Britain of the 19th and early 20th century. Since the Industrial Revolution is one of the great economic transformations in world history, this is understandable.

Unfortunately, many economic historians start with an inaccurate view of pre-industrial Britain. Whenever one reads books about the Industrial Revolution in Britain, the author typically starts with an overview of pre-industrial British society. Invariably, the author notes that pre-industrial society was trapped in a Malthusian world where:

It was very difficult to increase agricultural productivity.

When it was achieved, the result was an increase in the number of babies.

Those babies gobbled up the food surplus leaving the general standard of living of the populace unchanged.

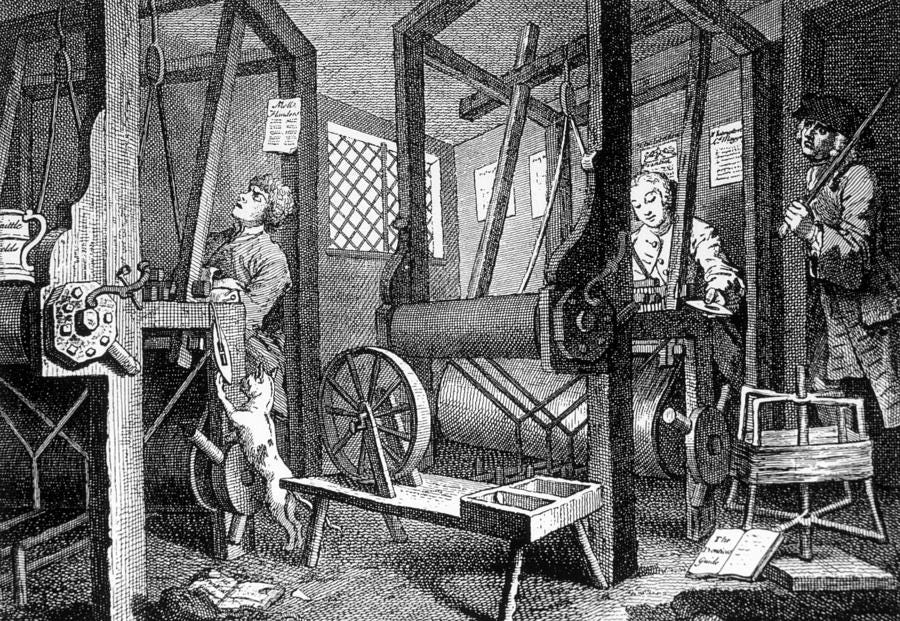

Many authors also point out that pre-industrial Britain was dominated by organic energy sources:

Human muscle power

Animal muscle power

Wind power (in mills and sailing ships)

Water power (in mills)

The authors then go on to show the enormous transformative effect of adding fossil fuels, in this case coal, as an energy source. The energy from that coal was then used to create innovations in a host of related technologies:

Transportation technologies, such as the railroad and the steamship

Communication technologies, such as the telegraph

Agricultural technologies, such as the tractor

Materials, such as iron and steel

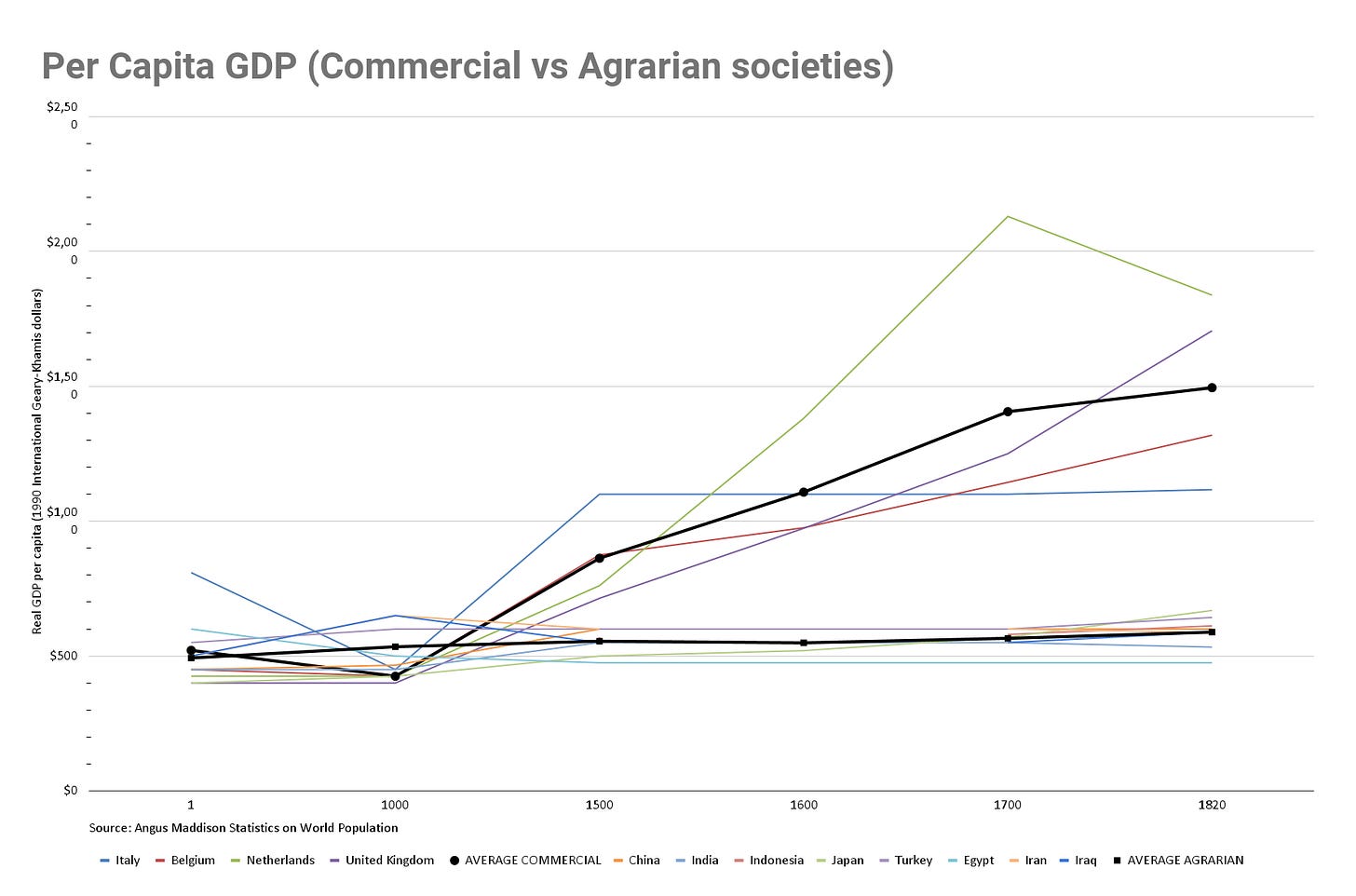

All of the above is true and important to understand, but I think that it misses some key points. Economic historians typically see two large categories of European societies:

Pre-industrial agricultural societies, which include pre-industrial Britain, France, Germany, and Italy (as well as much of Eurasia)

Industrial societies with the Industrial Revolution in Britain being the critical dividing line.

An Alternative view of pre-Industrial Britain

The problem is that most economic historians fundamentally misunderstand pre-Industrial Britain. They often start with a caricature of pre-industrial Britain that, while partly true, differs greatly from reality. And period specialists tend to be so focused on Britain that they miss other societies that were quite similar. So for very different reasons, both schools tend to misunderstand how pre-industrial Britain compares with other societies at the same time.

In short, pre-industrial Britain was not just another agricultural society in Eurasia. Pre-industrial Britain was different from France, Germany, China, and India in many fundamental characteristics. And other societies in Europe at the time shared those same characteristics.

In short, pre-industrial Britain was a Commercial society.

My view is that there were three types of societies (not two):

Agrarian societies (such as France, Germany and much of the rest of Eurasia)

Commercial societies which invented human material progress and was a necessary intermediate step before industrialization

Industrial societies, which radically accelerated progress and spread it to regions where it was impossible with pre-industrial technologies, skills, and organizations.

While the traditional interpretations stress what pre-industrial Britain had in common with France, Germany, and Italy, I stress the differences. And while the traditional interpretation tends to ignore Northern Italy, Flanders, and the Netherlands, I focus on those societies.

Most importantly, I see Commercial societies as a necessary precondition for the Industrial Revolution to have happened in the first place. Meanwhile, the traditional view is that Commercial societies did not exist, or at least were not that important.

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Pre-Industrial England

The most unusual Commercial society to emerge in the early modern era was England. While many historians believe that it was the Industrial Revolution that distinguished England from the rest of Europe, I believe that England and particularly Southeast England transformed into a Commercial society beforehand. Indeed, it was being a Commercial Society that enabled Britain to experience an Industrial Revolution in the first place.

By copying the innovations from other Commercial societies, particularly Flanders and the Dutch Republic, Southeastern England effectively became a Commercial society within a larger Agrarian England. Southeastern England possessed the innovativeness of Commercial societies but with a far larger population base.

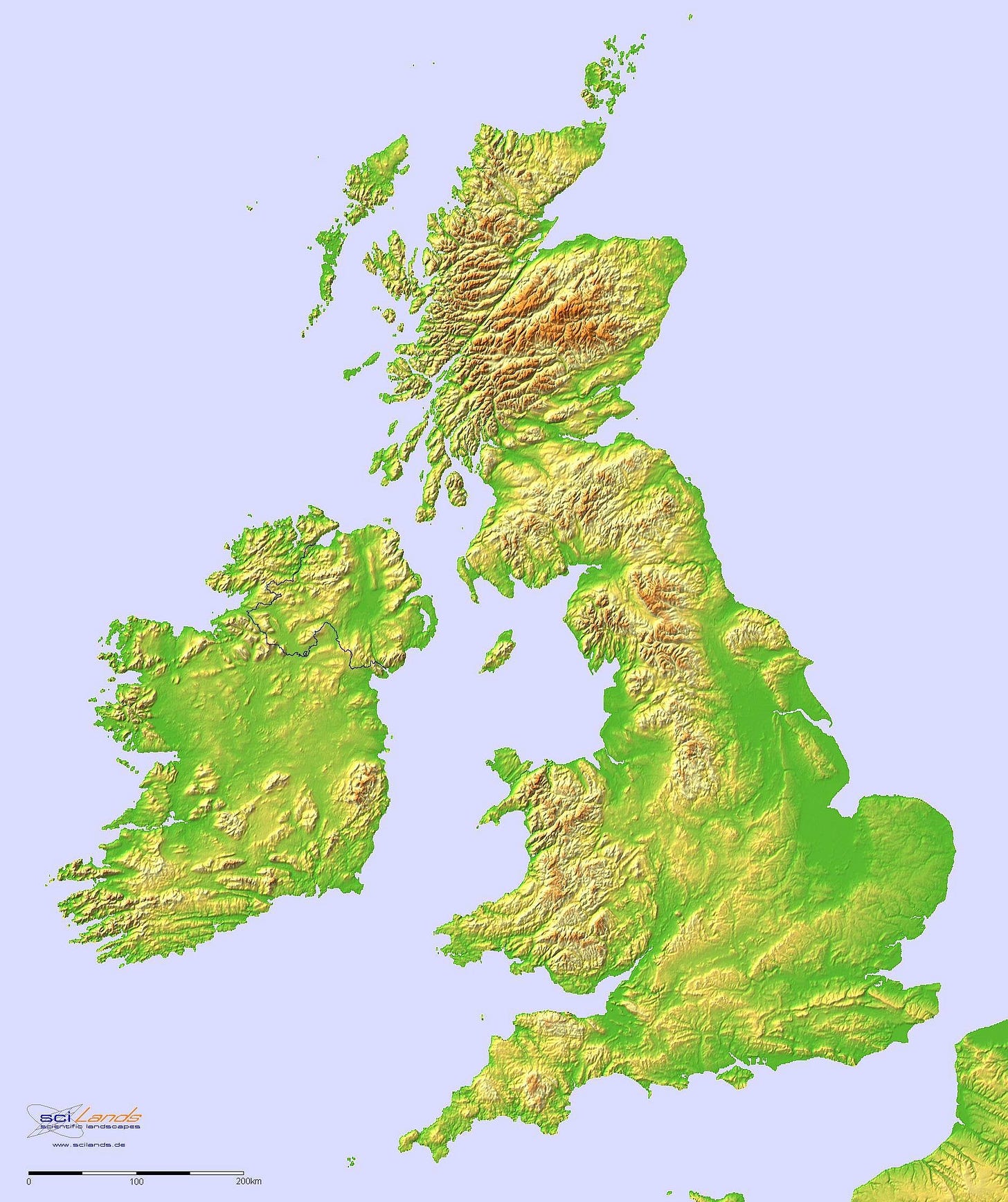

In some ways, England was a little different from the Agrarian societies in both Europe and Asia. England had:

a centralized monarchy,

titled elites with massive landholdings and

limited urbanization.

This made England very similar to Agrarian societies.

However, unlike most of the rest of the European continent, major portions of England gradually transitioned from being an Agrarian society to being a Commercial society. This transition enabled a level of economic growth that differentiated southeast England from most of the Continent long before the Industrial Revolution.

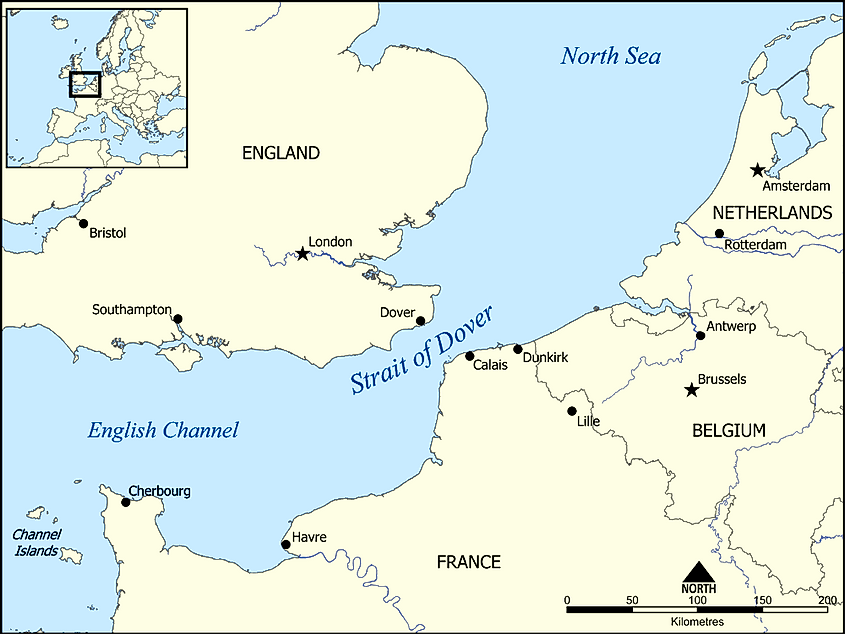

This transition occurred for a few key reasons. First, Britain had a huge geographical advantage: the English Channel. The “world’s largest moat” was a substantial geographical barrier to Medieval armies who lacked organized naval power. Of course, this made it difficult for England to project power onto the Continent as well. Unlike the Commercial societies of the Continent who were constantly fighting for survival against larger Agrarian states, England had far greater security.

While England shared the geographical advantages of Northwest Europe – Temperate Forest biome, productive soils, extended plains, and navigable rivers – the other societies on the British Isles were not as blessed. Wales, Scotland, and Ireland were largely highlands with less productive soil, and they were much further from the dynamic economies of Flanders and the Netherlands. Because of this, the other societies in the British Isles were far poorer and weaker. For these reasons, England rarely faced a serious military challenge within the British Isles.

This lack of a clear military threat meant that England never needed the huge standing armies that the Continental powers found necessary to survive. While kings on the Continent had to fight to survive, the English monarchs could largely choose their wars, and if they lost, the entire kingdom was generally not in danger.

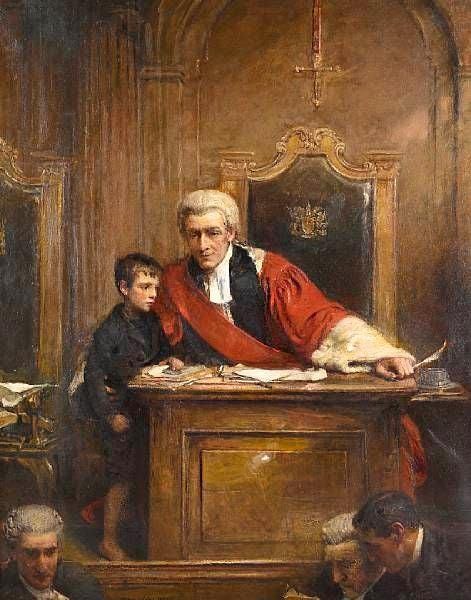

This meant that the gentry and the monarchy gradually worked out a balance of power that maintained a centralized government that protected society from hostile external powers while respecting the economic rights of citizens. This balance of power was institutionalized in the:

Magna Carta, which gave nobles rights that the King could not violate

English Common Law, which applied the rule of law to all monarchs, nobles, and later commoners.

Autonomy for cities, particularly London

House of Commons, whose approval the King needed to raise armies

While not as inclusive as governments in other Commercial societies, England’s political and economic institutions were far more inclusive than the Agrarian states on the Continent.

Proximity to the dynamic Commercial societies of Flanders and the Netherlands was central to the transformation of England from an Agrarian society to a Commercial society. There was a continual flow of people, technologies, skills, social organizations, and values from the Low Countries to Southeast England. While the transformation was much slower to diffuse to other parts of England, East Anglia, and London played a leading role.

The result was some of the strongest economic growth the world had seen before the Industrial Revolution.

In my book series and Substack column, I focus on the concept of the Five Keys to Progress. I believe that the Five Keys to Progress is an essential unifying concept for understanding human material progress. They are critical because they are the necessary preconditions for a society changing from a state of poverty to a state of progress, and they are actionable in today’s world. In other words, the concept not only helps to understand the world but also how to make it better.

The third Key to Progress is Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. It is of particular importance that elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses. This also allows citizens to freely choose among institutions based upon how much they have to offer to each individual and society in general.

Previous Commercial societies achieved this decentralization of power with:

separate city/states (as in Northern Italy and Flanders) or

a very decentralized political system that effectively gave cities a veto power of centralized government (as in the Dutch Republic).

These two methods of decentralization had many advantages, but they had one big disadvantage: in the zeros-sum military struggle between the Great Powers of the European continent, it was difficult to combine this type of decentralization with a powerful military capable of defending society. And the wealthier the society got, the more of a target they were for predatory empires.

This key weakness is exactly why the:

The city/states of Northern Italy were conquered by the French, Spanish, and Austrian empires after 1494. This led to a long-term collapse in their rates of economic growth.

The city/states of Flanders were conquered by the Spanish empire in the 1550s. This also led to a long-term collapse in their rates of economic growth.

The Dutch Republic was almost conquered by the French army in the 1670s, and it was afterward caught between the zero-sum mercantilistic economic and military policies of the British and French empires. The Dutch Republic finally succumbed to France in the 1790s and it was extinguished from history.

The problem is that the factors that encourage long-term economic growth that benefits the masses are the opposite is what builds a powerful military machine. To be successful in the long run, societies with progress need both.

But how?

The British solved the conundrum

Fortunately, for all of us, the British figured out a way to maintain political, civil, and economic rights within a much larger nation (and eventually a global empire) with a centralized government. They achieved this with:

checks and balances and

the rule of law within a centralized government that ensured that no man or group of men, even the King, could dominate others.

The British were able to achieve:

Long-term economic growth that benefits the masses

A powerful military machine capable of defending the nation (and spreading its ways to other regions).

It was a model that impressed the Founding Fathers of the United States, so they did the sensible thing and copied it.

Most of the above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

See also my other articles on Commercial societies and related topics:

Commercial societies (where progress was invented)

I remember reading a book that argued that agriculture in England was substantially more productive than in other places in Europe, leading to a large proportion of residents living in cities. (I think the author was named something like Ellen Meiksins Woods?) The argument was that England had a much more extensive market for agricultural land, leading to people who rented farm land to focus on raising yields and profits and for successful farmers to bid up the price of land. Was England unusually urbanized and did it have an unusual agricultural surplus?

Nice post. I'd add one other factor, literacy. The UK has a very long history of people being able to both read and write. This gave individuals without formal education the possibility to learn, about their business, about their rights, contracts. It helped level the playing field with the Church and State and the Landed Gentry. It also allowed much more complex economic interactions, with contracts for leasing of land, sub-letting, contract farming and harvesting etc. Literacy is absolutely essential.