How geography enabled Northwest European progress

Because the region has fewer constraints on food production

A major focus of my book series and this Substack column is the geographical foundations of modern progress. In particular, I am interested in geographical factors that enabled complex societies to evolve.

By complex societies, I mean:

Agrarian societies (who acquired their food calories from plow-based agriculture)

Commercial societies (who invented progress)

Industrial societies (which most of us live in today)

First of all, let me be clear.

Geography does not create human material progress. Geography is a constraint on human material progress, but some regions have fewer constraints than others.

In this article, I will focus on one region that had far fewer geographical constraints than virtually all other regions: Northwest Europe. These lower geographical constraints are a necessary, but not sufficient precondition to modern material progress.

The key variable is the extent to which the region enables the first of the Five Keys to Progress: a highly productive food production and distribution system. Without this first Key to Progress, no material progress (defined here) is possible until the Industrial era. And we could not have gotten to the first Key if there wasn’t a region with geographical factors like Northwest Europe.

The Industrial Revolution applied the awesome energy density of fossil fuels to innovate new agricultural, transportation, communication, and manufacturing technologies. This suite of revolutionary technologies enabled other nations to overcome geographical constraints to food production. For the first time, other regions could escape the trap of geography.

One of the most important questions in economic history is: Why did Northwest Europe get rich first? Some thinkers have credited culture or religion, other thinkers have credited politics; others have credited institutions; others credit specific historical events, such as the Protestant Reformation, the Glorious Revolution, or the discovery of the Americas.

While I believe that all those factors played some role, we must first start with geography. Geography is one thing (along with biology and energy) that we know for sure preceded humanity, so if it can account for variation, it is clearly a cause of progress not a result of progress. Without the geographical factors that enabled progress, none of the other factors would have mattered.

In this series how geography has influenced economic development by region, I define regions by natural geographic borders, not modern political borders. So I define Europe as Northwest and Central Europe.

By Northwest Europe, I mean the present-day UK, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, most of France, northwest Germany, lowland Switzerland, and the Po River valley in Northern Italy. I know the last one is cheating a little bit, but the Po river valley has many characteristics similar to the above nations.

By Central Europe, I mean all the present-day nations to the east of the nations listed above and to the west of Russia and Ukraine. I will periodically discuss those nations in this article, but it is not my main focus.

I discuss the Scandinavia peninsula in an upcoming article about Northern Eurasia, and the Mediterranean Europe in a previous article.

Much of this post is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Other articles about how geography has influenced economic development by region:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

How geography constrained progress (intro to this series)

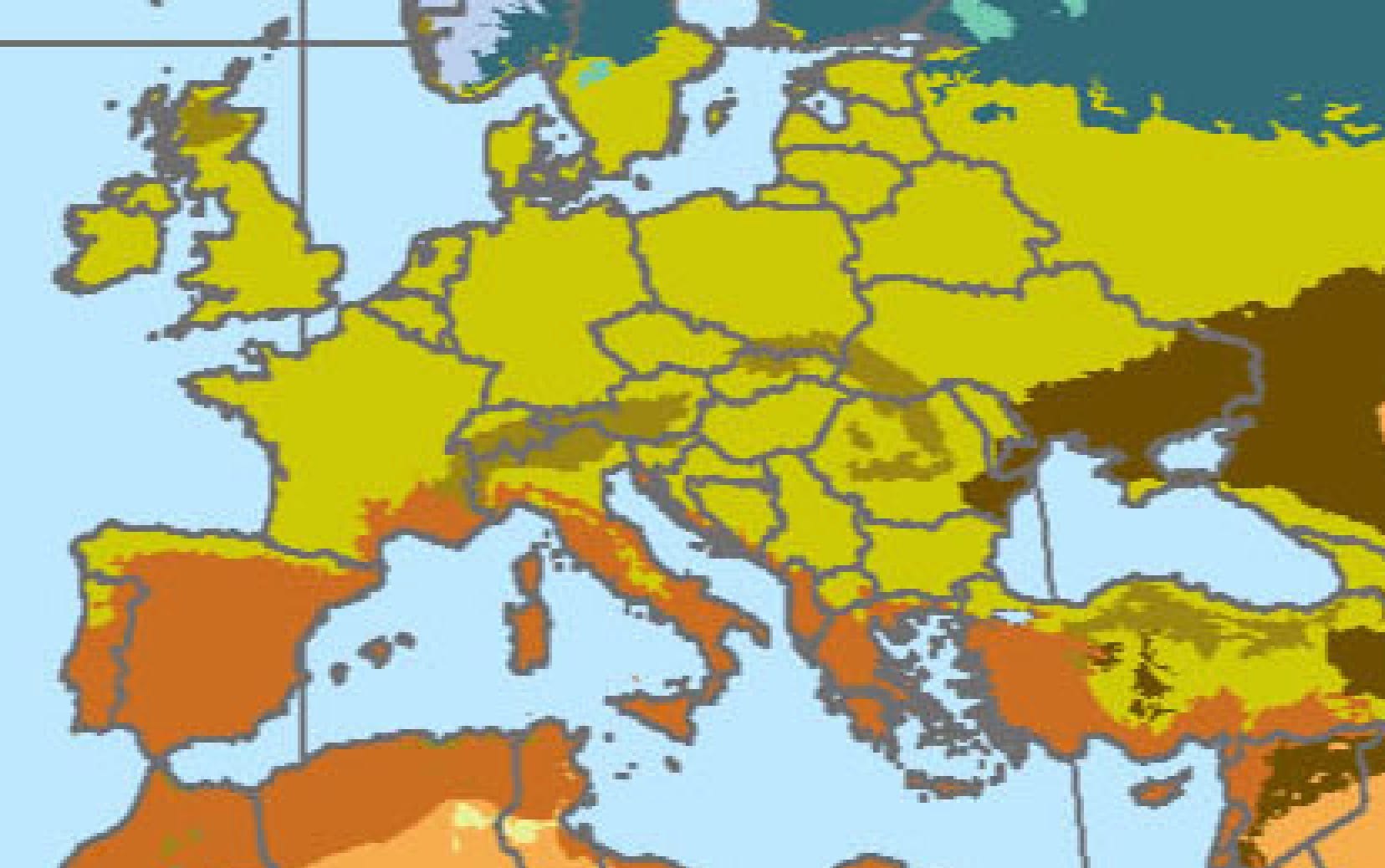

Biomes

The single most important factor in whether a region enables complex societies to evolve is its biome. A biome is a category for a geographical area based on its dominant vegetation. The dominant vegetation in any area sets very broad constraints on what type of plants and animals can evolve there. The dominant vegetation sustains the local herbivores, which then sustain the local carnivores. Since humans use a portion of these plants and animals as base materials for food production, biomes play a critical role in constraining the types of human societies that can develop within them.

Plow-based agriculture, a necessary transition step to modern progress, is only possible at a distance from river basins in a few biomes:

Temperate Forest biomes

Mediterranean biomes

(after the invention of the steel plow in the 1830s) Temperate Grassland biomes.

The European peninsula is dominated by the most massive expanse of Temperate Forest biome in the world. Only North America and China are anywhere near it in size. If you want one simple reason why Europe got rich first, this is it. This one simple fact virtually ensured that agricultural societies would evolve in the region.

I also want to point out that Northwest Europe had a very specific type of Temperate Forest biome called a “Deciduous Forest.” Most of the rest of Europe had “Mixed Deciduous/Coniferous Forests.”

Deciduous trees are much more conducive to agriculture than conifers. While needles on conifers and leaves in tropical latitudes stay on the tree year-round, most deciduous trees in temperate latitudes go through a seasonal cycle of losing their leaves in the autumn and then regrowing them in the spring.

When nitrogen-rich leaves fall to the ground in the autumn and then unfreeze in late winter and early spring, they create a thick layer of humus on top of the soil. Spring rains wash the nutrients deeper into the soil, where huge numbers of decomposing bacteria and animals ensure these nutrients nourish the deepest layers of soil. Those nutrients from the leaves are then gathered by plant roots from the soil and redirected into growing new leaves. This constant seasonal cycle ensures that Temperate Forests have some of the most productive soils in the world.

The biggest disadvantage of conifer trees for other species, including humans, is that needles decay very slowly. The combination of thick waxy needles and a very limited amount of decomposing bacteria and animals in the region means that a thick layer of dried needles usually covers the topsoil. This interferes with seedlings’ growth, creating “dead zones” with at most a few saplings or shrubs immediately below each large tree. These mats cause the soil to become highly acidic and unproductive for plants or agriculture.

So if you want to know why Northwest Europe got rich long before Central and Eastern Europe, the type of forests is likely the most important reason. More on this in a future article.

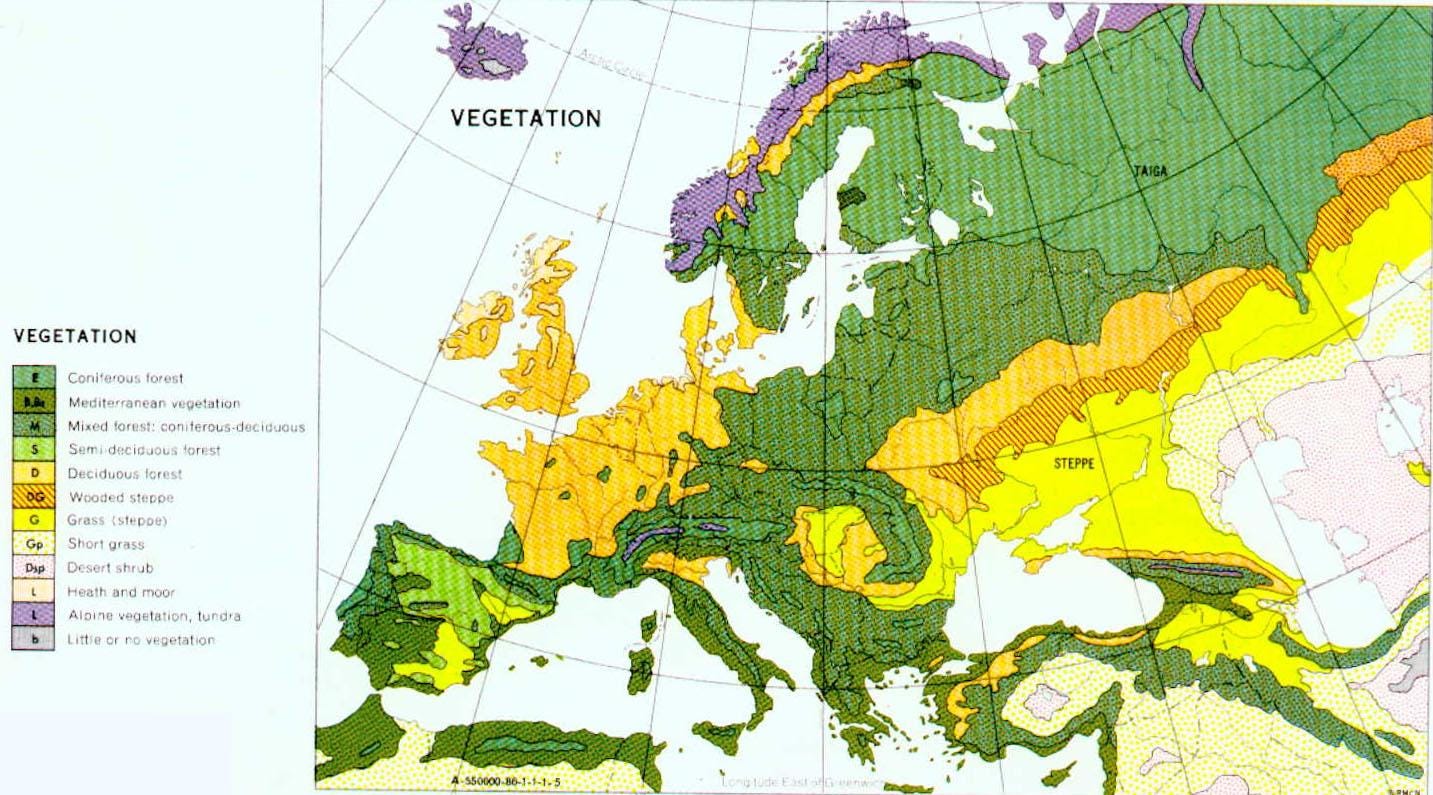

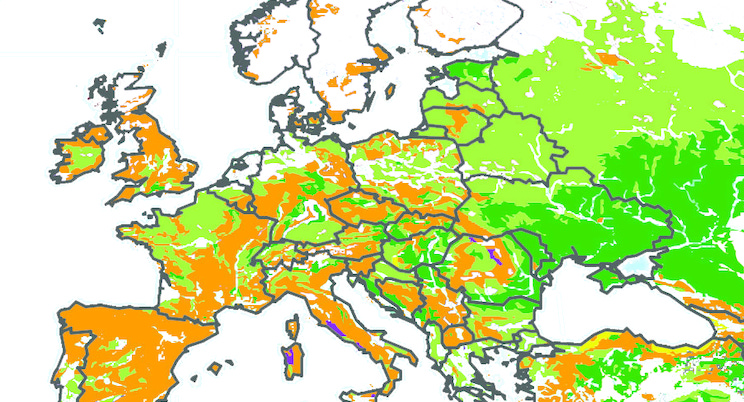

Soil

Even with the proper biomes, a region needs fertile soil for agriculture. Because agriculture is key to feeding dense human populations, the type of soil in a region is critical to its ability to support complex societies. Soil is the combination of:

weathered rock,

air,

water, and

organic matter from decomposing plants and animals.

A quick glance at the maps above shows how blessed Europe is with fertile soil for agriculture. Alfisols (light green) and Inceptisols (orange) cover most of the region. Mollisols dominate Ukraine and southern Russia. In general, Alfisols tend to be more productive than Inceptisols, but they both enable some form of productive agriculture (if combined with other factors). Mollisols were only possible to plant at scale with the invention of the steel plow in 1830 (which I will discuss in another article)

Note also the heavy concentration of Alfisols around Paris, northern France, and Belgium. This helps to explain why this region was the core of France, the dominant Agrarian power on the Continent for centuries. In the pre-industrial era, productive soil leads to larger populations, which then lead to more dominant armies and royal bureaucracies. More on this in a future article.

Rivers

Most large and prosperous cities are located on rivers or natural ocean ports. Rivers offer crucial advantages to human development. Rivers:

Offer sources of (hopefully) clean drinking water.

Make it easier to remove human waste.

Offer sources of irrigation for crops.

Deposit additional nutrients in the soil for growing crops.

Enable cost-effective transportation of people and freight.

Offer defensible lines to block the approach of enemy armies.

Northern Europe is also blessed with a vast network of navigable rivers. Virtually every major European city was on the banks of such rivers. And they were typically located on particularly strategic sections of those rivers.

So geography of Europe made the location of major cities somewhat inevitable. Any city that was not blessed by riverine geography would be out-competed by other cities that were.

Because these waters flowed through biomes and soil types that enabled highly productive agriculture, these rivers were particularly useful for humanity. I will write future articles on the most important rivers in Europe, but they are:

The Greater Rhine river system, which contains many important tributaries, such as the Meuse/Mass, Ruhr, Main, and Neckar rivers. This was the heartland of Dutch, German, and Swiss political and commercial activity.

The Greater Po river system, which formed the heart of Northern Italian political and commercial activity (Venice, Milan, and a gaggle of other lesser cities).

The Thames river, which formed the heart of English political and commercial activity (i.e. London).

The Seine river, which formed the heart of French political and commercial activity (i.e. Paris).

The Scheldt river, which formed the heart of Flemish and later Belgian political and commercial activity (i.e. Antwerp and lesser cities such as Cambrai, Ghent, and Lueven).

It is not a coincidence that all these rivers, except the Po, have mouths within 250 miles of each other. This closely connected network of navigable rivers flowing through fertile land virtually guaranteed that Northwest Europe would become a dynamic Agrarian center of politics, military, trade, and industry.

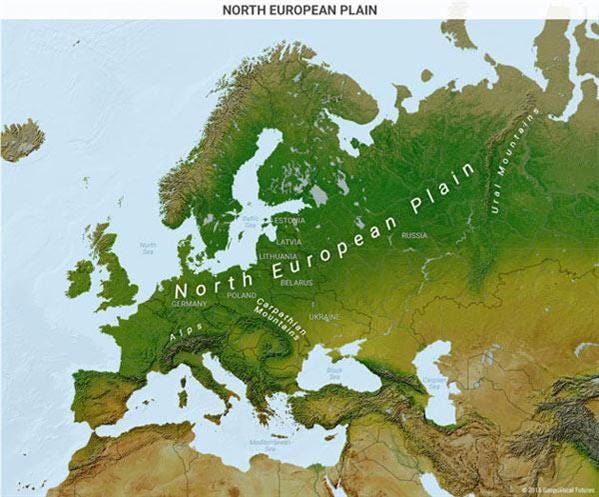

Altitude

Except for Highlands in Tropical latitudes, complex societies are concentrated on the plains at altitudes of 500 meters or lower. While landmass on Earth varies in altitude from just below sea level to 10,000 meters above, about 73.7 percent of humanity inhabits altitudes of less than 500 meters above sea level.

Here again, Northwest Europe is blessed by geography. The Northern European Plain is one of the largest plains in the world. This plain stretches from the French Atlantic coastline through modern-day Germany and Central Europe all the way to Russia. Not surprisingly, this plain is the site of the vast majority of the greatest military battles that shaped human history.

It should also not be a surprise that the mountainous regions within the European continent have always been far more backward economically today and throughout history. Their only advantage was that no one wanted to conquer those regions because they were easy to defend, had infertile soil, and typically offered few resources.

By itself, the Northern European Plain is not terribly important, but in combination with the other factors listed in this article, this enormous plain was a huge geographical advantage for Europe.

Decentralization of Power

Notice also, that this enormous plain broken up into many separate river valleys would have been very difficult for any one power to conquer (although many powers tried). I do not believe that this characteristic guaranteed the decentralization of political, economic, religious, and military power, but it made it far more likely.

So rather than one big European empire, the region evolved into many competing Agrarian powers competing with each other militarily, politically, and economically. This was decentralization of power at a very high level. And the fact that they all shared the same religion and language group probably enabled copying of what works. Whoever failed to copy what works was doomed to extinction.

This decentralization is the third Key to Progress: Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. It is of particular importance that elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses. This also allows citizens to freely choose among institutions based on how much they have to offer to each individual and society in general.

Growing Season

Even if a region has a desirable biome, low altitude, and agriculturally productive soil types, other factors can preclude the development of productive agriculture. Even in areas that have all the necessary factors, some days are too hot; some days are too cold; some days have too much rain and other days have too little rain. One or two days of any of the above are not a problem, but if those days are strung together for weeks or months, agricultural production is seriously constrained.

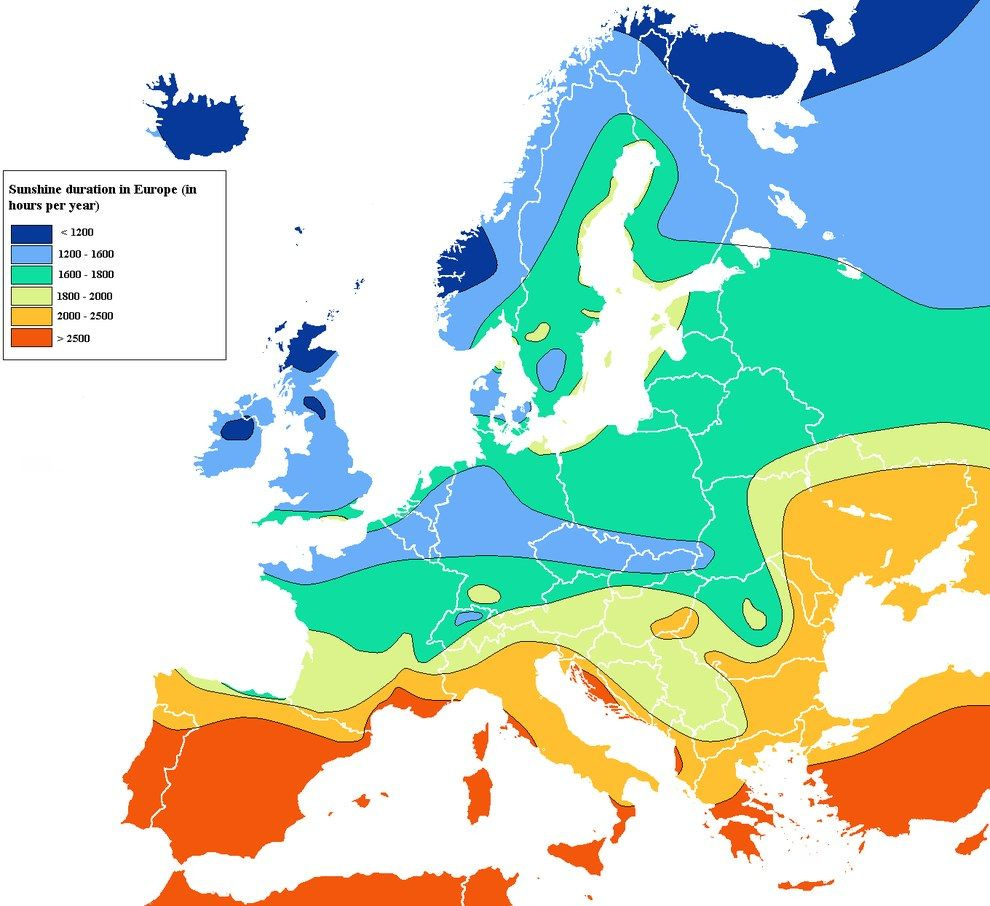

While I could not find good data on the length of Growing Seasons outside Eurasia and North Africa, it is clear that this is another domain where Europe was blessed by geography. Virtually the entire continent has a Growing Season of over 210 days per year. With the exception of East Asia and other scattered regions, Europe had unusually long Growing Seasons. This should not be surprising given its moderate temperatures and precipitation pattern.

I find it interesting that most of England is an exception. Given the huge role that England played in modern material progress long before the Industrial Revolution, I must admit that I cannot explain this discrepancy.

Obviously, this must be due to excess rainfall and clouds, which every Englishman can attest to. It is, however, not clear that England is that different from the rest of Northwest Europe in this characteristic.

I can find no evidence that a shorter Growing Season seriously undermined English agricultural productivity, so I am not quite sure what is going on here. But even England has a longer Growing Season than most of Eurasia.

Wild ancestors of domesticated animals and plants

Most of the factors that enable productive agriculture are pure geography, but biogeography also plays an important role. Productive agriculture requires domesticated animals and domesticated plants. In particular, a region needs:

Animals that provide a reliable source of protein and fatty acids: cows, pigs, goats, sheep, or chickens.

Animals that are capable of pulling plows: horses, cows, or water buffalo

Staple crops that provide dense sources of carbohydrates, such as rice, wheat, corn, or potatoes.

Before a society can domesticate a plant or animal, the wild ancestors of those plants and animals need to be either:

located in the region or

close enough that human migration can bring those domesticated animals into the region.

Now, we are finally coming to a geographic factor where Europe did not stand out in a favorable way. To the best of my knowledge, not a single important domesticated crop or animal originated in Northwest Europe. Because geography is about constraints, this one constraint might have made the evolution of Agrarian societies impossible.

As I explained in my article on North American geography, this one seemingly insignificant geographical constraint might have made it impossible for Northwest Europe to evolve beyond Horticultural societies. Horticultural societies have agriculture, but they lack animal-traction plows, so the productivity of their agriculture is generally significantly less than that of Agrarian societies.

Without a factor that I will identify later in this article, Europe might have more resembled pre-Columbian Horticultural societies in North America, modern-day Mexico (Aztecs), the Andes (Incas), and New Guinea. European material progress would have been impossible, and world history would have been dramatically different from the current timeline.

The Industrial Revolution would likely have never happened, because the evolution of Commercial societies was a critical pre-condition to the Industrial Revolution. I argue that the Commercial societies of Northwest Europe (Northern Italy, Flanders, the Netherlands, and southeast England) were not inevitable because they required unique political and geographic conditions that only existed in Northwest Europe.

The critical sequence is:

Commercial society, which invented material progress >

Industrial Revolution, which expanded existing material progress.

Geography plays a massive constraint on each of these stages, so most regions have a hard cap on the level of complexity of human societies that can evolve without assistance from outside.

The Industrial Revolution and the global free trade order established after World War II made this assistance possible.

The threat of Herding societies

As Peter Turchin has argued (summary here on my online library of book summaries), until the widespread use of firearms and cannons, the horse archers of the Eurasian steppe were the dominant military threat to Agrarian societies.

Agrarian societies that were located near Temperate Grassland biomes in Eurasia with horse archers faced an existential threat. Combining rapid strategic and tactical mobility with standoff weapons in the form of the composite bow-and-arrow, the Herding societies of the steppe were dangerous enemies.

In the period between 400 and 1500, these peoples formed expansive empires that dominated the Agrarian societies of China, Korea, India, Persia, Russia, and the Middle East. While these empires were often short-lived and led to few long-term changes, they did have a devastating impact on the lands that they conquered.

Despite their ability to dominate Agrarian societies, it is doubtful whether Herding societies were able to deliver progress to their people in the long term. Undoubtedly, the conquest of richer Agrarian societies enabled them to extract greater resources from farmers, but most of these empires were fleeting in duration.

More importantly, these Herding empires were parasitic in nature. Rather than creating wealth, they extracted wealth from Agrarian societies through military conquest. Once Herding societies lost their military dominance because of the invention of firearms, their people returned to their poorer Herding lifestyle.

Here is just a partial list of the most significant steppe nomad grups who conquered huge swathes of adjoining regions. You can click the links to learn more about each:

Mongol Empire, the largest and most famous.

Scythians, who dominated the Pontic steppe from the 3rd Century BCE to 600 BC

Sarmatians, who dominated the Pontic steppe in the 3rd-4th Century BCE

Xiongnu, the first of the eastern steppe herders who influenced China

Kushan Empire, which dominated Central Asia and northern India around the 2nd Century

Huns, who played a key role in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The Germanic tribe who actually conquered the Romans were basically trying to flee from the Huns.

Mughal Empire, who dominated India for 350 years before the arrival of the British.

Seljuk Empire, who dominated the Middle East from 1037-1194.

Various Turkic tribes, who conquered the Byzantine empire and conquered most of the Middle East, Balkans, and North Africa. They founded the Ottoman Empire, one of the greatest empires of the Agrarian era.

Bulgar Turks, who conquered and settled what is now Bulgaria between the 5th and 7th centuries.

Magyars, who conquered and settled what is now Hungary between the 5th and 7th centuries.

Arabs, (mounted warriors from the Arabian deserts) who conquered huge swathes of the Middle East, Persia, and North Africa.

A large number of Central Asian tribes, who conquered and ruled China for a significant portion of Chinese history. Many “Chinese dynasties” were actually dominated by non-Chinese conquerors from the North. Throughout Chinese history, the threat from the Central Asian tribes was the primary military threat.

In contrast to most of the rest of Eurasia, Northwest Europe had moderate levels of military threats from the Herding societies of the Eurasia steppe. Notice that the above empires had little to no effect on Northwest Europe. Other than the Mongols and the Huns, the Vikings (a very different type of marauder) were the biggest security threat to Northwest Europe.

China, Central Asia, India, Russia, and the Middle East were frequently conquered by aggressive and destructive steppe warriors. These wars of conquests left devastation that took decades or sometimes even centuries to recover from. But not for Northwest Europe.

Eastern Europe and Central Europe created a buffer zone between the deserts and grasslands of Central Asia and the Deciduous forests of Northwest Europe. Horse-riding steppe herders had a hard time finding enough feed for their horses once they left their native grasslands. They could conquer and exploit surrounding regions, but they could only go so far away from their home region.

Fortunately for Northwest Europe, the region was just far enough away to minimize the long-term damage. The military threat of steppe horse archers was more episodic than a pandemic.

Military Competition

Of course, Europe was hardly a haven of peace. Indeed, it was the one corner of the earth most dominated by war, but it was war between Agrarian kingdoms with heavy infantry, not an asymmetric conflict between heavy infantry and horse archers.

This symmetric military conflict within Europe propelled political, military, and economic conflict without the devastation of horse archer raids. The strategic and tactical mobility of light cavalry combined with the projectile weapons of composite bows gave horse archers a huge military advantage in certain geographies but not in others.

Fortunately for Northwest Europe, the horse archers could not remain on their territory for very long before they had to retreat to the grasslands to feed their horses.

Geographical Isolation

Societies often develop by copying technologies, skills, and social organizations from other societies. And military conquest by other societies can seriously set back long-term development. Because of those two facts, neighboring societies have a major impact on societal development.

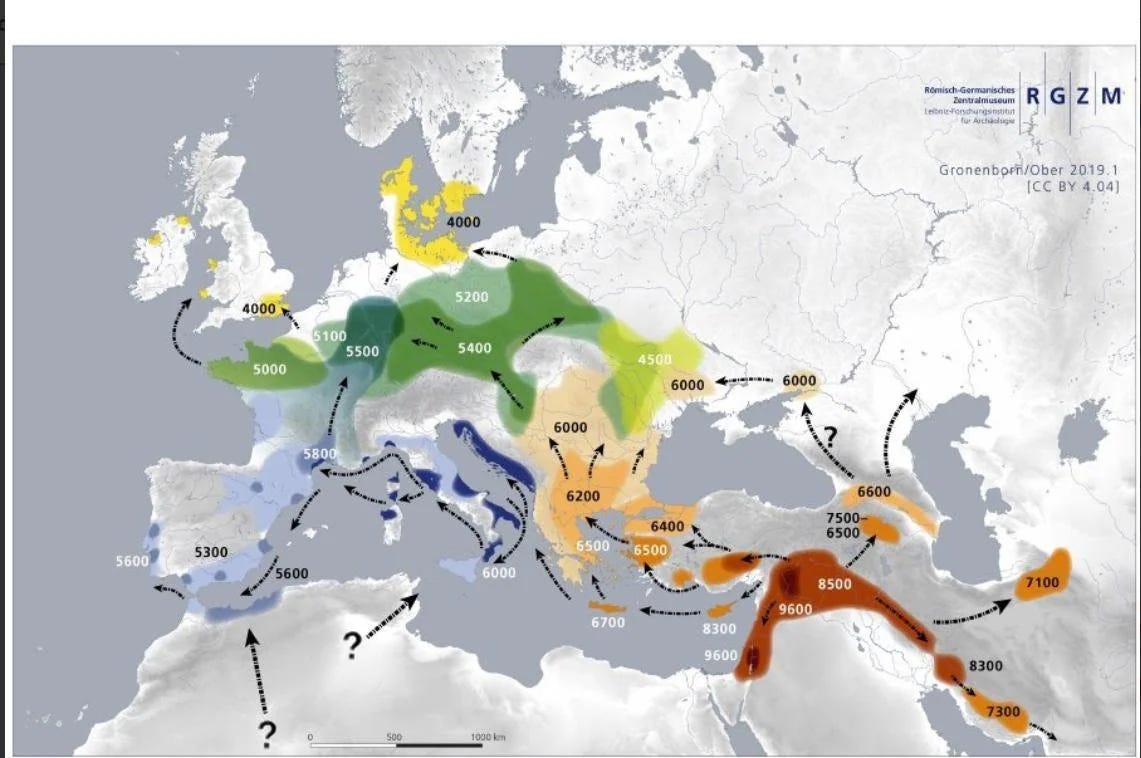

The most important such constraint was proximity to the Middle East. As we have seen, agriculture evolved in the Fertile Crescent (modern-day Syria, Iraq, and Southern Turkey). Early Agrarian societies in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia played an important role early in the Agrarian era. These regions played a critical role because they had many wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals.

As we have seen, Northwest Europe and most of the rest of Europe had all the critical geographic factors that enabled Agrarian agriculture and material progress, except one: a lack of wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals. Fortunately, the migrations of Anatolians from modern-day Turkey to the rest of Europe came with those missing ingredients. This meant that they brought all the key ingredients for Agrarian societies.

Without that Anatolian migration thousands of years ago, Europe would have likely remained Horticultural societies, such as pre-Columbian Horticultural societies in North America, modern-day Mexico (Aztecs), the Andes (Incas), and New Guinea. European material progress would have been impossible, and world history would have been dramatically different from the current timeline.

And it is even possible that Europe would never have evolved into Horticultural societies. It is not clear that European geography had the necessary wild ancestors of grains that made any agricultural societies possible.

Grains were a fundamental precondition of Horticultural societies. Only potatoes in the Andes made a suitable calorie substitute. Without grains from the Middle East, it is not clear whether any form of agricultural societies would have been possible. The historical ramifications of this are breathtaking. History as we know it would have been radically different with Europe’s proximity to the Middle East.

Conclusion

All of the above geographical factors combined made it virtually inevitable that Northwest Europe and, to a lesser extent, other sub-regions within Europe would evolve into dynamic Agrarian societies. East Asia is probably the only region that has similar geographical characteristics, although parts of South Asia and Southeast Asia might also be exceptions.

Now I want to make very clear what my argument is. I am not claiming that European geography:

Made it inevitable that Europe would get rich first.

Made it inevitable that the Industrial Revolution would take place in Northwest Europe.

Made it inevitable that the Industrial Revolution would take place at all.

Made it inevitable that the Commercial societies would evolve in the region.

Instead, I am arguing that all these geographical factors made all these critical historical transitions possible in Northwest Europe, but impossible in almost all other regions.

A shared history

Up until the year 1200, European history is strikingly similar to the histories of Agrarian societies in:

Middle East (Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia)

East Asia (China, Korea, Japan)

South Asia (the Indus river valley and the Indian sub-continent)

The river deltas of Southeast Asia

Despite their important cultural differences, they shared far more in common with each other in the domains of rates of innovation, religion, values, social immobility, demography, social stratification, obsession with status, writing systems, institutions, technology, politics, economics, military, urban characteristics, and agriculture. That is why it is so useful to see them all as different flavors of Agrarian societies.

If you are skeptical on this point, read my summary of “Why the West Rules-for Now: The Patterns of History” by Ian Morris in my library of online book summaries.

Up until the year 1200, the history of these five regions is also strikingly different from all the rest of the world. That is why the concept of society types and the geographical constraints that enable or preclude the evolution of new society types is so critical to understand. Agrarian regions could evolve in these five regions, but not in the other regions of the world. Many could not even invent agriculture of any type.

When Northwest Europe went its own way

It was only after 1200 that Northwest European history began to veer in a very different direction from the other four Agrarian regions. Geography played a role in that transition, but politics, institutions, and technological innovations played a more important role. Northwest Europe was able to do so because of the unique characteristics of Commercial societies, a type of society that only existed in a few parts of Northwest Europe.

These Commercial societies invented material progress and made the Industrial Revolution possible. The Industrial Revolution and the global free trade order established by the USA after World War II made it possible for other nations who had been trapped in poverty by geographical constraints to finally industrialize themselves.

So these small Commercial societies helped to transform the world.

Much of this post is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Other articles about how geography has influenced economic development by region:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

How geography constrained progress (intro to this series)

Some other great Substack columns on geography that you should subscribe to:

This is truly an amazing analysis. I've seen all of this elsewhere and in my econ training, but assembled together like this, it's a truly devastating argument.

"I can find no evidence that a shorter Growing Season seriously undermined English agricultural productivity"

Consider what David Ricardo chose to illustrate his theory -- Portugese wine and English wool -- clearly aware of the constraints of English agriculture. For Ricardo, latitude and precipitation IS comparative advantage. In the progress equation, the multiplier of the "ag-efficiency" variable may be quite high, but there are many other variables, as you say. Clearly, the Anglo-Norman people found a way (Ricardo implies using grazing instead of row crops) to overcome their weakness in this area and make the jump to a commercial society: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/daily-per-capita-caloric-supply?country=GBR~FRA As weird as it sounds, their comparative weakness may have encouraged that jump. I wonder what the meat/grain caloric ratio of Medieval France vs England was?

"For the first time, other regions could escape the trap of geography."

It is ironic that literally while Ricardo was creating his theories predicated on latitude and precipitation, other events were rendering those variables far less significant to comparative advantage and progress.

I enjoy all these write-ups. Speaking of geography, NW Europe really stands out when you look at a population density map of the world and notice that it's by far the northernmost part of the world that is densely inhabited. Cities like London and Paris share latitudes with parts of Manchuria and Siberia that are barely inhabited. Which tells you that there must be something very peculiar about NW Europe's geography. I understand this to be, primarily, the Gulf Stream, which I didn't see you call out directly, but presumably it's what accounts for NW Europe's unusually long growing season.

https://www.luminocity3d.org/WorldPopDen/#3/20.00/10.00

Let me also comment on this:

>I can find no evidence that a shorter Growing Season seriously undermined English agricultural productivity, so I am not quite sure what is going on here.

While I'll admit that I don't have detailed knowledge of the differences between medieval French and English agricultural production, didn't medieval France have something like 5x the population of medieval England on less than 2x the land area? I've always assumed this was mainly a result of French land being much more productive under the state of agricultural technology in that era.