How American farmers mechanized agriculture in the 19th Century

and drastically increased the food surplus

One of the key questions of history is why Europe got rich much earlier than other regions. A key part of the answer was its agriculture. Northwest Europe and the regions settled by people from that region experienced multiple agricultural revolutions. This is in startling contrast to virtually every other region in the world.

In every other agricultural region on the planet, the basic subsistence patterns for each agricultural region had evolved by about 500 BCE. While there was a great deal of geographical variation, subsistence patterns in all other regions evolved very little between 500 BCE and when they were first exposed to European conquest after 1500. That is stagnation for 2-8,000 years!

Even after European conquest, there was typically very little change in subsistence patterns outside Northwest Europe and North America until the late 20th Century. And outside of agricultural regions, change was even slower. Many societies were effectively trapped in subsistence patterns defined by their society type, and there was no possibility of change.

By the year 1800, Northwest Europe had undergone four distinct agricultural revolutions (each of which I discuss in the linked articles):

The Neolithic “slash-and-burn” farming system, which was imported by Horticultural migrants from the Middle East.

The Ancient farming system, which was the system used during the times of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and the Dark Ages.

The Medieval farming system was the first system that was unique to Northwest Europe. It was invented sometime between 700 and 900 and lasted until the 19th Century. This system roughly doubled farming productivity compared to the previous Ancient farming system.

The Commercial farming system, which eliminated fallowing, and roughly doubled farming productivity again. This farming system was largely restricted to Flanders, Netherlands, England, and regions settled by the English. This farming system was so productive that it made up a foundation of modern progress.

The progressive transformation of farming systems enabled:

Large increases in population

Increased urbanization

A significant improvement in diet

Larger and more effective militaries

But this was just the beginning. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, the leading edge of agricultural innovation shifted to the United States. American industry invented a large number of horse-drawn farming devices that radically increased farming productivity. These innovations later spread to Canada, Australia, and Argentina. Only after a significant time delay did they diffuse back to Europe.

Note: the following description and graphics were adapted from A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart. You can find a more detailed summary in my online library of book summaries.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

Horse power

The key trend in this 19th Century agricultural transformation was mechanization. We tend to think of mechanization as the application of:

steam engines

electricity, or

internal combustion engines.

The first wave of agricultural mechanization was based on horse-drawn farming implements.

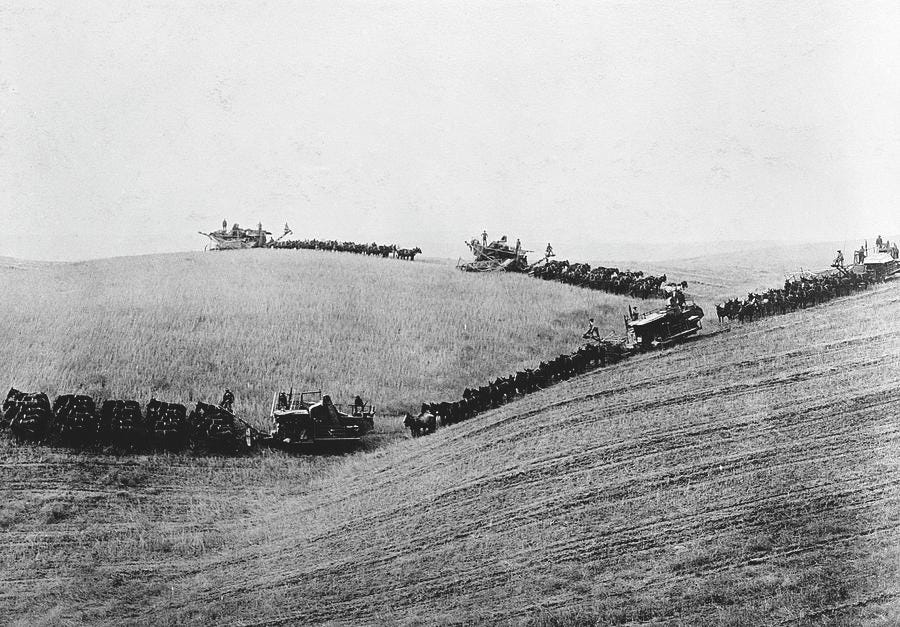

Horse-drawn plows had been around for centuries, but in the mid-19th Century Americans invented an entire suite of horse-drawn agricultural implements. These implements radically reduced the need for farm labor, particularly during the peak seasons when farm labor was most in demand. This enabled a family to run far larger farms than had previously been possible.

Eventually, all those horse-drawn farm implements were replaced by tractors powered by internal combustion engines, but hindsight should not cause us to diminish the importance of this 19th-century farming transformation. Equally important in enabling this transformation was the development of railroads, steamships, and refrigeration, which finally made intercontinental exports of perishable food viable.

The combination of all these technological innovations enabled farms to specialize in growing specific products for the market that were best suited for their natural environment and then export to growing cities around the world.

One of the key problems of agriculture is the unstable need for labor. While manufacturing and commercial activities typically have fairly stable labor demands over the course of a year, the need for agricultural labor varies greatly over the calendar. Agriculture demands a heavy workload during plowing and the harvest, while relatively little work is needed during the winter. The exact timing for plowing and harvesting varies depending on short-term weather patterns. Worse, all the local farms growing the same crops in a specific area have synchronized labor demand so they end up competing against each other for scarce labor.

This means that the farming calendar shifts wildly between too much labor and too little labor. When dealing with perishable food products, there is little room for flexibility. The solution is to mechanize the tasks that require large amounts of labor, while getting horses to do most of the work. And the rapidly-growing factories of the early Industrial Revolution were perfect for churning out those new labor-saving devices.

Some examples

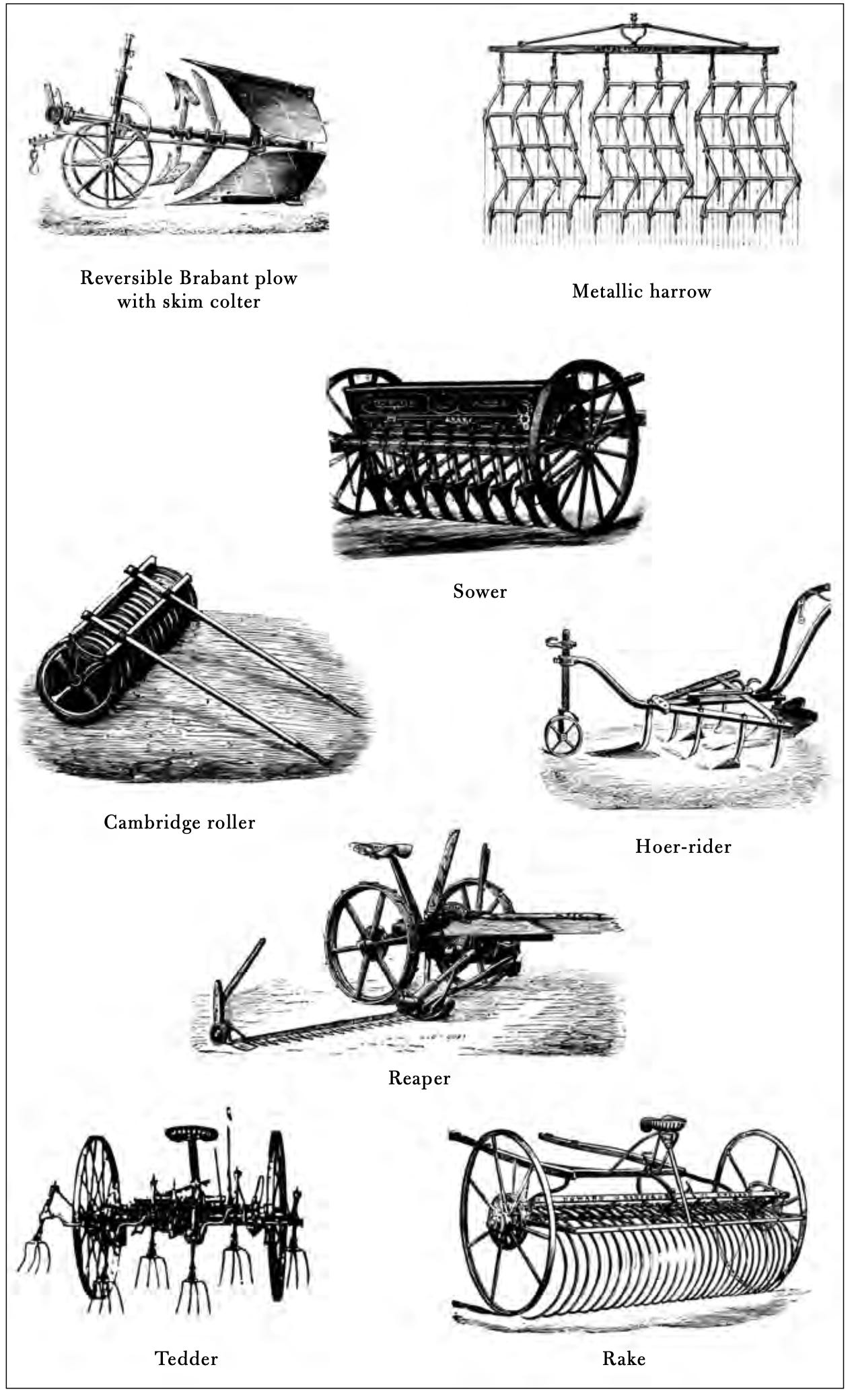

One of the most useful of the new farming devices was the Brabant plow (shown at top left of the graphic below). The Brabant plow was essentially two plows built together on one axle. One plow blade turns the soil to the left, while the other blade turns the soil to the right. This enabled farmers to run the plow in any direction under most conditions without wasting trips. It was also considerably shorter than previous plows, so it was much easier to turn after each pass (the hardest task in animal-drawn plowing).

This new-fangled plow had a flip mechanism to switch between blades and precise mechanisms for adjusting the incline, width, and depth of the plow. This enabled one person to guide the horse team while controlling the plow. Previous versions of plows required two persons on level ground and four persons on sloping ground. One person would drive the horse teams while the others would control the incline, depth, and width of the plow by hand (not an easy task).

The Brabant plow was what we would today call “point and click.”

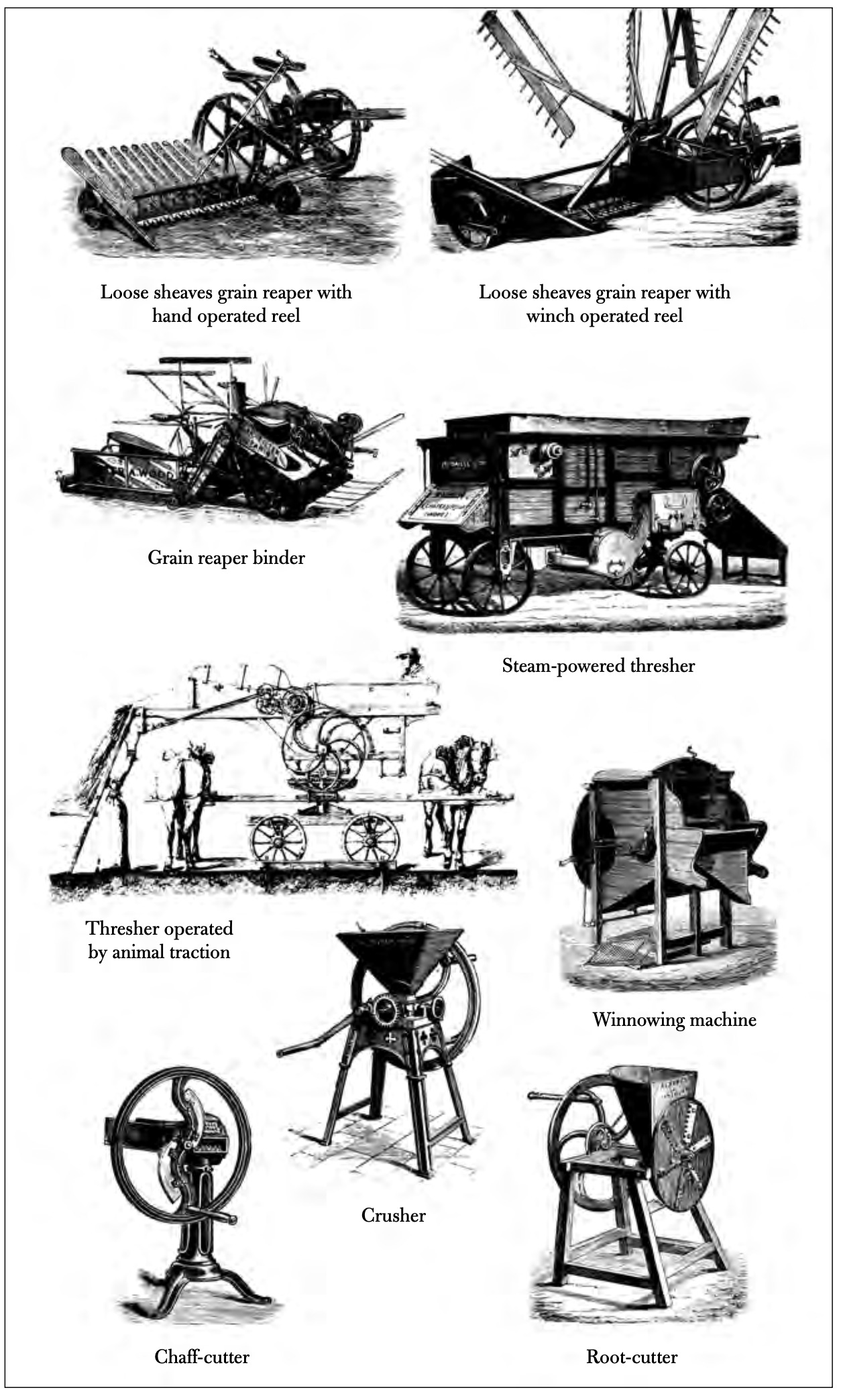

Another important innovation was the mechanized reaper (top left in the graphic below), which automated hay-making and harvesting. Mechanical reapers are approximately ten to twenty times more labor-efficient than the scythe, rake, and sickle. This impressive device was eventually replaced by a reaper binder, which also bound the cut grain into sheaves.

One of the worst jobs in grain farming is threshing (separating the seeds from the husks and straw). The seeds were then stored in a granary. Whether done by hand or by animal, the process took many days and typically resulted in significant damage to the seeds. The mechanical thresher dramatically speeded the process, lowered the need for manual labor, and reduced crop damage.

Powering the threshers progressed from hand cranks to draft animals and then finally steam engines. After threshing came the bevy of hand-cranked sorters, winnowing machines, chaff-cutters, root-cutters, and grinders that you can see at bottom in the following graphic.

One point that is often missed is that the automation of all the steps in the harvest also reduces the chances of spoilage. Farmers have a very limited amount of time to go through all the steps necessary to store the grain in the granary. If a strong rain or hail comes during any time in the harvesting process, the entire year’s crops might be ruined. And even under the best conditions, there were plenty of insects, birds, and rodents who were more than happy to consume part of the harvest.

During the harvest, speed was of the essence.

By the late 19th Century virtually every step in grain farming (and many other types of agriculture) had been mechanized. And it is important to realize that all of this occurred before the application of steam engines and internal combustion engine powered tractors. Virtually all of these devices were powered by horse, mule, or hand cranks.

Food exports

Almost all of these innovations were pioneered in the United States. Gradually those innovations diffused to the arable regions of Canada, Australia, and Argentina. Wherever these technologies were adopted, they led to massive increases in agricultural productivity and international grain exports.

Adoption in Europe, which was still was dominated by the Medieval farming system, was quite slow. Large farms in Britain, the Netherlands, and Prussia tended to be early adopters. In most parts of Northern Europe, however, these new agricultural technologies did not become dominant until just after World War II!

This does not mean, however, that these agricultural innovations did not affect the European continent. Far from it.

The concurrent transportation innovations of the railroad, steamships, refrigeration, and propellers enabled a dramatic increase in European food imports. Between 1850 and 1900, US grain exports to Europe grew from 5 million bushels to 200 million (40 times!) and prices fell by over 50%! Given that food made up a substantial portion of the budget for commoners in the 19th Century and much of this was spent on grains, this resulted in a substantial increase in material standard of living for the laboring classes.

Wool exports grew almost as fast. After 1875 refrigeration technologies enabled a similar growth in export of frozen meat from North America, Australia, and Argentina.

Regional Specialization

Massive grain and meat exports from North America, Australia and Argentina enabled (and indeed forced) Northwest European farmers to specialize to a far greater degree than in previous eras. Now no longer required to grow grain for their family and local cities and unable to compete against low-priced imports, each region specialized in the agricultural biproduct that grew best in their natural environment:

Agricultural regions near large cities specialized in perishable farm goods, such as milk, fruits, and vegetables.

Mountainous regions specialized in livestock and wool.

Coastal regions and river valleys with relatively warm climates specialized in wines and other alcoholic beverages

Denmark and the Netherlands specialized in dairy and pigs.

North Sea regions specialized in wool, flax, or hemp.

As with previous agricultural transformations (listed at the top of this article), this mechanization left Mediterranean Europe, Eastern Europe, and virtually all of the rest of the world almost untouched. Those regions still produced their food using virtually the same technologies and processes as their ancestors did for the last few thousand years.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

If you are interested in the intricacies of this and other farming systems, you can find a more detailed summary of A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in my online library of book summaries.

It’s difficult to comprehend all of the tiny improvements in knowledge that, accumulated over time, can lead to such a drastic improvement in food output.

We went from barely having enough to feed a few million people, to comfortably feeding 8 billion. There is room for improvement, but with current demographic trends, we may not ever need to feed more than 10 billion.

Great stuff. As always, so helpful to have factual information about how the world developed. Thank you!