In a previous articles, I argued that human material progress did not originate in the Industrial Revolution. I argued that it started much earlier in the Commercial societies of Northern Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and pre-industrial Britain. If you are skeptical of the above, I encourage you to read those posts first.

In today’s post, I ask the question:

Was the Industrial Revolution inevitable?

This article is one article in my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

Was the Industrial Revolution inevitable? (this article)

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Was The Industrial Revolution Inevitable?

Is modern progress an inevitable outcome given the human ability to innovate new technology? Is it just a matter of time? Do all the factors that I discuss in this book obscure a much simpler process?

These questions are important because they change the way that we view the origins of modern progress. If this were true, then it would seriously weaken my argument that the Five Keys to Progress and Commercial societies are critical concepts through which to understand modern progress.

In an influential article called “Was an Industrial Revolution Inevitable? Economic Growth Over the Very Long Run,” Charles Jones develops a simple mathematical model that he believes explains modern progress. It takes into account all the observations that I made earlier about innovations being the recombination of existing ideas or technologies. He shows that the nice curve predicted by his model closely resembles long-term economic growth. You can read a summary of Jones’ article in my library of online book summaries.

Jones’ model predicts long periods of very slow economic growth followed by a sudden surge. This sudden surge appears to “come out of nowhere,” but his model shows that it was just a continuation of the same process over long periods. And when we graph per capita GDP over long periods of time, that is exactly what we see:

As Jones sees it, this curve was the inevitable outcome of exponential growth in technological innovation caused by the recombination of simple technologies to make more complex and useful technologies. His interpretation is that the Industrial Revolution was inevitable given enough time.

So is Jones correct?

I love the model, but I disagree with the interpretation because it neglects other factors. Technological innovation is not the only factor in human progress. The rates of innovation are very sensitive to geographical conditions. Innovation requires food. Food is not inevitable. Babies consuming the food surplus played a major role in slowing technological innovation.

Nor does an increased population inevitably increase the rate of innovation. In traditional societies, very few people live in cities, typically around 3% of the population. Farmers create very few technological innovations outside the agricultural sector.

It is the cities where the action takes place. For this reason, the increase in the population of cities is far more important than the overall increase in population. And even among city dwellers, it is at most a third of the urban population who systematically develop the skills needed to innovate.

Innovation also requires that elites do not stifle the transfer of food surplus to cities where people of skills live. This makes the relative autonomy of trade-based cities essential to innovation.

In Agrarian regimes, elite expropriation drastically reduced the rate of technological innovation and the material benefits that went to the masses. Only Commercial cities were able to combine plow-based agriculture and reduce elite expropriation. Both were essential to technological innovation.

Nor is there a simple relationship between the size of the urban population and the number of skills. Small cities have a relatively low diversity of skills even if they are autonomous and trade-based. The bigger the city, the greater the diversity of skills. Based on what we know about networks, it seems likely that this relationship is also exponential.

Plus it matters which skills a city has. In any one time period after the evolution of Commercial societies, there was a very small number of cities on the leading edge of technological innovation. Those cities were Venice, Bruges, Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London in temporal order.

These cities combined the technologies, skills, and organizations that were most relevant to the newest innovations and the ones that had the biggest impact on societies. Due to what economists call “agglomeration” effects, entrepreneurs, artisans, skilled workers, organizations, and capital are all concentrated in this one city. New York City, Chicago, Detroit, and Silicon Valley played similar roles in later eras.

Charles Jones’ model also does not account for the fact that human societies can be very different from each other in the amount of technology and the rate of innovation despite its members being from the same species. As we already saw, geographical constraints placed much harder limits on some societies than others. As those societies gradually innovated technologies and approached their geographical limits, those societies diverged radically from each other in the level of wealth.

It was only when a society acquired the Five Keys to Progress that crossing the threshold to modern progress became possible. Geography, demographics, limited food, energy, and politics all placed very real constraints on both the rate of innovation and the degree to which innovation could lead to benefits for the masses.

Without Commercial societies, which invented the first four Keys to Progress and the existence of fossil fuels, the Industrial Revolution would not have been possible. And given how many Commercial city/states were conquered by Agrarian regimes that stifled their progress, it is entirely possible that all Commercial societies could have been wiped off planet Earth.

During the Commercial era, these cities were highly vulnerable to military invasion. Antwerp’s economy was forever disrupted by the brutal occupation by the Spanish in 1576. Amsterdam’s economy suffered similar, though less fatal, disruption from the French invasion of 1672 and later wars with Britain. London’s economy might also have been seriously interrupted if the Spanish Invasion of 1588 had ended differently. The Normans in Southern Italy as well as the Spanish, Austrian, and French empires conquered many other smaller, but promising Commercial city/states.

Because the Commercial societies emerged in very specific geographical and political conditions that were unique to Northwest Europe, it is safe to assume that their destruction would have forever eliminated the possibility of the Industrial Revolution.

So, no, I do not believe that the Industrial Revolution was inevitable. The Industrial Revolution required all Five Keys to Progress to come together at one time and place. The place was Northwest Europe and the time was between 1200 and 1850. The story could have worked out very differently.

All of the above does not mean that I do not find Jones’s conceptual model useful. I agree that progress and economic growth are based on exponential growth caused by recombination that starts slow and gradually picks up speed. We just have to be aware that it is a conceptual model that must be placed within the proper historical context.

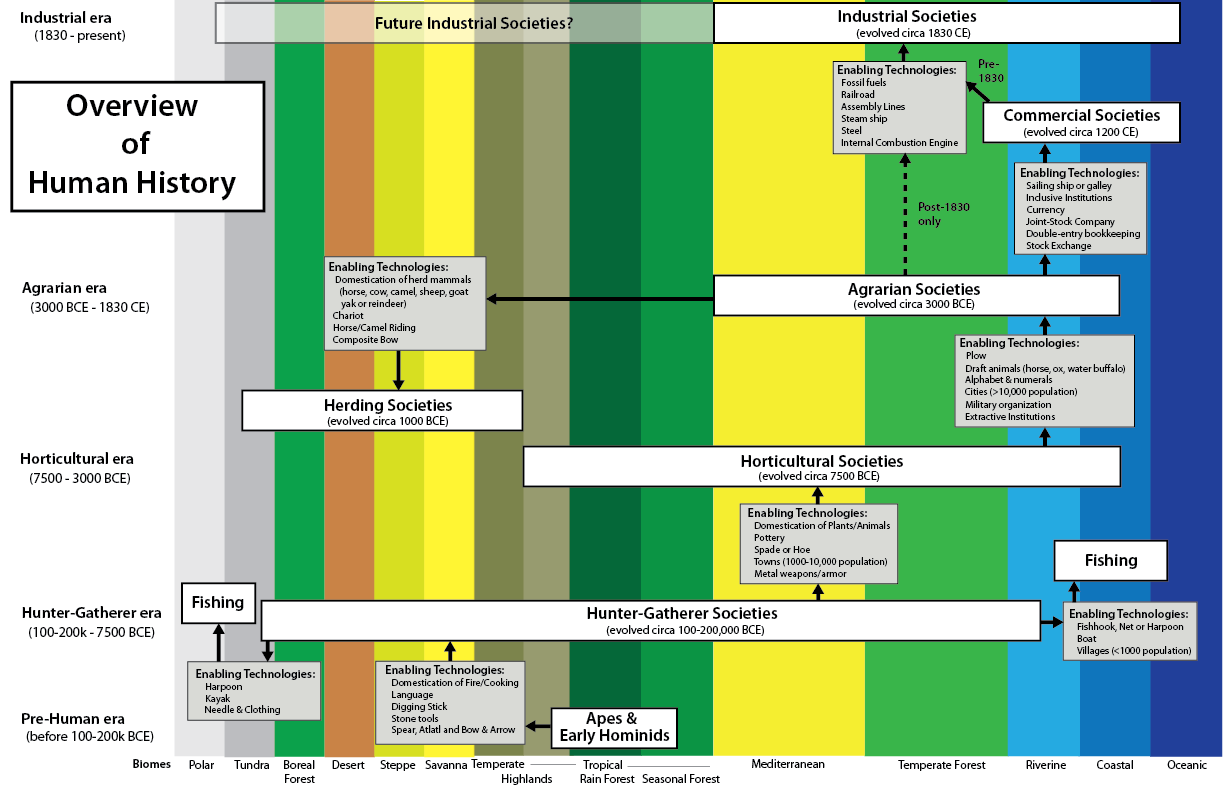

Take a look at this graphic. It is my attempt to explain human material history in one graphic. It combines the concepts of society types, biomes, and key enabling technologies. If you are interested in more details on this graphic, see my post All of human history in one graphic.

Take a look at the right middle where the white “Agrarian societies” block displays. Agrarian societies are a type of society that acquires the majority of its calories from plow-based agriculture. Agrarian societies dominated Eurasian and later the world from 3000 BCE - 1830 CE. That is a stretch close to 5000 years!

With very few exceptions, all nations in history that have industrialized so far had a long period as an Agrarian society. If dozens or perhaps hundreds of Agrarian societies persisted for 5000 years without experiencing an Industrial Revolution, there must be some kind of a barrier that makes it impossible or at least very difficult for it to happen.

I just have a hard time believing that the thousands of Agrarian societies that existed for 5000 years could not have randomly created the secret formula for industrialization if it were possible for them to have done so. I believe that the reason is that an Agrarian society cannot acquire all the Five Keys to Progress (which I believe are the fundamental preconditions for a society to transform from a state of poverty to progress):

A highly efficient food production and distribution system. This enables societies to overcome geographical constraints to food production so that large numbers of people can focus on solving problems other than getting enough food to eat.

Trade-based cities packed with a large number of free citizens possessing a wide variety of skills. These people innovate new technologies, skills, and social organizations and copy the innovations made by others.

Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. It is of particular importance that elites are forced into transparent, non-violent competition that undermines their ability to forcibly extract wealth from the masses. This also allows citizens to freely choose among institutions based upon how much they have to offer to each individual and society in general.

At least one high-value-added industry that exports to the rest of the world. This injects wealth into the city or region, accelerates economic growth and creates markets for smaller local industries and services.

Widespread use of fossil fuels. The incredible energy density of fossil fuels injects vast amounts of useful energy into society enabling it to solve a wide variety of problems. Without this energy, life would return to the daily struggle for survival that dominated most of human history.

Before about 1800, the fifth key to progress (widespread use of fossil fuels) was only acquired in Britain. This meant that an Agrarian society could either:

Remain in poverty for the overwhelming majority of its citizens, or

Acquire the first four Keys to Progress and transition into a Commercial society.

Totally collapse

The elites who dominated Agrarian societies were perfectly fine with the first state, while the second pathway fundamentally threatened their power. Elites are fine with increased agricultural productivity as long as the food surplus goes to them and not to farmers or cities outside their control. And since elites are rarely directly involved in growing their own food, they would not know how to make agriculture more productive. From their perspective, productive agriculture would just be a happy accident.

Decentralization of power (the third Key) would take away their wealth and power, while trade-based cities (the second Key) and export industries (the fourth Key) created rival elites that might challenge their power. In order words, Agrarian elites would rather have status and power within a poor society than have less status and power within a wealthy society. Modern authoritarian regimes typically make the same choice.

This is zero-sum thinking, and it is far more common than most affluent Westerners realize. When elites see the success of someone else as coming at your expense, this puts up a fundamental roadblock toward long-term economic prosperity.

Finally, I seriously doubt any Agrarian elites could even conceive of an economic transformation like the Industrial Revolution. Even Adam Smith in the 1770s had no idea that it would happen in his own nation. Perhaps if a king had known that he would have been able to get tanks, jet fighters, or flamethrowers out of the bargain, he would have given a thumbs up, but obviously, he could not even conceive of these future technologies.

Put simply, in Agrarian societies elites get to decide and they have no incentive to make their society richer if it threatens their status and power. For this reason, I do not believe that Agrarian societies could have industrialized without another nation showing them how to do it. Britain was that nation.

But when Britain industrialized, this changed everything for the rest of the world. The Industrial technologies invented by Britain:

Gave societies the ability to overcome geographical constraints that had kept them trapped in poverty for millennia.

Gave the leaders of those societies the incentive to do so.

Because many of those Industrial technologies could be applied to military uses, they gave elites with Agrarian societies a huge incentive to promote their use. Initially they tried to copy military technologies, skills, and organizations while minimizing social and political change, but they found out the hard way that this could not be done.

This article is one article in my multi-part series on How progress spread across the globe:

How Progress Spread Across the Globe (podcast)

Was the Industrial Revolution inevitable? (this article)

I tend to agree with you here. I don't think the industrial revolution was inevitable, but rather just the right factors and conditions coming together at just the right time.

Asking this question though is a bit like asking where the “Great Filter” is, in terms of Fermis paradox.

Good discussion. Have you read this piece (or related arguments): https://acoup.blog/2022/08/26/collections-why-no-roman-industrial-revolution/

You sort of touch on this in your point about Britain and fossil fuels, though not directly. I'm curious if you generally agree with this logic or not. The idea being that it's actually very hard to imagine a useful steam engine being invented for any purpose besides pumping water out of large coal mines, in a society that has very large demand for coal for basic heating because wood isn't available in sufficient quantity, and coal is. So even in a society with a culture of commercial invention, if there's not a practical use-case for a highly inefficient initial steam engine, maybe the technology never goes anywhere.

This at least raises the question, if the island of Great Britain lacked significant coal deposits and the economic history of Europe were otherwise largely unchanged, how much later might the Industrial Revolution have happened? Perhaps other Commercial parts of Europe would have eventually deforested to the point that they made more use of coal and went down the path of building ever-better steam engines. Or perhaps not.

Devereaux's argument at least makes me wonder to what degree timberland per capita really differs from place to place within the core countries of NW Europe circa 1700, and what the rate of change was.