How and why Commercial Societies created material progress

And why they did so long before the Industrial Revolution

In my book series and this Substack article, I have made the claim that:

While the Industrial Revolution was a critical breakthrough in human material progress, it was not the beginning of progress (as most economic historians believe)

Commercial societies invented human material progress long before the Industrial Revolution

Commercial societies were a necessary transition stage between agricultural societies and modern Industrial societies

Neglecting the critical role of Commercial societies undermines our understanding of the causes of human material progress.

In this article, I want to explain why and how Commercial societies invented human material progress. While I do not go so far as to say that material progress was inevitable in all Commercial societies, it seems very likely at the least.

What is a Commercial society?

Just so we are clear on definitions, I define Commercial society as a type of society that:

The majority of its food calories are purchased from the marketplace. Most people produce a good or service to earn the money to buy food produced by others. This is very different from all previous types of society where the vast majority of people produced their own food directly.

Lacks widespread use of fossil fuels, which is a defining characteristic of the Industrial societies that we live in today.

Famous examples of Commercial societies include the:

Many (most?) of the city/states of Ancient Greece

Medieval city/states of Northern Italy (Venice, Florence, Genoa, Milan, and many more)

Late Medieval city/states of Flanders (Ghent, Bruges, Ypres, and Antwerp in modern-day Belgium)

The Dutch Republic (1579-1795)

Pre-industrial England, particularly in the southeast (roughly 1500-1800)

The following is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Read more articles about Commercial societies:

Innovation and Progress in Commercial Societies

Commercial societies had many similarities to the modern societies of today. They were based upon large, autonomous trade-based cities with large numbers of artisans, traders, merchants and bankers. The majority of the citizens acquired their food by purchasing it in the market. Many of those citizens were highly skilled in emergent technologies of their day (what we would now call “cutting-edge” technology). Commercial societies had very high levels of urbanization and their citizens were highly literate.

Because of those characteristics, Commercial societies were extraordinarily innovative. They made important innovations in agriculture, energy, transportation, industry, finance, education, military, urban services, politics, science, art, diplomacy, and many other fields. Indeed, it is hard to think of a domain in which Commercial societies did not make important contributions.

With their dense concentrations of free citizens with widely varying skills, Commercial societies were technology aggregators. Commercial societies copied the best technologies, skills, and social organizations from other commercial societies. Then they recombined those innovations in new ways to create even more technologies, skills, and social organizations.

Each city tended to focus its resources on a few potentially profitable industries and innovate in those areas. This built the foundation for export industries. Then other cities could copy those innovations and modify them for different purposes.

Copying other societies came naturally to Commercial societies. Their day-to-day workings naturally promoted frequent contact between trading ships, traveling merchants, skilled craftsmen, and ship crews. Many Commercial societies had large numbers of skilled immigrants who brought new ideas and skills to their adopted homeland.

Commercial societies naturally increased the productivity of agriculture (the first Key to Progress). Because the citizens of Commercial societies purchased their food in the market, this gave a strong incentive for local farmers to increase their food production and specialize.

At first this impact was only in a small hinterland within walking distance of the city, but it gradually spread outward. The more the population of the city grew, the more local farmers were drawn into producing for the market. As more and more farmers were drawn into the market, the productivity of agriculture gradually increased until it far surpassed neighboring Agrarian societies.

Because commercial transactions required a certain amount of trust in strangers, Commercial societies tended to have much higher levels of trust than Agrarian societies. This helped them adopt a positive-sum mentality where strangers can cooperate to the benefit of both parties. This was a distinct change from the zero-sum mentality that dominated Agrarian societies.

Commercial societies had a strong incentive to innovate and copy new transportation and communication technologies. Being linked to each other via galleys and later sailing ships, each city could copy what worked best from all other cities, leading to far higher levels of innovation than in the surrounding Agrarian societies. As more and more Commercial societies evolved and their total population grew, innovation slowly accelerated.

Each Commercial society acquired technologies, skills, and social organizations from the other Commercial societies. This ensured that the process of innovation was additive. Breakthroughs were never lost, and the useful ones were always built upon.

With each generation the population of Commercial cities grew larger and larger, accelerating the recombination of old ideas to form new ideas. This ensured that innovation and progress were constantly accelerating.

Perhaps the most important innovation of Commercial societies was inclusive institutions. While centralized extractive institutions dominated Agrarian societies, elected mayors and town councils ran Commercial societies. Local militia filled with free citizens defended the cities from invaders. Guilds competed with each other for economic gain and political power. Many cities had a variety of religious institutions competing with each other for worshipers.

Most importantly, each of the Commercial cities competed against each other. Even if a small group of merchants or guilds could control one city, they could not control all Commercial cities. Any centralized institution that undermined innovation would cause the city to decline and another city to rise up to take its place.

It was this decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power (the third Key to Progress) that enabled progress to get started in Commercial societies. Success was no longer about climbing up to the top of centralized monopolies. It was now necessary to out-innovate the competition.

As Commercial societies grew in number as well as population, their people grew richer. As they grew richer, its people could afford to pay others to solve their problems. At first the problems were about basic survival, but gradually they shifted to paying for a higher quality of life. As merchants, artisans and other skilled workers competed with each other to offer solutions in the marketplace, progress began to take hold.

Commercial societies found ways to increase cooperation to solve common problems. Cooperation in previous societies was largely based upon reproduction, self-defense and food production. Commercial societies added cooperation within the marketplace to solve virtually any problem that others were willing to pay money for.

By the 16th Century, Commercial societies were surging away from the rest of the world in the complexity of their technologies, skills, and social organizations. More importantly, they were starting to produce real progress that changed a person’s standard of living within one lifetime. Progress had evolved.

Indeed, between 1200 and the Industrial Revolution these societies accounted for the bulk of the innovation and all of the progress, making Europe by far the most innovative continent during this period. Without these Commercial societies, however, Europe would have been little different from Asian Agrarian societies in their rate of innovation.

Economic Growth in Commercial Societies

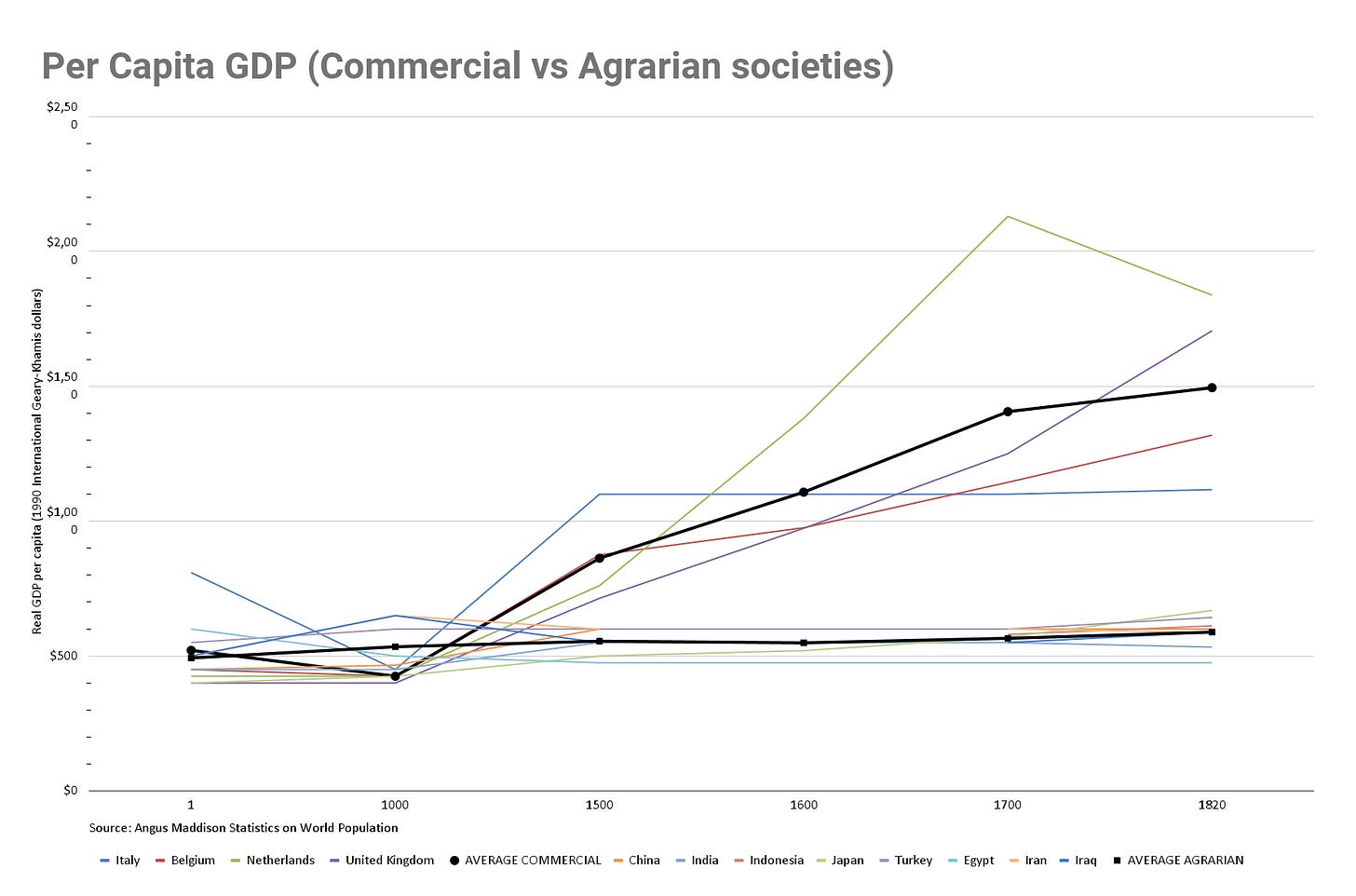

All of these innovations led to the strongest economic growth the world had seen up to that time. Estimating the wealth of societies that existed centuries ago is not easy. Fortunately, Angus Maddison has created his extremely useful database with estimates of per capita GDP for past societies. His figures are, of course, just estimates. At least for now, however, they are by far the best method for determining the wealth of past societies.

When we use Maddison’s estimates of historical per capita GDP, it is clear that Commercial societies experienced a different growth trajectory from other societies. In the year 1000, all complex societies in Eurasia had a per capita GDP between $400 and $650/year (i.e. at or just above subsistence levels).

It seems likely that this is roughly the same standard of living that humans experienced for all of history before that year. There is no evidence that any society reached a higher level before 1000, except in a few Imperial capitals that acquired their wealth by extracting it from other regions, which would have had little to no impact on the median standard of living. Progress was something humans of that era and previous eras could simply not comprehend.

By 1500 things were beginning to change. While all the Asian Agrarian societies were stuck at subsistence levels, the European Commercial societies experienced an upturn in per capita GDP. This is likely the first sustained increase in economic growth in world history.

More importantly, Italy jumped up to $1,100/year. This was a 144% improvement over its levels in 1000. And since Northern Italy was certainly more prosperous than Southern Italy, the actual level of economic development of the Northern Italian city/states was certainly much higher than $1100/year. One can also see a noticeable upturn in Flanders (in present-day Belgium) from $425 to $875/year.

After 1500, we see an upturn in both the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom went from $714/year in 1500 to $974/year in 1600. This made the United Kingdom the third richest society in the world at the time. And since Southeast England had a higher standard of living than Scotland, Ireland and the rest of England, levels in Southeast England were certainly even higher.

After 1500, both the Italian and the Flemish economies failed to keep up. Italy experienced almost no economic growth in the next 320 years, while the Flemish economy grew at the rate of the rest of Europe. The military occupations of the Spanish, French and Austrian empires took a huge toll on both societies.

The best evidence of progress, however, was in the Netherlands, which grew from $761/year in 1500 to $1,381/year in 1600. This was probably the fastest sustained economic growth up to that time, and it firmly established the Netherlands as the richest society in the world.

Dutch economic growth continued through most of the 17th Century, reaching a level of $2,130/year in 1700. That is the highest per capita GDP that any nation would reach before the Industrial Revolution.

And given that detailed economic analyses conclude that the Dutch economy peaked around 1670, this figure may understate the actual peak level. It is not a coincidence that 1670 marks the year when Agrarian France invaded the Dutch Republic and almost destroyed the regime. Once again we see evidence of invasion by Agrarian empires stifling much smaller Commercial societies.

After 1700 the United Kingdom and the Netherlands moved in opposite directions. The Netherlands declined in the 18th Century until it fell to $1,838/year in 1820. Some of this was undoubtedly due to the French occupation during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars and their trade blockades, but it is clear that the Dutch economy was in decline well before that time.

Meanwhile, the economy of the United Kingdom grew from $1.250/year in 1700 to $1,706/year in 1820, approaching the level of the Netherlands. It is important to note, however, that the British rate of growth during the 18th Century was almost identical to the rate of the 16th Century, overturning the commonly held belief that it was solely the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th Century that transformed Britain’s fortunes. Though cotton textile factories transformed parts of Northern England and Lowlands Scotland, their overall effect on the standard of living in the rest of Britain before 1830 was very small.

The above is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can purchase discounted copies of my book at my website, or pay full prize at Amazon.

Read more articles about Commercial societies:

"Produces the majority of its calories from people selling a product or skill, so one can buy food from the marketplace. This is very different from all previous types of society where the vast majority of people acquire their own food directly."

I love this definition, so clearly delineates an agrarian society from a commercial one.

The efflorescences of these merchant cities was pretty mild in terms of progress. Between 1500 and 1600 the average increase in income per day seems to be about a penny per year. I doubt anyone even noticed this rate of progress. In addition, since the mortality was worse in cities, I wonder if the wage rates were needed just to get people to come to the cities and die.

To me, progress is a wide scale, preferably global, phenomenon, and that doesn’t even begin to show up until we add fossil fuels and mechanization to the mix.