How the Ancient Egyptians tamed the Nile

And built the foundation for the world's longest civilization.

A key theme of this Substack column and my From Poverty to Progress book series is the importance of geography as a constraint on the history of human material progress. In a previous article, I explained how the geography of the Middle East made it very likely to be the first region to develop agriculture. This is just one example of where geography has played an important role in structuring the history of an entire region.

But good geographical preconditions are just the starting place. Humans still need to innovate the technologies, skills, and social organizations needed to achieve the first Key to Progress: A highly efficient food production and distribution system. This enables societies to overcome geographical constraints to food production so that large numbers of people can focus on solving problems other than getting enough food to eat.

This article explains how the Ancient Egyptians learned to turn the Nile River valley into a home for millions of human inhabitants. The food surplus they achieved was a key foundation for what is likely the world’s longest civilization.

Note: the following description and graphics were adapted from A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart. You can find a more detailed summary in my online library of book summaries.

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

The importance of rivers to civilizations

Before getting into the specifics of the Egyptian civilization on the Nile river, it is important to understand why rivers are important. It is not a coincidence that the vast majority of Agrarian civilizations were based on rivers, including the:

Tigris-Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq

Indus river in modern-day Pakistan

Yellow, Yangtze, and Pearl rivers in modern-day China.

Ganges river in modern-day India

Ganges-Brahmaputra-Megha river basins in present-day India and Bangladesh.

Irrawaddy River delta in present-day Burma.

Chao Phraya River delta in present-day Thailand.

Mekong River basin in present-day Cambodia and Vietnam.

Red River delta in present-day Vietnam.

While rivers are not essential for the development of complex Agrarian cities, they do make them far more likely. If a region has other geographical factors that promote the development of complex Agrarian societies and there is a major river within that area, a large city will likely evolve on its banks.

Rivers offer crucial advantages to human development; they:

Offer sources of (hopefully) clean drinking water.

Make it easier to remove human waste.

Offer sources of irrigation for crops.

Deposit additional nutrients in the soil for growing crops.

Enable cost-effective transportation of people and freight.

Offer defensible lines to block the approach of enemy armies.

While rivers are common in many regions, not all rivers are useful for Agrarian societies. In most cases, the river must be located in a biome that enables plow-based agriculture. In some cases, as in the Desert and Seasonal Tropical Forest biomes, rivers can effectively create little islands of agriculture within an otherwise hostile biome.

In addition to being located in a hospitable biome, to support complex societies, rivers must have all or almost all of the following characteristics; they must be:

Substantial in width, so that enough water is carried.

Navigable by large boats (to facilitate trade)

In flow all year-round, particularly near the mouth

Emptying into an ice-free ocean year-round

Free from large cataracts or waterfalls (except near their upstream source)

Free from large marshes near their mouth.

To fulfill all of these qualifications, a long section of the river must be located on gently sloping terrain, but not so gently sloping as to allow the formation of marshes. Many rivers do not have long stretches such as this, a key barrier to the development of complex Agrarian and Commercial societies.

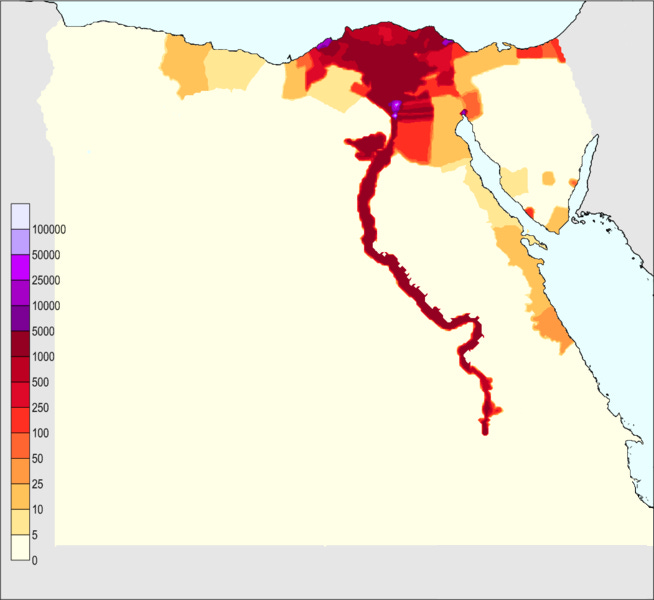

The Nile river fulfills all these requirements. As I am sure that you know, the Nile river is the longest river in the world. The Nile river is easily navigable year-round from Sudd wetlands in modern-day Sudan to its delta on the Mediterranean sea. Even better, the Mediterranean sea gives access to all other civilizations in the West and Middle East.

As best we know today, farmers started cultivating the Nile river valley about 8000 years ago.

The two sources of the Nile are in the highlands of Ethiopia (the Blue Nile) and the Lake Victoria region (the While Nile). Tropical showers in these rainy Tropical regions have nowhere else to go but northwards. In addition to vast amounts of water, both tributaries carry enormous amounts of sediment containing vital plant nutrients. Perhaps, most importantly, the Nile river floods twice per year (a very unusual characteristic), making it easy to have two distinct growing seasons.

With each flood, the water rose up about 9 vertical meters higher on the banks and covered almost all of the valley. Sediment from silt (essentially eroded Ethiopian dirt carried downstream) added about 1mm of fresh fertile soil each year. Each flood also built up the height of the banks on the edges of the valley.

The main problem is moving the water and storing it where the crops are. Since the Nile eroded its valley with relatively steep banks on the side. The trick was to move the water uphill, something that water just does not want to do. This called for skilled use of hydraulic engineering, an Egyptian specialty.

Hydraulic technologies

Most likely, it took very smart people hundreds of years to find out how best to do it, but fortunately, the Ancient Egyptians had two chances per year to improve, and it was not hard to get actionable feedback from each harvest. Any improvement in technologies could rapidly diffuse up and down the entire river valley.

Villages were typically higher up on the banks above the flood water line. Farmers then only had a short walk down the bank to their fields. Because the valley was long and narrow, every Egyptian farmer was a short walk from a reliable source of water.

Most likely, the first Egyptian farmers only worked fields that were immediately adjacent to the river. Perhaps some fields were watered with flood water that had been trapped by natural depressions year-round. Then the Egyptians learned to construct man-made basins and dykes.

Finally, some bright engineers came up with the idea of transforming the entire hillside to make them fertile. By building dikes at narrow places in the valley and a series of transverse canals, levees, and basins upstream of those dikes (see below), Egyptians could channel the flood waters up the hillside and then trap the flood waters in thousands of separate basins. They also constructed feeder canals to move the water into entirely different areas.

This final stage of sophisticated hydraulics probably did not arrive until after the Greek conquest in 333 BCE. Animal-traction plows likely were used at a later date.

The water could than be transported into individual fields when the farmers needed them using balancing poles (shadoufs), Archimedean water screws, and animal-driven water wheels. Each technology was relatively simple, but together they made up a sophisticated hydraulic system. Many of these technologies are so efficient that they are still in use today (see photos below).

Farming technologies

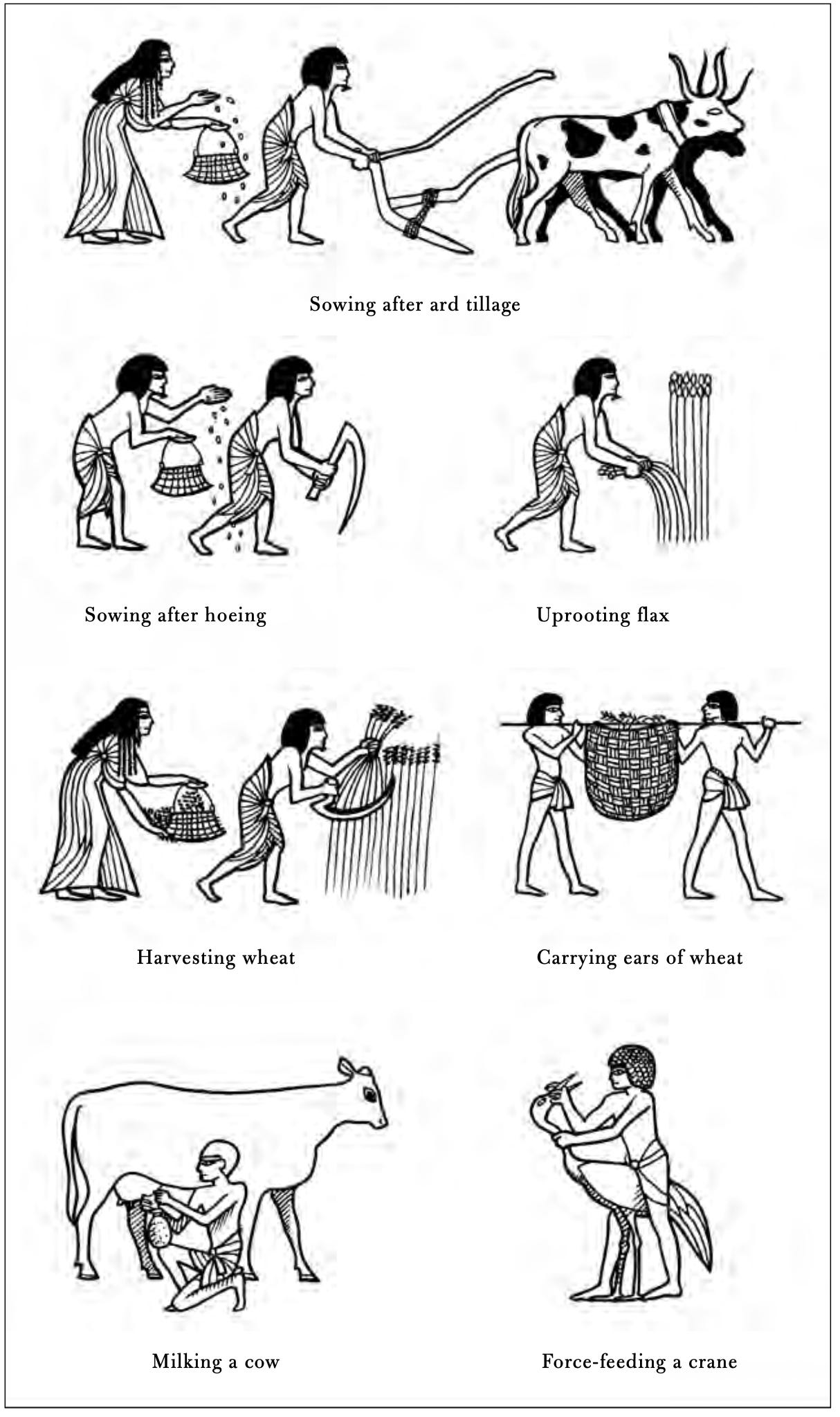

Of course, getting the water to the farmer’s field is only half the battle. The individual farmer’s family needs to go through an entire process of cultivating the field. Farming technologies played a critical role, particularly the ard plow (likely the first version of animal-driven plow).

In some ways, it is a misnomer to call the ard a plow, as it does not actually plow, i.e. turn over the soil. The scratch plow functions somewhat like an oversized digging stick that is dragged along the ground to create a long, shallow trench. The main purpose is to make it easier for farmers to later break up the soil using hand tools. The actual turning over of the soil was accomplished using spades and hoes.

The farming calendar

All agricultural societies are driven by a rigid calendar based on the biological needs of their staple crops. In the Nile river valley the key seasons were the:

The flood season (July-September)

The wet season where the soil was still wet and muddy from the previous flood.

The dry season where the water table declines enough for the soil to be dry unless irrigated (late winter and spring). This was the harvest time.

After decades of local experimentation, Ancient Egyptian farmers settled into a two-year cycle that rotated cereals (mainly wheat, millet and barley) with legumes. In addition, to being edible and nutritious, the roots of legumes contain Rhizobia bacteria that fix nitrogen from the air and replenishes this vital nutrient back into the soil. The Ancient Egyptians also grew flax, which is the raw material for weaving linen clothing and other textiles.

Each annual cycle was tied to the July-September flood from the Blue Nile, which was the biggest of the two floods. By staggering the crops among the local fields, each farming family had a relatively healthy diet and clothes to wear. Other necessary goods, such as tools, were likely imported from artisans living in other sections of the Nile.

Typically, farmers sowed their fields just after the flood waters receded when the soil was fully saturated with water and nutrient-bearing sediment. Because of the repeated flooding, the farmers only needed to leave their fields fallow for very short periods of time. The very short fallow seasons and double flooding made the Nile one of the most productive agricultural regions of the Ancient world (although far below modern productivity).

Food surpluses build empires

It was the surplus food from these harvests that built a civilization. Egyptian civilization started out as independent city-states. The larger and more powerful city/states conquered the smaller and weaker until just a few kingdoms were left. Then those large kingdoms consolidated into just two kingdoms: the Kingdom of the South and the Kingdom of the North. And then finally around 3150 BCE the entire Nile river valley was united into one kingdom. The first of the 30 (!) Pharaonic dynasties that lasted for 3000 years. Then stasis set in.

Did all this increase agricultural productivity?

Yes, the hydraulic farming system was far more productive than the preceding Slash-and-burn farming techniques that I covered in a previous article. Of course, all we can do now is estimate farming productivity, but it seems likely that the hydraulic farming system enabled a population density of 300 person per square kilometer. This is likely ten times denser than Slash-and-burn farming plus it allowed a permanent sedentary lifestyle. In Slash-and-burn farming, the entire village has to relocate to another area with the range every 3-5 years due to soil fertility depletion. Plus the hydraulic farming system could support farm more domesticated animals who could help with transportation and plowing.

So did this create material progress?

As regular readers of this column know, I use the following working definition of progress:

“the sustained improvement in the material standard of living of a large group of people over a long period of time.”

In particular, I focus on changes to the standard of living that are rapid enough and sustained enough that one person could notice positive changes within their lifetime. You can read more on why I believe this is the most useful definition of progress.

Despite the incredible amount of work and technological innovation in hydraulics, there is no evidence that this created an increased material standard of living for the masses. The reason is that agricultural productivity was only the first of the Five Keys to Progress. Each one of the keys is necessary, but not sufficient to produce material progress for the masses. In particular, Ancient Egypt was missing the Third Key: Decentralized political, economic, religious, and ideological power. Because of the increasingly centralized power, elites were able to extract the food surplus that farmers worked so hard for.

As with virtually all other agricultural societies, the increased agricultural productivity went to:

Having more babies

Taxes paid in the form of grain to elites

Given how dependent farmers were for water from the Nile and the impossibility of moving to the Desert, Egyptian elites had no problem extracting the food surplus from the hapless farmers. That food surplus could then be used to pay for the:

Pharoah

Pharoah’s priests

Pharoah’s judges

Pharoah’s bureaucracy (mainly scribes, who were the only men who could read and write)

Pharoah’s army

Construction of religious monuments

Construction and repair of the canals, dikes and basins

Lavish lifestyle of the elites listed above.

After about 670 BCE even this elite did not have real power. The Egyptians were conquered in turn by the:

Assyrians

Persians

Macedonians

Romans

Byzantines

Arabs

Mamluks

Ottomans

British

So what happened?

The history of Ancient Egypt is a lesson in the inadequacies of the Head Start theory of history. Those who embrace the Head Start theory believe that different levels of current economic development are determined by how much time has elapsed since that society:

developed agriculture or

formed a state (i.e. government)

Other than the Tigris-Euphrates, Ancient Egypt got a huge head start in agricultural, technological, political, and economic development. Ancient Egypt was a true superpower of the early Ancient world, but it failed to keep up.

By the Macedonian conquest in 333 BCE, it was clear that Ancient Egypt had fallen far behind the leading edge in all those domains. To give just one example, the Egyptian military fought largely with bronze weapons long after iron weapons had been adopted throughout the region.

Sadly, Egypt still has not caught up. Indigenous economic growth from 333 BCE to as recently as 1990 is almost completely absent. While the nation experienced some promising per capita growth between 1990 and 2012, it has been stagnant since.

It is hard not to come to a conclusion that the very same geographical conditions that gave the valley a head start eventually led to conservative complacency in the following millennia, particularly in military affairs. The lack of competition within the Nile river valley and relative military security due to its narrow connection to the rest of the Middle East meant that Egyptians saw no need to innovate until after it was too late. And then once the region was conquered by foreign power, its leaders benefitted more from cooperation with occupying armies rather than from domestic reform.

As far as I know, the only period when Egyptian leaders attempted to modernize was during the reign of Muhammad Ali (1805 to 1848). Ali implemented dramatic economic, military, and cultural reforms, but they ultimately failed to change much. By that time, Egypt had likely fallen so far behind the West that catch-up was not possible. Most likely the many factors that explain the relative stagnation of the Middle East (bottom of the linked article) also played important factors in Egypt.

Egypt still awaits its return to glory.

See more articles on Food and Agriculture:

Why agriculture is humanity's greatest technological innovation

Why Agrarian societies dominated recorded history for nearly 5000 years

If you are interested in this topic, you should read my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

If you are interested in the intricacies of this and other farming systems, you can find a more detailed summary of A History of World Agriculture by Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart in my online library of book summaries.

The GDP per capita chart shows Egypt keeping up with the growth rate of China from 1990 through 2010. Since that was a period of very rapid economic development for China, that seems fishy.

Also, I noticed a typo. You say that the Nile is the longer river of the Earth. Simply a typo.