How geography constrained development in Sub-Saharan Africa

And why is Africa still so poor?

A key theme of my Substack column and my book series is the impact of geography on human history. This article is part of an ongoing series that examines each of the regions on planet Earth to see whether their local geography enabled or constrained the evolution of complex human societies. Without complex human societies, material progress is not possible.

By complex societies, I mean:

Agrarian societies (who acquired their food calories from plow-based agriculture)

Commercial societies (who invented progress)

Industrial societies (which most of us live in today)

In this article, I will explain how geography constrained the material progress of Sub-Saharan Africa. The region has been a notorious laggard in material progress as measured by a large number of metrics, including economic growth, human development, freedom, slavery, poverty, agricultural production, literacy, diet, famines, sanitation, drinking water, life expectancy, neonatal mortality, disease, education, access to electricity, and housing.

Many theorists and political leaders have claimed this lack of economic development in Sub-Saharan Africa was caused by race, racism, colonialism, the Atlantic slave trade, or corruption. I believe that geography is the primary cause.

Much of this post is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Other articles about how geography has influenced economic development by region:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

How geography constrained progress (intro to this series)

Biomes

A biome is a category for a geographical area based on its dominant vegetation. The dominant vegetation in any area sets very broad constraints on what type of plants and animals can evolve there. The dominant vegetation sustains the local herbivores, which then sustain the local carnivores. Since humans use a portion of these plants and animals as base materials for food production, biomes play a critical role in constraining the types of human societies that can develop within them.

Plow-based agriculture, a necessary transition step to modern progress, is only possible at a distance from river basins in a few biomes:

Temperate Forest biomes

Mediterranean biomes

(after the invention of the steel plow in 1830s) Temperate Grassland biomes

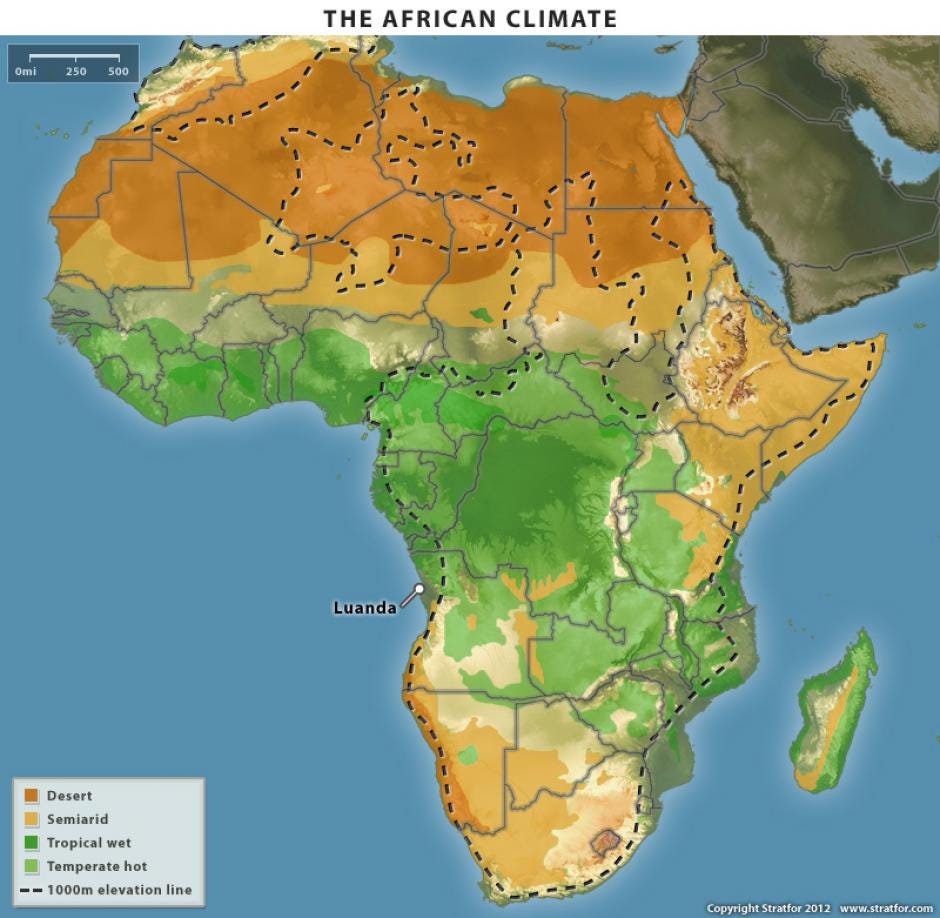

The biomes in Sub-Saharan Africa are not conducive to the evolution of complex societies. Africa is dominated by the Tropical Forest, Savanna, and Desert biomes.

In addition, the non-Forest ecoregions in Africa experience extremes in precipitation. Rain is almost entirely concentrated in the Rainy season, while the Dry season is close to Desert conditions.

The biome that is most conducive to development – the Temperate Forest – is completely missing from Sub-Saharan Africa. Only a very small Mediterranean ecoregion exists near the Cape in the extreme south. This ecoregion is too small to enable the evolution of complex societies.

Soil Types

Even with the proper biomes, a region needs fertile soil for agriculture. Because agriculture is key to feeding dense human populations, the type of soil in a region is critical to its ability to support complex societies.

Soil is the combination of:

weathered rock,

air,

water, and

organic matter from decomposing plants and animals.

The soil types in Sub-Saharan Africa are a little more conducive to plow-based agriculture than biomes.

About half of the land mass of Sub-Saharan Africa has soil that is not very productive. The soils of the Congo, East Africa and the Kalahari Desert are highly unproductive. There are, however, many regions with reasonably good soil. Inceptisol and Ultisols were fairly widely scattered throughout the region, plus the broad swath of productive Alfisol soil in the Sahel and Southeast Africa could have supported productive agriculture.

Altitude

Except for Highlands in Tropical latitudes, complex societies are concentrated on the plains at altitudes of 500 meters or lower. While landmass on Earth varies in altitude from just below sea level to 10,000 meters above, about 73.7 percent of humanity inhabits altitudes of less than 500 meters above sea level.

The bulk of Sub-Saharan Africa rests on an enormous plateau that is over 1000m in altitude. The edge of this enormous plateau is usually very close to the ocean, leaving little room for coastal plains. At the same time, there are few large mountains that can support a Tropical Highlands biome, the most advantageous biome in Tropical latitudes. The Tropical Highlands biome is largely restricted to Ethiopia and western South Africa.

Rivers

Most large and prosperous cities are located on rivers or natural ocean ports. Rivers offer crucial advantages to human development. Rivers:

Offer sources of (hopefully) clean drinking water.

Make it easier to remove human waste.

Offer sources of irrigation for crops.

Deposit additional nutrients in the soil for growing crops.

Enable cost-effective transportation of people and freight.

Offer defensible lines to block the approach of enemy armies.

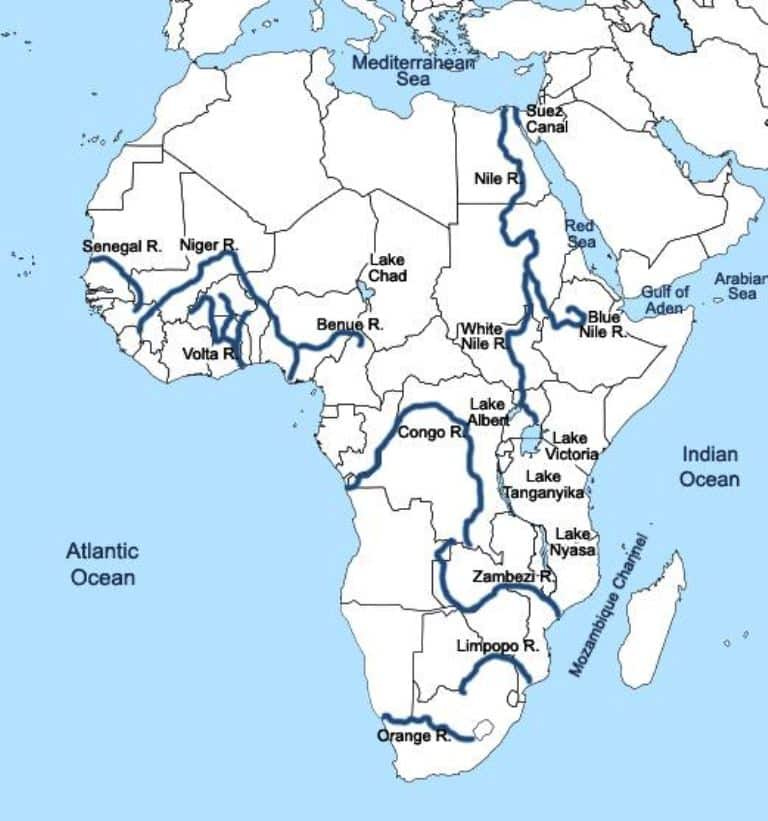

Sub-Saharan Africa has plenty of rivers. The problem is that the region does not have the right type of rivers. With the exception of the Nile river, most African rivers serve as barriers rather than as transportation corridors.

Rivers in Sub-Saharan Africa are hardly conducive to the evolution of complex societies. With few mountains tall enough to accumulate snowpack, little water is stored for the dry season. While the rainy season turns African rivers into torrents, the subsequent dry season turns those same rivers into a relative trickle.

This makes navigation by large boats difficult, if not impossible, in both seasons. In addition, the proximity of the African plateau to the coastlines means that large rivers tend to have large waterfalls and cataracts near their mouth. These waterfalls and cataracts create serious limitation to navigation between the ocean and the interior of the continent.

Nor does Sub-Saharan Africa have coastlines that could have supported port cities. The African coastline has very few peninsulas or islands, no major inland seas or protected waterways. And much of the continent is distant from the ocean. The combination of unnavigable rivers, great distances from the oceans and few good locations for ocean ports erected huge geographical barriers to African development.

Growing Season

Even if a region has a desirable biome, low altitude and agriculturally-productive soil types, other factors can preclude the development of productive agriculture. Even in areas that have all the necessary factors, some days are too hot; some days are too cold; some days have too much rain and other days have too little rain. One or two days of any of the above are not a problem, but if those days are strung together for weeks or months, agricultural production is seriously constrained.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any useful data on the Growing Seasons in Sub-Saharan Africa, so it is unclear whether this is a barrier to economic development.

Wild ancestors of domesticated animals and plants

Most of the factors that enable productive agriculture are pure geography, but biogeography also plays an important role. Productive agriculture requires domesticated animals and domesticated plants. In particular, a region needs:

Animals that are capable of pulling plows: horses, cows or water buffalo

Staple crops, such as rice, wheat, corn, or potatoes.

Before a society can domesticate a plant or animal, the wild ancestors of those plants and animals need to be either:

located in the region or

close enough that human migration can bring those animals into the region.

Sub-Saharan Africa did have some native wild ancestors of domesticable animals and plants. The Sahel region (just south of the Sahara desert) was a source of rice, millet, and sorghum, giving that part of the region a viable base of staple crops.

East Africa is known for its large herds of herbivores, but unfortunately, none of them were suitable for domestication. Cape Buffalo and Zebra are highly aggressive, so attaching them to a plow is extremely dangerous. Any historical attempts to do so likely ended in tragedy.

Though Sub-Saharan Africa did adopt cows, pigs, and sheep from the Nile river valley, horses were not used until very recently. And as we will see below, these animals were very vulnerable to the African disease environment.

The threat of Herding societies

As Peter Turchin has argued (summary here on my online library of book summaries), until the widespread use of firearms and cannons, the horse archers of the Eurasian steppe were the dominant military threat to Agrarian societies. Agrarian societies that were located near Temperate Grassland biomes in Eurasia with horse archers faced an existential threat. Combining rapid strategic and tactical mobility with standoff weapons in the form of the composite bow-and-arrow, the Herding societies of the steppe were dangerous enemies.

The regions within Sub-Saharan Africa that could support Herding societies were also a double-edged sword. Those Herding societies led raids on neighboring Horticultural societies. These Herding societies often conquered entire Horticultural societies and established themselves as the de facto ruling class.

One example that is very relevant today is in Rwanda, where the cattle-herding minority Tutsi dominated the majority of horticultural Hutus. Resentment about centuries of domination was a key ingredient in the genocide that some Hutus carried out against the Tutsi population in 1994.

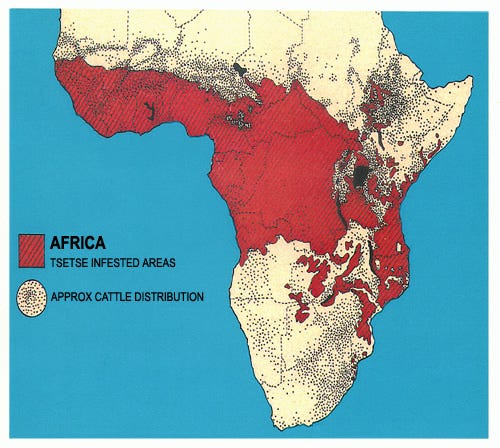

Disease environment

If that is not enough, Sub-Saharan Africa is an ideal climate for two scourges of humans and domesticated animals: malaria and sleeping sickness. Malaria was, and unfortunately still is, a mass killer of humanity. Even those that survive the deadly disease suffer recurring bouts that sap energy and make the victim unproductive.

In addition, sleeping sickness, carried by the tsetse fly, created vast regions where cattle and other herd animals could not live and other zones where they could only live seasonally. No other region on Earth has been so constrained by its disease environment.

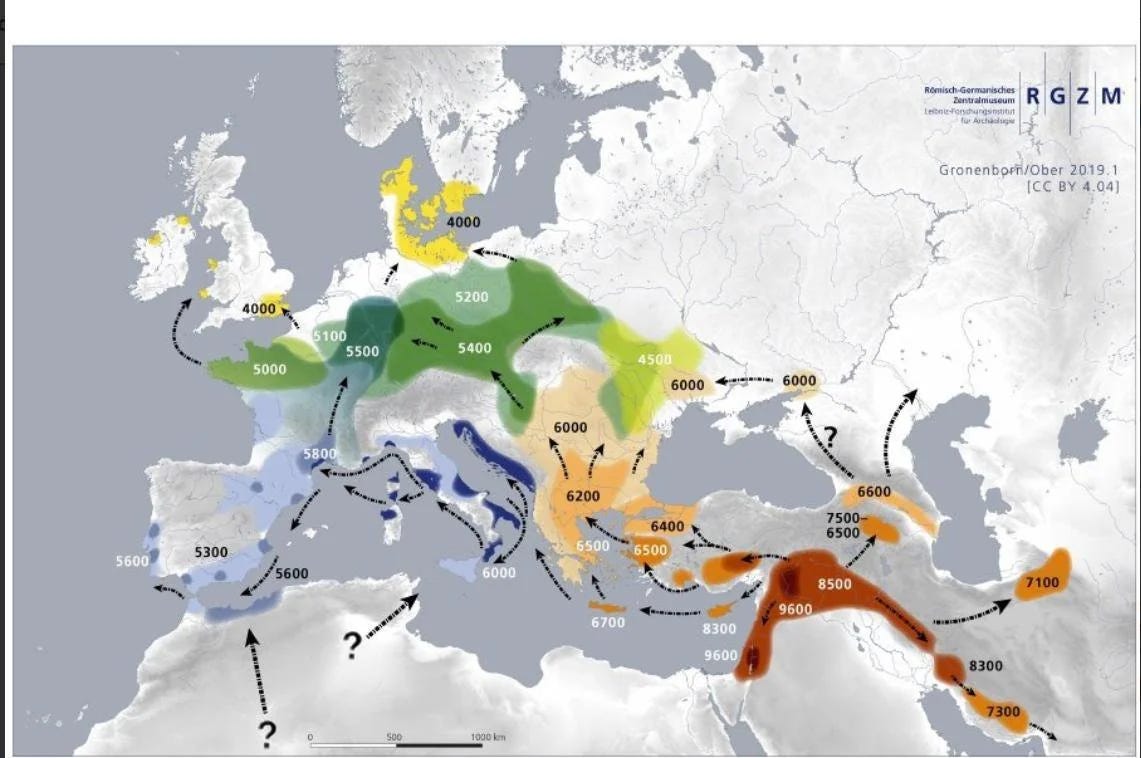

Geographical Isolation

The most important such constraint was proximity to the Middle East. As we have seen, agriculture evolved in the Fertile Crescent (modern-day Syria, Iraq, and Southern Turkey). Early Agrarian societies in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia played an important role early in the Agrarian era. These regions played a critical role because they had many wild ancestors of domesticated plants and animals.

Even though Sub-Saharan Africa is close to Eurasia, it is still relatively isolated. The Sahara Desert to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, and the Indian Ocean to the east each make it difficult for African societies to encounter and copy technologies, skills and social organizations from more complex Eurasian societies. Alone, these barriers would not have been insurmountable, but in conjunction with the other factors listed above, they hindered development in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion

All of these factors make it very unlikely that any complex Agrarian societies could ever have developed in Sub-Saharan Africa. While the Tropical Forest biome supported Horticultural societies and the Savanna supported Herding societies, more complex societies could not evolve. While Sub-Saharan Africa could support the Hunter-Gatherer, Fishing, Herding, and Horticultural sequences, it could not support the critical Agrarian sequence.

The biggest exception to this rule was the very small South African region of the Mediterranean biome with productive Alfisol soil. Because it was a small region with very different rainfall patterns (wet winters, but dry the rest of the year) and it lacked native wild ancestors of domesticable plants or animals, local Africans could not develop Horticultural or Agrarian societies in the area.

Before the arrival of the Dutch, the area that is now South Africa was dominated by tiny Khoisan Hunter-Gatherer and Fishing societies. The arrival of European settlers, who brought with them Agrarian technology, domesticated plants and animals enabled an explosive growth of Agrarian societies in this region.

For all of these reasons, I believe that geography is by far the most important factor in explaining why Sub-Saharan Africa has been very slow to develop compared to most other regions. Does this mean that Sub-Saharan Africa cannot experience material progress? No, in fact, over the last generation the region has improved substantially.

It is important to understand, however, that this material progress was only possible due to outside influence, particularly from Western Industrial nations. The Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom and the global trade system created by the United States made this possible. Industrial technologies, skills and social organizations enable people to overcome many, but not all, of the geographical constraints that previously undermined the possibility of progress.

For the first time, people anywhere on the globe had the opportunity to experience progress. They could now escape the trap of geographical constraints. Those that were successful in copying the UK experienced rapid and sustained economic growth.

In other words, the technologies invented by Britain in the Industrial Revolution and the global trade system were a cheat code that enabled most of the rest of the world to overcome geographical constraints that had limited their economic growth for millennia. Sub-Saharan Africa was just one region to take advantage of this phenomenon.

So what about the future? Geography still matters, particularly for land-locked African nations without easy access to container ports. But they are not the insurmountable barriers that they were for almost all of human history.

The extent of future African progress will largely be determined by the extent to which the region can:

Increase agricultural productivity (the first Key to Progress).

Gradually ratchet their economies up from low-value-added export industries to high-value-added industries (the fourth Key to Progress).

Much of this post is an excerpt from my book From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. You can order my e-books and audiobooks at a discounted price at my website, or you can purchase full-price ebooks, audiobooks, paperback, or hardcovers on Amazon.

Other books in my “From Poverty to Progress” book series:

Other articles about how geography has influenced economic development by region:

Why are there such huge variations in income across the globe?

How geography constrained progress (intro to this series)

Sub-Saharan Africa (this article)

Some other great Substack columns on geography that you should subscribe to:

You should read the paper "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development" by economists Acemoglu and Simon Johnson which argues against geography as a primary determinant of poverty in former colonies. Instead, it emphasizes the role of institutions over geographical factors. It's lengthy, but a great read. Also, check the paper "Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution" by the same authors and discusses the "reversal of fortune," where regions that were prosperous before colonization (such as parts of Latin America and India) are now poorer, while previously underdeveloped regions (such as North America and Australia) became wealthier. This reversal cannot be explained by geography because the geography of these regions did not change, but the institutions imposed by colonial powers did. The reversal is largely time-invariant.

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w8460/w8460.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiCn__2-Y2JAxVRWUEAHWr2IcEQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3DG6lAHqyG-5Xhv5VhYp0v

As far as domesticating animals, the Victorians were fairly successful in using Zebras to pull carriages.